Modern History and U.S. Foreign Policy: Europe and Eurasia

From World War I to the War in Ukraine, learn how history and U.S. intervention has shaped the region.

For the past seventy-five-odd years, Europe has largely been at peace. But for much of its history, Europe was at war—with itself.

Epic campaigns fought over religion, territory, and political power—like the Hundred Years’ War, Thirty Years’ War, and Napoleonic Wars—wiped out huge portions of the population. Meanwhile, Borders shifted as empires rose and fell. For example, since 1461, the city of Sarajevo has been part of nine different empires, kingdoms, states, and countries.

Sometimes these conflicts led to diplomatic innovations: the 1648 Peace of Westphalia established the modern concept of sovereignty, the principle that countries have the right to control what happens within their borders, and should respect other countries’ boundaries.

But after each peace treaty, even one as significant as Westphalia, war broke out again.

In the twentieth century, Europe became a primary site of two of the most deadly conflicts in modern history. At the start of the century, World War I devastated the continent. Despite assumptions that it was “the war to end all wars,” the conflict, and its tumultuous aftermath, merely set the stage for an even deadlier World War II just decades later.

The decades following World War II in Europe saw Cold War tensions split the continent along ideological lines. Yet this period was also one of unprecedented diplomatic integration, with the emergence of institutions like the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

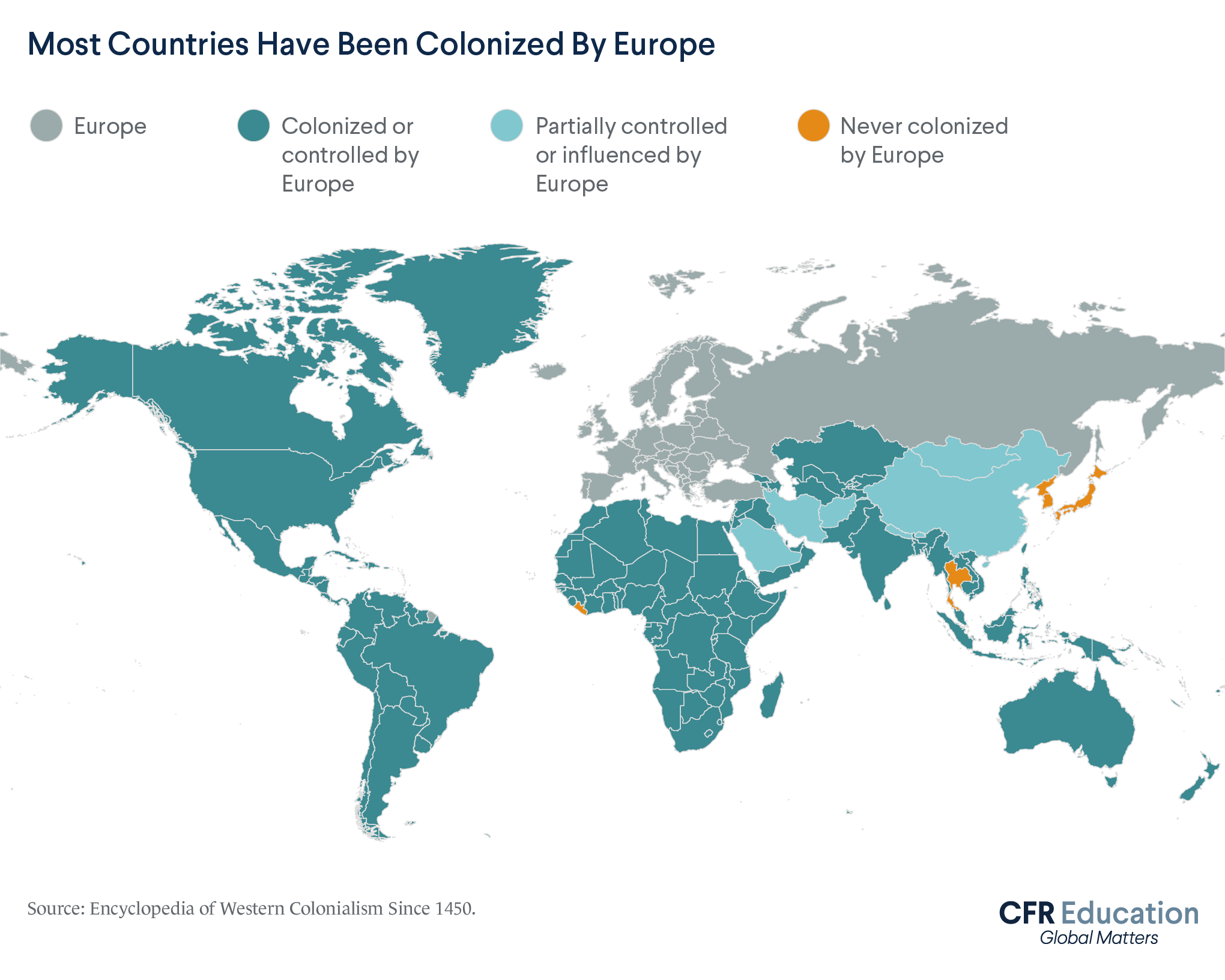

Meanwhile, Europe’s long-held colonies in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia began to challenge colonial rule. Independence movements resulted in the emergence of dozens of new countries around the world. Decolonization and its aftermath also saw numerous violent conflicts take root, and brought questions of European countries’ responsibility for its colonial legacy to the foreground.

The twentieth century also saw a former European colony—the United States—take an increasingly active role in European affairs. The United States emerged from World War II as a superpower with global interests, and it invested heavily in the security and economic prosperity of Europe. No longer an isolationist country, the United States would go on to forge deep and lasting ties with Europe.

Recent decades have brought new challenges to Europe: economic crisis; an influx of refugees from conflicts in the middle east; climate change; and rising isolationist sentiment in the United States have reshaped the way European countries interact with one another, and the world. Most recently, Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and subsequent full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 have once again brought the specter of war to the continent.

How did we get to this point?

Here are some of the most important events in modern European and Eurasian history—and how U.S. foreign policy has shaped the region.

1914 - 1918

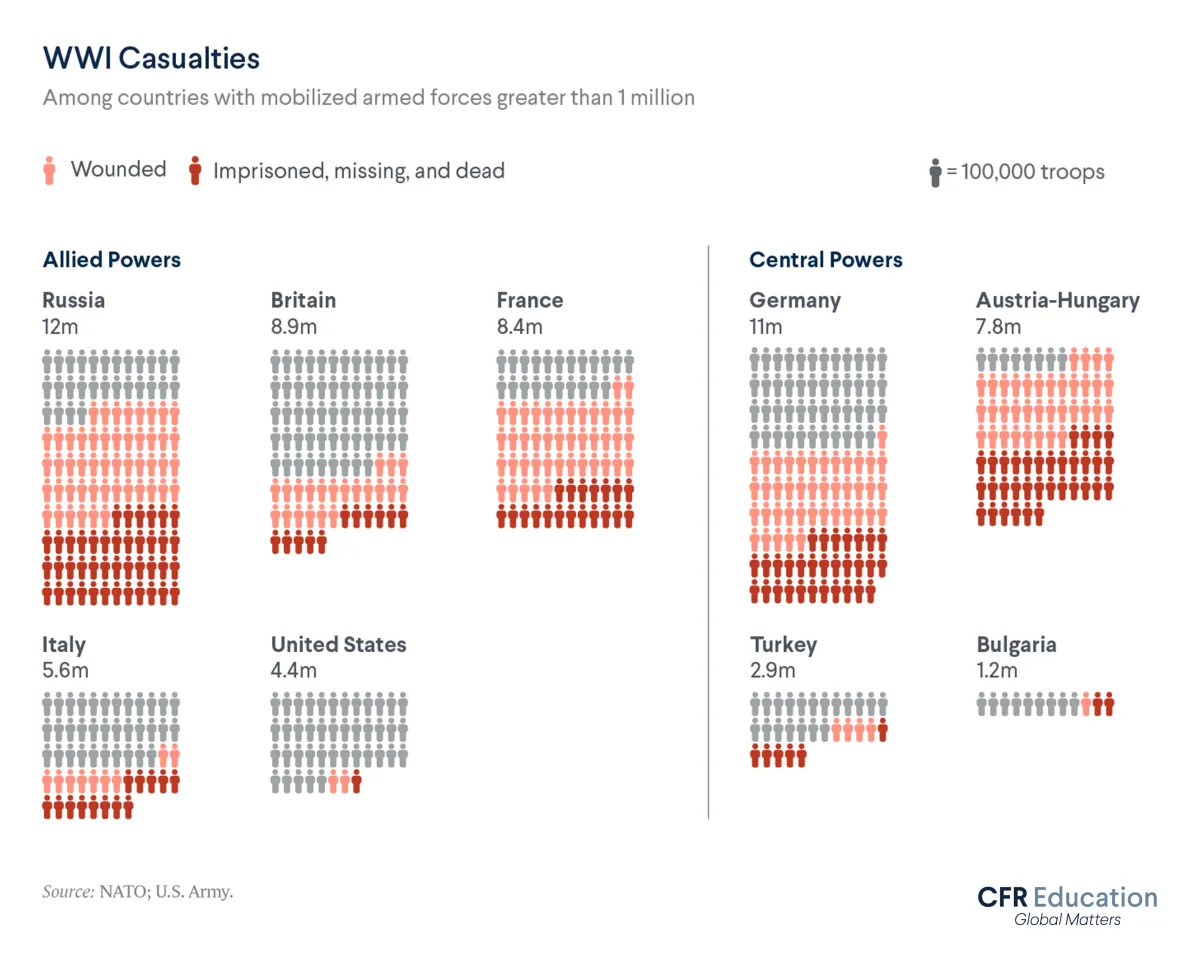

World War I Devastates Europe

By 1914, Europe was divided into two rival alliances: Austria-Hungary, Germany, and Italy (the Triple Alliance) and France, Great Britain, and Russia (the Triple Entente). For a time, this rivalry maintained an uneasy peace. But then in June 1914, a Serbian terrorist assassinated the heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary. The event reverberated throughout Europe as countries rushed to defend their allies. War broke out. The toll was catastrophic: at least 8 million soldiers and unknown millions of civilians (estimates range from 5 million to 10 million) died. Four European empires—Ottoman, Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian—collapsed, creating a number of fledgling countries with new, sometimes arbitrary borders and unstable economies. Germany—deemed the primary aggressor by the victorious allies—took a large hit. The peace agreement, the Treaty of Versailles, imposed war debts on Germany and forced it to accept all responsibility for starting the conflict. Meanwhile, the United States, which suffered modest losses compared to Europe, retreated back across the Atlantic instead of leading the charge on international cooperation—all of which created instability rather than resolution. Soon, Europe was at war again.

1917

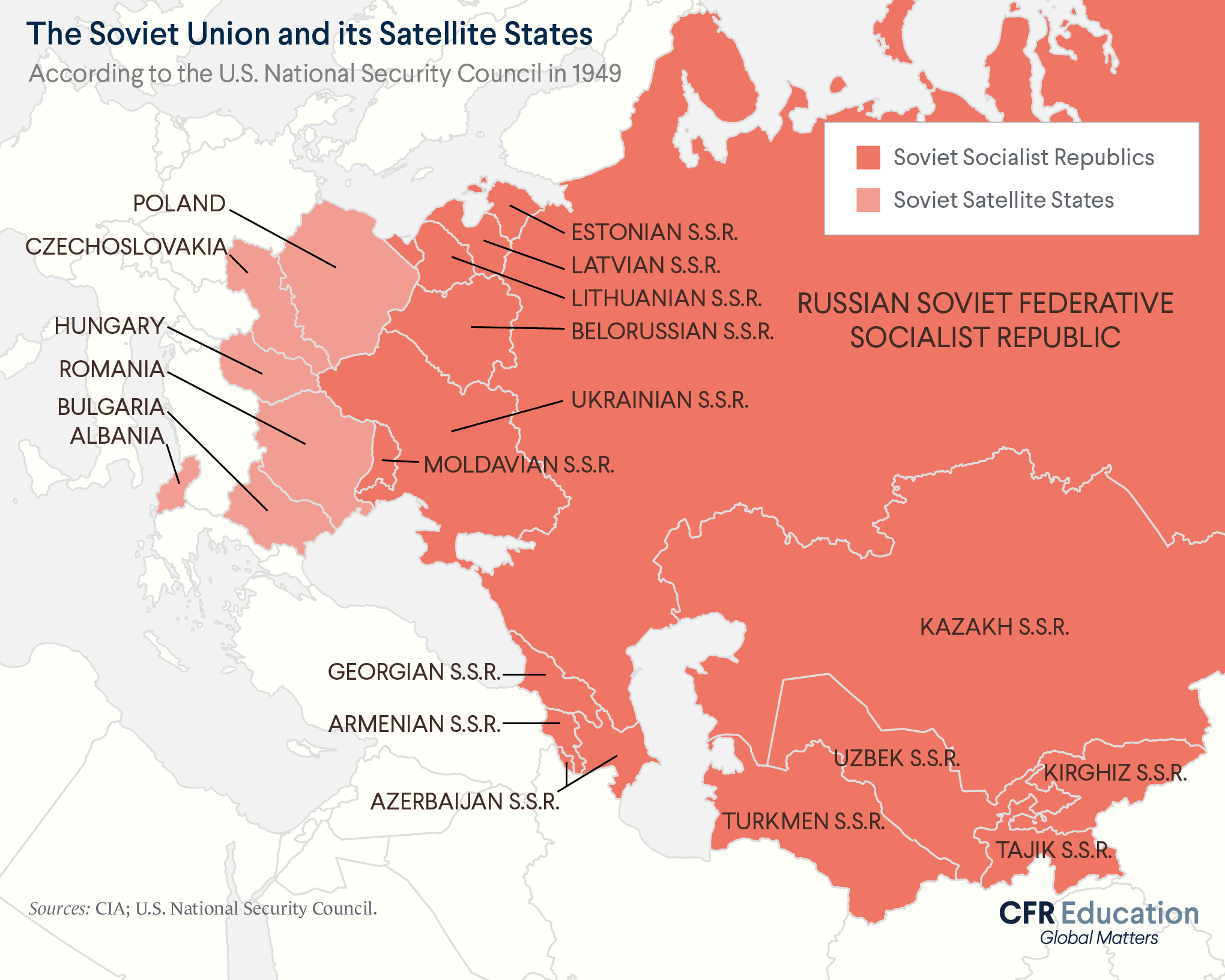

A New Russia Is Born

While World War I was raging, a separate conflict erupted in Russia. In 1917, millions of Russians overthrew their centuries-old monarchy and soon established the world’s first socialist country. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), or the Soviet Union, brought together Russia and fourteen other ethnic republics previously ruled by the Russian Empire. From Moscow, the Soviet Union exerted its influence over a half-dozen nominally independent countries in Eastern Europe that came to be known as Soviet satellite states. In the Soviet Union, the government controlled all major resources like land and steel; although education and industrialization spread rapidly, political repression was brutal. From the 1920s to 1953, millions of civilians were executed, sent to a system of labor camps known as the Gulag, or starved in forced famine under the rule of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. All the while, the Soviet Union solidified its role as a global superpower.

1925 - 1938

Fascism Grips Europe Between World Wars

In 1936, General Francisco Franco launched a bloody coup against Spain’s young democratic government and, following three years of civil war, ruled as dictator. Franco joined a string of strongmen leaders in post–World War I Europe, all of whom amassed power by violently suppressing opponents and dismantling democratic institutions like free elections and an independent press—characteristics of an ideology that came to be known as fascism. The continent’s first fascist leader, Benito Mussolini, made himself dictator of Italy in 1925; Adolf Hitler followed in 1933. Their messages emphasized national strength, and, in Hitler’s case, racial hierarchy. The messages resonated in some countries where the unsettling new forces of globalization, capitalism, immigration, and agricultural technologies collided with the physical and economic devastation of the First World War. But many Europeans did resist fascism, as demonstrated by the bitter Spanish Civil War. Thousands of foreign volunteers flocked to Spain to fight on the side of the republican government and defend democracy. It was, in a sense, the first battle of World War II.

1939

World War II Strips Europe of Global Supremacy

In 1939, Hitler invaded Poland—Nazi Germany’s first step in a plan to conquer Europe. Countries that had spent the past decade avoiding the growing reality of another major war were now involved in a global conflict of an even greater scale than the previous world war. World War II would become the deadliest conflict in human history; an estimated sixty million people—3 percent of the world’s population—died. Both the Axis powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan) and the Allies (France, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and later, the United States) targeted civilian populations, leveling cities including Dresden, London, and Tokyo. Germany surrendered in May 1945, bringing an end to the war in Europe. Europe entered the twentieth century as the premier global power. It emerged from World War II subordinate to the new superpowers: the United States and the Soviet Union.

1941

U.S. Intervention in World War II Paves Way for American Engagement

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, the United States, wary of getting embroiled in another overseas conflict and still grappling with the Great Depression, opted to remain mostly on the sidelines. By the end of 1941, Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany was well on the way to victory. Germany and Italy—two of the Axis powers, along with Japan—controlled most of continental Europe. France had surrendered. The Soviet Union, which had previously signed a nonaggression pact with Germany, was caught off guard when Germany invaded. The United Kingdom found itself almost alone, and vastly outnumbered. But then on December 7, 1941, Japan attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, pushing the country into World War II. When the first U.S. troops landed in Europe the very next year, the tide began to shift: Germany found itself caught in between a Soviet counteroffensive on its eastern front, and a decisive U.S. offensive in the west. When Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, the United States stood victorious and in a powerful position to direct Europe’s post-war future. One considerable obstacle emerged, however: the Soviet Union.

1945

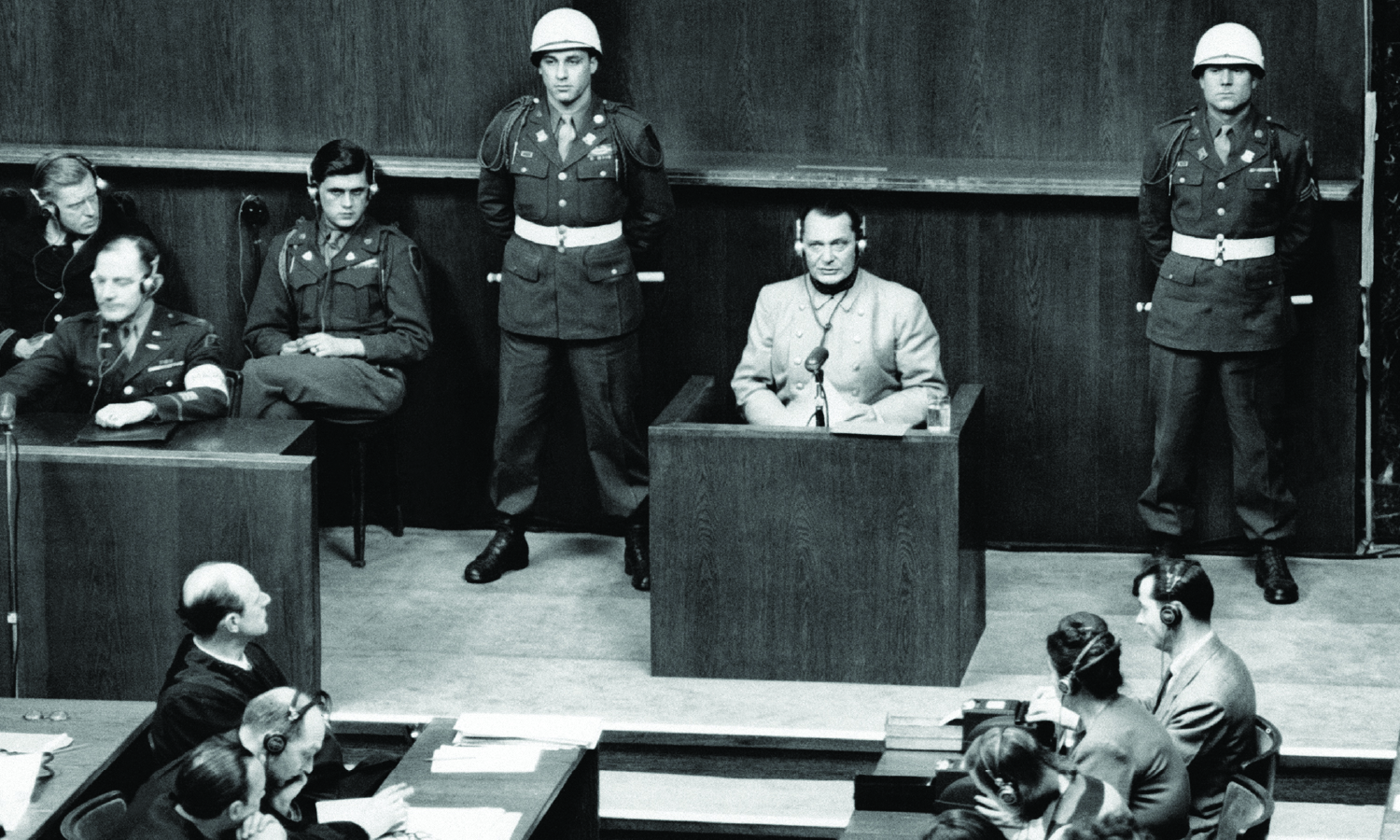

The Holocaust, Nuremberg Trials, and the Birth of International Human Rights Norms

After World War I, Hitler’s Nazi party began taking increasingly violent measures against Germany’s Jews: revoking their citizenship, denying them basic civil rights, burning synagogues, and attacking and killing the Jewish people. Hitler believed the German people (the so-called Aryan race) were entitled to greater living space in Eastern Europe, at the expense of the non-Aryan populations who lived there. From 1941 to 1945, Germans and their allies systematically rounded up European Jews and others deemed outside the Aryan race (including the Roma, Slavs, homosexuals, and the mentally disabled). They were either shot en masse or sent to concentration camps across Germany and Poland—where the majority were killed in gas chambers. In total, roughly six million European Jews were killed in the Holocaust; historians estimate that up to half a million Roma and Sinti people were also killed, along with a quarter million disabled people and tens of thousands of others. After the war, some Nazi officials who helped carry out the Holocaust were tried and charged with crimes against humanity. These trials, held in Nuremberg, helped establish precedents for punishing international criminal acts that continue to shape international norms to this day. Terms like genocide emerged as part of a canon of human rights law designed to ensure that this dark chapter in history would not be repeated.

1945 - 1947

A New Kind of War Emerges

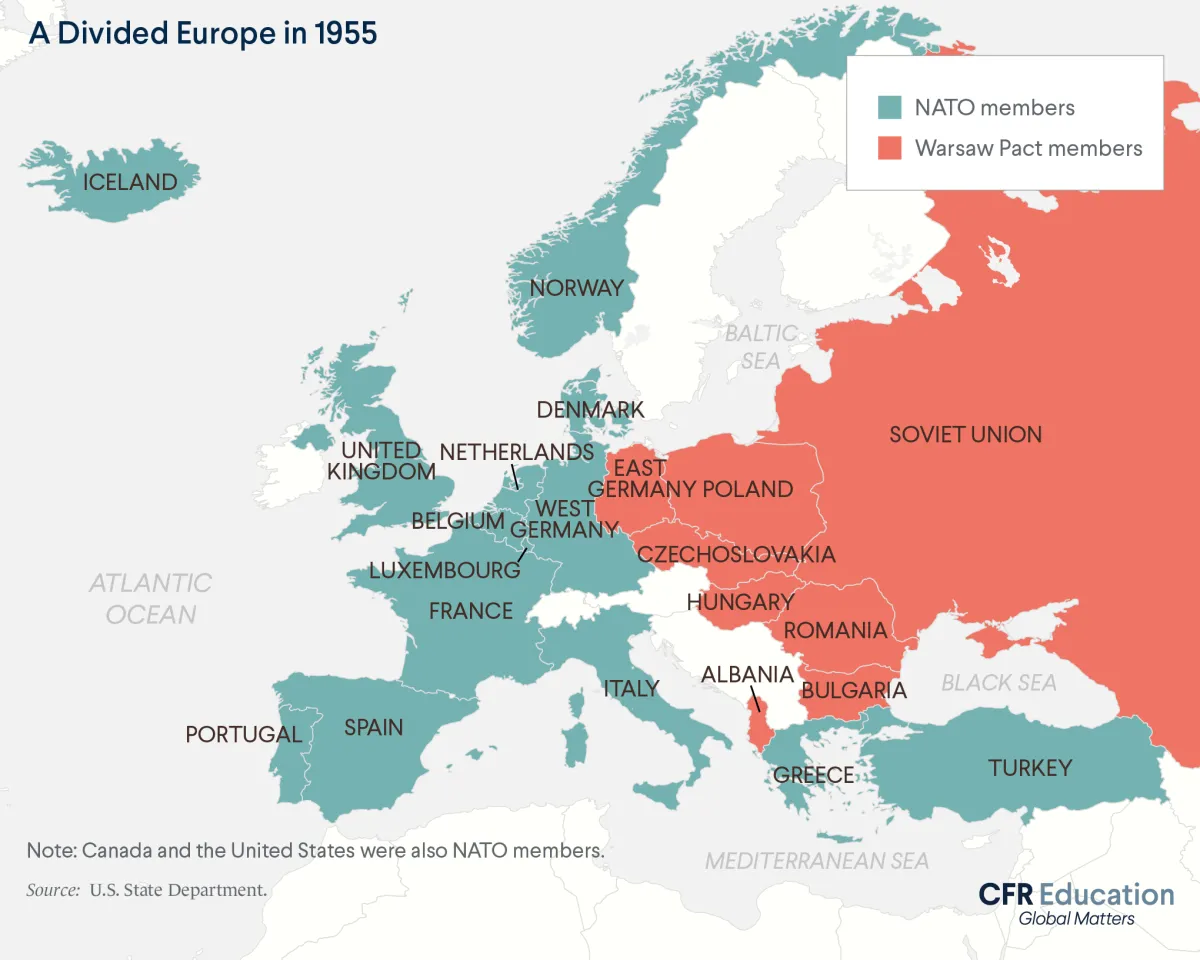

After World War II, the Soviet Union emerged as a major power, ambitious to expand its influence. Led by Joseph Stalin, the Soviet Union began supporting communist governments across Eastern Europe. Germany was divided into two countries: East Germany—a communist Soviet satellite—and West Germany—a U.S.-backed democracy. As Europe divided along ideological lines, the threat of Soviet influence became clear—a direct challenge to the United States and its promotion of democratic, capitalist governments. The United States faced a dilemma: should it directly confront the powerful Soviet Union and risk another major conflict, or should it look the other way, potentially allowing communism to spread? Instead, Washington opted for a third approach: containment. This strategy sought to maintain a balance of power between the United States and the Soviet Union but pledged to confront the Soviets when that balance was threatened, especially in areas geopolitically important to the United States. Guided by the logic of containment, Washington entered a decades-long standoff with Moscow that came to be known as the Cold War. Although a direct conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union never occurred, the Cold War erupted into several “hot wars” between proxy forces around the world, creating arenas for the two superpowers to come into conflict in countries like Korea, Cuba, Vietnam, and Afghanistan. Europe itself was fairly stable; while conflicts did flare up, like when the Soviet Union invaded Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968, the high-stakes threat of nuclear war kept things mostly cold.

1948

U.S. Marshall Plan Rebuilds Europe, Draws Cold War Boundaries

World War II devastated Europe, displacing fifty million people as fighting destroyed entire cities. The United States, meanwhile, emerged as a global power. This time, instead of retreating across the Atlantic as it did following World War I, it worked to prop Europe back up. In 1947, U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall announced a multibillion-dollar plan to provide aid to any European country trying to rebuild its economy. But the Marshall Plan was not merely charity; it was a cornerstone of U.S. Cold War strategy. The United States believed that Europe’s physical, economic, and political collapse made it vulnerable to encroaching Soviet influence. In providing aid, the United States sought to shore up its democratic allies. Sure enough, each of the sixteen Western European countries that accepted funds from the $13-billion-Marshall Plan (more than $130 billion in today’s dollars) experienced rapid economic recovery and deepened relations with the United States. The Soviet Union and Eastern European countries, on the other hand, rejected the aid, fearing it would give the United States influence over their economies.

1949

An Unprecedented Alliance: The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

In addition to rebuilding Western Europe’s economies, the United States helped ensure the region’s security following World War II. In particular, the United States feared the Soviet Union’s growing military presence in Europe following a 1948 revolution in Czechoslovakia, which installed a communist government on Germany’s border. In response, the United States agreed to provide military assistance to rebuild Western Europe’s armies, and in 1949 the United States, Canada, and ten European countries formed a military alliance known as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The cornerstone of this alliance was mutual security, the pledge that an attack on one country would be treated as an attack on all. This groundbreaking peacetime alliance made the United States—with its outsized military strength—effectively the defender of Western Europe. During the Cold War, the United States stationed more than four hundred thousand troops throughout Europe along with missiles positioned to strike Moscow. In 1955, after NATO admitted West Germany to the alliance, Moscow created its own regional alliance, the Warsaw Pact, which included East Germany and the other Soviet satellite states in Eastern Europe. In practice, Europe was now divided between an American sphere in the west and a Soviet one in the east.

1945 - 1960

European Colonies Gain Independence

Beginning in the fifteenth century, competition between leaders in Europe and the search for resources and new markets drove European powers to colonize land overseas. From 1492, when a Spanish expedition landed in the Americas, to the start of World War I, Europe—accounting for just 8 percent of global land mass—controlled more than 80 percent of the world. Europeans profited immensely from colonization, which came at the direct expense of colonized communities and was responsible for violence, enslavement, and forced religious conversion, resulting in the destruction of entire civilizations. Europeans also reshaped the areas they colonized, exporting ideas about government and religion, creating new trading routes, and introducing new technology. But the often violent and exploitative practice of European colonialism began to decline over the course of the twentieth century. There were several reasons for this timing: World War II all but bankrupted Europe, leaving many countries unable to afford the cost of operating overseas colonies; growing nationalist movements within colonial territories drove increasing resistance to outside rule; and emerging institutions like the United Nations began to champion principles of equality and self-determination. Between 1945 and 1960, dozens of colonies across Asia and Africa became independent countries—including India, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, and Vietnam. European countries would still hold on to colonial territory throughout the 20th century. But Europe’s influence over the world was now clearly shrinking, overshadowed by the Cold War powers of the United States and Soviet Union.

1975

From Brief Detente, Agreements Emerge

Starting in the late 1960s, a decade-long thawing of the Cold War, known as détente, eased tensions between NATO powers and the Soviet Union. The nuclear arms race was taking an economic and geopolitical toll: the Soviets had lost their alliance with powerful Communist China, and the United States was still mired in the Vietnam War. Amid these circumstances, the two sides agreed to a series of agreements aimed at decreasing the spread and development of nuclear weapons technology. Détente extended beyond nuclear agreements, too. In 1975, the two powers signed the Helsinki Accords, along with Canada and every European country except Albania. Since the 1950s, the Soviets had been seeking recognition of post–World War II borders. This agreement delivered recognition in exchange for guarantees from the Soviets— on human rights protections and the free flow of information. The Helsinki Accords led to greater economic and political cooperation between the NATO and Warsaw Pact powers. But by the end of the 1970s, détente was breaking down. The Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, and arms control talks stalled.

1986

Soviet Leadership Changes Tactics

The 1980s was a decade of change in the Soviet Union. Mikhail Gorbachev, who came to power in 1985, represented a new era of Soviet leadership. Twenty years younger than his three predecessors, Gorbachev believed the Soviet Union, which was suffering from economic stagnation, needed to reform and modernize. Gorbachev took steps away from the authoritarianism of his predecessors, introducing elections and free speech reforms. He also eased off Cold War competition by halting Soviet missile deployments amid increased U.S. pressure. Meanwhile, since his election in 1980, U.S. President Ronald Reagan had pledged to take on the Soviets more directly, ramping up military spending and arming anti-communist movements in Africa, Asia, and Latin America in the 1980s. Gorbachev tried to reform the Soviet Union to strengthen—not dismantle—it. But targeted changes eventually led to more sweeping ones, as the authoritarian system proved too inflexible to bend without breaking. Gorbachev’s reforms, coupled with Reagan’s aggressive foreign policy brought the Soviet Union to its weakest point.

1989

Fall of Berlin Wall Signals New Era

When Germany was divided into two countries, so was its capital, Berlin. Despite being located deep within East Germany, West Berlin remained a democratic and capitalist enclave. In 1961, East Germany constructed a nearly 100-mile-long wall through the city to physically divide Berlin. For decades, the Berlin Wall became a defining symbol of a divided Germany—and a divided Europe. But when the Soviets relaxed oversight of their satellite states in the mid-1980s to focus on domestic reforms, East Germans began protesting against communist control. In November 1989, officials abruptly announced that East Germans were now free to cross into West Germany. Crowds gathered at the wall with music, champagne, and sledgehammers. Eleven months later, Germany was reunified. The democratic momentum swept across other Soviet satellite states; Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Bulgaria all saw their communist regimes topple. The democratic momentum in Soviet satellite states, combined with Gorbachev’s political reforms, destabilized communist control within the Soviet Union and contributed to its eventual collapse in 1991, marking a swift end to the Cold War, a conflict that had endured for almost fifty years.

1991

Soviet Collapse Introduces New Questions

The Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, marking the end of the four-decades-long Cold War. Western leaders celebrated, but Moscow’s collapse presented new challenges. Breaking the Soviet Union into fifteen independent countries was hardly a simple process. Borders that had once been little more than lines on a map became contentious; Crimea, for instance, became a point of simmering tension between Russia and Ukraine, both of which laid historical and cultural claims to the peninsula. Of more immediate importance to outside observers was the fate of the Soviet arsenal of approximately thirty-nine thousand nuclear weapons, now spread across several new and potentially unstable countries. Over the following years, the former Soviet Republics of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine agreed to relinquish their nuclear weapons, leaving Russia as the sole nuclear-armed successor of the Soviet Union.

1991-1995

Yugoslavia’s Violent Dissolution

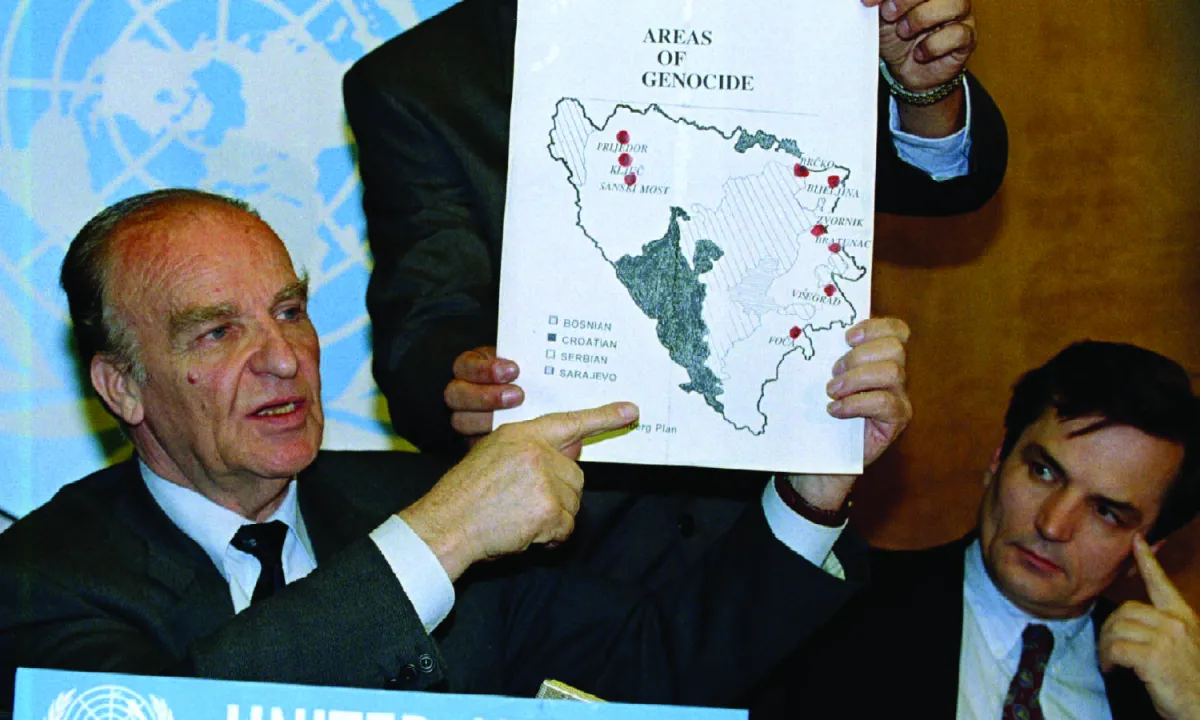

The Soviet Union was not the only country to break apart at the end of the Cold War. When Yugoslavia’s leader, Josip Broz Tito died in 1980, the country found itself in debt and political disarray. The government had little authority to curb growing independence movements in its constituent republics. In 1991, Croatia and Slovenia separately declared independence; each were met with force from the predominantly Serbian Yugoslav military. When Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence the following year, Serbian-backed Bosnian Serbs carried out a brutal campaign of ethnic cleansing against Bosniaks, a Muslim minority, and Croats. The Bosnian Genocide claimed more than one hundred thousand lives and displaced millions more. The larger war ended with the 1995 Dayton Accords, brokered by the United States and its NATO allies alongside Russia.

1991 - 1997

NATO Expands its Mission, and its Membership

At the end of the Cold War in 1991, NATO faced the question of whether it should continue to exist after the collapse of its principal adversary, the Soviet Union. Rather than retire one of history’s most successful military partnerships, NATO officials reimagined it. The alliance would become a military coalition aimed at upholding peace and democratic values in Europe, and willing to confront new challenges beyond the continent. The first test of this mandate came when the alliance intervened in Yugoslavia’s bloody civil war amid reports of ethnic cleansing. At the same time, the alliance began to grow. Former Soviet satellite states, and even former Soviet Republics, sought to enter the alliance, fearing that Moscow could one day seek to reassert its influence. In 1997, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland formally joined the alliance in the first of several rounds of expansion. For the next thirty years, this reimagined NATO would not only operate strictly defensively in Western Europe, but also deploy to missions well beyond the continent, in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and elsewhere.

1993

Europe Forges a New Union

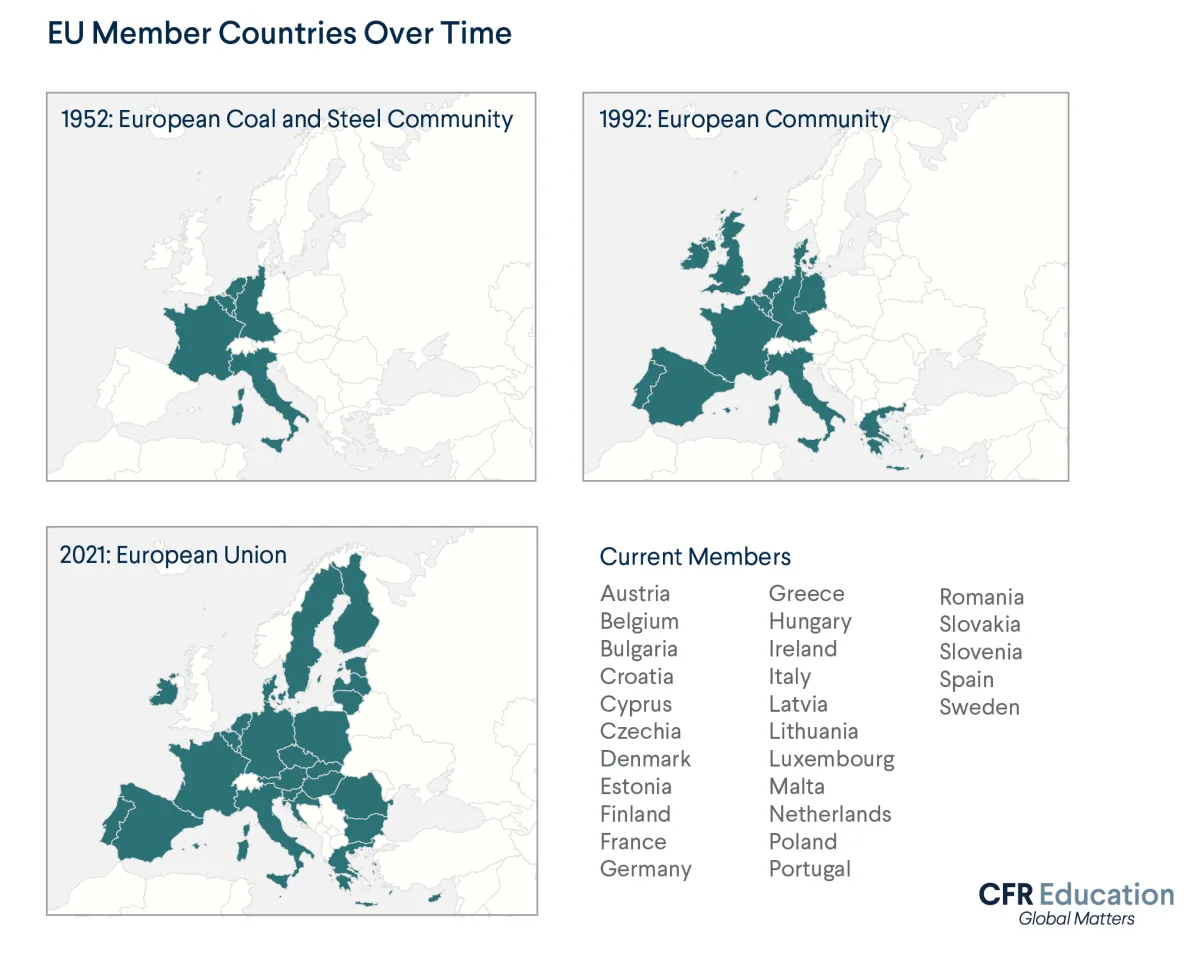

In the aftermath of World War II and as the Cold War began to settle in, Western Europe sought to prioritize cooperation. To combat the Soviet Union, it needed to embrace West Germany. But a strong Germany still inspired fear, especially in its next door neighbor and historical rival, France. In 1950, France’s foreign minister proposed a simple solution: France and Germany could share resources, specifically the coal and steel industries. Sharing resources would create economic opportunities—and make war more costly. The result was the European Coal and Steel Community, which included six European countries. Throughout the cold war, formal European alliances expanded. In 1967, the Community evolved into a larger organization, the European Community (EC). And in 1992, the EC became a full-fledged economic and political union, known as the European Union (EU). The Maastricht Treaty, which created the EU, laid the groundwork for a common European currency, the euro—the culmination of European economic integration. The EU worked to secure “four freedoms” for its members: free movement of people, goods, services, and money. Meanwhile, pathways were opened for new countries to join the EU, expanding the group’s reach and—so members hoped—forging an ever-closer union among European countries.

2004

As the EU Grows, Iraq War Divides NATO

Ten countries joined the EU in 2004, more than any other single year: the Czech Republic, Estonia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia. But as the EU grew, so did divisions between the continent and its most powerful ally, the United States. In the 1990s, NATO members joined the United States in its military campaign in the former Yugoslavia. And after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, NATO joined the United States in the war in Afghanistan—the only time the collective defense pledge, Article 5, has been invoked. But when the United States invaded Iraq in 2003, the move divided the Atlantic alliance. Some countries such as Poland and the United Kingdom sent troops to help with the occupation of Iraq. Meanwhile, France and Germany led a political coalition that opposed the intervention, with France threatening to veto the United States’ efforts at the United Nations. The European public overwhelmingly opposed the war, signaling a divide between their own interests and those of the United States.

2008

Russia Invades Georgia, Renewing Confrontation with the West

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russian leadership passed to Boris Yeltsin and then to Vladimir Putin, who served two consecutive terms before being re-elected for a third term in 2012—despite claims of election fraud. Putin scorned his predecessor's warmer relations with the West. The United States had sent economic advisors and billions of dollars to help restructure Russia’s economy after the Cold War. The two countries even signed landmark arms control agreements. But in less than twenty years, rivalry returned. Not all experts agree over what changed. Some point to Putin’s stoking of anti-Western sentiments. Others suggest that Russia bristled at NATO’s enlargement and the perceived humiliation of the former Soviet superpower by the West. What is clear is that relations turned sour. In 2008, U.S. President George W. Bush expressed support for Georgia and Ukraine—both former Soviet Republics—to eventually join NATO. Months later, Russia invaded Georgia to support pro-Russian separatist regions. Then in 2014, Russia invaded and annexed the Ukrainian region of Crimea and began supporting pro-Russian separatist forces elsewhere in Ukraine . The United States and Europe responded with sanctions. But these measures did little to deter future escalation, or rekindle cooperation and diplomacy with Russia.

2016

Under Trump, Washington Questions its Alliances in Europe

Since the end of World War II, one basic principle has shaped U.S. foreign policy: strong alliances enhance the United States’ power around the world. In turn, U.S. presidents since the 1940s have all sought to cultivate close relationships with allies in Europe—countries like France, Germany, and the United Kingdom—that share the United States’ outlook on democracy and world order. But beginning in 2016 with the election of Donald Trump as president, the United States has begun to question the value of the U.S.-Europe partnership. Trump publicly attacked America’s closest allies, derided countries for not contributing enough to NATO, and even considered withdrawing the United States from the alliance altogether. Meanwhile, he warmed up to authoritarian politicians in Hungary, Poland, and even Russia. In 2024, Trump once again won the presidency, maintaining his previous anti-NATO rhetoric. While the United States has long believed that a strong, democratic Europe is in its own interest, the country may now be returning to its post–World War I isolationist tendencies by questioning such decades-long alliances.

2020

Brexit: The United Kingdom Leaves the EU

In 2016, a slim majority of British voters (52 percent) opted to leave the EU—the first time a country had voted to do so. But this exit was not smooth. In the years after the Brexit vote, Britain’s attempt to navigate a path out revealed just how interdependent Europe had become. That interdependence, in a way, demonstrated the arguments of both sides: the “Leavers” claimed that the EU exerted too much control over Britons’ lives, while the “Remainers” pointed out that losing EU benefits (like access to the world’s largest trading zone) would harm British people in many ways. It quickly became clear that no one had a plan that could both rid Britain of unpopular entanglements without sacrificing certain EU benefits. The United Kingdom officially left the EU on January 31, 2020. Since then, most analysts agree the departure has harmed the country's economy. Bloomberg has estimated that Brexit is costing the United Kingdom around $124 billion each year. And according to Goldman Sachs, as of 2024, Britain’s economy is 5 percent worse off now than it would have been had it stayed in the EU.

2020 - 2021

COVID-19 Spreads, Killing Millions

In January 2020, the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in Europe. The virus then began to spread from Northern Italy across the continent—appearing in Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Russia, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. In Italy, Europe’s first serious outbreak, the government issued a country-wide lockdown. Neighboring countries soon closed their borders. Lockdowns and school closures followed across Europe. The virus infected millions, including heads of state like the United Kingdom’s Prime Minister. Within months, one hundred thousand Europeans had died from the virus. Over the following years, the death toll would climb to over two million. The COVID-19 pandemic had a large and far-reaching effect—both on European life and the region’s economy. The pandemic proved even more costly than the 2008 financial crisis, leading to just over a 6 percent drop in the EU’s GDP. One outcome of the pandemic, however, may have been greater European integration. The EU approved the largest stimulus package in European history, which would operate between 2021 and 2026. The plan is designed to make Europe more resilient by preparing for future health risks as well as fighting climate change.

2022

Russia Invades Ukraine: Europe’s Biggest Conflict Since World War II

Under Vladimir Putin, Russia has tried to reassert influence over former Soviet countries, many of which have sought closer ties with the West. Ukraine quickly became the focal point of these efforts. This was for several reasons: Russia and Ukraine share close cultural and historical ties—which Putin has used to claim Ukraine should not be an independent country. Geographically, Putin has argued that Ukraine represents a strategic buffer between Russia and an adversarial West. Politically and economically, Ukraine was also the most powerful former Soviet Republic after Russia, making its increasingly Westward orientation an even greater threat. After annexing Crimea and supporting separatists in 2014, Russia mounted a full-scale invasion in 2022. But Ukrainians fought back, repelling the initial invasion. Meanwhile, Europe and the United States enacted sweeping sanctions on Russia, which have caused economic uncertainty and threatened energy security—since many countries relied on Russian oil and gas imports. As the war drags on, European countries face difficult questions: Do they keep sending military aid to Ukraine? Do they push for peace negotiations with Russia? Or do they take more drastic measures, like fast-tracking Ukrainian membership into the EU, NATO, or both? Not since World War II has Europe seen such destruction and death. The war remains both NATO’s and Europe’s largest test to date.