Why Do Taxes Matter?

What are the different types of taxes and how does a government's ability to collect tax revenue shape a country's economic and social development?

In 1789, Benjamin Franklin famously said only two things in this world are certain: death and taxes.

And, well, he wasn’t far off. Taxes are practically unavoidable.

For nearly every country in the world, taxes provide most of a government’s revenue. That funding pays for everything, including schools, hospitals, tanks, and roads. A government’s ability—or inability—to collect taxes can mean the difference between a thriving society with a robust social safety net and a country that struggles to provide for its citizens’ basic needs.

In this resource, we’ll break down different types of taxes, explore various approaches and challenges to tax collection, and consider how sound policymaking around this issue can support healthy and wealthy societies.

What are taxes?

Put simply, taxes are compulsory payments that governments impose; they are required by law.

They come in all different shapes and sizes. If you live in the United States, you’re likely accustomed to paying a little extra at the end of a meal (sales tax) or seeing some money disappear from your paycheck (income tax). The United States and many other countries also have special taxes for businesses, property, investments, and inheritances.

Tax revenue is critical for funding public services. In 2022, the U.S. federal government collected nearly $5 trillion in tax revenue, the bulk of which came from individual income taxes. State and local governments collect taxes to fund their operations too; New York’s state tax revenue totalled over $111 billion in 2022.

However, taxes do not exclusively exist to generate funds for government spending. Policymakers can also use them to influence people’s behaviors. For example, governments can impose “sin taxes” on things like gambling and buying cigarettes to disincentivize those activities. Conversely, countries can offer tax breaks to incentivize certain behavior, such as using green energy.

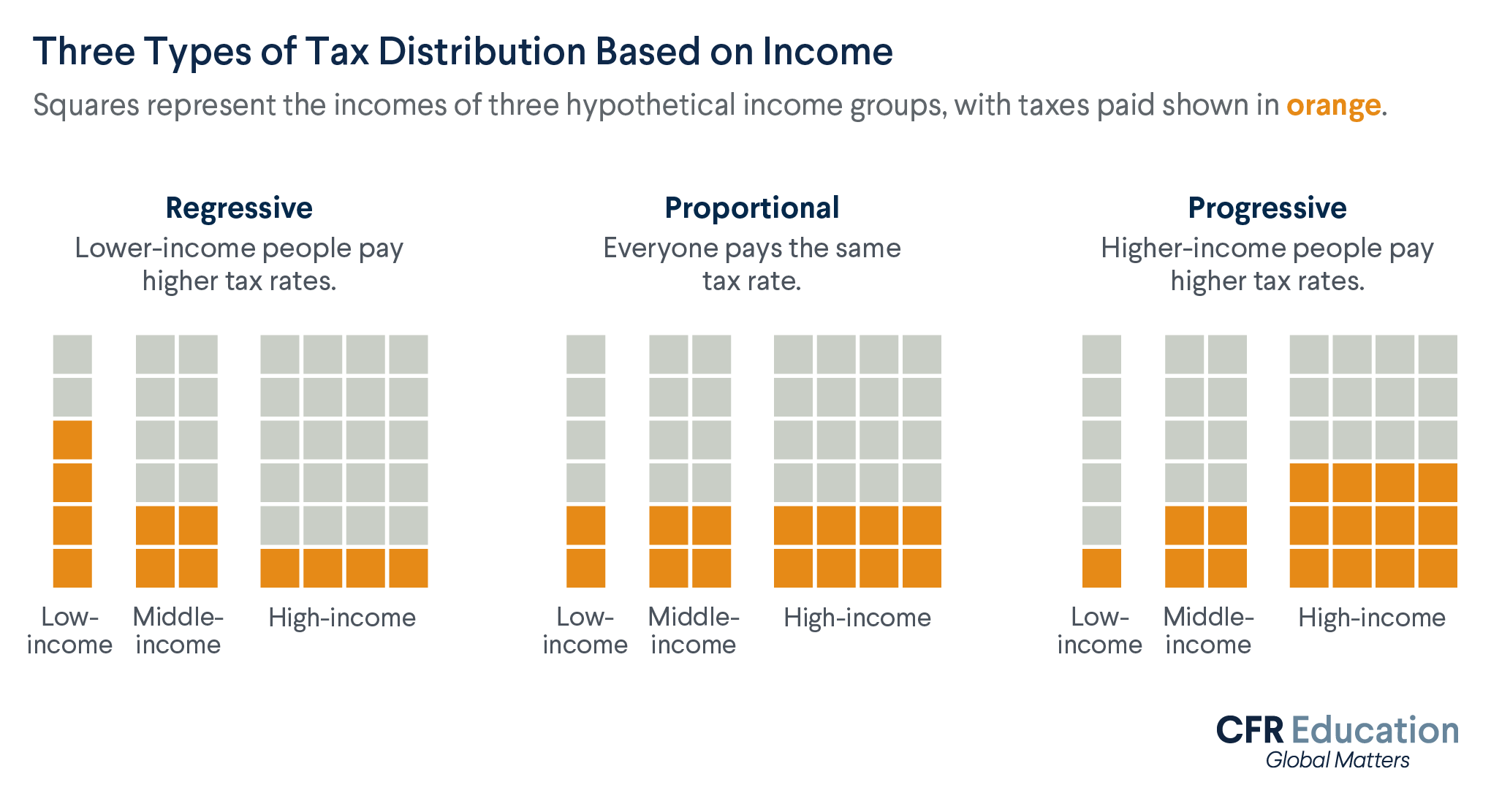

Taxes typically fall into one of three categories: regressive, proportional, and progressive.

Regressive taxes take a higher percentage of income from poorer people than wealthier people. Sales taxes are one example. Think of a tax on gasoline purchases: wealthy and poor drivers pay the same amount in taxes when filling up their cars; however, that dollar amount constitutes a larger percentage of the poorer driver’s income. Since regressive taxes place a heavier burden on the poor, some U.S. states do not impose sales taxes on necessities like food.

Proportional taxes do not take an equal dollar amount but rather an equal percentage of income from all people. A proportional (or flat) income tax would mean that a person making fifty thousand dollars and another making five hundred thousand dollars would both pay, say, 20 percent in taxes. Proportional-tax proponents argue that this method is fair, especially because high-income earners still provide the bulk of government revenue.

Progressive taxes take a higher percentage of income from wealthier people than poorer people. In theoretical a progressive income-tax system, the bottom 50 percent of earners could pay just a 5 percent rate whereas the top 1 percent of earners could pay a 45 percent rate. Progressive-tax proponents argue that each additional dollar of income is relatively less valuable as earnings increase. For example, an extra 5 percent of income for a poorer family that struggles to pay the bills is likely far more significant than an extra 5 percent of income for a wealthy family that lives a much more comfortable life. Some critics, however, claim that overly progressive tax systems can disincentivize work if wealthier people continuously have to pay higher tax rates.

The U.S. tax system is progressive, but it has become less so in recent years. In 1963, the top tax bracket for Americans was over 90 percent. In 2022, the top bracket was taxed at just 37 percent.

How do taxes affect economies and societies?

Governments typically use tax revenue to fund public services that accelerate economic and social development, such as schools and health-care systems. With less taxation—whether due to lower rates or greater difficulty collecting taxes—governments have fewer resources to dedicate toward public services.

To understand the development-related effects of tax policy, let’s compare two countries: Paraguay and Uruguay. Between 2005 and 2010, the two South American nations had relatively similarly sized economies—or gross domestic products (GDPs). However, over that same period, Uruguay collected more than twice as much tax revenue as a percentage of GDP than Paraguay. In addition, Uruguay spent twice as much on health care, social security, and other welfare programs. In 2010, Uruguay covered 97 percent of its population with health insurance, compared to just 23 percent in Paraguay.

Decisions about how a government should tax and spend are known as fiscal policy. Fiscal policy is fiercely debated in many countries and a common source of sharp partisan rifts, with policymakers often arguing over tax rates and the allocation of tax revenue.

What challenges do governments face collecting taxes?

Every country collects taxes differently. Some countries have steep income-tax rates—like Finland, which collects nearly 60 percent from its highest earners. Others choose not to impose income taxes at all—like Qatar, which collects most of its government revenue from the country’s highly lucrative oil and gas industry.

However, not every country that wishes to collect taxes is necessarily capable of doing so. Let’s explore a few roadblocks to tax collection.

Informal economies: Billions of people worldwide work in roles that governments neither monitor nor regulate. Informal sector jobs often include small-plot farming, temporary construction work, craft making, and housekeeping. In Africa, roughly 86 percent of all paid laborers work in this informal economy. Without sufficient record keeping, governments struggle to provide services for or collect taxes from this workforce.

Conflict: In many countries experiencing civil unrest, governments struggle to collect taxes from their citizens. Often, they cannot reach those citizens because opposition forces control portions of the country. In Somalia, for example, the militant group al-Shabab collects nearly as much in taxes as the central government in Mogadishu.

Corruption: Corrupt government officials—particularly in resource-rich countries—sometimes use tax revenues for personal enrichment rather than public services. In 2019, the International Monetary Fund found that curbing corruption could generate an additional $1 trillion in worldwide tax revenue.

Tax avoidance: Individuals and corporations can exploit loopholes in tax laws or use other means to lower their tax burden. Moving money to low-tax countries—or tax havens—is one form of tax avoidance that has become increasingly common. In fact, extremely high-net-worth individuals held about 10 percent of the world’s GDP ($8.7 trillion) in tax havens in 2017. Although many governments discourage tax avoidance, the practice is often legal.

Tax evasion: Individuals and corporations can underpay or altogether fail to pay their tax obligations. Unlike tax avoidance, this practice is illegal. In 2021, the Internal Revenue Service—the federal body responsible for collecting taxes in the United States—estimated that the country loses $1 trillion in taxes every year, largely due to tax evasion by wealthy individuals and corporations.

Is there a global tax policy?

When taxes are progressive and broadly paid, they can redistribute wealth between income groups and reduce economic inequality. But in recent years, taxes have become less progressive, with average top personal-income taxes declining by more than 15 percent across advanced economies since 1981.

Experts maintain that top tax rates have fallen to appease individuals and corporations seeking low-tax zones. In France, for instance, an estimated forty-two thousand millionaires rescinded their citizenship between 2000 and 2012 to avoid paying a wealth tax.

Today, however, many governments are pushing for more equitable tax structures worldwide. In particular, policymakers seek to prevent corporations from moving their profits to low-tax shelters overseas to avoid paying higher taxes at home. To this end, 136 countries agreed in 2021 to a global minimum corporate-tax rate. Once implemented in 2024, this policy would ensure that the wealthiest corporations pay a minimum of 15 percent in taxes regardless of their location. An overwhelming majority of countries—accounting for 90 percent of the global economy—have already agreed to the policy.

Should this policy go into effect, it would only further vindicate Benjamin Franklin’s claim about the inevitability of paying taxes.