The 1828 Jackson vs. Adams Election and Tariffs Today

Dirty politics and the “tariff of abominations” divided American voters—and set the stage for years of economic debate.

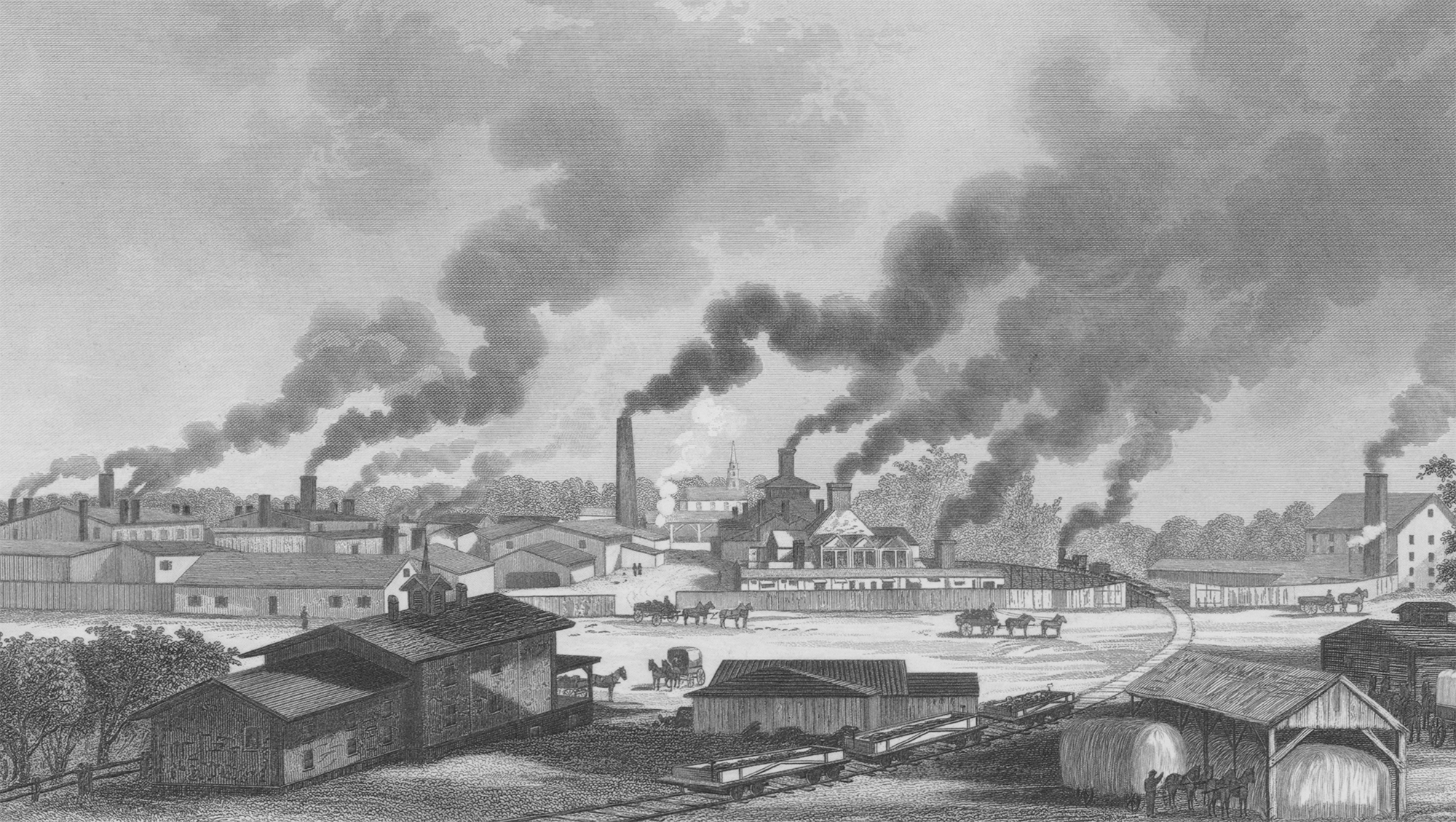

Setting the Scene

Imagine you are there: it is 1828, early in an election year, and you are seated in the halls of the U.S. Congress.

Around you, congressmen are voting on a tariff bill. Tariffs are taxes on imported foreign goods. In the late 1820s, tariffs are a primary source of funding for the U.S. government—around 85 percent of federal revenue typically comes from tariffs. They can also protect American manufacturers by limiting outside competition. But tariffs can make things more expensive for regular Americans. Tariffs have been a contentious issue in these halls for over a decade.

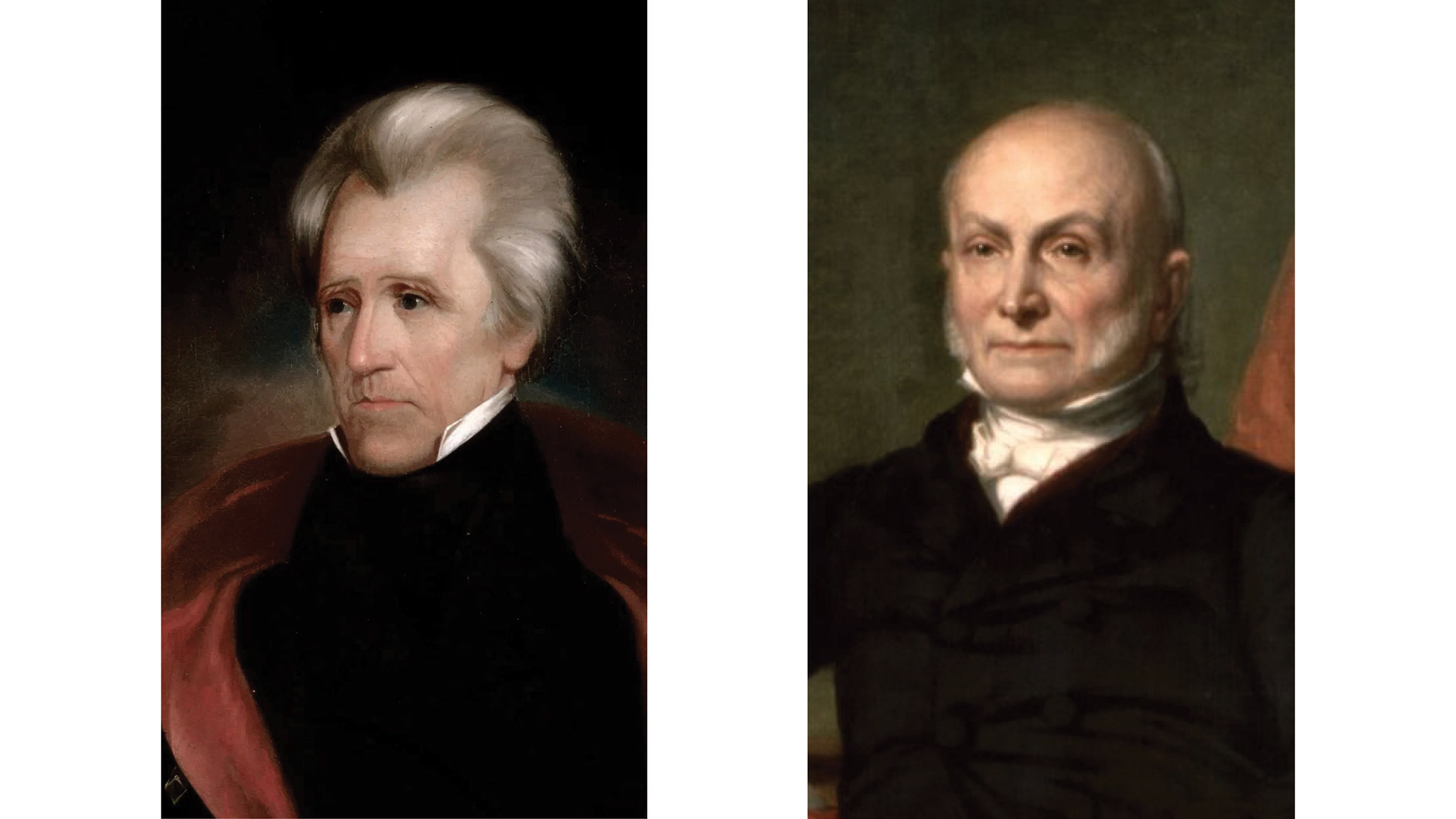

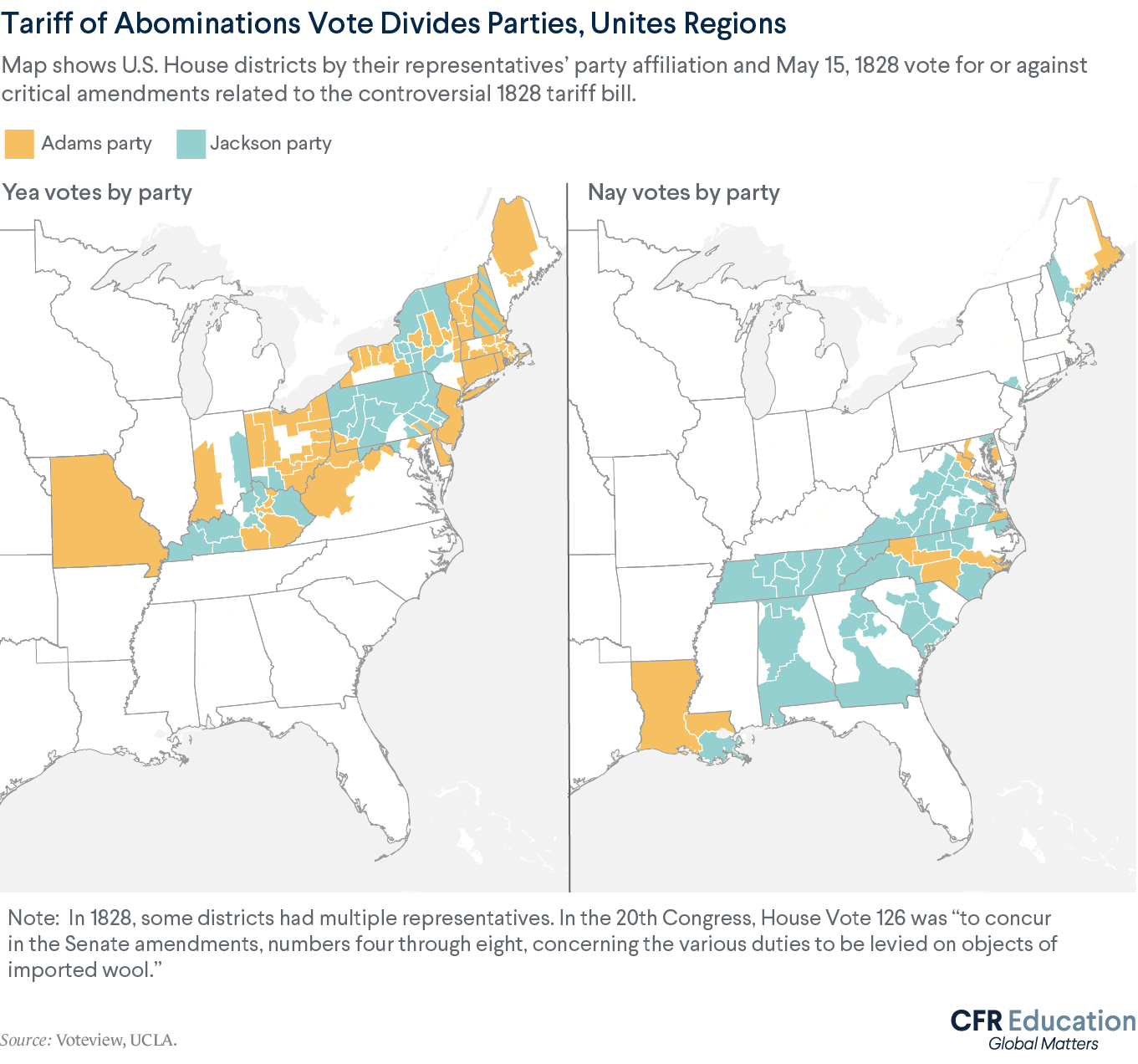

As you look around, you notice a growing division between two political camps. On one side are the Adams men—supporters of President John Quincy Adams. The Adams men are generally protectionists, meaning they favor tariffs. Many of the states they represent tend to benefit from tariffs.

On the other side are the Jacksonians, supporters of former General Andrew Jackson. The Jacksonians are generally split on tariffs; some like them and some don’t. But they all dislike Adams. They are united in that opposition.

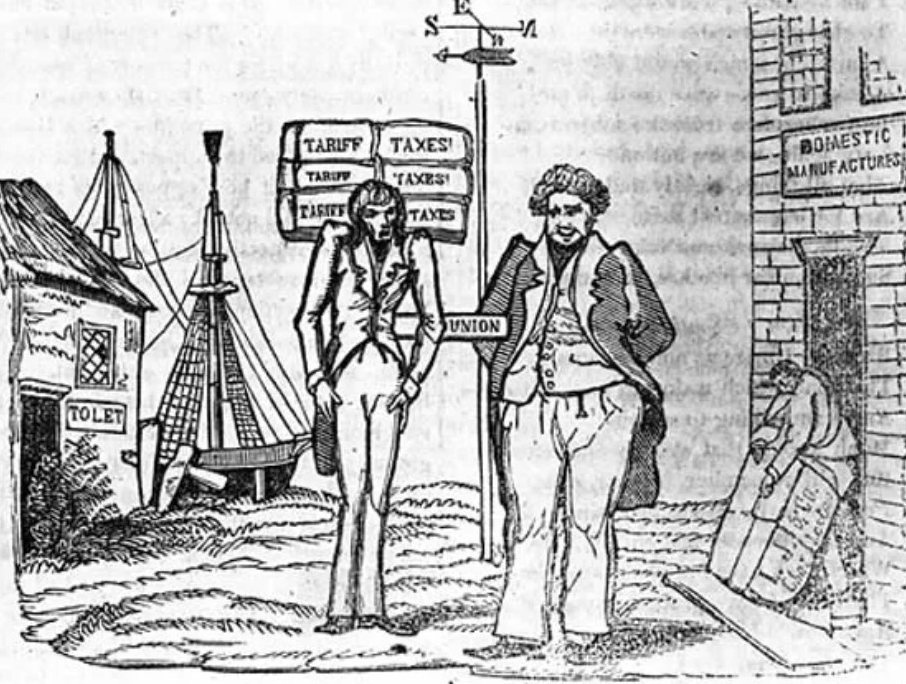

What happens next is a matter of historical dispute. The congressmen are voting on a bill that will significantly raise tariffs. There's consensus that the Jacksonian proposal is supposed to appeal to swing states. Some politicians say the bill was meant to be passed, earning more swing state support for the Jacksonians. However, others disagree, saying that the bill was supposed to draw Adams-supporting congressmen into killing it, making the swing states angry at Adams. Whatever is happening behind the scenes, one thing is clear: the bill is political. Its intent is to help elect Jackson.

When the bill passes, it’s no surprise that those who want lower tariffs are upset. But congressmen who generally support higher tariffs are also angry. They’re mad at which tariffs were raised, as well as the divisive politics involved in its drafting.

Many Americans believe this bill, the “tariff of abominations,” was created to influence the election. But the bill has created a problem for the next president, whomever he will be: he will inherit a country growing divided.

That is the fever in the air as American voters head to the polls.

The 1828 Election: Jackson vs. Adams

The presidential election in late 1828 pitted incumbent Adams against Jackson. It was a heated rematch. Four years ago, Adams had come out victorious. Jacksonians believed the election had been stolen from them.

Jackson was a tall man with a short temper. The former general was prone to violence and confrontation, and he carried evidence of those instincts in the form of two bullets, lodged in his body after two separate duels. Jackson’s support was strongest in the South, where voters were generally against tariffs.

Adams was a veteran statesman and an expert in foreign affairs. He was also stubborn, asocial, and idiosyncratic. The son of former President John Adams, he came from a long line of stolid Yankees. His political base was in New England, where many voters supported tariffs.

This election year would usher in a new era of American politics. By 1828, there were more voters across the country. Some Americans no longer needed to own property to cast their ballots. Those new voters were being reached in new ways too, as newspapers expanded and as politicians began appealing to emotions, not just addressing the issues.

Jackson’s supporters saw 1828 as a year of vindication. They believed Jackson would unseat the allegedly corrupt Adams. Adams supporters disliked the Jacksonians and their legislative maneuvering. Both sides attacked each other. Mudslinging was a common tactic. Jackson’s supporters accused Adams of hustling for a Russian czar. Adams’s supporters called Jackson’s mother a “common prostitute.”

The Ballot Issue Then

For many American voters in 1828, the tariff of abominations was just that: an abomination. For others, tariffs were a boon. Tariffs deepened a national divide that had already been growing. Regional tempers were beginning to flare.

Why were so many Americans ticked off about tariffs?

It depended on where they lived.

Many Adams supporters in New England were outraged at the original tariff bill. Because tariffs are taxes on imports, raising them increases the price of foreign goods (and can lead to higher prices on domestic versions of those goods too). The bill’s original proposals did not help New England’s major industries of shipbuilding and woolen-goods manufacturing. That’s because the bill taxed imports on the materials needed for those industries, like hemp and wool—making them more expensive for New England manufacturers. During the debate, the bill was amended to raise some tariff protections for New England manufacturers, in order to get their representatives’ begrudging support.

Representatives in the South were also upset. The South was generally against tariffs. Southern states heavily relied on slavery for their more agriculture-based economies, and they tended to get more of their manufactured goods from Northern states or from abroad. Taxes on imports made those goods more expensive.

Representatives in the Middle and Western states favored the proposed tariffs most—states like New Jersey, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. Without tariffs, or with lower tariffs, foreign goods cost less—because taxes on them are lower. But cheaper wasn’t better for manufacturers in states like Pennsylvania; lower foreign prices meant competition. A customer could ask: Why buy expensive American products when I can buy cheap foreign imports? Raising tariffs protected American businesses by incentivizing Americans to buy American products. Middle and Western States wanted protection for their own products—goods like wool, hemp, wheat, and corn. Tariffs made those products more competitive.

When the tariff of abominations passed in congress, Southerners were outraged. The bill seemed to favor the Middle and Western States of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, as well as New England. Some in the South called the bill the “Yankee tariff.” But even those in favor of tariffs bemoaned the bill. Many of the tariffs in the law raised the cost of materials that manufacturers needed, increasing their costs instead of supporting their businesses. In the end, the bill was seen as a major political failure. It cast a shadow on the idea of congressional tariff-making.

Jackson went on to win the election that year. However, his personal popularity (and Adams’s unpopularity) perhaps had more to do with the victory than the tariff of abominations. Still, the tariff would be a headache for Jackson. It would further polarize the country, even leading to talk of secession in the South.

The Ballot Issue Now

Many echoes from 1828 reverberate in the 2024 election—not least of which is the polarization and vitriol between supporters of opposing political leaders (though maybe “common prostitute” seems like a sophisticated insult these days). But when it comes to economic policy, tariffs remain a big issue.

In 1828, tariffs were not a foreign policy tool. They were a domestic policy tool, originally intended as tax revenue for the government. Slowly, they also became a strategy for protecting domestic industry and growing the American economy. (Historians and economists disagree on whether tariffs are responsible for the United States’ later economic growth.)

Today, tariffs are also used in other ways, including punishing other countries for unfair trading practices and for protecting national security. Those goals make tariffs more of a foreign policy tool—one that’s becoming more popular.

Tariffs are now a large part of the trade war between the United States and China. President Donald Trump used an aggressive tariff strategy against China when he was in office. He targeted several Chinese goods like steel, aluminum, and solar panels. Trump and others accused China of unfair trade practices, which they claimed threatened U.S. competitiveness, jobs, and security. Those tariffs were meant to punish China, protect American technology, and keep American jobs.

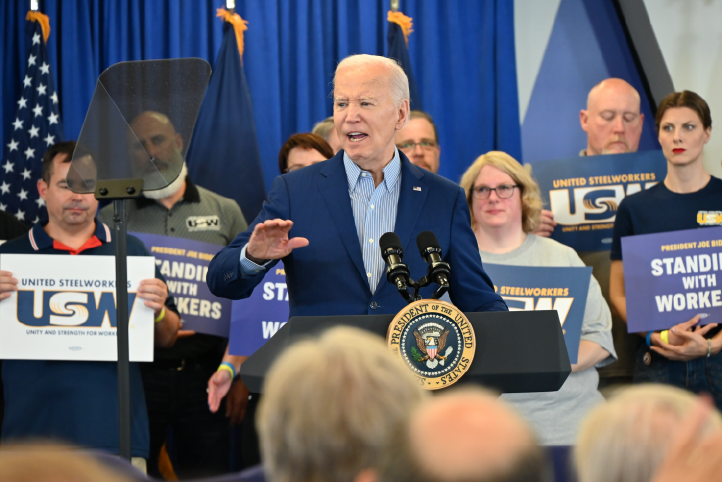

As in 1828, tariffs aren't a completely partisan issue today. Since his election in 2020, President Joe Biden has not only kept many of Trump’s tariffs but also increased them. The goal is the same: put pressure on the Chinese economy and protect American interests.

When it comes to tariffs, American voters may not have much of a choice this November: the Democratic nominee, Vice President Kamala Harris, could follow the Biden administration's strategy, while Trump, the Republican nominee, is poised to escalate it. Just like in 1828, tariff fever could inspire agitation. Some experts estimate that over time, today’s tariffs will hurt the United States’ gross domestic product (GDP), wages, and employment.

Feeling the heat from tariffs could become a problem for American voters—regardless of the candidate for whom they vote.