People and Society: Sub-Saharan Africa

With over one billion people living in forty-nine countries, sub-Saharan Africa is one of the world’s most diverse regions.

With over one billion people living in forty-nine countries, sub-Saharan Africa is one of the world’s most diverse regions. In Cameroon alone, a mix of Muslims, Christians, and adherents of local religions speak over two hundred languages and belong to roughly two hundred and fifty ethnic groups. Sub-Saharan Africa is also home to the world’s youngest and fastest-growing population; these statistics point to great economic potential but also to great challenges, as governments and growing cities struggle to keep pace with growth. Migration forced by conflict and environmental changes also contributes to sub-Saharan Africa’s rapidly changing demographics. Health and education, especially for women and girls, continue to improve dramatically but still lag significantly behind other regions.

Region’s Population Is Young, Growing

Sub-Saharan Africa is already one of the world’s most populous places. But what really sets the region apart is how fast its population is growing and how young it is: between 1950 and 2010, the region’s population grew from 186 million to 856 million, 43 percent of whom are people under the age of fourteen. At this rate, one of four people in the world will be African in just a few decades. These massive demographic shifts will pose challenges for the region but also provide opportunities. By 2035, sub-Saharan African will be home to more working-age people (aged 15–64) than all other regions combined.

A Region on the Move

Between 2010 and 2017, people from sub-Saharan African countries made up nine of the ten fastest growing groups emigrating, or leaving their countries to live in another. But most of these migrants will not leave the region. Instead, the majority will settle in neighboring countries. This mass migration has a variety of root causes. A large number of people have been displaced by violent conflict, such as the ongoing civil war in South Sudan. Many are economic migrants looking for better opportunities and who often head from landlocked countries to more prosperous coastal countries.

Neighboring Countries Shoulder Refugee Burden

Sub-Saharan Africa bears the brunt of the world’s refugee crisis. As of 2017, seven of the top ten countries producing refugees were in sub-Saharan Africa. And most refugees remain in the region, often fleeing to neighboring countries. For example, roughly 90 percent of South Sudan’s refugees, who numbered 2.5 million as of May 2018, fled to three African countries: Uganda, Sudan, and Ethiopia. Often, neighboring countries absorbing refugee populations lack the resources to provide for their own people. As a result, tens of millions of refugees and internally displaced persons (displaced people who have stayed within their country’s borders) face hunger, disease, sexual assault, and other dangers. In almost every case, women and children are disproportionately affected.

Climate Refugees Represent Growing Crisis

In recent years, the number of climate refugees, or people forced to move from their homes due to natural disasters, droughts, and other calamities caused by the warming planet, has grown rapidly. Though the numbers can be difficult to calculate because this migration category is still being defined by governments and international law, the World Bank estimates that climate refugees in sub-Saharan Africa could number over 85 million by 2050. In one example, Lake Chad, which supports nearly 25 million people in 4 different countries has shrunk by 90% in the past 60 years increasingly displacing many of the people who depend on its water. Like those displaced by conflict, climate migration also disproportionately affects the already vulnerable, like poorer populations.

Opportunities Draw Millions to Cities

The region is home to two of the largest cities in the world by population: Lagos in Nigeria and Kinshasa in Democratic Republic of Congo. Rural-to-urban migration has brought some economic prosperity to many in the region, as they leave farming for more stable, higher-wage jobs in cities. But not everyone seeking those jobs has found them, and many African cities have become crowded and expensive. Still, the percentage of sub-Saharan Africans living in cities is expected to continue increasing further, reaching 50 percent by 2030.

Countries Cope with Many Languages

There are seven thousand languages spoken across the world. And about two thousand of them can be found in sub-Saharan Africa alone. South Africa has eleven official languages and in Nigeria, conversations take place in more than 520 languages, many spoken by tens of millions of people. Such a high degree of linguistic diversity can have political, societal, and economic implications, especially if many people in the same country cannot understand each other. To account for this, many countries have one or multiple official languages to conduct government business.

In Some Cases, Ethnic Diversity Poses Challenges

Sub-Saharan Africa’s diversity is also reflected in its hundreds of ethnic groups. For example, Chad’s fifteen million people belong to roughly one hundred different ethnic groups. Occasionally, the region’s ethnic diversity can lead to divisions or violent conflict but most sub-Saharan Africans co-exist peacefully. And when ethnic diversity is identified as a root cause for conflict, it’s often accompanied by other factors. For example, in the north near the Sahara Desert, climate change continues to displace Muslim herders, who are then forced to seek grazing land in areas populated by Christian farmers who come from multiple, smaller ethnic groups, a combination of ethnic, religious, environmental, economic factors that can lead to violent clashes.

Islam and Christianity Sweep the Region

Religion plays a central role in sub-Saharan African life and some religious leaders wield enormous influence, both at the local and national level. Many people in the region continue to practice traditional African religions while remaining committed to Christianity or Islam. Christians in sub-Saharan Africa now make up over a quarter of the religion’s global population. Given the monumental demographic shifts occurring in the region, these numbers are set to grow dramatically. In 2015, roughly 27 percent of the world’s Christian population and 15 percent of its Muslim population called the region home. By 2060, 40 percent of the world’s Christians will live in sub-Saharan Africa along with 27 percent of the global Muslim population.

One Step Forward, Two Steps Back for Gender Equality

Gender equality is progressing at different rates across the region. In some countries, harmful practices such as early marriage and female genital mutilation (FGM) significantly restrict girls’ health and well-being. Meanwhile, in other countries, women hold significant leadership roles. In Rwanda, female representatives make up 61 percent of the legislature. (In the U.S. Congress, it’s 20 percent.) Originally one result of a genocide that killed mostly men, the transition of Rwandan women into politics and the workforce has made the country sixth in the world in terms of equality between men and women, according to the World Economic Forum.

Lagging Behind in Education and Literacy

Sub-Saharan Africa has some of the lowest literacy rates in the world: in twelve countries, less than 50 percent of children and adults are literate, and less than half of the population enrolls in high school. Yet over the past decade, the number of children enrolling in primary school has increased rapidly and now averages over 90 percent. However, these gains are not equally spread out: girls’ secondary school enrollment hovers around just 8 percent. Where girls have been educated, however, a domino effect has occurred: girls who receive an education are more likely to marry later in life, have fewer children, and have a higher quality of life overall.

Advancements Lead to Better Health, Longer Lives

Over the past few decades, people have been living longer, healthier lives across sub-Saharan Africa. In Malawi, life expectancy rose from forty-four years in 2000 to nearly sixty-three in 2014. Other important strides have been made: polio has virtually been eradicated, more children are receiving vaccinations for infectious diseases like measles every year and deaths from AIDS declined from almost two million in 2005 to less than a million in 2017. The HIV/AIDS epidemic is still a serious problem in the region but over half the people living with HIV now have access to treatment in the form of antiretrovirals, also known as ARVs.

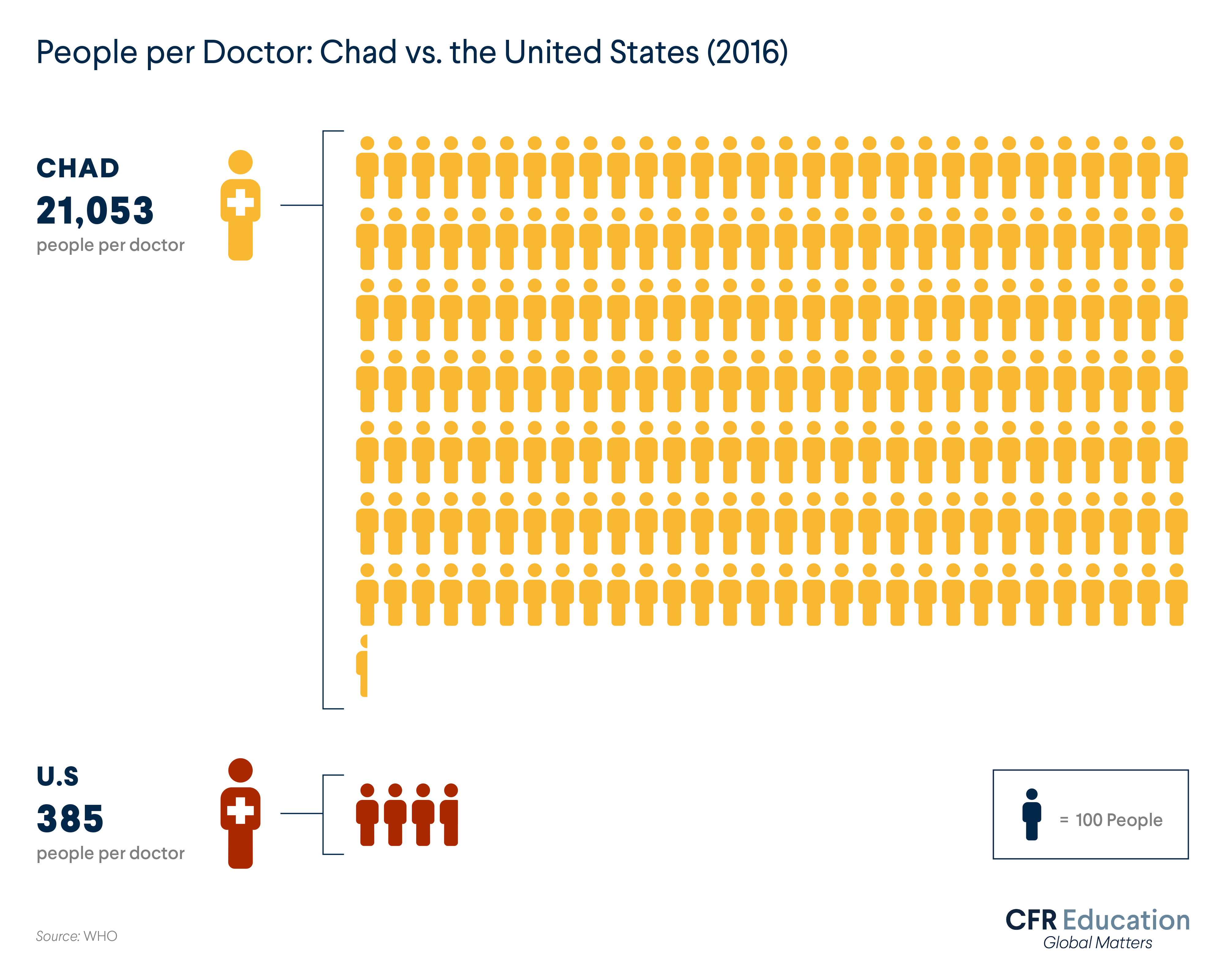

Access to Healthcare Remains a Challenge

Rising life expectancies across the region have coincided with rising levels of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) such as cancer and diabetes. NCDs often require long-term treatment, a challenge in a region where access to health care is limited. Basic sanitation often remains out of reach, leading to high rates of waterborne illnesses such as cholera. And maternal and child mortality rates remain among the highest in the world. These problems are often amplified because the region lacks healthcare professionals. According to the World Health Organization, sub-Saharan Africa shoulders 25 percent of the world’s disease burdens (a way to measure the impact of a specific health problem), but only has 3 percent of the world’s doctors.

Cell Phone Boom Connects the Region

In a region where gaining access to basic necessities can be a challenge, one staple of modern life has proliferated. Three out of every four sub-Saharan Africans now have an active cell subscription in the form of a SIM card, and roughly half of the population has a physical cell phone. Some estimate that more sub-Saharan Africans have access to cell phones than electricity. And the explosive growth of the mobile phone industry has affected almost every part of life in the region. Telemedicine is helping make up for a lack of trained healthcare professionals in rural areas. Business owners and farmers use their phones to buy solar energy and trade crops. And mobile money transfers have given people across the region access to capital for the first time.

Ebola Informs Coronavirus Response, But Health-Care Challenges Persist

The deadly disease Ebola ravaged parts of West Africa between 2014 and 2016. More than eleven thousand people died as poor health infrastructure, weak monitoring systems, and mistrust of health officials complicated the response. When COVID-19 first struck the continent in early 2020, many countries drew on the lessons learned fighting Ebola to meet this new challenge. Kenya and Nigeria quickly closed schools, while Uganda banned large gatherings before confirming even a single case. Senegal began developing a $1 COVID-19 testing kit and mobilized health-care workers trained during the Ebola crisis to monitor for symptoms of the novel coronavirus. Liberia meanwhile managed public distrust by hiring health-care workers directly from local communities. Still, challenges persist. Unlike countries such as Germany or South Korea, which have vast, well-financed health-care systems, many sub-Saharan African countries lack access to vital lifesaving equipment. As of May 2020, ten countries in the region lack a single ventilator, while the Democratic Republic of Congo has just one for every twenty million citizens.

Pandemic Threatens Unprecedented Food Insecurity

COVID-19 threatens to double the world’s severely hungry population to 270 million by the end of 2020. This crisis is particularly acute in sub-Saharan Africa, where one in five people is already undernourished. There, public health measures intended to slow the spread of the deadly virus—such as lockdowns, travel restrictions, and border closures—have also made the transportation of food from farms to markets far more difficult. A severe locust plague in East Africa has further compounded this challenge. As a result, the region’s agricultural output is projected to decrease by as much as 7 percent in 2020. In addition, sub-Saharan Africa imports approximately $35 billion of food annually. But with COVID-19 jeopardizing food supplies worldwide, many countries that traditionally sell food to the region—including Cambodia, India, and Vietnam—have reduced or banned exports in order to provide for their own citizens. The UN World Food Program warns of impending famines of “biblical proportions” due to these disruptions to food supply chains.

Gender-Based Violence Surges Amid COVID-19 Lockdowns

COVID-19 is driving an increase in gender-based violence, as monthslong lockdowns force survivors to live in close and constant confinement with their abusers and distance survivors from critical support networks. In Kenya, domestic violence calls surged 34 percent in the first three weeks of COVID-19 lockdowns, and in South Africa eighty-seven thousand such calls were made in just the first eight days. Now, months into the pandemic, many of the social and economic drivers of this violence persist, including school closures and unprecedented financial strain. Around the world, women have taken to the streets, calling on their governments to improve services such as hotlines and shelters for survivors of gender-based violence, and the UN secretary-general has called for a “cease-fire” on domestic violence.