National Politics: Middle East and North Africa

From press freedom to reform, learn about the issues shaping ten countries today.

In 2011, millions of protesters in places like Egypt, Syria, and Tunisia rose up to demand political, economic, and social reforms. Their governments were highly repressive in response; for decades, these regimes had ruled with unchecked power. The protests quickly spread to other countries, marking a period of region-wide revolution known as the Arab uprisings (sometimes referred to as the Arab Spring). It was a time of promise—a once-in-a-generation opportunity for deep, structural reform.

But, nearly a decade later, much of that promise has faded. Despite important progress, democracy in the Middle East remains challenged. As a result, the fight for democratic rule remains a continued lynchpin in the political stories of many countries in the region. Despite region-wide calls for social and political reform, many countries of the region are ruled by strongmen, and lack liberal, democratic institutions—such as free speech and freedom of the press.

There is some democratic promise in the region: Israel, for example, is a democracy and Tunisia has made great progress. Still, half of all countries in the region have an unelected head of state. Several authoritarian countries, such as Egypt, Iran, and Syria, offer the veneer of democracy while in reality often keep their elections carefully orchestrated. In other countries, like Libya, elections remain elusive after years of instability.

However, new movements are emerging. In 2019, widespread political protests in Algeria, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, and Sudan, signaled to authoritarian rulers their power could still be tenuous. In 2022, after the death of a 22-year-old woman reportedly beaten by police, protests also swept across Iran—challenging discriminatory laws against women and calling for democracy and freedoms. And in 2023, facing violence from their own government, protesters took to the war-torn streets of Syria, demanding an end to Bashar al-Assad’s brutal regime.

While many of these voices continue to be violently suppressed, they underscore the complexity of a region so often characterized by its lack of political freedom.

So how does the region look today? Here are ten political trends and dynamics impacting the Middle East and North Africa—and how they affect national politics in individual countries.

1. Oman: Absolute Monarchs Hold Power

While the region remains primarily ruled by authoritarians, regimes come in different shapes and sizes. In Iran, theocrats—religious political leaders—stand atop the government. In countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Oman, monarchs, sultans and sheikhs have ruled for decades, often passing along power from father to son. Oman is one interesting case: the country is ruled by a Sultan (currently Haitham bin Tariq Al Said). The structure of the Sultanate is similar to a monarchy: absolute rule passes in hereditary succession to the next of kin. The Sultan has absolute authority to enact laws through royal decree, and ministries have authority to issue rules and regulations. The country’s bicameral government includes an appointed arm (Majlis al-Dawla) and an elected arm (Majlis al-Shura). The last elections were held in 2023. With a 66 percent turnout, they re-elected the same chairman as previous years, and no woman was elected.

2. Saudi Arabia: Crackdown on Press Freedom

One way authoritarian regimes maintain power is by controlling the flow of information. This begins with limiting the role of the press: barring foreign journalists from entering the country, shutting down independent newspapers and websites, and propping up state-run media outlets to promote official narratives. Governments have even cracked down on social media websites, imprisoning users for any content deemed a threat to national security. Scores of journalists are in prison across the Middle East; Egypt and Saudi Arabia, notably, are the region’s two worst offenders. Saudi Arabia’s violence toward journalists made headlines around the world in late 2018 when Saudi critic and Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi was brutally killed inside the Saudi consulate in Turkey. Saudi Arabia claims the killing was done by “rogue agents.” U.S. intelligence believes Saudi Arabia’s crown prince ordered the killing, though he has since been given immunity. Since the killing, crackdowns on speech continue. In July 2023, a Saudi court sentenced a retired teacher to death for social media posts criticizing the country’s human rights violations.

3. Iran: Suppression of Political Dissent

So what happens to those who speak out and question their ruler’s authority? Many governments in the region use a highly feared secret police—such as the Guidance Patrol in Iran—to arrest who they want, when they want, and in the complete absence of civil liberties. Highly sophisticated surveillance technology is used to constantly monitor entire populations and crack down on any dissent. In Egypt and Iran, tens of thousands of prisoners are currently behind bars due to their political positions. Still, the arrests haven’t stopped protesters. Iran has seen a recent spate of protests following the death of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old woman beaten and arrested for violating the country’s mandatory hijab law. Iranian officials met the ensuing protests with force, killing more than 500 protestors and arresting over 22,000. Many voters then boycotted Iran’s 2024 parliamentary election, which barred reform candidates. The boycott has become its own act of political speech, signaling widespread dissatisfaction with the country’s rule.

4. Tunisia: March Toward Democracy

Authoritarian rulers in the region are not always able to hold on to power. Following the 2011 Arab uprisings, one country—Tunisia—successfully transitioned from authoritarianism to democracy. After ousting their longtime dictator, Ben Ali, Tunisia implemented presidential elections and power-sharing agreements between the country’s secular and Islamist parties. Since then, Tunisia has gone through nearly a dozen major government reshuffles, and the same economic factors that first brought citizens out in protests still present major challenges. New demonstrations broke out in 2018 over the country’s worsening inflation, unemployment rates, and gross domestic product (GDP), threatening to undo Tunisia’s fragile political gains. Politically, Tunisia has now seen worrying democratic backsliding. In 2022, Tunisia’s new president, Kais Saied, drafted a constitution that expanded his power and weakened the country’s parliament. In 2023, Tunisian authorities began arresting opposition politicians and journalists. Experts worry Tunisia may be sliding back into authoritarianism—a move that would undermine the Arab uprising’s biggest success story.

5. Egypt: The Failed Promise of Revolution

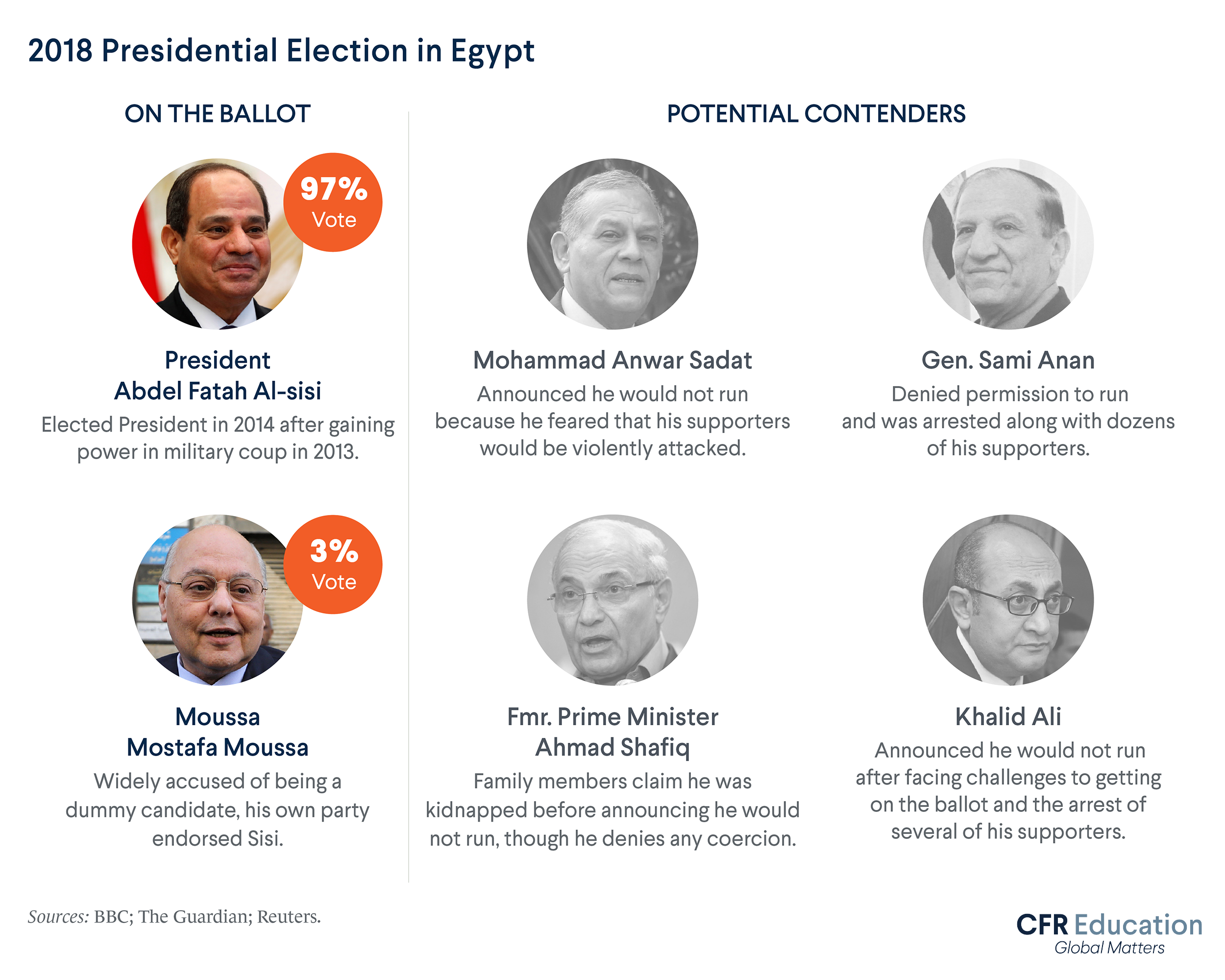

If Tunisia was the Arab Spring’s success story, Egypt was its tragedy. Egypt is the Middle East’s largest country, and it holds such tremendous cultural clout that it’s often referred to as Umm al-Dunya, or “Mother of the World.” So when more than a million Egyptians toppled their decades-long ruler in 2011, they set an example for the region, demonstrating that authoritarianism could be overthrown. The country went on to elect its first democratic president. But soon discontent began to grow—over the country’s plummeting economy, the encroaching role of Islam in government, and even mass fuel shortages. Just one year later, revolution returned to Egypt as the military overthrew the government. In Egypt’s 2018 presidential election, the incumbent General Abdel Fatah al-Sisi imprisoned, intimidated, or barred every legitimate political opponent from running against him. Unsurprisingly, Sisi won reelection with 97 percent of the vote. In December 2023, al-Sisi triumphed once more, this time in an election that once again saw arrests and political intimidation. The government continues to wield authoritarian power, detaining protesters and political opponents.

6. Syria: The Toll of Civil War

In three countries—Libya, Syria, and Yemen—Arab uprising protests ultimately devolved into civil war. The worst violence has occurred in Syria, where citizens protested against Bashar al-Assad, an oppressive, authoritarian president whose family has ruled Syria for five decades. The Assad regime began indiscriminately firing on peaceful protesters in 2011. Within a year, opponents started taking up arms. They included a disparate patchwork of moderate and extremist groups, like one new group, the self-proclaimed Islamic State, sometimes known as ISIS. Groups fought to unseat the Assad regime and implement their competing visions for the future of Syria. The Syrian civil war has left hundreds of thousands dead, with the Assad regime responsible for the overwhelming majority of those casualties—in some cases by using chemical weapons. For years, the Assad regime—with support from Iran, Russia, and the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah—had largely contained the opposition to parts of northwestern Syria. But in 2024, the regime fell after a surprise offensive from rebel forces. Enormous challenges remain concerning reconstruction, the return of millions of refugees and displaced people, and the security of a country reeling from one of the most destructive conflicts in modern history.

7. Yemen: The Toll of Humanitarian Crisis

Over the past decade, wars in Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen have resulted in tremendous loss of life. These conflicts are so deadly not only from the violence, but also because of the humanitarian crises that result when civilians lose access to food, medicine, and shelter. Yemen, for example, is experiencing one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises as a result of the ongoing civil war between Iranian-backed Houthi rebels and the Saudi-backed Yemeni government. The civil war began in 2014 after the overthrow of the government. Since then, nearly 400,000 people have died as a result of violence and famine, according to the UN. Global events have also made the situation worse. Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine disrupted global supplies of wheat, worsening famine conditions. Meanwhile, the Saudi-led coalition’s naval and air blockade has prevented humanitarian aid from entering the country; Iranian-backed rebels also participate in blockades. As a result, an estimated 17 million Yemenis (roughly half of the country’s population) are now at risk of food insecurity; six million Yemenis are facing famine.

8. Jordan: Mixed Signals on Reform

While some countries in the region violently block political reform, Jordan has been a little different. Few Jordanians report having trust in their parliament, which generally serves the interest of King Abdullah II, the ruling monarch. Despite these issues, the country has hosted cycles of reform since at least 1989. These cycles follow similar patterns. (Instability or public outcry leads to the establishment of reform committees. Proposals for modernization follow. But then ultimately few things get changed.) One recent cycle began in 2021, after King Abdullah II’s half brother was accused of plotting a coup. In response, a new electoral law was announced in 2022. The law attempts to diversify the country’s parliament, designating seats for women and minority groups. Critics have claimed these laws won’t fundamentally challenge current ruling groups. And many Jordanians have other concerns. With high unemployment and increased persecution of political dissent, it’s likely Jordan will watch another reform cycle pass without substantial political change. Still, Jordan’s continued flirtation with reform has made others cautiously optimistic about the country’s political future.

9. Lebanon: Religious Diversity in Government

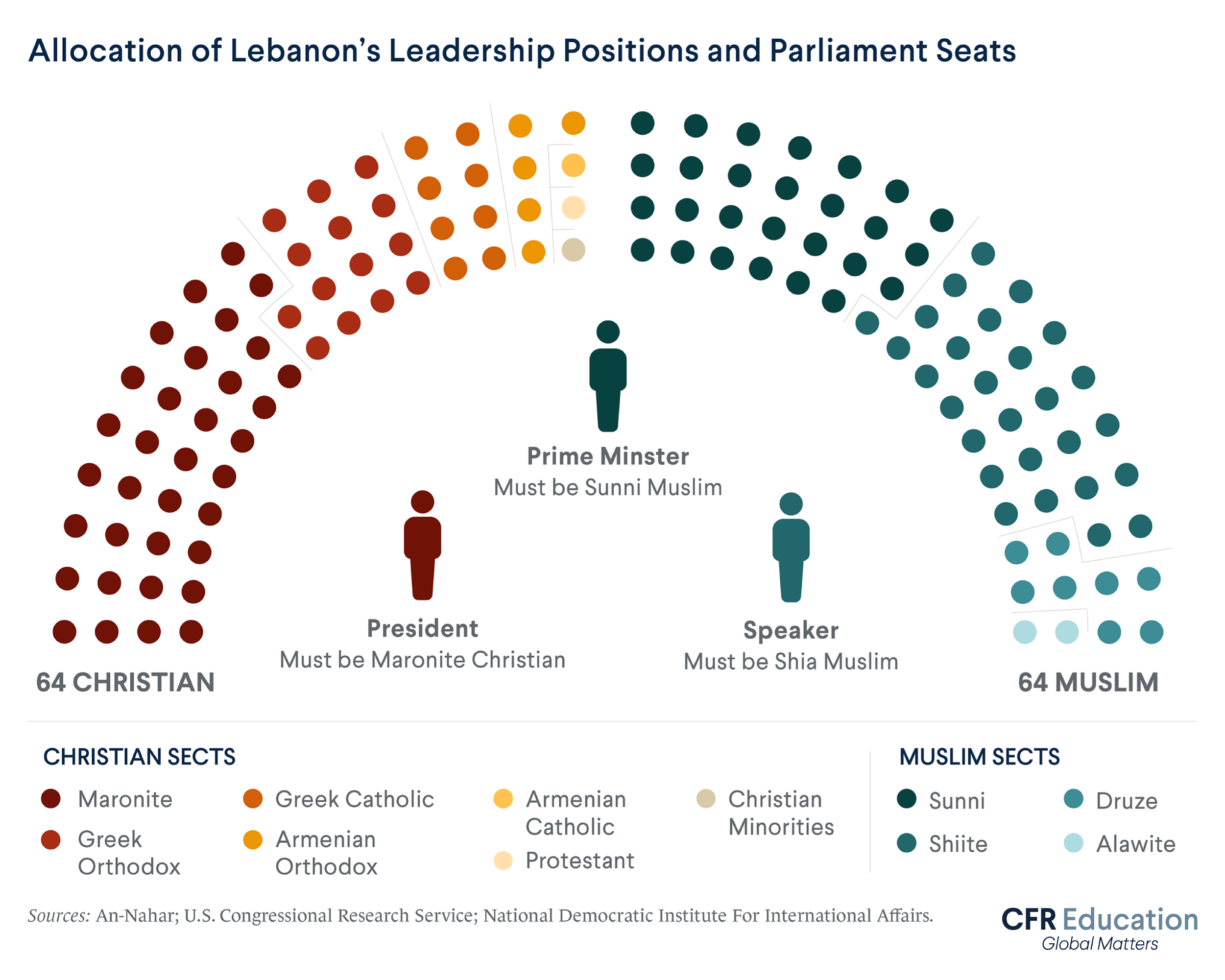

Kings, sheikhs, and generals rule the majority of the Middle East, but the small Mediterranean country of Lebanon adopted an alternative system: a semi-democratic government with political representation apportioned along religious lines. In this system, known as confessionalism, the president of Lebanon must be from a Christian denomination known as the Maronites, the prime minister must be a Sunni Muslim, the speaker of parliament a Shiite Muslim, and the seats of parliament divided evenly between Christians and Muslims. These allocations are almost entirely based on the country’s last census, taken in 1932. Leaders have avoided conducting another census because some religious groups fear the census will reveal their share of the population has declined. In recent years, other events have instead threatened the country’s political stability. Since 2019, high inflation has contributed to an ongoing economic crisis. Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine has raised food prices. And now military hostilities between Israel and Hezbollah threaten national security. In October 2024, Israel commenced a ground invasion against Hezbollah in southern Lebanon and launched strikes that killed the group’s longtime leader, Hassan Nasrallah. Despite Nasrallah’s death, conflict continues and fears of further escalation remain, adding to the country’s uncertain economic and political future.

10. Israel: Rightward Shift

The Middle East now faces further destabilization. On October 7, 2023, Hamas attacked Israel, killing Israeli civilians. Israel’s response to these attacks has included an aggressive military campaign in Gaza, which has killed tens of thousands of civilians. That military decision-making has been shaped by an evolving trend in Israeli politics, one that favors confrontation over negotiation. Over the past twenty-five years, and following the collapse of the Israeli-Palestinian peace process in the 1990s, Israel’s politics have shifted sharply to the right. This shift has brought previously fringe positions into the political mainstream; for example, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu formed his 2022 government by joining with ultranationalist parties committed to expanding Israel’s settlements in the West Bank. Right-wing support among young Israeli voters is also growing, shaped also by the fallout from the recent October 7 attacks. As conflict in the region escalates, Israeli’s leaders and their politics may determine the future of Middle East relations.