Two Koreas, Two Development Policies

How did North Korea and South Korea turn out so differently? Learn about the history of Korea after World War II and how economic policies shaped the region.

South Korea is one of the world’s most successful economies. It’s home to billion-dollar corporations like Samsung and produces some of the best high-tech electronics. But just across the border, North Korea is one of the most impoverished countries in the world. How can two countries with the same language, culture, and history—that were, not long ago, one united country—turn out so differently?

North and South Korea had been one nation for over a thousand years. Theoretically, they could have developed similarly after splitting in 1945, at the end of World War II. In fact, North Korea possessed the resources to outpace the south in development. But the political and economic decisions their leaders made destined the countries for completely different futures.

The Division of the Koreas

From 1910 until 1945, Japan ruled Korea in a brutal occupation. The colonial rule ended when Japan surrendered to the Allied forces at the end of World War II and was forced to give up its colonies. In turn, the Soviet Union and the United States—victors over Japan—moved in, jointly occupying the Korean Peninsula under two spheres of influence. The Soviets occupied the north, the Americans oversaw the south, and the line known as the thirty-eighth parallel divided the peninsula.

The division was supposed to be temporary, but two countries with authoritarian governments began to form: a communist country under Kim Il-sung in the north and a capitalist one under Syngman Rhee in the south. Both sides claimed to be the legitimate government of all Korea.

Tensions peaked in 1950 when North Korea, with Soviet and Chinese backing, invaded South Korea, starting the Korean War. The United States came to the defense of South Korea, fearing that North Korea’s attempt to take over the entire peninsula could turn more countries communist. In 1953, the two sides reached a stalemate. Hundreds of thousands had died on both sides in the war, and the peninsula remained divided along the thirty-eighth parallel.

After the Korean War: 1953–60

North Korea

Kim Il-sung, a World War II Korean general trained by the Soviets, quickly consolidated power in North Korea. He proclaimed himself its supreme leader and arrested his political opponents almost immediately after the Korean War. To create a cult of personality, he ordered the construction of hundreds of statues of himself around the country and had North Korean textbooks claim that he single-handedly defeated the Japanese in World War II. Kim Il-sung believed that cultivating this almost mythical status would allow him to rule North Korea without question or opposition.

Central to this strongman political rule, Kim established a command economy (also known as a planned economy) in North Korea, where the government alone controlled the entire country’s resources. Kim stated the guiding principle of the economy would be juche, or self-reliance. Juche refers to the idea that North Korea should be able to rely on itself for all purposes—technology, defense, and consumer goods. The North Korean economy initially showed promise. North Korea controlled 80 percent of the peninsula’s coal and minerals as well as the vast majority of heavy machinery from Japanese colonial rule; this advantage allowed the country to rapidly industrialize in the first decade after the Korean War. With total power in its hands, the government ensured that all citizens attained primary and secondary education, and it leveraged its large supply of machinery and electrical power to produce goods and grain for its people.

South Korea

Unlike the north, South Korea had few natural resources, and most of its population worked in small-scale agriculture. The fear of recreating colonial dependence on Japan meant that South Korea shied away from trading with Japan, whose economy was booming throughout the 1950s. In doing so, South Korea missed out on a clear opportunity for economic growth. To make things worse, the country was in political turmoil after a rigged election and unpopular constitutional amendments, and its unstable economy did not appeal to foreign investors. Instead, South Korea relied on large amounts of U.S. aid to keep the economy afloat. One decade after the Korean War, South Korea had few prospects for growth.

Juche and the Rise of Park Chung-hee: 1961–90

North Korea

Kim set ambitious economic goals for the 1960s based on the progress of the previous decade. But the country faced new challenges. Relations between North Korea’s two allies, the Soviet Union and China, were deteriorating. In response, Kim increasingly focused on juche rather than side with one of the communist heavyweights and risk antagonizing the other. In 1962, the Kim regime announced its “juche for self-defense” policy, which prioritized the military sector, devoting three quarters of all government investment to heavy industry and weapons production.

This focus on military strength came at a cost. The government paid less attention to running factories for grain and commercial products and failed to set up mechanisms to accurately collect production statistics. North Korea’s economy relied on the government to set prices, production, and income, but doing so was fairly difficult without precise statistics in hand. Ineffective government oversight led to inefficiency, poor management, and corrupt administration. Effectively, North Korea had a planned economy with no plan. The government poured money into the military, but overall production lagged.

By the mid-1970s, it was clear that juche was failing. As economic growth plateaued, North Korea’s self-imposed isolation made it difficult for the country to benefit from advanced foreign technology such as computers and electronics. And the government’s neutral stance between China and the Soviet Union resulted in aid cuts from both countries. North Korea was focused on little other than military strength, and military officials wielded immense influence, creating a “military first” politics known as songun. By the 1980s, North Korea built up its army to one million men—one-tenth of the male population—as a way for the regime to display power and control to its citizens and the outside world. Kim Il-sung kept the army well fed, but ordinary people, who relied on their government for income and food, suffered.

South Korea

Meanwhile, economic development was picking up in the other half of the Korean Peninsula. In 1961, General Park Chung-hee seized power through a coup and instituted a new vision for the country’s economy, albeit alongside political repression.

Park, unlike previous South Korean leaders, admired Japan and its export-oriented economic system. He pushed for a Japanese-inspired economy, which mostly had characteristics of a market economy, as opposed to North Korea’s insular, planned economy.

Under this model, the South Korean government imported raw materials, maintained cheap labor that assembled final products, and exported those final products. South Korea’s petroleum industry is a perfect example: The country lacks natural oil reserves, but it built its first oil refinery in 1964, purchased crude oil from Middle Eastern countries at a low cost, refined the crude, and sold petroleum products internationally. South Korea benefited from a rewarding relationship with the United States, which became the biggest market for South Korean goods by 1970.

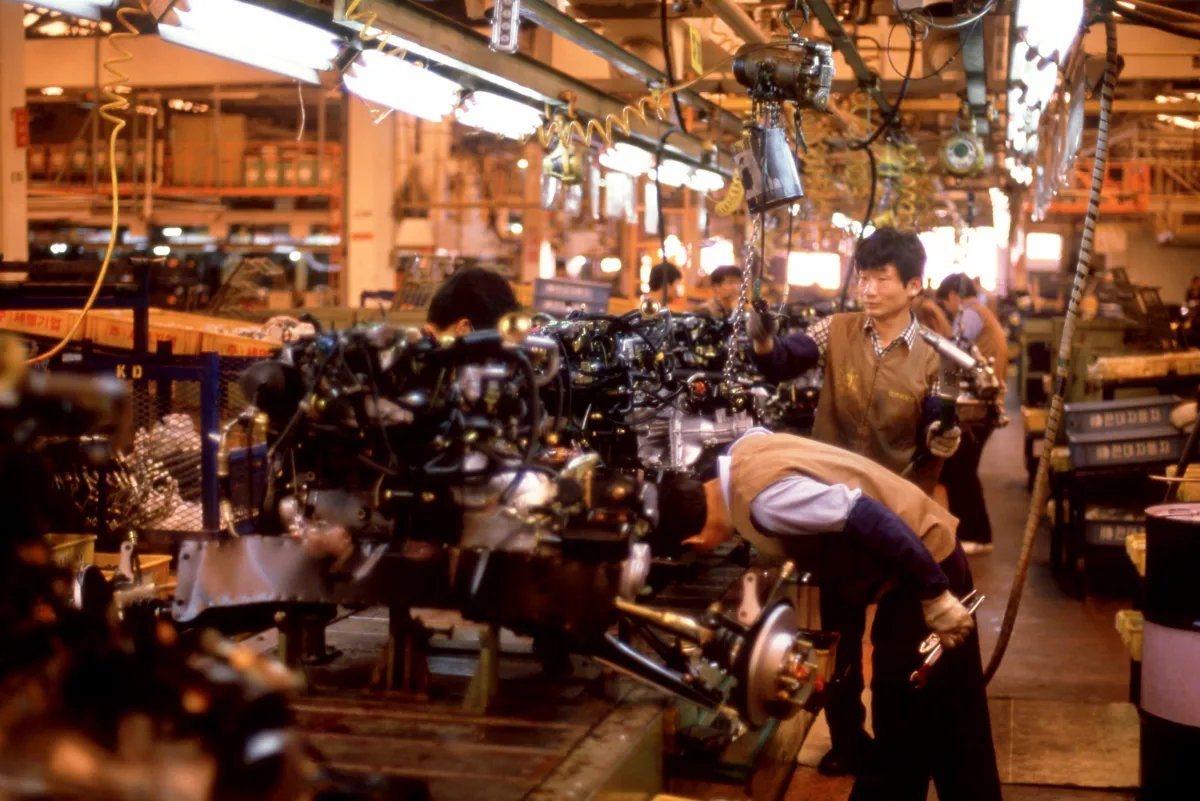

South Korea’s export-oriented system achieved dramatic results: Growth rates soared over 10 percent throughout the 1970s, far exceeding the global 4 percent average at the time. During the 1980s, South Korea established itself as a major producer of automobiles, ships, TV sets, and computer chips. A handful of giant single-family conglomerates—groups that run multiple companies across different industries—drove much of this growth. These conglomerates, known as chaebol, were private businesses, but they built close relationships with the government. The government incentivized chaebol to increase their production by providing them with low-interest loans based on their performance, measured meticulously with clear benchmarks. The strategy worked, and chaebol cooperated with the government to produce and export goods at increasingly efficient rates. They grew so quickly that they eventually encompassed industries as varied as food and amusement parks and automobiles. Perhaps the most famous chaebol, Samsung, started out as a dried-fish and noodles business and diversified into insurance, retail, and electronics. Where the North Korean government poorly managed its factories and refused to open up to trade, the South Korean government leveraged its private sector and free markets to achieve success.

Unlike the insular North Korea, South Korea benefited from U.S. humanitarian aid and the presence of sixty thousand U.S. troops stationed near the border with North Korea to maintain stability throughout the 1960s (this number leveled off around forty thousand in the following decades). Some South Koreans worried that too much dependence on the United States—both as a military protector and also as a market for exports—was risky. But the freedom to invest money outside the military and into businesses undeniably spurred South Korean growth.

After the Fall of the Soviet Union: 1991–Present

North Korea

The North Korean economy stagnated throughout the 1970s and 1980s, and the country defaulted on its international loans in 1975. But the economy stayed afloat thanks to one major exception to its self-reliance policy: the Soviet Union provided heavily subsidized energy imports and cheap machinery that, together, were worth over 60 percent of North Korea’s gross domestic product (GDP). However, that benefit ended when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, bringing North Korea’s economy down with it. North Korea’s agricultural production crashed after the country was cut off from the fuel it needed to operate farm machinery and harvest grain. In 1994, Kim Il-sung—who had ruled North Korea since its creation for over forty years—died. His son, Kim Jong-il became the country’s new leader, but he lacked economic experience. Even at this crossroads, Kim Jong-il clung to the same juche model rather than look outward for new food and energy sources.

To this day, North Korea suffers from extreme poverty and a heavy reliance on energy imports and economic aid, mostly from its now-closest ally, China. It continues to disproportionately invest in its military just as it has for the last sixty years, particularly by pursuing nuclear weapons and ballistic missile programs. North Korea remains a largely isolated country with only limited market reforms. Its newest leader, Kim Jong-un—Kim Jong-il’s son who took over in 2011—has relaxed juche by courting stronger economic relations with India, European countries, and others. But the United States has imposed heavy sanctions on North Korea due to its nuclear weapons program and blocked any foreign business or individual who does business with North Korea from doing business in the United States. This pressure has led to many foreign businesses giving up on investing in or trading with North Korea, weakening the prospects for economic growth.

South Korea

South Korea’s export-oriented policies have transformed it from one of the poorest countries in the world to a developed, high-tech country in just fifty years. It continues to incentivize chaebol to maximize production and profits off exports. The country no longer receives humanitarian aid and successfully transitioned from authoritarianism to a modern democracy in 1987.

That’s not to say that the country is problem-free. The 1997 Asian financial crisis badly hurt the South Korean economy, which needed a bailout from the International Monetary Fund. A bribery scandal in 2016 exposed alarming corruption in the country’s business and political community, and led to the impeachment of the South Korean president. But the economy has withstood these shocks. South Korea has relatively low levels of inequality, free and high-quality health care, and a high standard of living.

In North Korea, the Kim regime and the country’s elite enjoy luxurious lifestyles while much of the population is malnourished. The regime’s failure to improve economic conditions has had devastating effects on the overall health of North Koreans, who, on average, live eleven years fewer than their South Korean counterparts.

The thirty-eighth parallel today not only signifies a separation line of the two Koreas but also serves as a reminder that developmental strategies can either create conditions for economic success or consign an economy to failure.