Modern History: The Americas

Although referred to as the “New World” by Europeans, the Americas have thousands of years of history.

After arriving some nineteen thousand years ago, the first inhabitants set up advanced civilizations with complex theologies and mature agricultural methods. After evolving relatively independently for millennia, the Americas’ isolation ended in the fifteenth century, when Spain and Portugal financed voyages across the Atlantic Ocean in search of trade routes, spices, and minerals. These two countries, along with Britain and France, split up the landmass and created lucrative colonies, devastating indigenous populations through warfare and disease: by 1600, the once-thriving population of the Americas was reduced by 90 percent. Governed by Europeans and bolstered by the slave labor of more than twelve million Africans, these colonies became the foundation for the modern countries of the region.

Enlightenment Values Inspire American Revolution

In the eighteenth century, a wave of new ideas was reshaping social and political life in Europe. Known as the Enlightenment, this intellectual movement promoted individual rights and freedoms. Its main concepts, such as liberty, equality, and the separation of church and state, still guide political systems today. As Europe’s empires expanded globally, these Enlightenment values spread overseas. In Britain’s thirteen American colonies, colonists who were frustrated by their lack of political representation used Enlightenment values to justify their declaration of independence and subsequent war against Britain. Following the American Revolution, these values would become enshrined in the U.S. Constitution, even though one of the central tenets—equality—was initially reserved for mostly landowning white men. Nevertheless, the U.S. Constitution and its Enlightenment values would serve as a model for future constitutions in countries like Australia and Mexico.

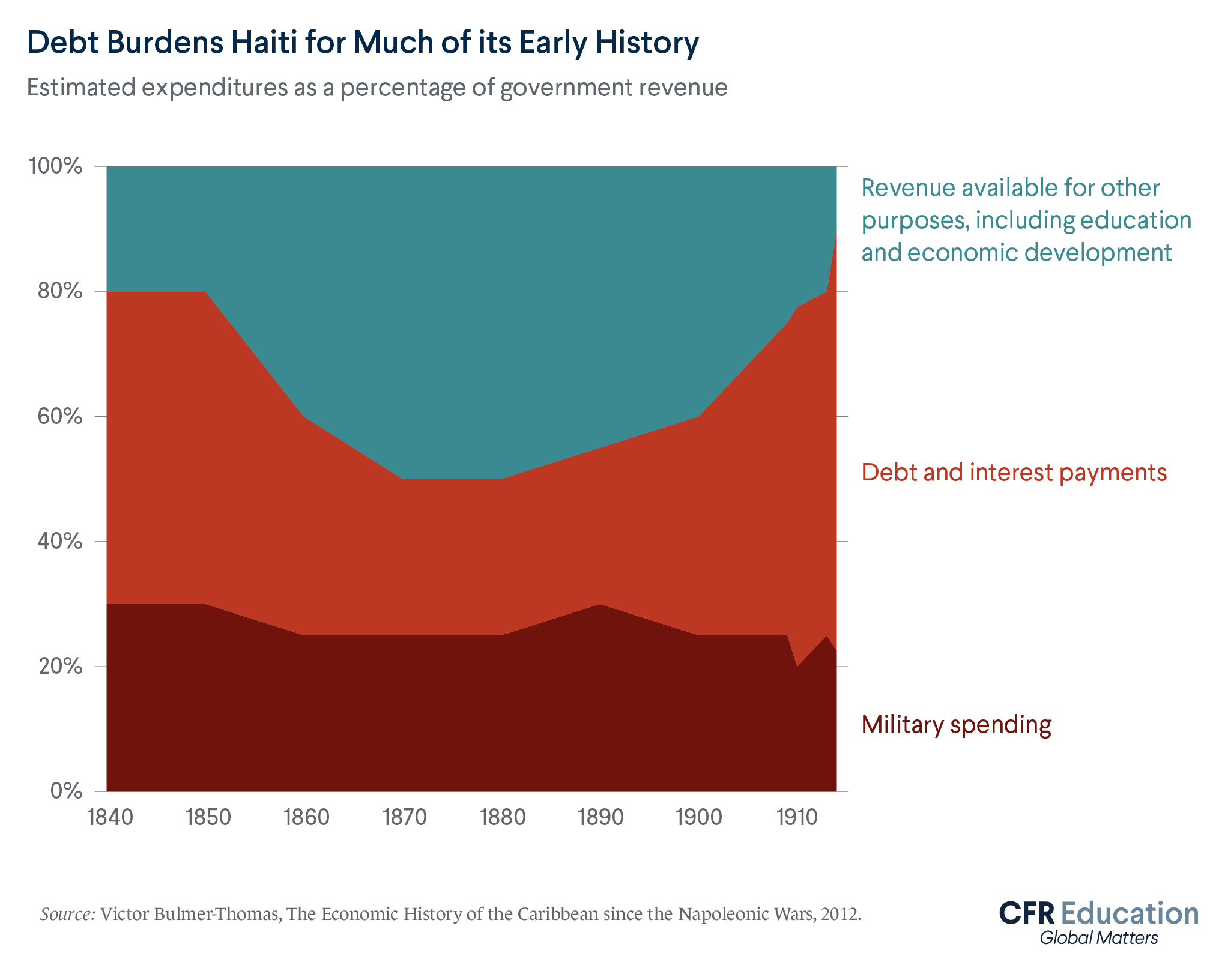

Haitians Defeat French Empire but Face International Isolation

Haiti was the French empire’s most profitable colony in the late eighteenth century. The small Caribbean territory—then known as Saint-Domingue—produced 40 percent of Europe’s sugar and 60 percent of its coffee, predominantly through slave labor. But in 1789, revolution upended France, as the people overthrew their monarchy in the name of liberty, equality, and fraternity. Two years later, hundreds of thousands of enslaved Haitians—who outnumbered slaveholders ten to one—began demanding these same Enlightenment-inspired rights. After a thirteen-year war, Haitians defeated the French and established the first Black-led republic in 1804. The European powers, however, did not immediately recognize Haiti as an independent country. Instead, Haiti was internationally isolated and made to pay reparations over the next 150 years to France for the loss of its colony—the equivalent of $20 billion today. This punishment bankrupted the once-prosperous colony, and Haiti today remains the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere.

Latin American Strongmen Replace European Colonizers After Independence

In Spanish and Portuguese colonies, political and economic privilege was tied to how much European ancestry one had, with the most power and property concentrated among the few who both claimed exclusively European heritage and were born in Spain or Portugal. Faced with these extreme systems of discrimination, Latin American revolutionaries overthrew their colonizers across Central and South America in the early nineteenth century. Leaders like Simón Bolívar—whose opposition to Spanish rule helped achieve independence for Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela—pledged to eliminate the colonial-era racial hierarchies. But in reality, independence rarely brought about equality or democracy. Rather, caudillos (“strongmen,” like Bolívar, who often led these independence movements) frequently perpetuated the same unequal, undemocratic systems that benefited the landowning elite. Instead of creating political systems that promoted equality among the region’s diverse groups, including Africans, Europeans, indigenous people, and those of mixed race, caudillos preserved hierarchies that favored the light-skinned and the wealthy—systems of power that shape Latin America to this day.

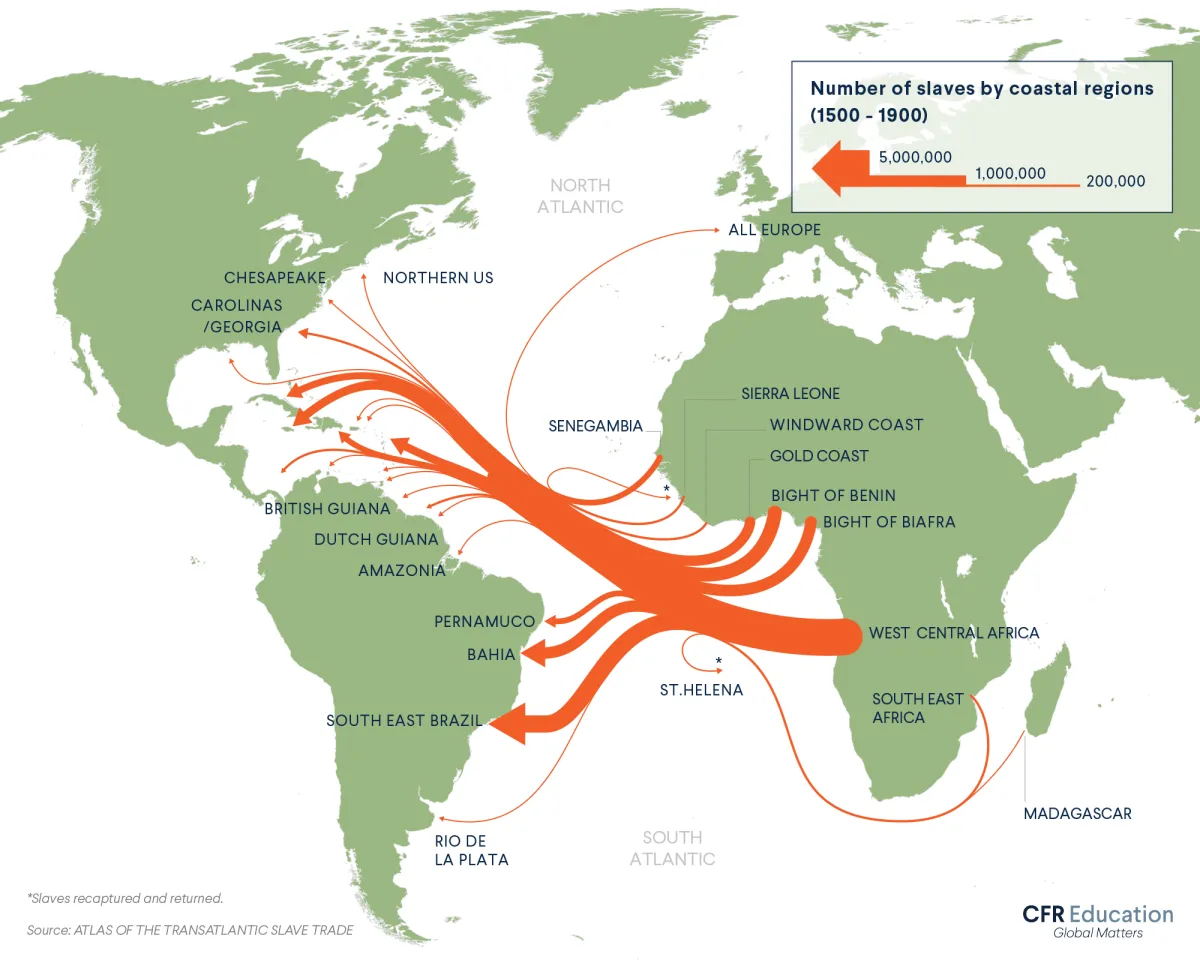

American Economies Built Through Slave Labor

Between 1503 and 1866, Europeans brought more than twelve million captured Africans to the Americas. European colonial powers relied on the profits from slave labor in their colonies to fund their military campaigns, expand their empires to other continents, and stay competitive as they vied for global trade dominance. Profits from slave labor also propped up the economies of the region’s newly independent countries. Enslaved people were sent to every part of the region, though three-quarters were sent to Brazil and the Caribbean. Enslaved people (including both Africans and indigenous people) performed backbreaking work on plantations that grew sugarcane and other cash crops and in mines that produced precious minerals like gold and silver for export to Europe. Their labor was integral to the region’s economies; in the United States, for example, the economic value that slaveholders placed on enslaved people exceeded that of all the country’s railroads and factories at the start of the American Civil War in 1861.

Americas Abolish Slavery, But Inequalities Persist

Slavery in the Americas lasted well into the nineteenth century. The practice was first ended in Haiti, in 1794. Soon thereafter, Simón Bolívar championed abolition while fighting for independence in South America. In 1833, the British abolished slavery throughout their empire, and three decades later the United States fought a civil war over the future of slavery; it was ultimately abolished with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. The last country in the Western hemisphere to abolish slavery, in 1888, was Brazil—the destination of nearly half of all enslaved Africans. Emancipation, however, did not mean equality. In the United States, discriminatory race-based laws replaced slavery, making it exceedingly difficult for African Americans to vote, buy property, and access equal education or medical care. In Brazil, formerly enslaved people were subjected to new systems of exploitative farming practices. In both countries, race-based inequality persists to this day; Brazilians and Americans of African descent earn just over half of what their white counterparts make.

Existing Communities Displaced as United States Expands

The United States quickly expanded across North America after gaining independence in 1776. At times, this expansion was peaceful: in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, the United States doubled in size after buying territory from the French, who had mostly given up their imperial ambitions in the region after their defeat in Haiti. But at other times this expansion came at the expense of local communities. For example, thousands were killed in the Trail of Tears, a U.S. government–led forced relocation of Cherokee people and other American Indian groups from their homes in the southeastern United States to Oklahoma. In 1846, the United States invaded Mexico, and—after winning a two-year war—seized territory stretching west of Texas to California. While white Americans were able to settle this land at little cost, the U.S. government often forcibly displaced Mexicans and American Indians.

United States Emerges a World Power From Spanish-American War

In the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution transformed the United States from an agrarian country to an industrial power. The invention of steamboats, the rise of manufacturing, and the construction of railroads drove prosperity and enabled U.S. expansion across North America. By 1898, the United States began to rise as an imperial power with global ambitions. In what became known as the Spanish-American War, the United States went to war with Spain in Cuba, seizing an opportunity to establish American dominance in the Caribbean and remove the last vestiges of the Spanish empire from the region. After just a few months of fighting, Spain agreed to leave Cuba, relinquish its other Caribbean colonies, and cede Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico to the United States. The victory cemented the United States’ status as a major world power, now with its first overseas territories. While Cuba and the Philippines eventually gained independence, Guam and Puerto Rico remain two of over a dozen U.S. territories. To this day, millions of people live in these two territories with American citizenship but with varying degrees of political rights and representation.

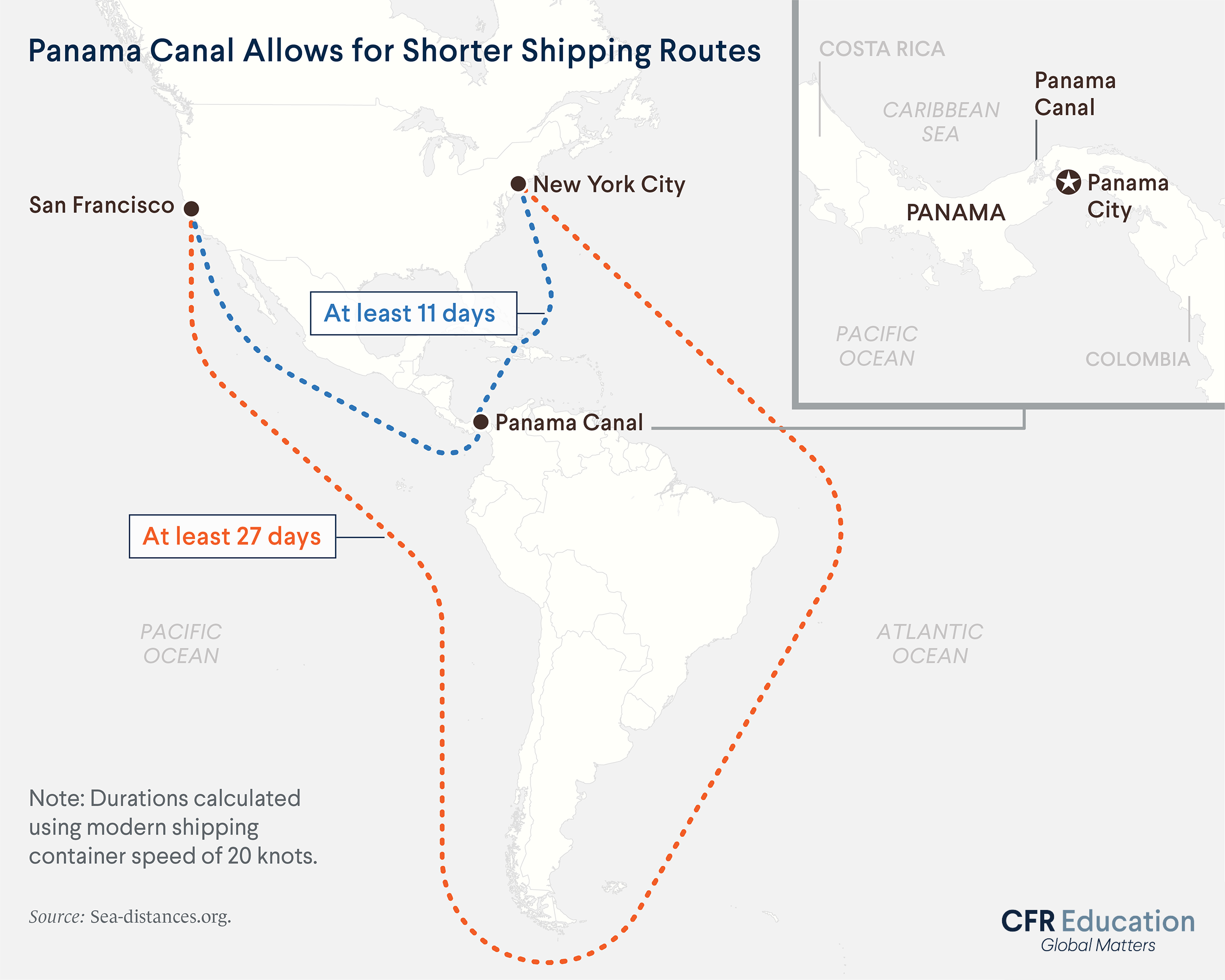

Panama Canal Transforms United States, Global Economy

In 1903, the United States sought to lease a piece of land from Colombia to build a canal joining the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. It would save ships from having to sail around South America and shave seven thousand miles off their journeys. The project was potentially so lucrative that, after Colombia rejected the U.S. proposal, the United States supported an armed insurrection in northern Colombia. That uprising gave rise to a new country, Panama, which quickly granted the United States control over the desired land. Construction of the forty-eight-mile canal was an engineering feat but also a highly dangerous process—one that the French abandoned just a decade earlier. Throughout the canal’s construction, twenty-seven thousand workers died, many from tropical diseases like malaria and yellow fever. When the Panama Canal opened to traffic in 1914, shipping costs dropped by 31 percent. The United States, meanwhile, gained access to new markets around the world and could now sail far more easily between its two shores, allowing the country to integrate its economy domestically and continue on its path toward becoming a global economic power. It was not until 1999 that the United States finally ceded control of the canal to Panama.

Latin America Stays Mostly Out of World War II

Sixteen million Americans and one million Canadians served in the European and Pacific theaters of World War II between 1939 and 1945. Most Latin American countries, however, stayed largely neutral, with only Brazil and Mexico sending troops to fight abroad. Why was Latin America mostly uninvolved in this conflict that consumed almost every region in the world? The Great Depression of the 1930s cratered the region’s economies, causing widespread political upheaval. Populist movements and military regimes swept to power in the resulting unrest, leading most countries to focus more on domestic, rather than international, affairs during this time. But that did not mean that the region was totally isolated from the war. Germany carried out espionage and propaganda campaigns to advance its political and economic interests in the region, and thousands of Nazis fled to Argentina and other Latin American countries after the war. Meanwhile, the United States worked with regional governments to deport Latin American citizens of Japanese descent to internment camps, where it had already forcibly relocated at least 110,000 U.S. citizens and residents of Japanese heritage.

Global Superpowers Intervene in Latin America During Cold War

After World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union—the world’s two superpowers—backed opposing capitalist and communist governments around the globe. In the Americas, the Soviet Union most famously allied with Cuba’s communist government, which rose to power in 1959 after ousting the country’s U.S.-backed dictator. Through its Cuban ally, the Soviet Union also supported communist groups elsewhere in the region, notably in Nicaragua. The United States was even more active in the region, largely due to its proximity, and advanced its political and economic interests by aiding anti-communist coups and supporting pro-American strongmen. But backing allied governments often came at a great cost for democracy and human rights. The Dwight D. Eisenhower administration, for example, backed a 1954 coup that toppled the democratically elected government in Guatemala, which gave way to a pro–United States authoritarian regime whose death squads would go on to kill thousands of civilians and political dissidents.

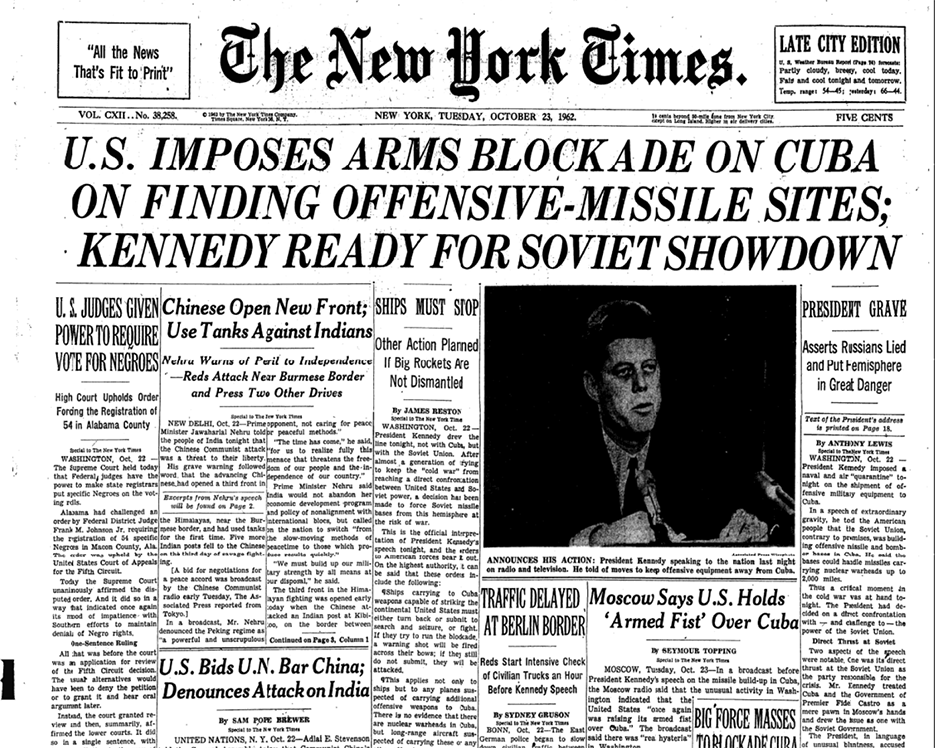

World Dodges Nuclear War With Cuban Missile Crisis

At the height of the Cold War in 1962, American intelligence discovered Soviet-built missile sites in Cuba. The Soviet Union insisted these were strictly to defend Cuba from American interference. The United States argued that Soviet nuclear weapons less than one hundred miles from U.S. soil posed a direct and immediate threat to American national security. President John F. Kennedy faced a difficult choice: invading Cuba could trigger a nuclear response, but inaction could allow further Soviet buildup on the island. Instead, President Kennedy ordered a naval quarantine of Cuba, which Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev considered an act of aggression. Just when nuclear exchange appeared imminent, Kennedy and Khrushchev reached a compromise: the Soviets would remove their missiles from Cuba in exchange for the United States secretly doing the same in Turkey and Italy and publicly promising not to invade Cuba. This thirteen-day standoff, known as the Cuban Missile Crisis, is potentially the closest the world has come to nuclear war.

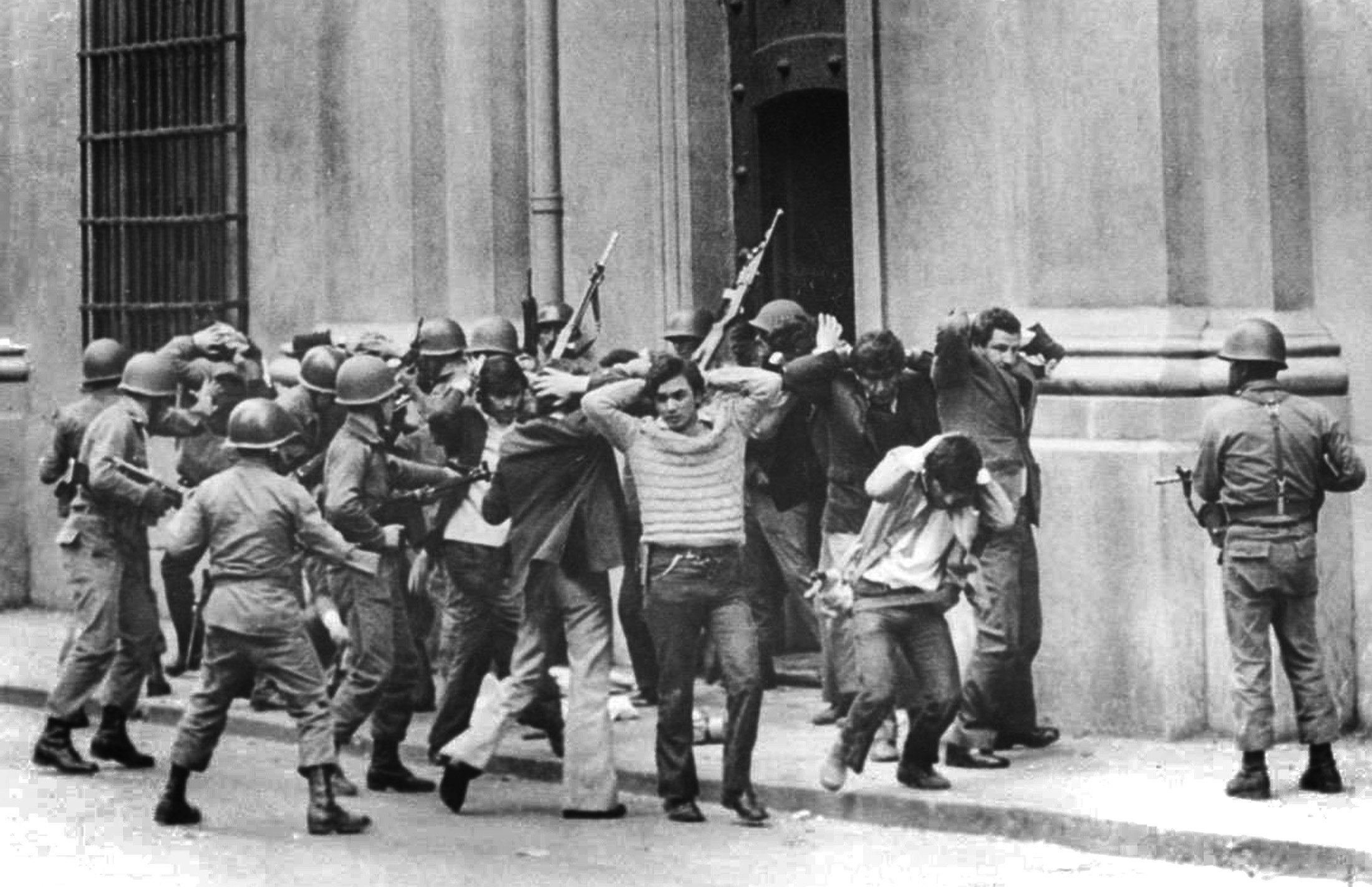

Decades of Dictatorships Terrorize Latin America

Anti-communist dictatorships controlled much of Latin America in the 1970s and 1980s, often committing extensive human rights abuses in order to remain in power. In Uruguay, the army killed hundreds of people accused of being Marxists or unionists and exiled five hundred thousand Uruguayans. In Argentina, the military regime (known as a junta) that came to power following a U.S.-backed coup killed or “disappeared” tens of thousands of people. The United States—particularly the CIA—provided training and support to at least half a dozen Latin American partner countries such as Chile and Paraguay through a program known as Operation Condor, even as these regimes tortured and killed thousands of leftists, students, union leaders, and other perceived political opponents. Although most Latin American countries have since democratized, the collective memory of this period hasn’t faded for many in the region.

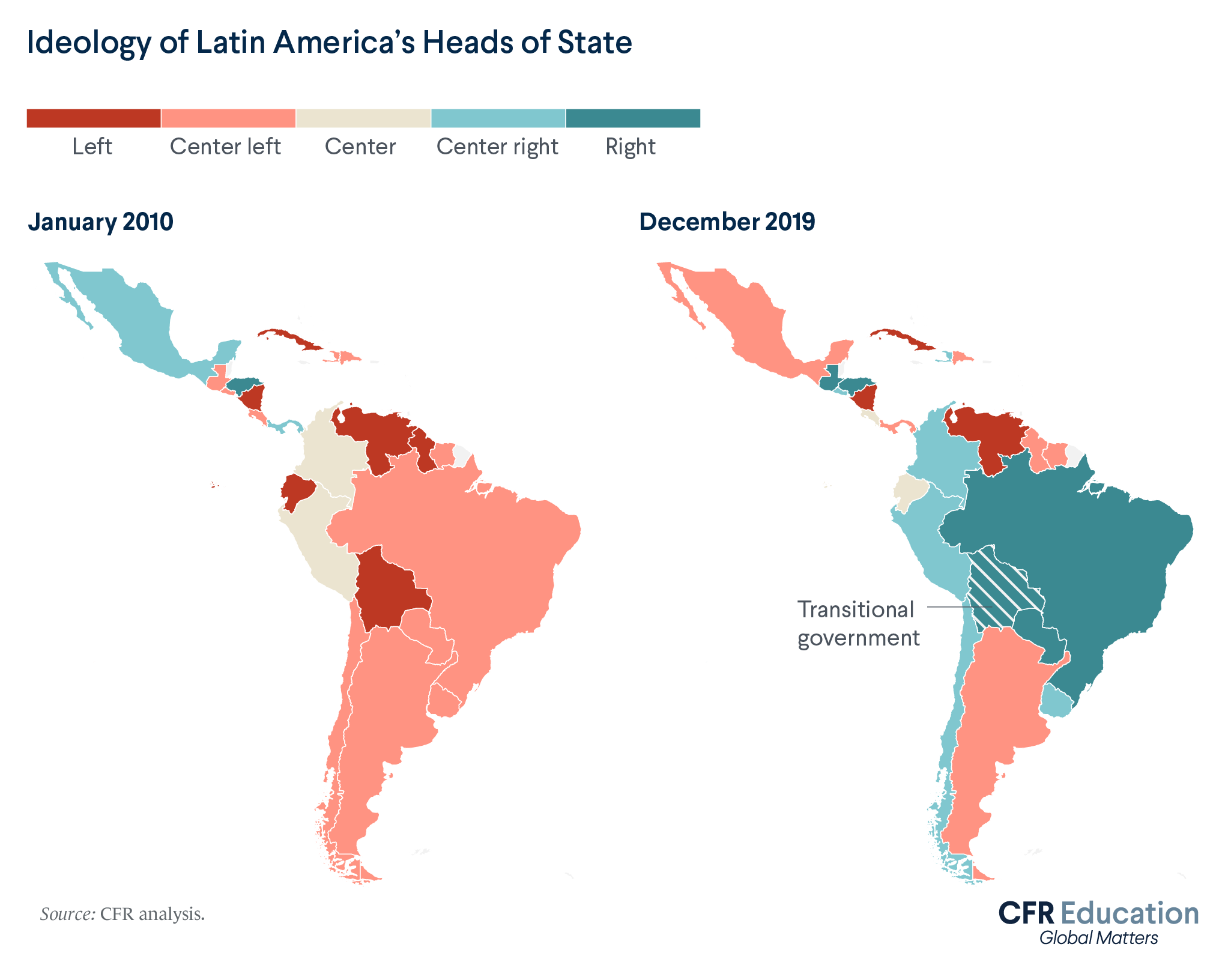

Hunger for Change Sparks “Pink Tide” Socialist Leaders

Recommendations from Western economists to cut public spending and privatize utilities under the Washington Consensus prompted backlash in Latin America. Citizens across the region took to the polls, electing socialist leaders who promised to restore public services and combat the region’s growing inequality in a wave known as the Pink Tide. Leaders like Venezuela’s President Hugo Chávez and Bolivia’s President Evo Morales reversed Washington Consensus reforms and made formerly private economic sectors state-owned. Others, like leaders of Argentina, Brazil, and Chile, focused on delivering social services while maintaining the Washington Consensus’s free market principles. But the pink tide was short-lived. A spike in global prices for resources like oil and metals helped governments spend more on social services, but price dips in the 2010s led to cuts. Soon Latin American countries were voting to change their political leadership. Today, most of Latin America’s largest countries—including Brazil and Chile—are run by conservative, capitalist leaders who have once again slashed social spending.