The Changing Response to AIDS

A neglected global health crisis ultimately became a top priority for policymakers, donors, and doctors.

Last Updated

HIV/AIDS is one of the deadliest communicable diseases of the modern era: approximately thirty-three million people have perished from AIDS-related illnesses. The U.S. government and international organizations now commit significant resources to preventing and treating HIV/AIDS. However, this was not always the case. This timeline traces the evolution of patient activism, scientific research, international attitudes, and public policy that eventually converged to create the coordinated international HIV/AIDS effort that exists today.

1981

1981

- 1984

1981

- 1984

What Makes a Health Crisis?

Jun 5, 1981

What Makes a Health Crisis?

Jun 5, 1981

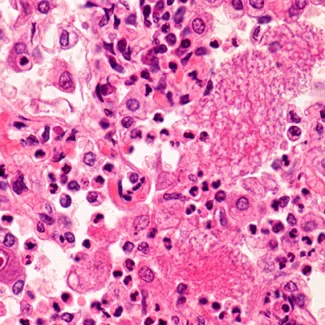

Five Men Die of a Simple Infection

Sep 24, 1982

Five Men Die of a Simple Infection

Sep 24, 1982

It’s Called AIDS

Jan 4, 1983

It’s Called AIDS

Jan 4, 1983

The Blood Supply Is Infected

Jun 1, 1983

The Blood Supply Is Infected

Jun 1, 1983

People With AIDS Adopt the Denver Principles

May 4, 1984

People With AIDS Adopt the Denver Principles

May 4, 1984

The Retrovirus Causing AIDS Is Isolated

Dec 17, 1984

The Retrovirus Causing AIDS Is Isolated

Dec 17, 1984

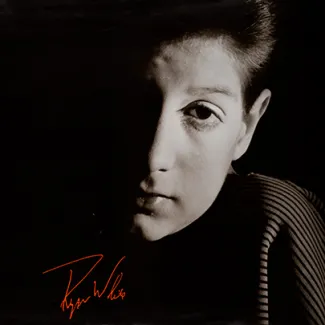

Ryan White Is Diagnosed With AIDS

1984

- 1984

Ryan White Is Diagnosed With AIDS

1984

- 1984

Thousands Are Dying

1985

- 1993

Thousands Are Dying

1985

- 1993

A Response Stirs

1986

- 1986

A Response Stirs

1986

- 1986

Uganda Starts an AIDS Control Program

1986

- 1986

Uganda Starts an AIDS Control Program

1986

- 1986

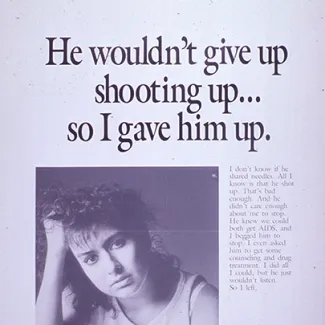

Blood Banks Start Testing the Blood Supply

1987

- 1987

Blood Banks Start Testing the Blood Supply

1987

- 1987

First Antiretroviral Treatment Is Approved by the FDA

1987

- 1987

First Antiretroviral Treatment Is Approved by the FDA

1987

- 1987

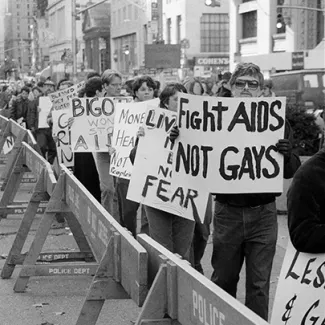

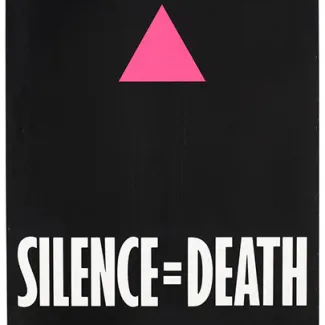

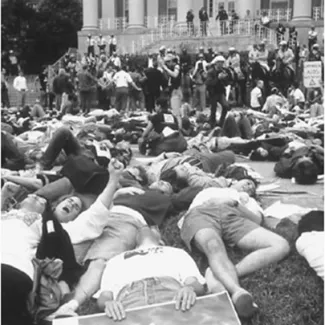

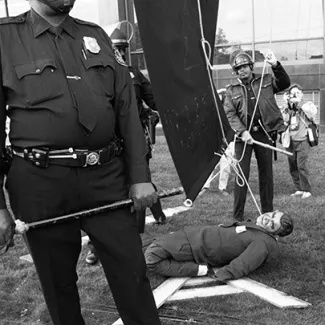

Activists Break Through Into the Mainstream

May 31, 1987

Activists Break Through Into the Mainstream

May 31, 1987

Reagan Acknowledges Crisis in a Dedicated Speech

1994

- 2016

Reagan Acknowledges Crisis in a Dedicated Speech

1994

- 2016

The World Works Together

1994

- 1994

The World Works Together

1994

- 1994

The Pandemic Peaks

Jan 1, 1996

The Pandemic Peaks

Jan 1, 1996

The Joint UN Program on HIV/AIDS Is Launched

1996

- 1996

The Joint UN Program on HIV/AIDS Is Launched

1996

- 1996

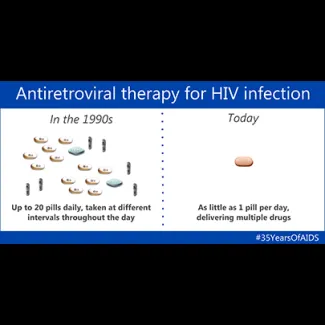

FDA Approves First Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy for Use in the United States

1997

- 1997

FDA Approves First Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy for Use in the United States

1997

- 1997

U.S. Companies Block Cheaper Drugs in South Africa

2001

- 2001

U.S. Companies Block Cheaper Drugs in South Africa

2001

- 2001

United Nations Declares Commitment to the AIDS Fight

2002

- 2002

United Nations Declares Commitment to the AIDS Fight

2002

- 2002

The Global Fund Starts

2003

- 2003

The Global Fund Starts

2003

- 2003

PEPFAR Is launched

2012

- 2012

PEPFAR Is launched

2012

- 2012

PrEP Is Approved

2021

PrEP Is Approved

2021

United Nations Introduces Plan to End the AIDS Epidemic by 2030

2023

United Nations Introduces Plan to End the AIDS Epidemic by 2030

2023

The Fight Against HIV/AIDS Is Not Over

The Fight Against HIV/AIDS Is Not Over

2023

Teaching Resources

Activity

Primary Source Analysis on the AIDS Epidemic

Length

15 Minutes to Varies