Resource Conflicts, Explained

How do water, oil, and gold cause wars? Learn how competition over natural resources fuels and finances fighting and how climate change intensifies those conflicts.

Throughout history, people have waged countless wars for countless reasons, fighting over issues such as territory, religion, and political differences.

Competition over natural resources is yet another major driver of conflict. In many cases, control over vital or valuable resources like diamonds, oil, and water has directly caused or compounded violence. In other instances, selling lucrative resources has financed or prolonged conflicts rooted in entirely separate issues.

Moving forward, experts anticipate climate change will intensify resource-driven conflicts. Already, twelve of the twenty most climate-vulnerable countries [PDF] have endured conflict in recent years amid heightened resource scarcity.

Read on to learn more about eight natural resources driving and financing fighting around the world.

Coca

What is it? Coca is a plant whose leaves can produce cocaine. Coca grows primarily in South American countries such as Bolivia, Colombia, and Peru.

How does it drive conflict? Cocaine production is highly lucrative. For decades, global demand—particularly from Europe and North America—has fueled a multibillion-dollar market. Several militant groups have used coca cultivation and cocaine trafficking to finance conflicts.

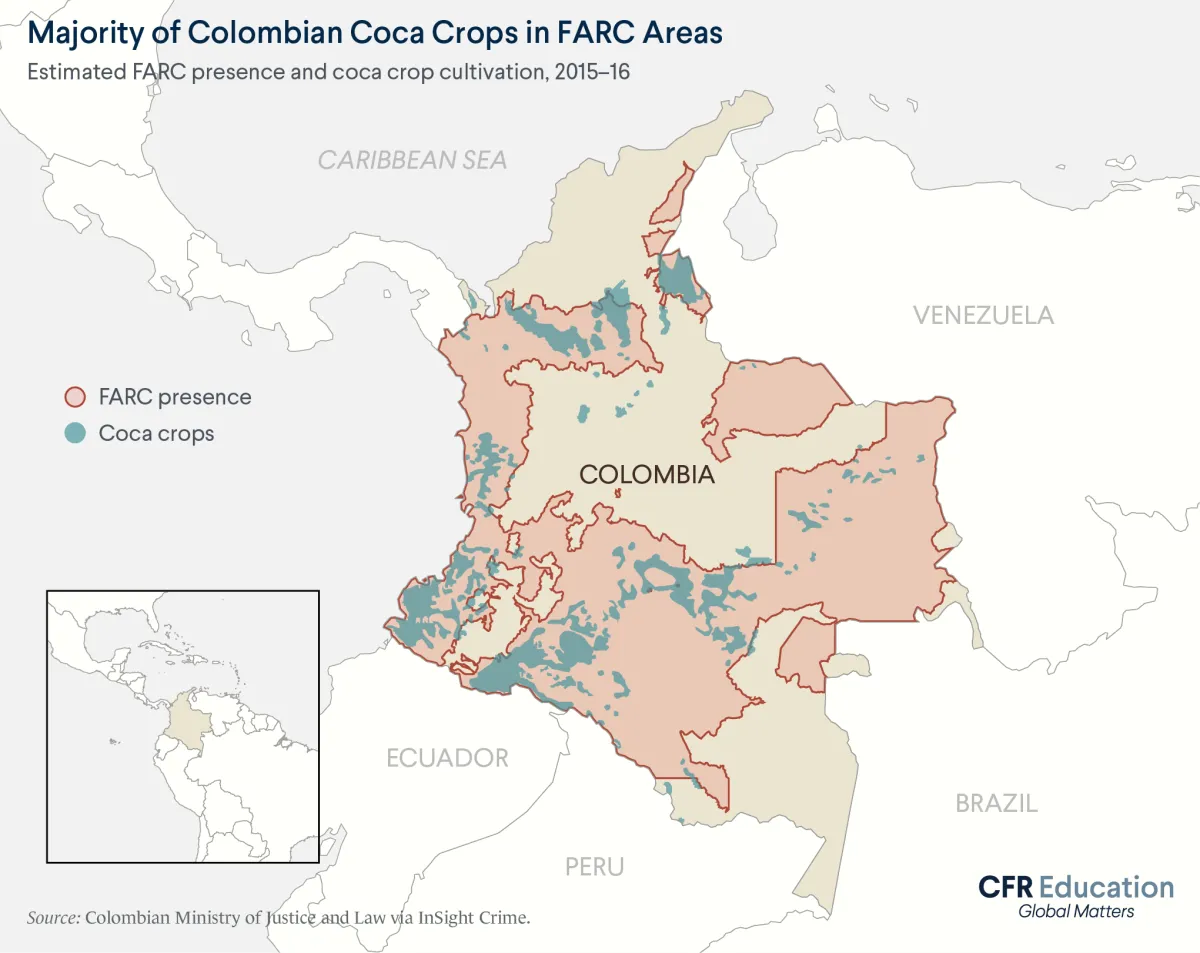

Example of conflict: From 1964 to 2016, Colombia endured a deadly conflict between the government and a left-wing militant group called the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

In the 1970s, the FARC began cultivating coca and trafficking cocaine to finance its guerrilla campaign. The FARC would come to control up to 70 percent of Colombia’s coca-growing regions. By the early 2000s, Colombia was supplying up to 90 percent of the world’s cocaine. FARC controlled an estimated 60 percent of Colombia’s cocaine exports to the United States.

The operations were extremely profitable. Former Colombian Defense Minister Juan Carlos Pinzón estimated that coca and cocaine generated up to $3.5 billion annually for the FARC.

Diamonds

What are they? Diamonds are rare carbon-based minerals. They have been discovered in dozens of countries. In particular, Southern Africa is a top mining region in the world.

How do they drive conflict? The rarity and brilliance of diamonds make them highly valuable gemstones. Global rough-diamond production generated nearly $14 billion in 2019. Several militant groups, particularly in Africa, mine and traffic diamonds to finance conflicts.

Example of conflict: In 1991, war broke out between the government of Sierra Leone and a rebel group called the Revolutionary United Front (RUF). To support its campaign, the RUF conducted illicit diamond mining and smuggling. RUF used their diamond operations to garner up to $125 million annually.

In 2000, Sierra Leone’s UN ambassador, Ibrahim Kamara, stressed the significance of the gemstones, stating that “the root of the conflict is and remains diamonds, diamonds, and diamonds.”

Sierra Leone’s eleven-year civil war, which killed at least 70,000 people and displaced 2.6 million, shed light on the sinister role diamonds play in driving conflict. In the early 2000s, governments worldwide established the Kimberley Process. This international regime monitors the diamond trade and ensures diamonds do not finance rebel groups.

Gold

What is it? Gold is a natural element that serves many purposes, including coinage, jewelry, and electrical wiring. For over a century, South Africa produced most of the world’s gold. However, in the early 2000s, China, Russia, and Australia became top exporters.

How does it drive conflict? Gold’s varied uses make it a valuable resource. The global gold-mining market is expected to grow from $214 billion in 2021 to nearly $250 billion by 2026. Its lucrativeness allows governments and insurgent groups to use gold sales to finance conflict.

Example of conflict: For decades, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has experienced civil war. Political violence between a weak central government and numerous militant groups has created a power vacuum. The result is a severe humanitarian crisis.

Conflict minerals have long financed fighting in the DRC. In recent years, gold smuggling has provided particularly significant revenue—roughly $400 million annually—for armed groups in the eastern DRC.

Armed groups have used gold revenue to buy weapons and influence corrupt officials. Moreover, the illegal gold trade starves the government of resources; upward of 90 percent of the DRC’s gold is trafficked out of the country.

Lithium

What is it? Lithium is a chemical element and the lightest metal on earth. Used primarily in electric batteries, it powers everything from cell phones to electric vehicles. Numerous countries mine lithium, including the United States, Argentina, Australia, Bolivia, and Chile.

How does it drive conflict? As demand for smartphones and electric vehicles has soared in recent decades, so too has demand for lithium. The resulting boom, however, has fueled conflict between Indigenous communities, governments, and extraction companies in lithium mining areas.

Example of conflict: The border region between Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile is rich in lithium. The area, known as the lithium triangle, has become popular with mining companies seeking to extract this natural resource. However, the rush for lithium has caused numerous issues.

Across the region, Indigenous communities have mobilized to prevent mining on their land. Aside from territorial claims, local groups have raised environmental concerns. Lithium extraction requires considerable water use—a major issue in the arid region. Over the years, the area’s Indigenous groups have protested the proliferation of lithium mines, shutting them down at times with roadblocks.

Oil

What is it? Crude oil, also known as petroleum, is a hydrocarbon mixture that serves as a major source of fuel, powering everything from lawn mowers to cars. Oil extraction occurs throughout the world, with the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Russia leading production.

How does it drive conflict? Oil has powered the world for more than a century. Global demand has given oil-producing countries enormous wealth and geopolitical influence. The natural resource has also contributed to competition and conflict.

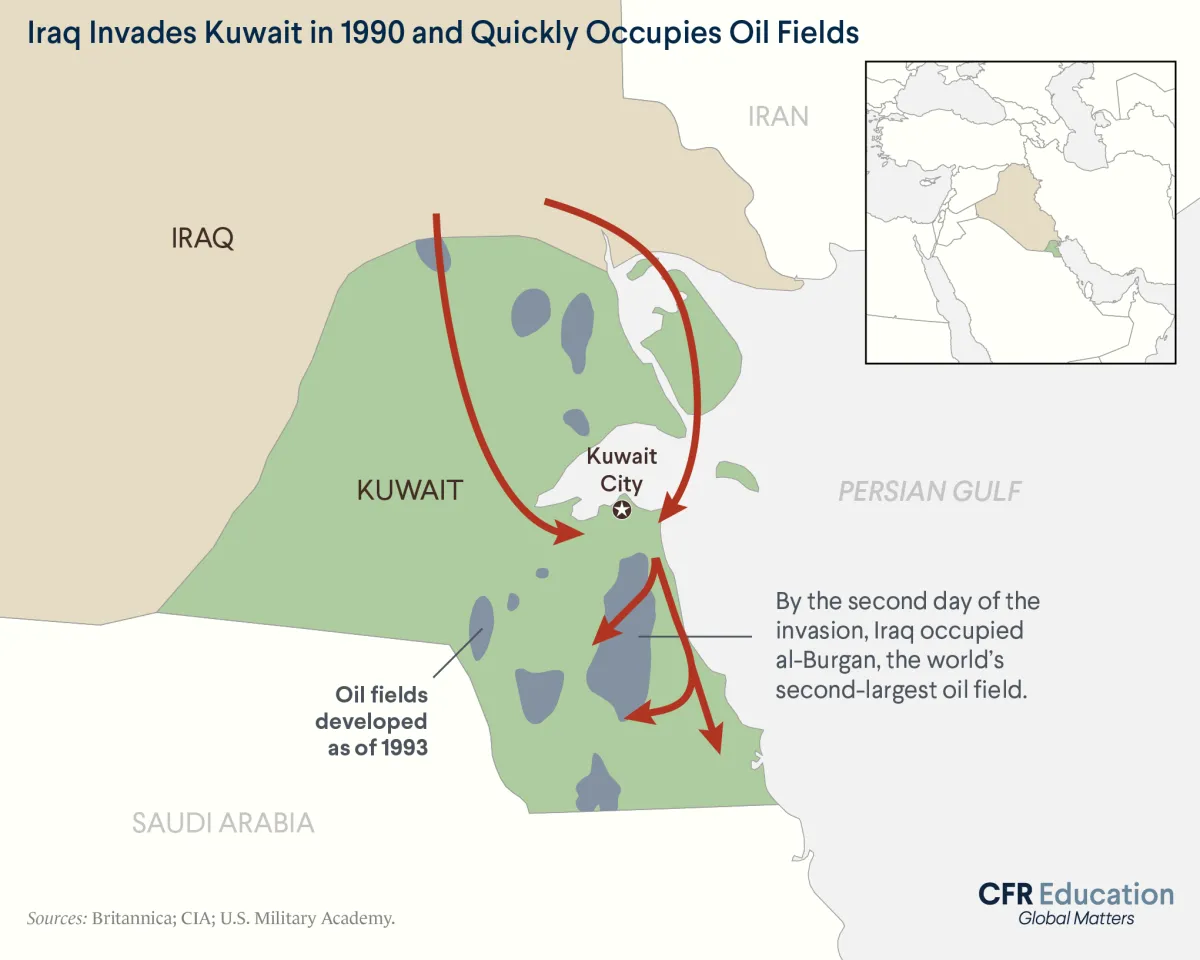

Example of conflict: The Middle East is home to over 50 percent of the world’s proven oil reserves and has long experienced conflict over the resource. Take Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990.

In the months prior, Iraq accused Kuwait of overproducing oil to lower prices and deprive Baghdad of oil revenue. Then, in August 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait, hoping to take control of its substantial oil reserves.

The United States and other countries condemned the invasion. Washington objected to the violation of Kuwait’s sovereignty and the resulting disruption to the global oil supply. Within months, a U.S.-led coalition liberated Kuwait.

Poppy

What is it? Poppy is a plant whose seeds can produce drugs such as opium and heroin. Illicit poppy cultivation occurs in just a handful of countries, with Afghanistan producing as much as 90 percent of the world’s supply in recent years.

How does it drive conflict? Poppy cultivation and opium production is lucrative. Afghan opium supplies Asia, Europe, and, to a lesser extent, North America, creating a multibillion-dollar industry. Militant groups have used opium revenue to fund their operations.

Example of conflict: In 2001, following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the United States toppled the Taliban in Afghanistan, installing a new government in Kabul. The invasion kicked off a deadly and ultimately successful twenty-year Taliban insurgency against the occupation and the U.S.-backed Afghan government.

Poppy cultivation and opium production heavily supported the Taliban, generating hundreds of millions of dollars annually from taxation and trafficking.

Timber

What is it? Timber is the wood from trees that can be processed into beams and planks for construction. Top-producing countries include the United States, China, and Russia.

How does it drive conflict? Global demand has created a lucrative illegal timber industry. Criminal and insurgent groups have used the illicit timber trade—which generates up to $152 billion annually—to finance their operations.

Example of conflict: In the late 1970s, the Khmer Rouge brutally ruled Cambodia, killing and displacing millions. The regime fell in 1979 after Vietnam invaded Cambodia. However, the country continued to endure deadly political violence.

For decades, the government and the Khmer Rouge fought a civil war that both sides partly financed through timber sales. Timber revenue was especially critical for the Khmer Rouge, leading the UN Security Council to call for a ban on all Cambodian timber exports in 1992.

Nonetheless, the Khmer Rouge continued to earn an estimated $10 million to $20 million per month from illegal timber in the mid-1990s. The organization eventually collapsed in the late 1990s after its leader, Pol Pot, died.

Water

What is it? Water is, well, water—the most vital resource needed to sustain life. Only 3 percent of the world’s water is freshwater, and only about one-third of that freshwater is readily accessible.

How does it drive conflict? Almost three billion people worldwide lack regular access to water for at least one month of the year. That figure will increase as climate change further exacerbates water scarcity. As access to water lessens, water-related conflict has escalated both between and within countries.

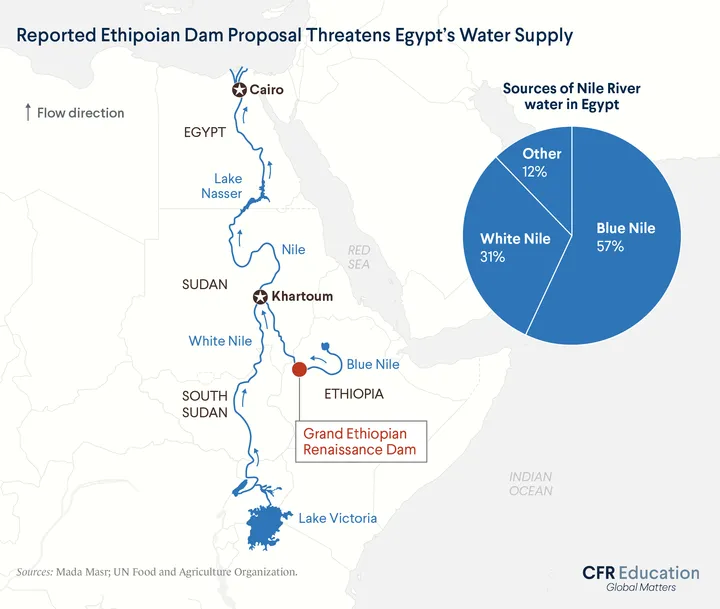

Example of conflict: In 1988, Egyptian diplomat and future UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali warned that “the next war in our region will be over the waters of the Nile, not politics.” Indeed, the Nile River has long been a flashpoint between Egypt and its neighbors, particularly Ethiopia.

For decades, Egypt controlled the Nile. In recent years, however, Ethiopia has partially dammed the Nile to generate hydroelectric energy. Ethiopia claims the dam will not affect the Nile’s downstream flow.

Egypt, meanwhile, has called the dam an existential threat. Officials fear that filling the dam could limit Egypt’s already strained water resources, harming the 95 percent of Egyptians who live along the Nile. In response, Egypt has taken actions ranging from hacking Ethiopian government websites to suggesting military action.

Nonetheless, in early 2022, Ethiopia began producing electricity in the dam—a move that drew swift condemnation from Egypt.