The 1808 Madison vs. Pinckney Election and Isolationism Today

President Jefferson’s contentious Embargo Act divided Americans at the polls—and raised ongoing questions about America’s role in the world.

Setting the Scene

Imagine you are there: It is 1807, and Britain and France are at war. The French Emperor Napoleon continues his advance east through Europe, thrashing the Russian army. At sea, the British Navy dominates. In their fight against the surging French, the British block trade from the United States, forcing ships through British ports. Napoleon responds by calling for the seizure of American ships entering these ports. The United States is now cut off from its trading partners, unable to safely carry goods to or from France and England.

At this moment in history, the U.S. military is weak. The nation, neutral in the war raging across the Atlantic, seems easily bullied by both European powers. The British have even been boarding U.S. ships and forcing American sailors to work for the British Navy. This forced conscription, called impressment, and the blockades are a challenge to American independence, as well as to American neutrality. European countries watch to see if the United States will pick a side.

The United States does come close to war. Off the coast of Virginia, British warships patrol the waters, blocking French ships from leaving the Chesapeake Bay. Aboard one British ship, a London-born sailor named Jenkin Ratford deserts with four American-born men. They join the crew of a U.S. Navy ship, the USS Chesapeake. In the eyes of the British, America is now harboring traitors.

In June of 1807, as the Chesapeake starts to make its way toward the Mediterranean, a British warship intercepts the frigate just miles off the Virginia coast. The British demand to search the ship for the deserters. The Americans refuse. The British open fire on the Chesapeake, killing three people and wounding another eighteen. The Chesapeake surrenders. British sailors then board the Chesapeake and seize the deserters. The American sailors are given a sentence of 500 lashes each for their desertion, though this punishment is later commuted. For mutiny and desertion, among other crimes, Ratford is hanged.

The attack and seizure of American-born sailors on an American ship—just off the U.S. coast! —infuriates the public. Some cry for war. “Never since the Battle of Lexington have I seen this country in such a state of exasperation as at present,” President Thomas Jefferson writes in a letter, comparing the attack to the first major battle of the Revolutionary War.

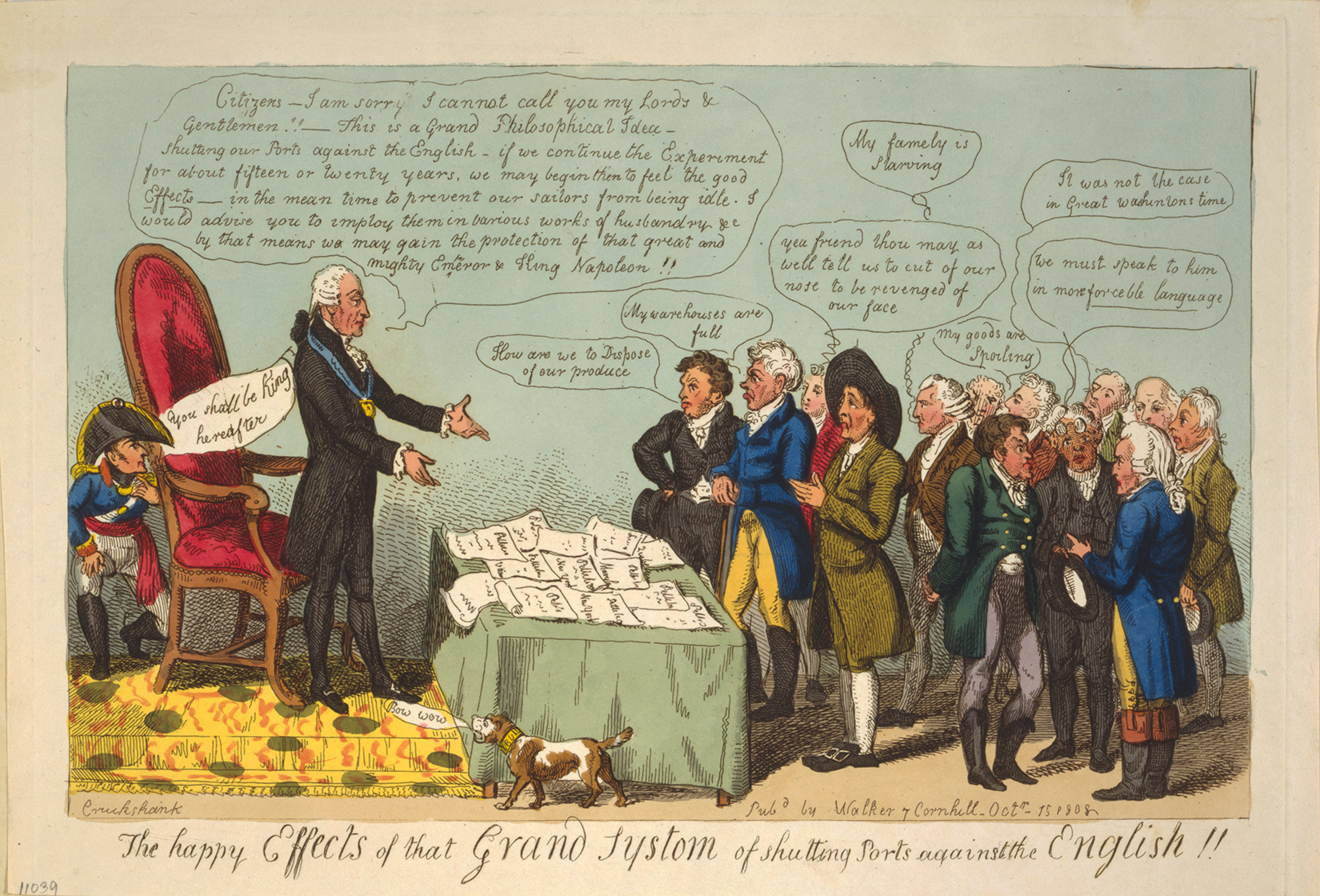

But despite the calls for war, Jefferson is hesitant to battle the British. Instead, he decides on an embargo, or an action taken to stop the flow of imports and exports. The Embargo Act of 1807 prohibits trade with all of Europe. The hope is that as Britain and France are cut off from U.S. exports of commodities like cotton, fish, timber, and tobacco, the Europeans will feel compelled to start respecting American independence in order to regain access to U.S. trade.

However, the embargo seems to have little influence on Britain and France over the course of its first year. Instead, the embargo clearly hurts the American economy, especially in New England, where many depend on maritime trade to feed their families.

In 1807 Americans had cried for war. Now in 1808, they smuggle goods from British Canada and call for an end to the embargo. Few are happy with the federal government, which has begun using its own navy on American ships to enforce the embargo. Some label Jefferson a tyrant.

In this fraught moment, American voters head to the polls.

The 1808 Election: Madison vs. Pinckney

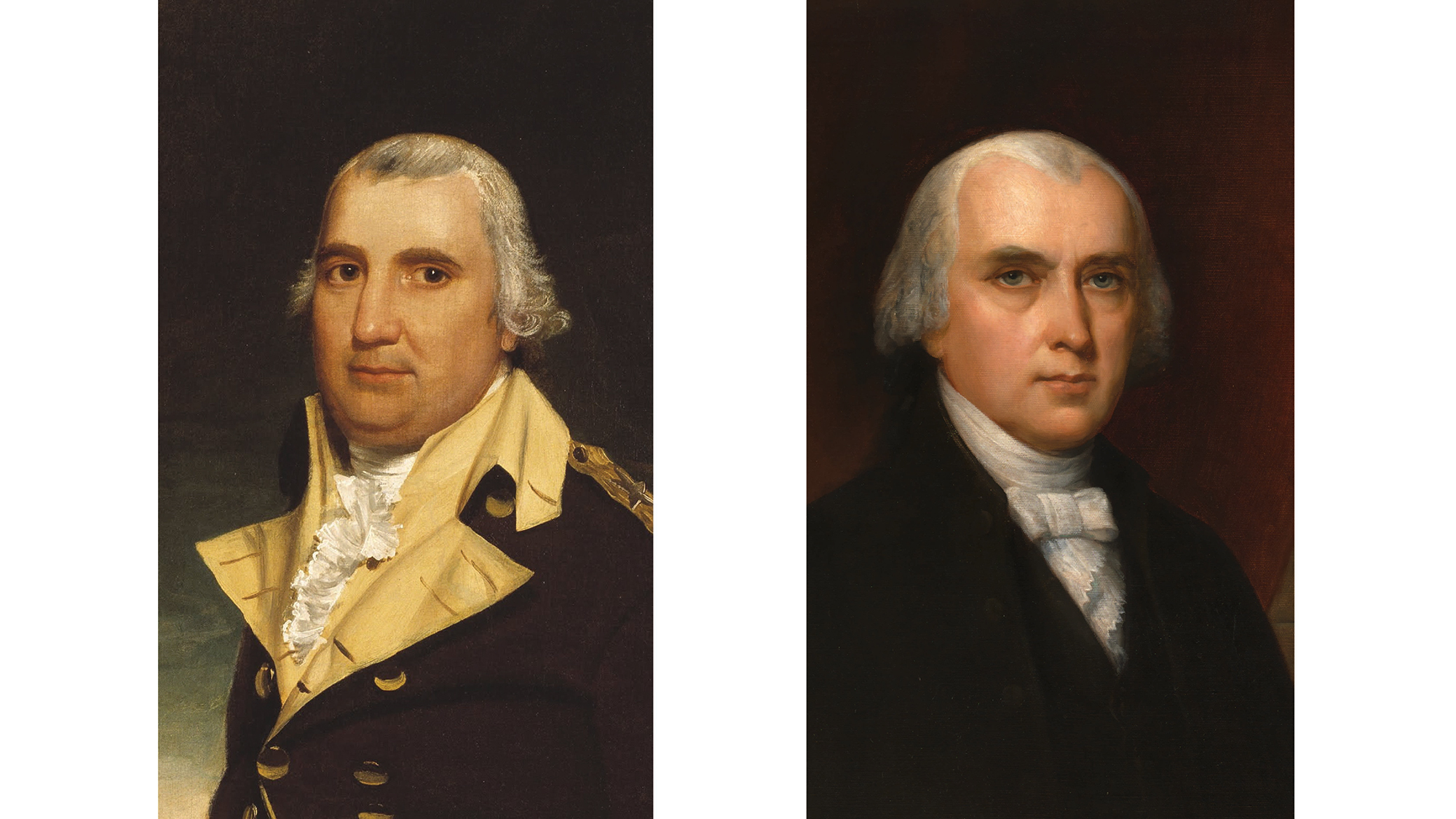

Following George Washington’s precedent, and citing his “advancing years,” Thomas Jefferson (then age sixty-five) decided not to seek a third term in 1808. Instead, he supported his friend and fellow Democratic-Republican James Madison.

At this time, U.S. politics featured two main parties, the Democratic-Republicans and the Federalists.

Democratic-Republicans, led by Jefferson, generally preferred the rights of individuals and states over the powers of the federal government. They were most popular in the southern states. The Democratic-Republican ticket for 1808 included Madison and George Clinton, the vice presidential nominee.

The Federalists, opponents of Jefferson, supported a stronger federal government. Federalism was most popular in New England. In 1808, the Federalist Party nominated Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. Pinckney had run against Jefferson in the previous election in 1804—and lost. For the 1808 election, he was renominated alongside his previous running mate Rufus King, the only time in American history when a major party renominated its previous losing duo.

The Ballot Issue Then

In November of 1808, one of the most contentious issues was still the Embargo Act. By now, the act had been in place for months, and it was hurting the United States more than it was hurting either Britain or France. Americans who had produced the now-banned exports were seeing their incomes drop, as were the people who made a living shipping those items across the ocean.

Federalist popularity had grown, particularly in the Northeast, since the Embargo Act. Americans in the region blamed Jefferson for hurting many of their trade-dependent livelihoods. In New York City, the Federalist vice presidential nominee Rufus King wrote about “the ruin and distress the stoppage of all trade has produced in this city. Bankruptcies follow each other daily.” Many New Englanders also saw Jefferson’s military enforcement of the embargo as tyrannical. In Massachusetts, Jefferson was called a “despot,” worse than the king of England.

Still, some favored the embargo. In the mid-Atlantic region, particularly in Philadelphia, enterprising individuals built small manufacturing operations to produce many of the goods that used to be imported from Europe before the embargo. Some even urged Jefferson to keep trade restrictions, regardless of what the Europeans did, in order to protect their infant industries.

Other supporters were more focused on the original international goals of the embargo. William B. Giles, a Virginia senator and Democratic-Republican ally to both Jefferson and Madison, defended his support for the president’s decision in a speech shortly after the election. Giles said Jefferson had three options after the Chesapeake incident: “the embargo, war, or submission.” Giles argued the embargo was preferable to the other two options. He claimed the embargo protected American sailors and property and that it would succeed in convincing Britain and France to better respect American independence.

But the embargo failed to put meaningful pressure on Britain, which instead increased its trade with Latin America. France was also not significantly hurt and continued to seize American cargo. Still, Giles’s argument showed there was support for the embargo as an alternative to war. And despite Jefferson’s unpopularity among New Englanders, the founding father’s influence was still strong. When Americans voted in 1808, they voted once again for Jefferson’s party, electing James Madison as the next U.S. president.

Criticism of the Embargo Act continued after the election, and before Jefferson left office, he repealed the act, easing the embargo. Early on in his first term, Madison would go further, opening up trade to Britain and France, under certain strategic conditions.

The Ballot Issue Now

President Jefferson had hoped the Embargo Act would put pressure on European governments to respect American independence. He called this strategy “peaceful coercion,” since it relied on economic and not military pressure.

Today, embargoes remain a common way for governments to punish other countries—often over political issues, such as human rights violations. The United States currently has embargoes against Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Syria, and others.

These embargoes, however, aren’t contentious issues in the 2024 election. If there’s an echo from 1808 heard today, it isn’t the embargo itself. Instead, the echo concerns the United States’ role in the world outside its borders.

The Embargo Act was considered a way for the United States to avoid war—or, to avoid taking sides in a war already raging in Europe. Since 1808, the United States has become much more involved in world affairs. But many voters these days wonder if this involvement benefits the United States.

A poll conducted last fall [PDF] by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs asked this question: “Do you think it will be best for the future of the country if we take an active part in world affairs or if we stay out of world affairs?” About 57 percent of Americans favored an active approach. (Just five years earlier in 2018, that number was 70 percent.) An increasing number of those who say America should be less active are Republican voters. Just over half of Republicans, according to this poll, believe the United States should stay out of world affairs.

Opponents of U.S. involvement are often called “isolationists.” Even though isolationist attitudes have gone up and down since the Chicago Council began polling in 1974, the current trend is down. Since the very first Republican debate last year, commentators have been asking if the United States is entering a new isolationist era.

The answer could have major consequences. As in 1808, there is a major war today on the European continent—this time between Ukraine and Russia. Unlike 1808, the United States has the capability to meaningfully influence the outcome of the war, by providing money and weapons to the Ukrainian military.

But support for Ukraine has been contentious. While the Democratic presidential nominee, Vice President Kamala Harris, and many other Democrats have advocated strongly for more aid to Ukraine, many Republican lawmakers have been hesitant to increase aid. Diplomats and former aides to Republican nominee Donald Trump have even told reporters that if he were reelected, Trump would likely push for more isolationist policies, including cutting off aid to Ukraine.

What do American voters think? A Gallup poll this April showed that Americans are divided on U.S. support: 36 percent believe the United States is doing too much to help Ukraine, but 36 percent also believe the United States isn’t doing enough.

That means in November, Americans may not just be voting on the next president. As in 1808, they may be voting on how their country interacts with the rest of the world.