The Race to Develop COVID-19 Vaccines

How did scientists produce the COVID-19 vaccines in record time? Explore how health innovations, like the mRNA vaccine, are invented and how they impact global health today.

Between January and July 2021, daily COVID-19 infections in the United States dropped from over three hundred thousand to fewer than five thousand. This steep decline represented an encouraging achievement in the global war against COVID-19.

No single tool can claim complete credit for turning the tide, but vaccines were a major contributing factor. The first U.S. COVID-19 vaccines began rollout in December 2020 following the fastest vaccine development in history.

Since then, several new vaccines have been launched on the global market. As of August 2021, nearly five billion doses have been administered worldwide. Most have gone to a handful of countries, including the United States, Brazil, China, India, and Japan.

Although vaccination efforts have helped countries counter COVID-19, they haven't eliminated outbreaks, and the threat of new COVID-19 variants looms. But let’s back up a bit. How did the United States develop and deploy multiple COVID-19 vaccines faster than any other vaccine in history?

How long does it take to invent a vaccine?

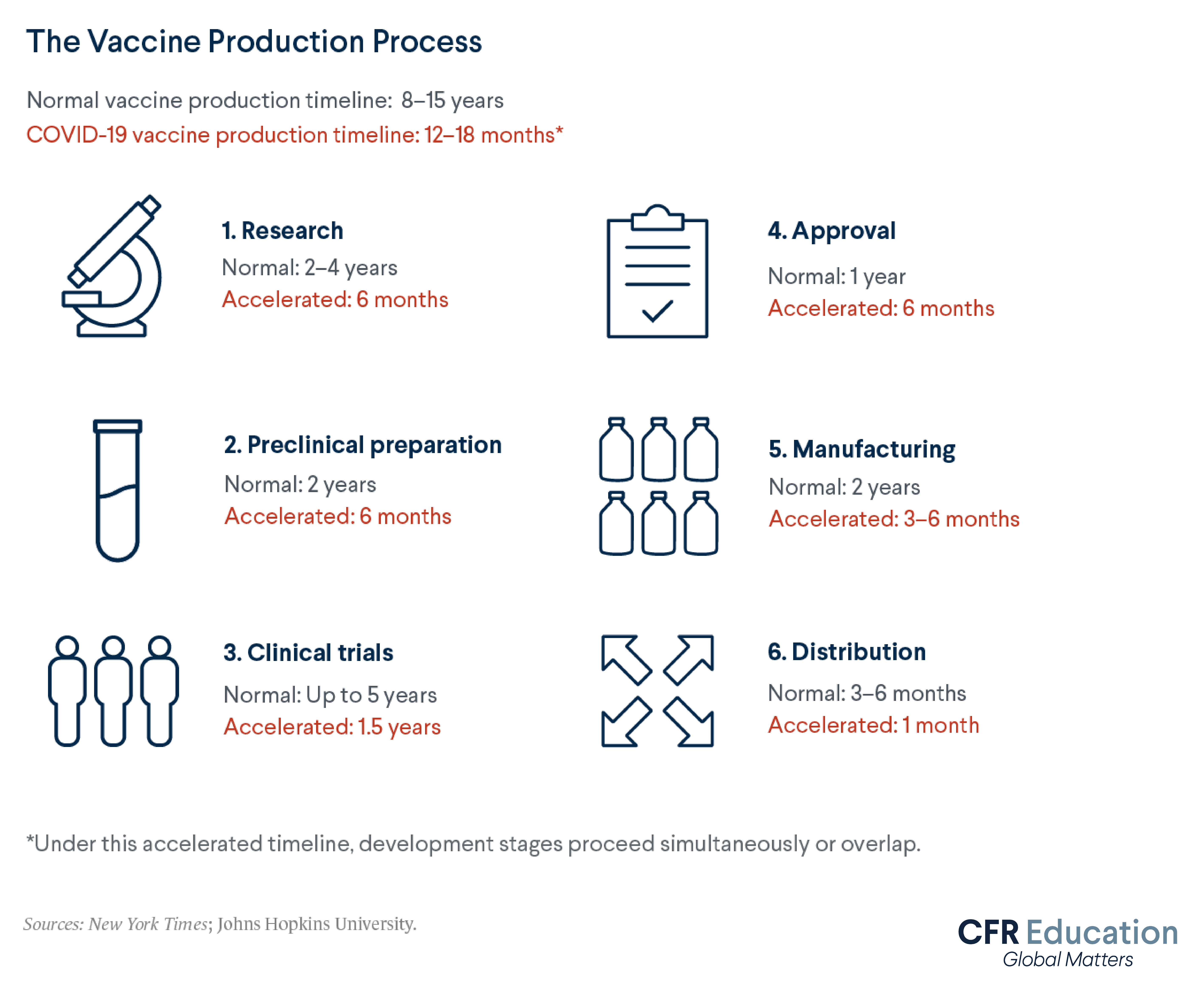

Inventing new vaccines typically takes eight to fifteen years and involves several steps. These steps include research, clinical trials, regulatory approval, and manufacturing and distribution. The United States’ initial three COVID-19 vaccines proceeded through all these stages in just one year. Let’s explore how.

How are vaccines researched and developed?

The United States’ first COVID-19 vaccines were developed by Johnson & Johnson, Moderna, and Pfizer-BioNTech.

The U.S. government pumped nearly $1.5 billion into Johnson & Johnson’s and Moderna’s vaccine development processes as part of a program called Operation Warp Speed. Meanwhile, Pfizer’s German partner BioNTech accepted $445 million from the German government to develop a vaccine.

Upfront funding helped make vaccine development a safer financial bet. This backing allowed companies to gamble on sending vaccines to clinical trials that could prove ineffective. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the U.S. government also hedged its bets, granting seven companies nearly $20 billion in financing for vaccines and treatments for COVID-19. These funds were provided with the understanding that not all those companies would necessarily succeed.

Vaccine development companies also benefited from valuable pre existing research. Scientists have been studying coronaviruses—the same culprits behind the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic. Scientists had also been studying the 2012 outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)—for decades. Knowledge gained from these past outbreaks gave them a jump on designing the best vaccine for fighting COVID-19.

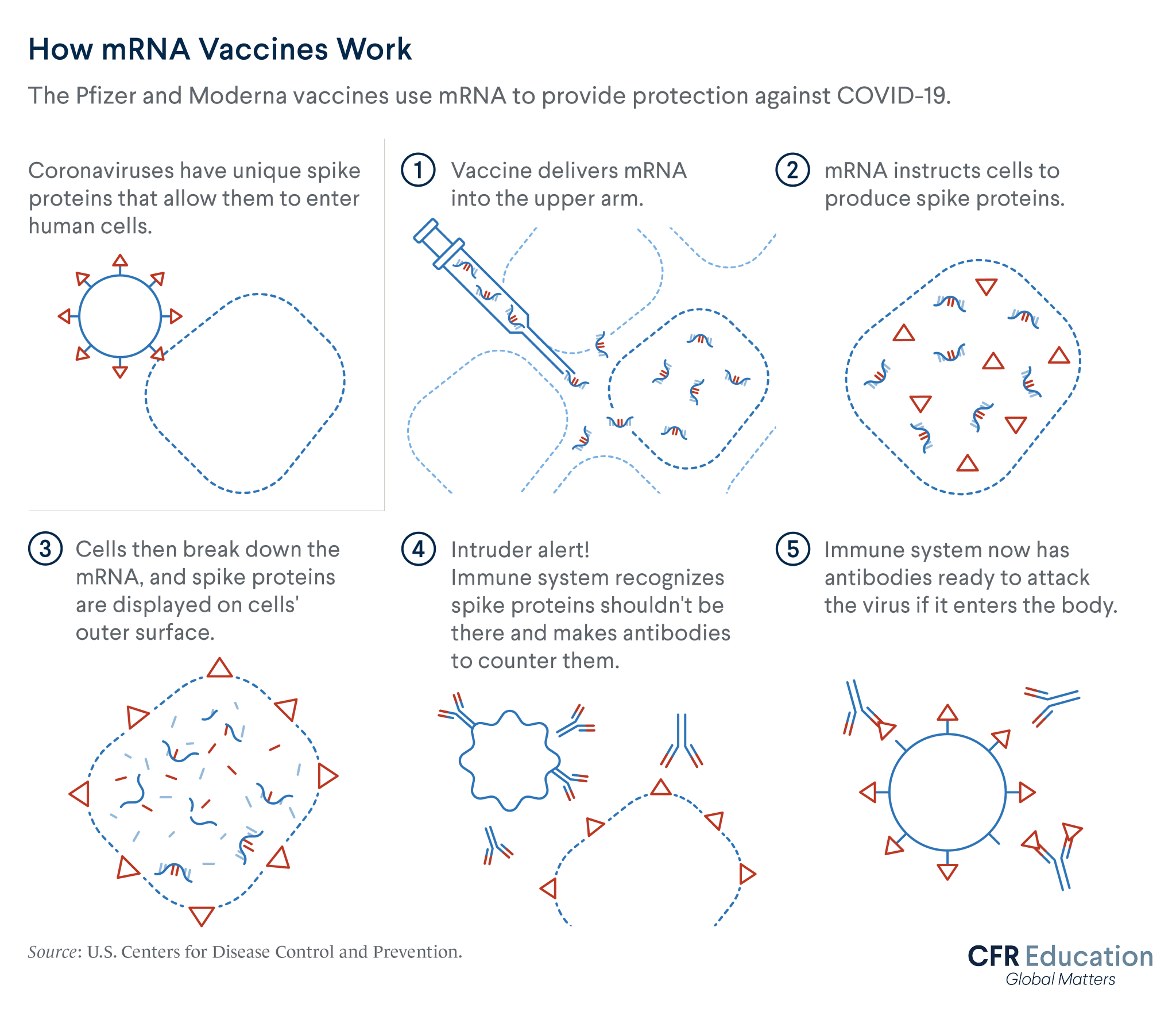

Meanwhile, new messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccine technology aided Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech's speedy development. This technology has been under development for decades. It differs from traditional vaccines, which inject weakened or dead versions of viruses into people’s bodies to provoke immune responses. By contrast, Moderna’s and Pfizer-BioNTech’s vaccines use mRNA. This molecule operates like an instruction manual to help the immune system produce proteins that defend the body against future COVID-19 exposures.

This upfront funding, prior research, and new technology led to the development of test COVID-19 vaccines in just weeks—even before the World Health Organization’s (WHO) labeled the coronavirus crisis a global pandemic on March 11, 2020.

What are vaccine clinical trials?

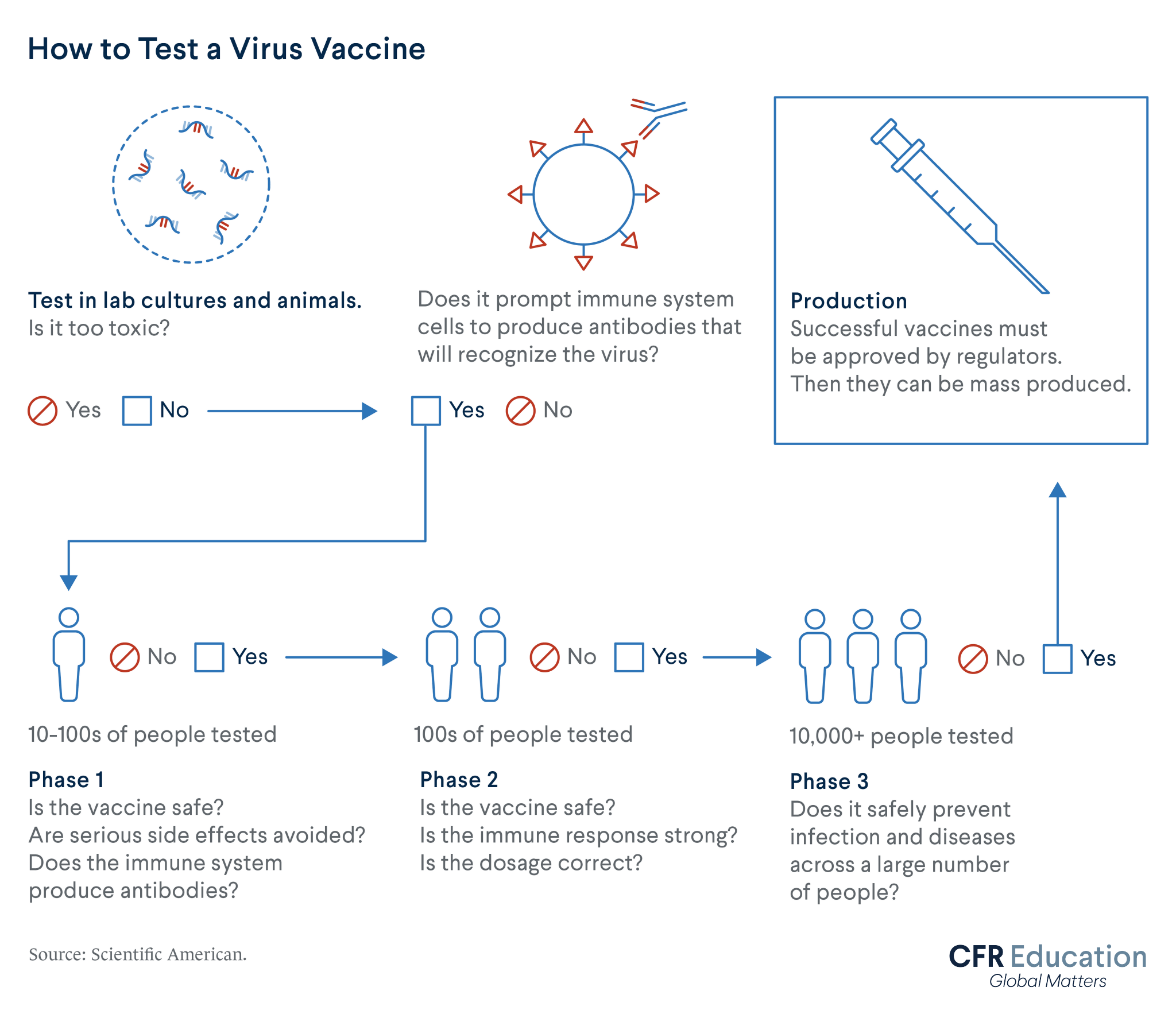

Clinical trials are crucial indicators of whether a vaccine works as intended. These tests usually progress through three phases. As the phases progress, the number of volunteers increases from dozens to thousands of people.

Clinical trials record the different outcomes, such as rates of illness with COVID-19, between groups of people given test vaccines versus placebos. Trials also determine whether a vaccine will cause severe side effects.

Usually, the three stages of clinical trials proceed one at a time. But faced with the escalating COVID-19 crisis in 2020, developers ran overlapping trials for test vaccines. This accelerated the overall timeline. Although clinical trials typically take up to five years, companies completed trials for the COVID-19 vaccines in under one year.

Data from those trials revealed that the COVID-19 vaccines work remarkably well and serious side effects are extremely rare.

As of August 2021, new clinical trials are ongoing, with tests gathering data on outcomes such as vaccine efficacy and safety for children.

How does a vaccine get approved?

Once a vaccine candidate graduates from trials, its makers seek approval from a regulatory agency before selling it to consumers. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the national regulatory authority. The agency’s approval process typically takes several months.

Before approval, a vaccine manufacturer can request what’s called emergency use authorization (EUA). This allows not-yet-approved drugs to go to market. EUAs require the FDA to weigh whether a vaccine’s benefits exceed any risks, using data from at least one phase-three clinical trial.

The FDA granted Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna EUAs in December 2020. This marked the start of the U.S. COVID-19 vaccine distribution. Johnson & Johnson’s EUA followed in February 2021.

In August 2021, the FDA fully approved Pfizer-BioNTech’s vaccine for use in anyone aged sixteen or older. That same month, Moderna announced it had submitted its application for full FDA approval for anyone aged eighteen or older.

How are vaccines manufactured and distributed?

Usually, vaccines need to wait for full FDA approval before manufacturers begin producing them for the public. However, given the accelerated timeline of the COVID-19 vaccine development process, U.S. companies ramped up manufacturing while their vaccines were still in trials. The U.S. government similarly began pumping money into manufacturing prospective doses before regulatory approval.

Under Operation Warp Speed, the U.S. government awarded Johnson & Johnson, Moderna, and Pfizer-BioNTech nearly $5 billion in July and August 2020. These funds were granted to produce three hundred million vaccine doses, contingent on regulatory approval and proof of safety and efficacy. Since then, those contracts have expanded to include production of hundreds of millions more doses.

When Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech began vaccinating people in December 2020, supplies of the shot were extremely limited. This led health experts to recommend vaccinating certain groups—such as frontline health-care workers—first. The pool of those eligible for shots has since expanded. As of August 2021, COVID-19 vaccines are available to all U.S. residents over the age of eighteen. Pfizer-BioNTech’s shot was approved for those over the age of twelve.

Although access to the vaccine has greatly increased, not every American has been vaccinated. Vaccine hesitancy, which stems from factors including distrust of medical and government authorities as well as misinformation over vaccine efficacy and safety, has helped drive health disparities between the United States’ vaccinated and unvaccinated populations.

The Future of Vaccines

Before 2021, the fastest-ever timeline for producing a vaccine was four years. COVID-19 vaccines shattered this record. These crucial weapons against the coronavirus crisis took just one year to research, design, create, and deliver.

The development of these critical tools on such an accelerated timeline represents a major leap in the world’s history of medicine, and their potential does not stop with COVID-19. For instance, experts speculate that mRNA technologies harnessed for COVID-19 shots could soon be used to develop vaccines and treatments for diseases such as hepatitis B, malaria, tuberculosis—and even cancer.

But as health experts contemplated the future of vaccines, barriers remained to vaccinating the global population against COVID-19. These challenges include unequal access to vaccine doses. According to the WHO, nearly 60 percent of people in high-income countries had received at least one COVID-19 vaccine shot by September 2021. For low-income countries, this measure stood at less than 3 percent.

In 2021, the future of the world’s COVID-19 vaccines is encouraging but uncertain. Debates over booster shots and disease variants continue to dominate headlines. With scientists and experts learning new information every day, understanding how the vaccine fits in with the rest of the tools available in the world’s medical kit—tools that scale from washing hands to locking down entire countries—remains critical to countering the COVID-19 crisis.