Modern History and U.S. Foreign Policy: Middle East and North Africa

From the fall of the Ottoman Empire to U.S. efforts to advance Arab-Israeli partnerships, learn how history and foreign influence have shaped the region.

The Middle East, sometimes referred to as the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), is home to great historical civilizations. Driving groundbreaking advances in astronomy, mathematics, and philosophy, the regional capital of Baghdad became a center of learning where scholars translated Aristotle and invented algebra. Meanwhile, empires expanded across the region. In the twelfth century, Muslim empires controlled territory spanning from modern-day Iran to Spain. During the thirteenth century, an ethnically Turkish tribe began a campaign of conquests that gave rise to the Ottoman Empire. For centuries, the Ottomans controlled almost the entire Middle East and parts of North Africa— territory as far as the gates of Vienna in central Europe.

The region has also long been shaped by foreign influence. Its modern borders began to take shape in the early twentieth century after the Ottoman Empire collapsed. While vast empires no longer rule over the region, both international and regional competition among powers continues to define the Middle East’s modern history.

For more than half a century, the United States played a prominent role in the Middle East. It has imparted political, military and economic influence to advance its foreign policy priorities in the region. These have included defending Israel, ensuring the free flow of oil, and - during the Cold War - limiting the influence of the Soviet Union.

But today, the United States’ interests in the region—and influence—are shifting. Israel is no longer a vulnerable country but rather a military heavyweight that has been strengthening relations with former rivals like Saudi Arabia and Egypt. The United States no longer relies on Middle Eastern oil. It’s now a net energy exporter through its own oil and gas production. Meanwhile, the American people grew war-weary following failures in the Iraq War, which killed hundreds of thousands of civilians and undermined U.S. credibility in the region. A rise in Chinese investments in the region is also shifting the landscape.

Despite the U.S. drawdown from its active military presence in Iraq and Afghanistan, renewed conflicts may once again pull in old powers. With conflict escalating between Israel, Hamas, Hezbollah and Iran, experts fear that one sudden misstep could draw the United States back into another costly confrontation.

Here are some of the critical moments in the region’s trajectory, and the role of U.S. foreign policy within it, since the start of the twentieth century.

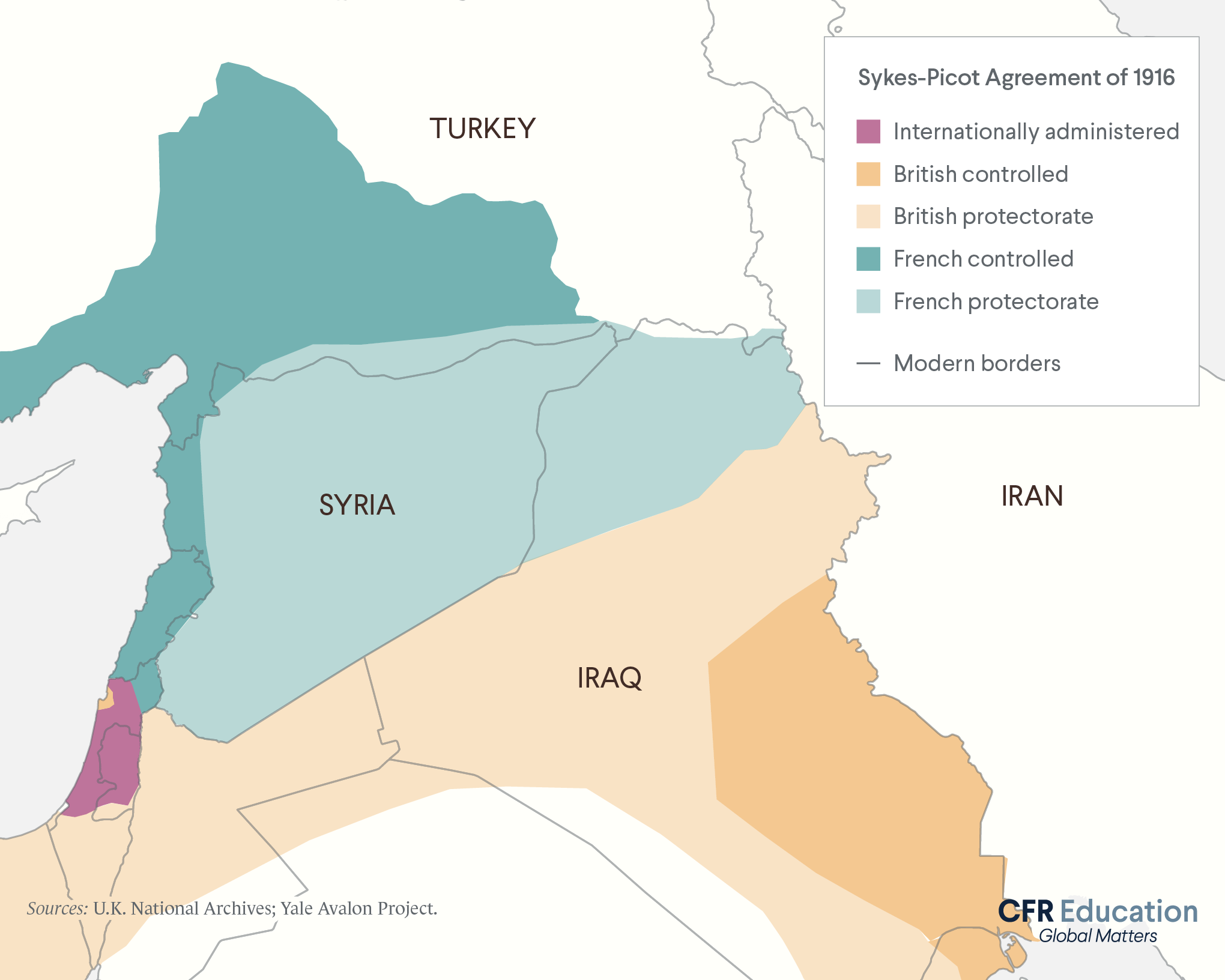

1916

Ottoman Empire Falls, Europe Redraws Borders

For hundreds of years, the Ottoman Empire controlled much of the modern Middle East. This powerful empire collapsed after the Ottomans fought on the losing side of World War I. The war’s victors, England and France, then took over. Beginning with the Sykes-Picot Agreement in 1916 and continuing through a series of later treaties, the British and French carved up Ottoman lands for themselves. They drew borders in the Middle East that supported their own goals—such as access to trade routes—with little regard for those living in the region. The modern borders of Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Turkey remain largely the same as those the British and French drew a century ago. To this day, those border decisions divide people with common histories and shared identities. Some borders also unite diverse ethnic and religious groups, contributing to sometimes fragile national identities in the region.

1938

Saudi Arabia Discovers Oil, Attracting the United States

King Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud conquered the Arabian Peninsula and established the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932. Ibn Saud owed much of his rise to military and political support from the fundamentalist Wahhabi movement, which follows a strict interpretation of Islam. The alliance between the Saud family and Wahhabi clerics continues to this day. But it was Saudi Arabia’s discovery of oil in 1938 that boosted the young country’s power. Oil brought the Kingdom immediately into contact with the United States. Toward the end of World War II, U.S. energy experts feared American oil fields would run out. Securing new oil abroad became a national security priority. As a result, President Franklin D. Roosevelt began to pursue closer relations with Ibn Saud. The two leaders met in February 1945, marking an important start to a bilateral relationship that continues to this day.

1948

Israel Declares U.S.-backed Independence

In 1917, the British, who had taken control of Palestine following the fall of Ottoman rule, announced their support for building a Jewish home in Palestine. People known as Zionists—members of a national movement to establish a Jewish state in their biblical homeland—supported Jewish immigration. They also bought local property, sparking tensions with Arab farmers living there. In 1947, following World War II and the horrors of the Holocaust, the United Nations announced that Palestine would be partitioned into separate Jewish and Arab countries. Once the British left, Jewish leaders declared independence. Arabs, however, rejected the UN partition, which—in their view—seized their ancestral lands. War soon broke out in what is widely referred to as the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. While Israelis refer to this conflict as their War of Independence, Arabs know it as the nakba (Arabic for “catastrophe”), since it forced hundreds of thousands of Palestinians to flee their homes. The United States supported Israel’s independence for moral, political, and strategic reasons. They also believed backing this young democracy would prevent the Soviet Union and communism from gaining a foothold in the region.

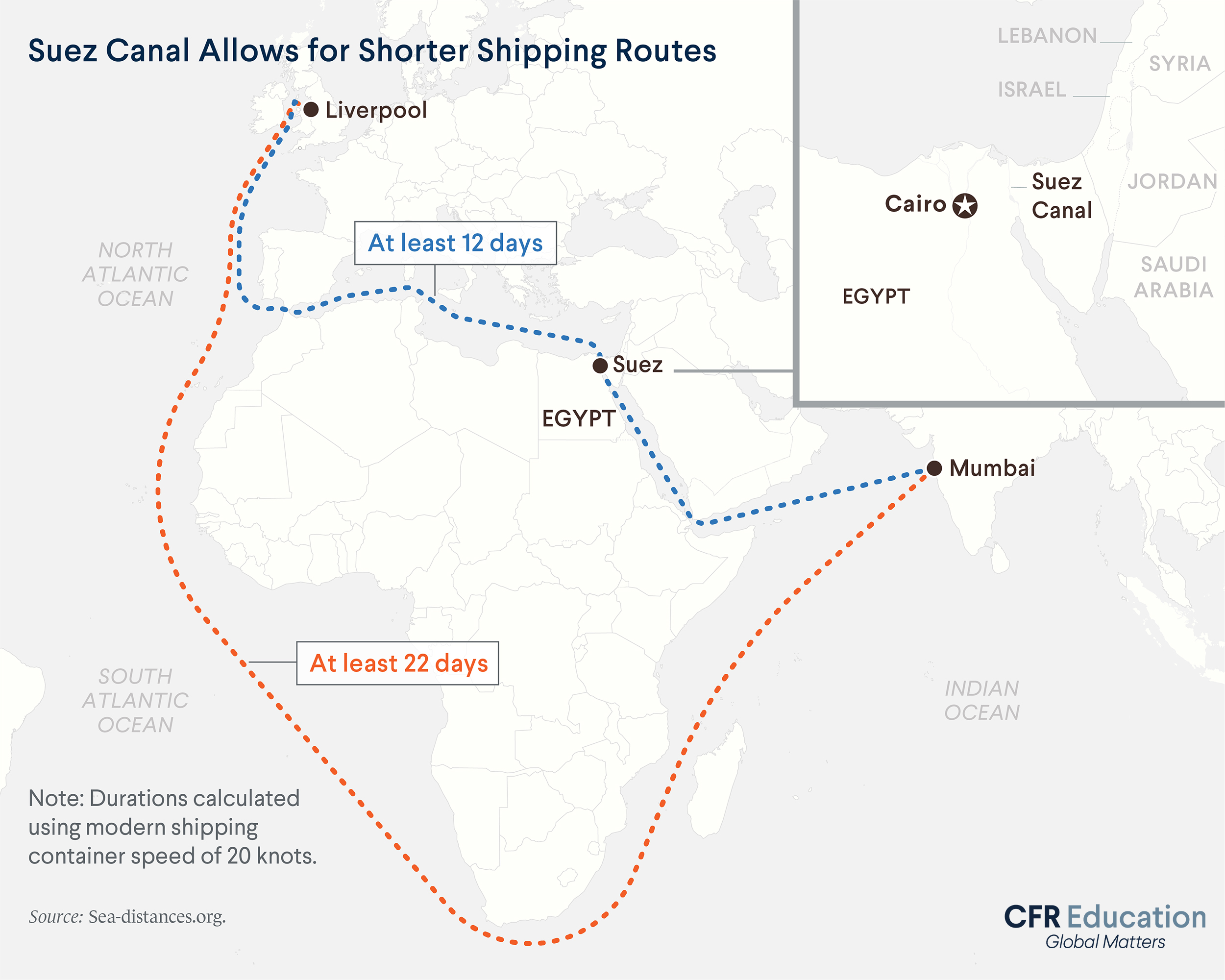

1956

Egypt Claims the Suez Canal, Changing Regional Politics

In the early twentieth century, Britain and France jointly managed the Suez Canal. This crucial waterway in Egypt connects the Mediterranean Sea to the Indian Ocean. But in 1956, Egypt’s charismatic leader, the anti-imperialist Gamal Abdel Nasser, announced his country would take over (“nationalize”) the canal. In response, Britain and France—along with Israel, which viewed Nasser as a potentially powerful enemy—invaded Egypt. The United States strongly opposed the invasion, worrying it would push Egypt closer to the Soviet Union and Communism. Instead, the United States forced Britain and France to withdraw from Egypt. The conflict changed the balance of power in the Middle East. After a ceasefire, Israel became even more alienated from its Arab neighbors. Nasser’s Egypt became a leader in the Arab world for resisting the invading forces. And Britain and France lost the canal and much of their remaining influence in the region. In their place, the United States emerged as the Middle East’s preeminent foreign actor.

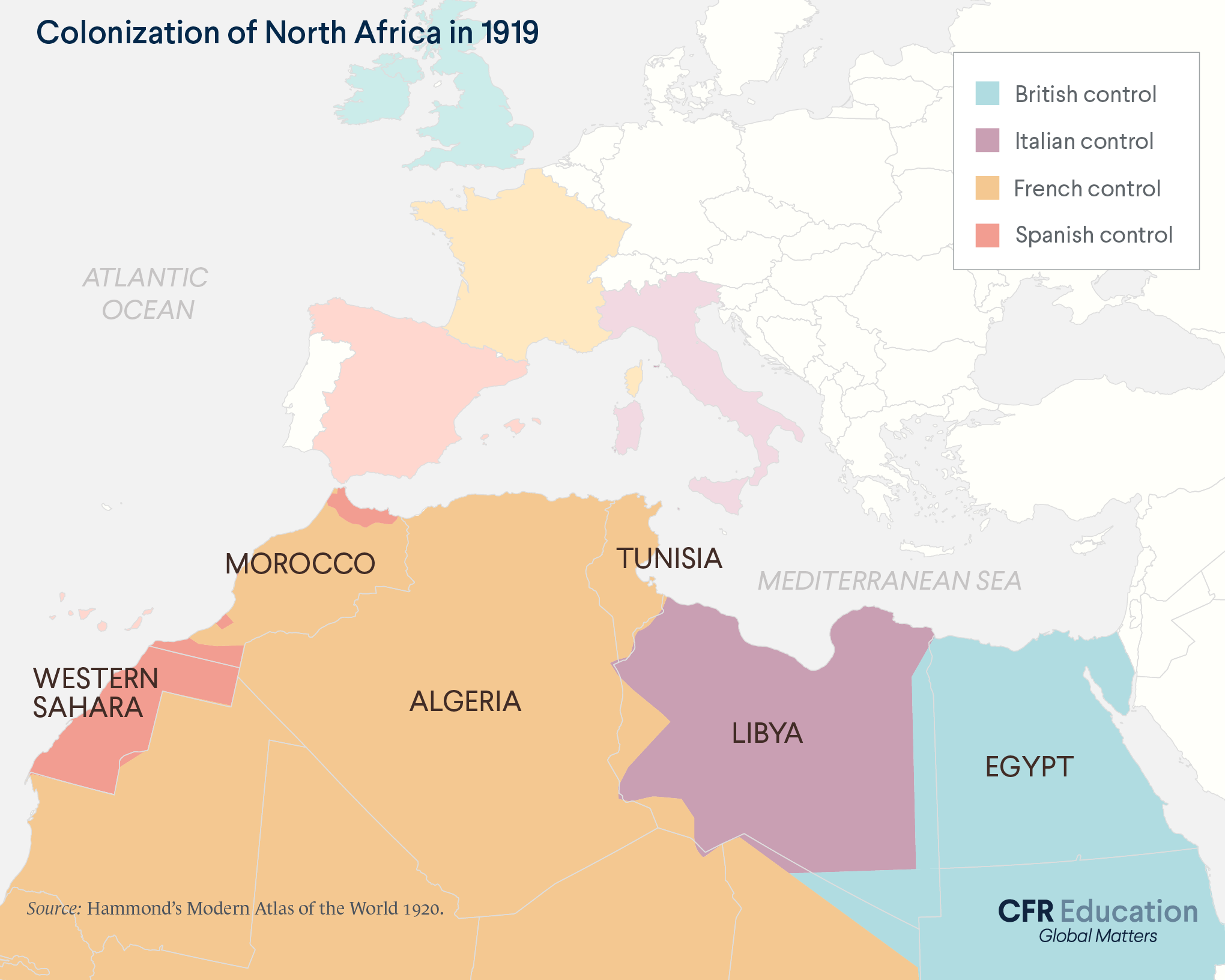

1951 – 1962

North African States Challenge Colonial Rule

During the 20th Century, North Africa experienced decades of European colonization. Italy controlled Libya from 1911 to 1947, using chemical weapons against local resistance movements and imprisoning their members in concentration camps. Spain controlled colonies in parts of modern-day Morocco. France controlled other parts of Morocco as well as modern-day Tunisia and Algeria—where hundreds of thousands of French people settled, seizing land and depriving Algerians of their rights, often violently. Libya finally gained independence in 1951 following Italy’s defeat in World War II. Spain relinquished most territory in 1956 and 1958, after a brief and deadly war with Moroccan insurgents. But Algeria’s fight was longer and even bloodier. Opposition to French colonization erupted in 1954 in the Algerian War of Independence, leaving hundreds of thousands dead and millions more displaced. The war ended in 1962 with an independent Algeria. However, colonial independence didn’t mean a complete withdrawal of European powers from the region. Spain still governs two port cities in North Africa to this day.

1967

Six Day War Redraws Borders Once Again

Israel has worried about its security since its founding. By 1967, Israel had already fought two wars—one with its Arab neighbors immediately following the country’s establishment in 1948 and one against Egypt in 1956. Israelis feared that a third conflict was imminent. Egypt’s then President Gamal Abdel Nasser repeatedly promised to avenge displaced Palestinians and was parading troops and tanks through the streets of Cairo. In response, Israel launched a preemptive attack against its Arab neighbors on June 5, 1967. These strikes destroyed the air forces of Egypt, Jordan, and Syria, paving the way for rapid Israeli ground advances. By June 10, the land Israel controlled had tripled in size, as it took over Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula to the banks of the Suez Canal, Syria’s Golan Heights, and the territories of East Jerusalem, the Gaza Strip, and the West Bank. Known as the Six Day War, this conflict redrew borders within the Middle East, establishing Israel as the region’s dominant military power. The war also dealt a devastating blow to Arab armies and exacerbated the numbers and plight of Palestinian refugees.

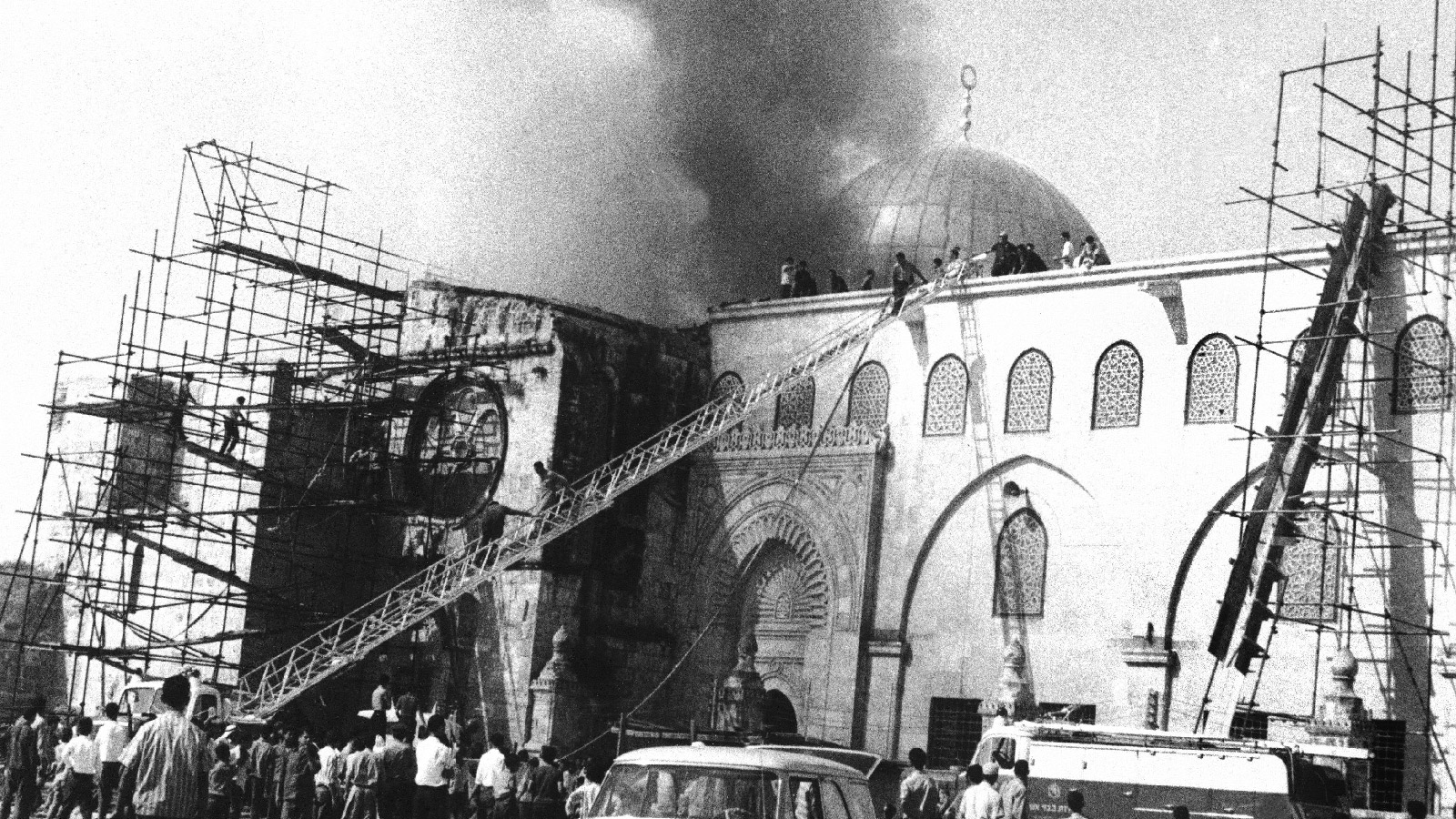

1969

Al Aqsa Burning Unites Muslim World

The al-Aqsa Mosque, located in East Jerusalem, is considered one of the most sacred mosques in Islam. After the Six Day War, Israel occupied all of Jerusalem, despite U.N. criticisms. In August 1969, an Australian Christian fundamentalist set multiple kerosene fires inside the mosque. Muslims across the region and the world were outraged by the arson and Israel’s investigation into the crime. Many blamed Israel itself for the arson. Some called for an uprising or war to liberate al-Aqsa from Israeli control. The mosque burning galvanized Muslim countries, but the Muslim world lacked a collective body to organize and take action on issues like the political status of Jerusalem. The fire catalyzed a strong sense of unity, and a month later Muslim countries founded the Organization of Islamic Corporation (OIC), a collective voice for Muslims living around the world. Today the OIC includes 57 members and is the largest organization of Muslim countries.

1973

Yom Kippur War Leads to U.S.-backed Deal

In October 1973, Egypt and Syria prepared to attack Israel once again, this time in a bid to reclaim territory lost during the Six Day War. The Arab armies surprised Israel by invading on Yom Kippur, the holiest Jewish day. Though the Soviet-armed Arab coalition initially breached Israel’s defenses, Israel—with U.S. military aid—eventually managed to counter the Egyptian and Syrian armies. With fighting reaching a fever pitch, the United States and Soviet Union resolved to de-escalate the situation. The armies signed a ceasefire agreement. Following the war, the United States brokered a series of further agreements. These negotiations culminated in the 1978 Camp David Accords, as a result of which Israel agreed to withdraw from previously taken Egyptian territory. The United States wanted to respect Israel’s security concerns while also improving relations with Arab oil producers (notably Saudi Arabia), which had opposed U.S. actions during the war. For decades, U.S. administrations have sought to replicate the success at Camp David. However, despite some progress in recent years towards normalization of Arab-Israeli relations, many Arab countries do not hold formal diplomatic relations with Israel.

1979

Revolution Turns Iran From U.S. Friend to Foe

A father-son dynasty known as the Pahlavis ruled Iran from 1925 to 1979. The Pahlavis were modernizers who promoted industrialization and women’s rights. They were also unelected strongmen who violently suppressed political dissent. But the rulers were U.S. allies. They delivered valuable oil rights to the United States and Britain in exchange for weapons and political support. (The CIA even backed a 1953 coup in Iran that overthrew a democratically elected prime minister in order to keep the Pahlavis in power.) Most Iranians saw the monarchy as a corrupt American puppet. Frustration with the Pahlavis culminated in the 1979 Islamic Revolution, which toppled the monarchy and brought a fiercely anti-Western government to power. The new ruler was Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a formerly exiled cleric who opposed American interests. Soon after the revolution, Iranian university students stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, taking American staff hostage for 444 days. The crisis resulted not only in American sanctions on Iran but also the severing of diplomatic relations, which remain suspended more than four decades later.

1980

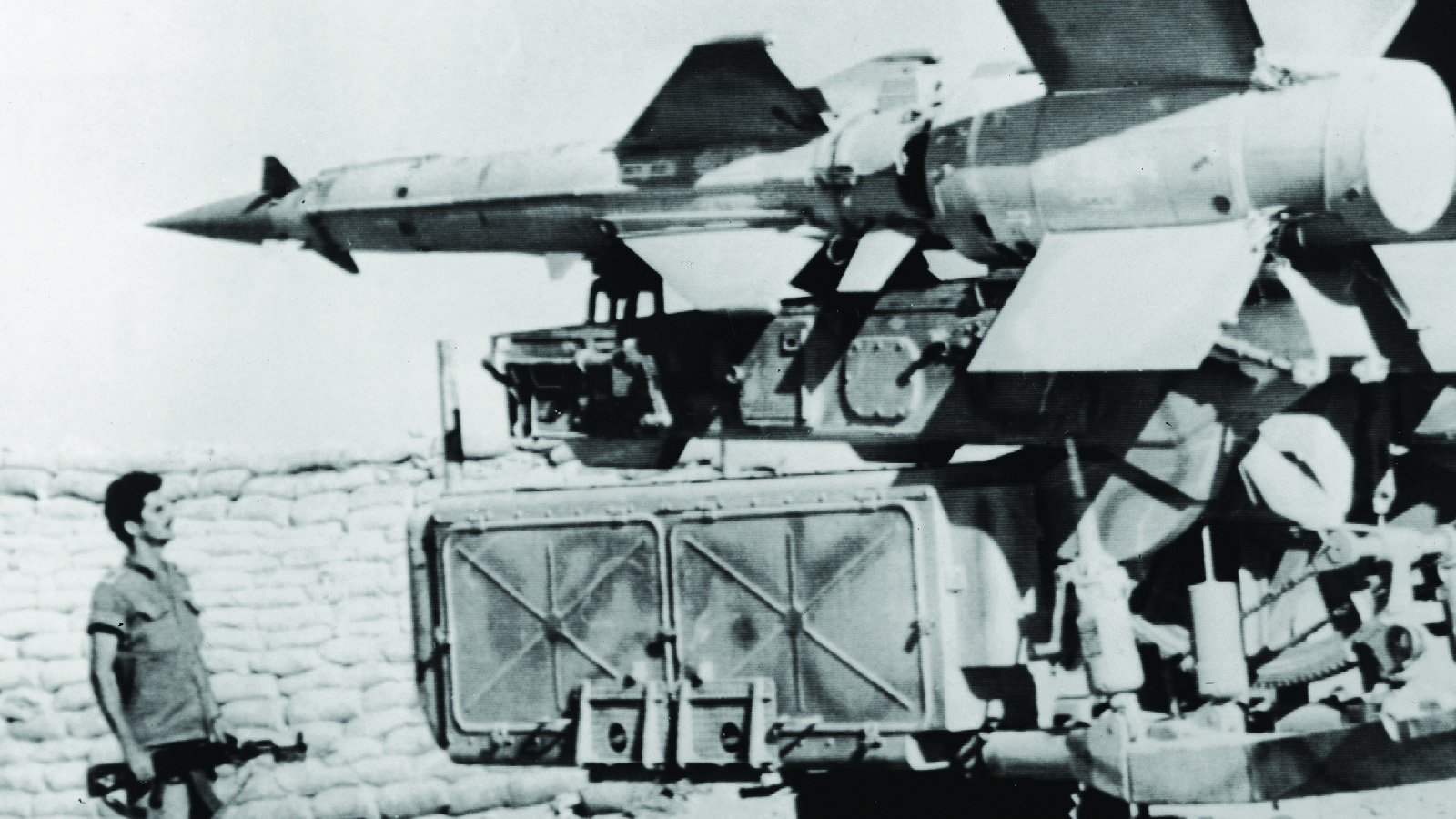

Iraq Invades Iran

After its revolution, Iran sought to extend its influence to the Middle Eastern heartland. Its government supported politicians and armed groups that followed its sect of Islam (Shiism), often frustrating many of Iran’s Arab and Sunni neighbors. One neighbor, Iraq, quickly hit back. Saddam Hussein, Iraq’s dictatorial ruler, saw revolutionary Iran as a threat, worrying the country would seek to destabilize Iraq and his ruling Sunni-dominated party. Without the United States supporting Iran, Saddam saw his chance and launched an invasion. The military operation was a failure. Iran quickly retook territory and the armies reached a stalemate. Bloody fighting continued for eight years, during which Saddam’s military used chemical weapons against Iranian soldiers and Kurdish civilians. The United States alternately provided military support for both Iraq (to counter Iran as a new U.S. adversary) and Iran (in exchange for hostage releases and because the United States feared expanding Soviet influence in Iran). This double-sided support ultimately prolonged the war and further destabilized the region. The war ended in stalemate with half a million lives lost, and regional sectarian divisions between Sunnis and Shias widened for years to come.

1990

Iraq Invades Kuwait, the United States Responds

In 1990, seeking to seize oil reserves, Iraq invaded Kuwait. The invasion prompted immediate international outrage; the United Nations demanded that Iraq withdraw. When it refused, the United States led an international coalition to liberate Kuwait. U.S. President George H.W. Bush worried that Iraqi President Saddam Hussein might invade Saudi Arabia next. If that happened, it would risk giving an unpredictable dictator control over much of the world’s oil supply. Bush also believed Iraq posed a risk to Israel’s security, given its threats to use chemical weapons against the Jewish country. Additionally, he acted to defend the principle of sovereignty—that no country’s territory could be taken by force. Ultimately, more than five hundred thousand American troops fought in the Gulf War, leading to a swift defeat of Iraqi forces. But after liberating Kuwait, coalition forces decided not to push into Iraq’s capital, Baghdad, to depose its dictator. It would be another decade before U.S. troops returned to undertake that mission.

1993 – 2000

Oslo Accords Broker Fragile Peace

After decades of war, occupation, and mutual mistrust, authorities from Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO)—the official representative of Palestine— met to negotiate. The talks began with the 1991 Madrid Conference. They continued with a set of agreements facilitated by Norway in 1993 known as the Oslo Accords. The accords outlined a possible two-state solution intended to provide lasting Israeli security in exchange for an independent Palestine. The agreements did not resolve some of the conflict’s toughest challenges—such as addressing borders, sovereignty, Palestinian refugees, and control of Jerusalem—but they marked progress by bringing the conflicting parties to the table, ultimately leading to the PLO’s recognition of the State of Israel. Still, optimism about future negotiations was short-lived: In 1995, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by a Jewish extremist. Benjamin Netanyahu became prime minister of Israel in 1996 and, despite being critical of the Oslo accords, initially worked to ease tensions between Israelis and Palestinians. But Israeli settlements expanded across Palestine, Palestinian attacks struck Israeli civilians, and deadlines laid out in the Oslo accords passed without progress. In 2000, the Palestinians launched an uprising (known as the Second Intifada) which dashed hopes for peace.

2001

9/11 Attacks Redefine U.S. Counterterrorism Strategy and Involvement in the Region

On September 11, 2001, militants from the terrorist group al-Qaeda hijacked four planes and used them as weapons to kill 2,977 people. In response, the U.S. Congress passed the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), which gave the president sweeping power to pursue the attacks’ perpetrators and their supporters. The AUMF, however, did not define a specific target or establish an end date for these broad new powers. As a result, this sixty-word authorization has been used to justify some of the United States’ most significant military and counterterrorism operations in the region and around the world for more than two decades, including the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan, air strikes against al-Qaeda affiliates in Somalia and Yemen, military action in Iraq and Syria against the self-proclaimed Islamic State (also known as ISIS), and even extensive surveillance of American citizens.

2003 – 2011

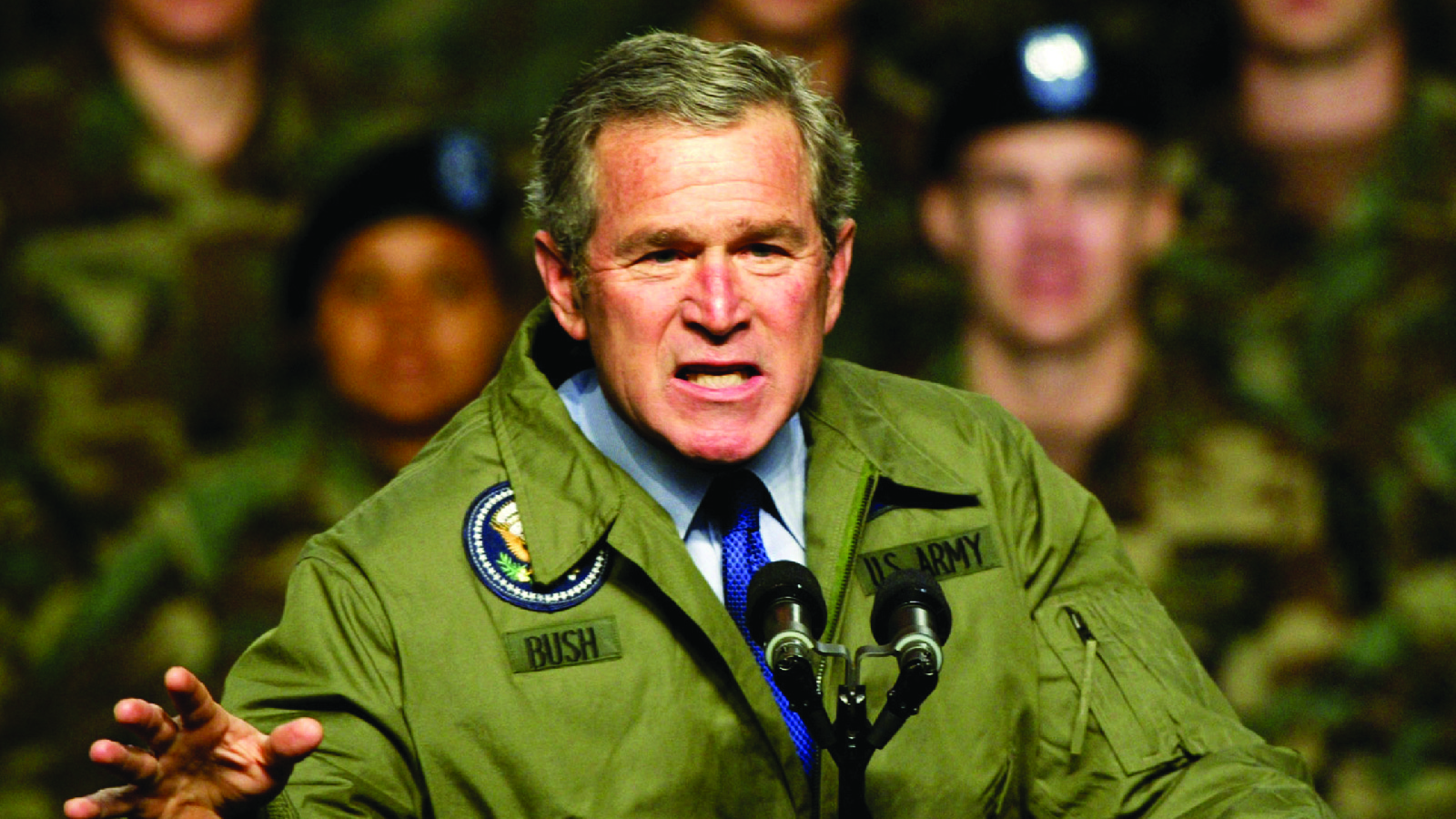

The United States Invades Iraq

In 2003, U.S. troops invaded Iraq. The George W. Bush administration argued that Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein was hiding weapons of mass destruction and would use them to threaten his neighbors. They also argued Iraq had connections to al-Qaeda, the terrorist group responsible for the 9/11 attacks, although these claims have since been debated and discredited. The Iraqi army was quickly defeated in the war. Saddam was ultimately captured, put on trial, and executed. But the United States failed to find weapons of mass destruction, or to plan for its subsequent occupation of Iraq. Those failures resulted in massive civil unrest, the rise of insurgent militias, and deadly conflict that killed over one hundred thousand civilians. After U.S. forces withdrew from Iraq in 2011, Iran has made use of the ensuing power vacuum to enhance its influence over Iraqi decision-making. Terrorist groups and Iran continue to obstruct the development of a stable Iraq and threaten the security of the country and the region.

2006 – 2007

Hamas and Hezbollah Challenge Israeli Might

Cycles of violence—marked by Palestinian rocket attacks and Israeli military retaliation—increased after the breakdown of peace agreements between Israel and Palestinian authorities. Meanwhile, the Palestinian economy struggled. In 2007, Hamas (a U.S.-designated terrorist organization) took control of the Palestinian territory of Gaza. In response, Gaza’s two neighbors—Egypt and Israel—imposed a near-total land and sea blockade. The blockade carried dramatic economic consequences for average civilians and effectively turned Gaza into an open-air prison. By 2023, more than half of Gazans lived in poverty, many in densely populated places lacking electricity, water supply and adequate healthcare. In defiance of Israel, Hamas leveraged the geographic position of the Gaza strip to periodically launch rocket attacks on Israeli towns and cities. To the north in Lebanon, another group was also increasing their attacks on Israel—Hezbollah, a political party and militant group. In 2006, Hezbollah (which the United States also designates a terrorist organization) abducted two Israeli soldiers, kicking off a month-long war.

2010

Arab Uprisings Seek to Topple Authoritarian Regimes

On December 17, 2010, a Tunisian street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire to protest government corruption and abuse. This act sparked protests across the region. Millions took to the streets demanding political, economic, and social reforms from their own governments—all of whom had been historically unresponsive to their needs. Such civil disobedience had been extremely rare in these countries where authoritarian leaders forbade political dissent. The protests (collectively referred to as the Arab uprisings, sometimes also known as the Arab Spring) took different trajectories. Tunisia successfully transitioned from authoritarianism to a fragile democracy. Egypt held its first democratic presidential elections in 2012. However, only one year later, a counterrevolution returned the country to military rule. Today—over a decade after the first Arab uprisings—most ruling power structures remain in place and few reforms have actually taken root. Nevertheless, new protests broke out in 2019 in Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Sudan, signaling the enduring legacy of the Arab spring in regional politics.

2011 – 2013

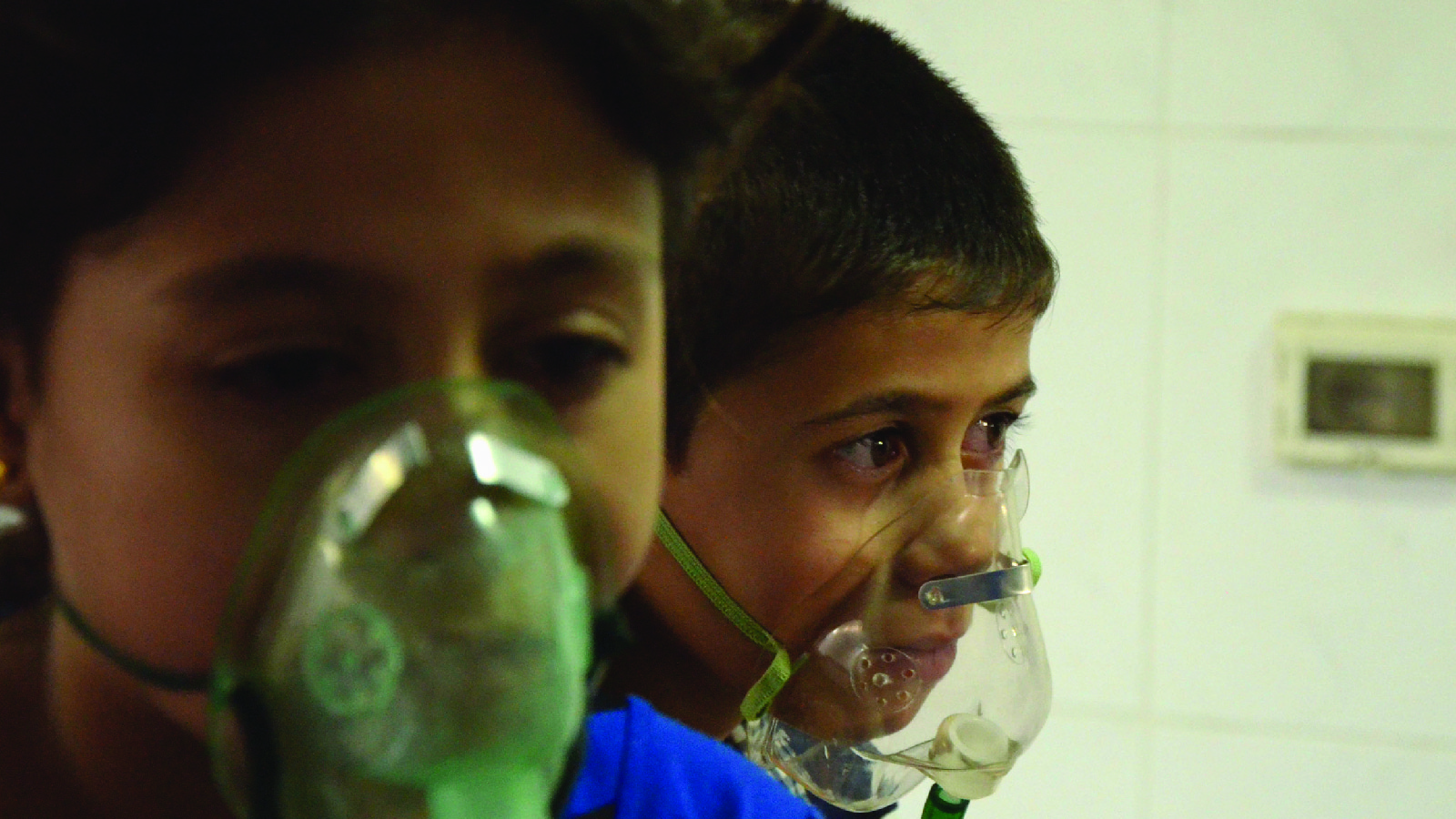

The United States Intervenes in Libya, but not Syria

The Arab Uprisings ushered in a year of hope—but also one of great violence and instability. In Tunisia, where the movement began, the country held elections for the first time since their independence from France in 1956. But other countries soon spiraled into civil war. In Libya, the country’s dictator, Muammar al-Qaddafi, threatened to kill protesters en masse. U.S. President Barack Obama, together led a coalition of North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) members that aimed to protect Libyan citizens. The coalition’s efforts ultimately enabled rebel forces to capture and kill Qaddafi. This infuriated Russia and China, who criticized the intervention as an overreaching act of interference in a sovereign country. Russian and Chinese opposition undermined international support for future humanitarian interventions—including in Syria, where peaceful protests turned to violence in 2011. Here, the U.S. supplied limited weapons and training to rebels who opposed Syria’s oppressive ruler Bashar al-Assad. It wasn’t enough. Even when Assad gassed thousands of civilians later in 2013, the United States refused to intervene. The decision further undermined U.S. credibility among its friends and allies. Assad would go on to kill hundreds of thousands of civilians in a war that has displaced more than half of the country’s pre-war population.

2014 – 2018

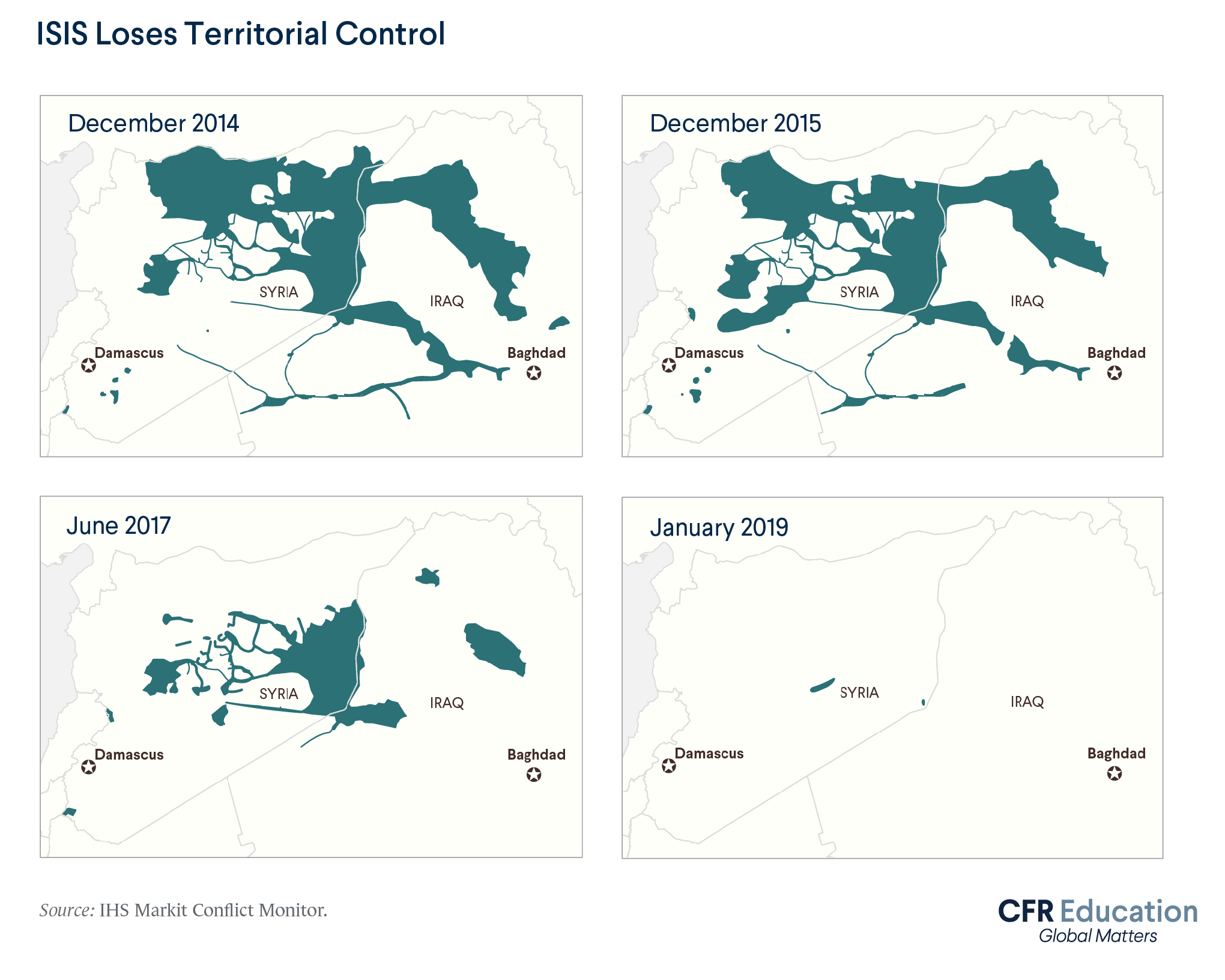

Regional Forces Unite to Eliminate the Islamic State

The United States withdrew its forces from Iraq in 2011. In the aftermath, the country was left fractured by sectarian violence. One dominant group emerged: the Islamic State. Originally part of al Qaeda in Iraq, the Islamic State seized territory in both Iraq and Syria. The group imposed a brutal form of Islamic law in its territory. The Islamic State also launched attacks outside its borders, including the November 2015 attacks on Paris that killed over 100 people. In response to the Islamic State’s rise, the United States began a series of air strikes and also started training and equipping local forces to combat the group. These included the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-Arab militia. In Iraq, state security forces as well as Kurdish forces also fought to retake territory claimed by the Islamic State. In March 2019 after years of intense fighting, the SDF announced the final destruction of the Islamic State. Although the group no longer holds territory, it continues to launch attacks in Syria and Iraq. Islamic State-affiliated groups have also launched attacks in Oman, Russia, Iran, and other countries.

2015

The United States Shifts Tactics with Iran

The United States has long opposed Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons. It is opposed to the threat an Iranian bomb poses to U.S. ally Israel, and its potential to spur a nuclear arms race in the region. In 2015, Iran was only months away from developing this weapon. The United States, along with five other countries, negotiated and signed a deal with Iran known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in July 2015. The controversial deal lifted international sanctions on Iran in exchange for a fifteen-year limit on Iran’s nuclear program. Opponents of the deal claimed it did not do enough. In 2018, U.S. President Donald J. Trump withdrew the United States from the JCPOA, reinstating sanctions on Iran. In response, Iran has once again begun producing enriched uranium, which is needed to create an atomic bomb. In 2024, U.S. officials warned that Iran has the capability to produce enough materials for nuclear weapons in a timeframe of about two-weeks—the shortest window, often called “breakout time,” ever acknowledged by the United States.

2018

U.S.-Saudi Relations Grow Despite Controversy

In October 2018, Saudi agents assassinated and dismembered Jamal Khashoggi, a U.S.-based Washington Post journalist, Saudi citizen, and critic of the Saudi government. For decades, Saudi Arabia has been one of the United States’ closest partners in the Middle East. Originally, U.S.-Saudi relations focused on oil and security cooperation. Today the two countries partner to counter terrorism and Iran’s expanding influence, backed by a controversial but ongoing supply of U.S. arms. However, this partnership has faced challenges in recent years, including the Khashoggi killing and Saudi Arabia’s highly controversial war in Yemen, where it has repeatedly bombed civilians. U.S.-based human rights activists have also long criticized the regime’s authoritarian governance and mistreatment of its citizens, including women who face gendered restrictions. But despite these human rights abuses, the United States sees Saudi Arabia as an increasingly important ally. Under U.S. President Joe Biden, the United States continued to push for normalization between Saudi Arabia and Israel, and remains Saudi Arabia’s largest trading partner.

2022

Women’s Rights Takes Center Stage in Iran

Since Iran’s 1979 revolution, the government has enforced strict rules on civic life. These include regulations on international travel, limits to media and internet access, and restrictions on protests. Women face some of the strictest discriminatory laws. These laws apply to everything from divorce and child custody to inheritance and dress code—where head coverings, or hijabs, are mandatory. Failure to follow these laws can result in imprisonment, fines, and lashes. In September 2022, and in the wake of increased enforcement, 22-year-old Mahsa Amini was arrested for dress violations. Amini was reportedly beaten in a police van; she later died in the hospital. Amini’s death sparked outrage and led to widespread protests. The Iranian government responded with force, arresting over 20,000 people and killing over 500 protesters. The movement, named “Woman, Life, Freedom,” continues to call for reform as well as accountability for the government’s brutal crackdown. Experts credit the movement with shifting patriarchal attitudes—as research suggests the majority of Iranians, both men and women, now support the protest movement. Two years later, however, government repression of women remains a part of life in Iran and security forces continue to crack down on any expressions of protest.

2023

Hamas Attacks Israel

On October 7, 2023, Hamas launched a cross border attack on Israel, targeting military installations and indiscriminately killing over 1,200 Israeli civilians. Hamas also took over 200 Israeli hostages. Ongoing U.S.-led efforts to normalize relations between Saudi Arabia and Israel angered many Palestinian leaders and Hamas was determined to bring attention to its demands in the region. Since October 7, Israel, supported by U.S. military technology, has sought to root out and eliminate Hamas. The resulting war has unfolded into a humanitarian crisis, causing more than 40,000 Palestinian deaths in the first year. The ensuing humanitarian crisis and Israel’s alleged targeting of civilians has been criticized by many countries and launched proceedings in both the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court. The war has also raised fears of escalation toward a wider regional war. Hezbollah and Iran have both launched rocket and missile attacks on Israel in response to its operations in Gaza. In October 2024, Israel commenced ground operations in Lebanon against Hezbollah.