Essential Events Since 1945

From the Cold War and decolonization to globalization, learn how recent historical developments shaped today’s world.

World History Timeline: 1944-Present

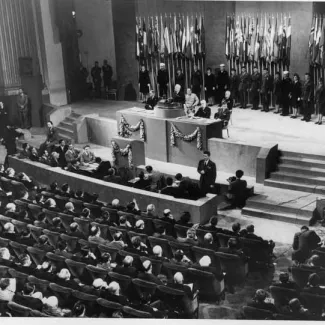

Liberal World Order Promotes Global Cooperation Following World War II

Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials Shape Modern Human Rights Canon

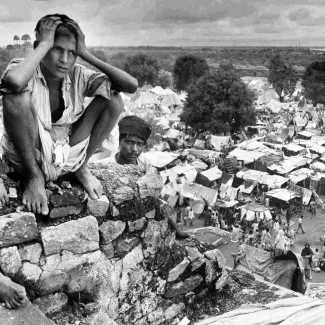

Partition Divides India and Pakistan Along Religious Lines

United States Helps Rebuild Postwar Europe Through Marshall Plan

Creation of Israel Divides Middle East

NATO Offers Western Europe Security Amid Cold War

Detonation of First Soviet Atomic Bomb Sparks Nuclear Arms Race

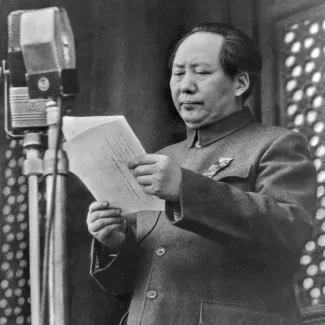

Chinese Civil War Brings Communists to Power in Beijing

Korean War Leaves a Peninsula Divided

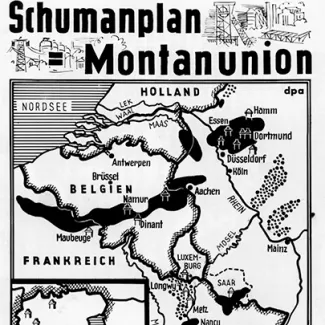

European Coal and Steel Community Offers New Approach to Lasting Peace

U.S. Civil Rights Movement Kicks Off Decades of Protest, Reforms

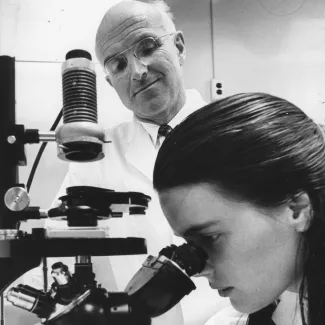

First Successful Organ Transplant Advances Lifesaving Medical Technology

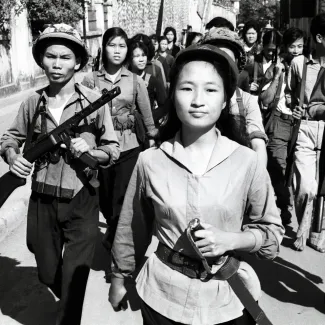

United States and Soviet Union Wage Proxy War in Vietnam

First Container Ship Transforms Global Shipping Industry

Suez Crisis Becomes Flashpoint in Cold War

Ghana Gains Independence Amid Massive Wave of Decolonization

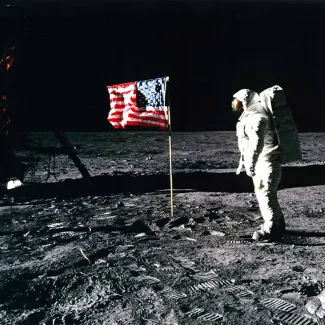

Space Race Sends Cold War Competition to New Heights

Sirimavo Bandaranaike Makes History as First Woman Elected Head of Government

Cuban Missile Crisis Brings World to Brink of Nuclear War

Six Day War Redefines Middle East’s Balance of Power

Japan Becomes World’s Second-Largest Economy, Driving Asia’s Economic Miracle

Cold War Sparks Birth of Internet

Nixon’s Visit to Beijing Restarts U.S.-China Relations

Camp David Accords Provide Glimmer of Peace Between Israel and Arab World

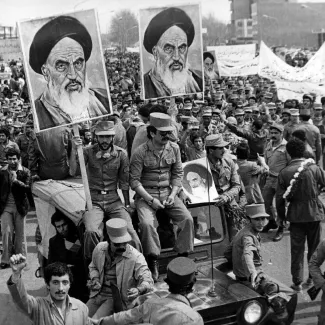

Iranian Revolution Leads to Severed Ties With United States

As the Soviet Union Falls, Liberal Democracy Rises

Tiananmen Square Massacre Demonstrates China’s Intolerance of Dissent

United States Leads International Coalition to Liberate Kuwait

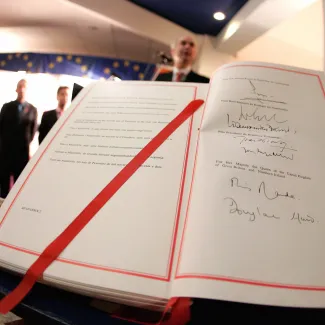

Maastricht Treaty Lays Foundation for European Union

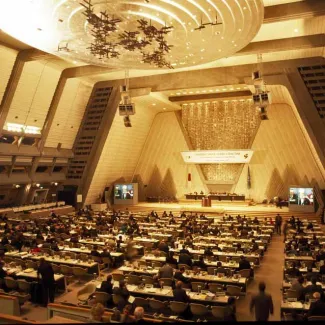

Countries Promote Global Cooperation on Climate Change

Oslo Accords Offer Chance for Arab-Israeli Peace

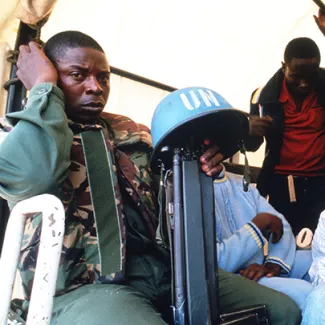

World Fails to Respond to Rwandan Genocide

NAFTA Serves as Marquee Free Trade Agreement for Americas

Nelson Mandela Elected South Africa’s First Black President

United States Transfers Panama Canal to Panamanian Control

9/11 Attacks Lead United States to Launch Two Wars

Computer Worm Ushers in Era of Cyberattacks

Arab Spring Topples Governments, Falls Short of Widespread Reform

Belt and Road Initiative Reflects China’s Vision for Future

COVID-19 Declared a Global Pandemic

Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum

At the end of World War II, the United States and its allies created a series of international organizations and agreements to promote global peace and prosperity. These institutions included the United Nations, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (a forerunner to today’s World Trade Organization). For decades, this U.S.-led international system—known as the liberal world order—has promoted global cooperation on issues including security, trade, development, health, and monetary policy. The liberal world order is perpetuated and secured by the United States’ military strength and global network of alliances. But recently, this system has struggled to address both new and familiar sources of disorder. The abuse of cyberspace, the impacts of climate change, the spread of COVID-19, the ongoing threat of nuclear proliferation, and the rise of protectionism all threaten global stability. Moreover, countries like China have made a concerted effort to upend the liberal world order and create parallel institutions of their own.

National Archives

From the horrors of World War II and the Holocaust came a new chapter in international human rights. In two marquee cases—the Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials—the victors of the war prosecuted German and Japanese leaders for atrocities committed during the conflict. These trials represented the first major efforts to prosecute crimes, including genocide, that occurred across several countries. Legal efforts to establish accountability during war inspired the creation of several foundational human rights agreements including the 1948 Genocide Convention, the 1950 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the 1950 Nuremberg Principles. These documents established guidelines for defining war crimes and frameworks for defending human rights.

Photo12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The origins of today’s rivalry between India and Pakistan—two nuclear-armed nations—can be found in a painful chapter of history known as partition. In 1947, Britain departed its long-held colony on the subcontinent and divided it into two independent countries: Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan. In the months following this separation, millions of Muslims migrated to Pakistan and millions of Hindus and Sikhs fled to India. All told, around fifteen million people migrated and over a million died in the ensuing violence. Since the trauma of partition, the two countries have maintained a deep mutual mistrust and have fought three major wars. One conflict in 1971 resulted in the creation of Bangladesh, which had previously been part of Pakistan. Other conflicts have been waged over the contested region of Kashmir.

Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis via Getty Images

The United States resolved to assist Europe after World War II rather than retreat across the Atlantic as it did following World War I. Thus, in 1948, the United States launched a multibillion-dollar plan to provide aid to any European country trying to rebuild its economy. The Marshall Plan was not merely charity: it was a cornerstone of U.S. Cold War strategy. The United States believed that Europe’s physical, economic, and political collapse made it vulnerable to encroaching Soviet influence. In providing aid, the United States sought to stave off the spread of communism while shoring up its democratic allies. Sure enough, each of the sixteen west European countries that accepted funds experienced rapid economic recovery and deepened relations with the United States. The Soviet Union and east European countries, on the other hand, rejected the aid, fearing it would give the United States influence over their economies. Instead, the Soviet Union offered east European countries aid through an initiative known as the Molotov Plan. The USSR also created the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) to coordinate its bloc’s economic development.

Government Press Office of Israel

Following World War II and the horrors of the Holocaust, Jewish leaders in British-ruled Palestine pushed for the establishment of a Jewish state. To force the issue, Zionist underground groups resorted to violence against the British after independence was not immediately granted. Following this upheaval, the United Nations announced in 1947 that Palestine would be partitioned into separate Jewish and Arab countries. Jewish leaders declared Israel’s independence upon Britain’s withdrawal in May 1948. Arabs, however, rejected the UN partition plan, which—in their view—seized their ancestral lands. Neighboring Arab countries invaded Israel to defend the Palestinian Arabs but were ultimately defeated. Although Israelis refer to this conflict as their War of Independence, Arabs know it as the Nakba (Arabic for “catastrophe”). The war was devastating to Arabs because hundreds of thousands of Palestinians fled their homes and lost additional land. In the ensuing decades, Israel and its Arab neighbors fought several wars, including a conflict in 1967. Known as the Six-Day War, this conflict shifted the balance of power and redrew borders within the Middle East. Today, the Palestinian issue remains unresolved; however, in recent years, the common threat that Israel and its Arab neighbors feel from Iran has led more countries to begin a process of normalizing relations.

National Archives

In 1949, the United States, Canada, and ten European countries formed a military alliance known as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The initial purpose of this alliance was to preserve a free and democratic Europe, particularly against challenges from the Soviet Union. This groundbreaking peacetime alliance made the United States—with its outsized military strength—effectively the co-defender of Western Europe. The cornerstone of this alliance was mutual security. Members are required to pledge that an attack on one country would be treated as an attack on all. In 1955, NATO admitted West Germany as a new member, and in response, the Soviet Union created its own regional alliance, the Warsaw Pact, which included the Soviet satellite states in Eastern Europe. Despite tensions that occasionally flared, the Cold War stayed cold in Europe. The power of NATO and the threat of nuclear war effectively deterred armed conflict on the continent. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, NATO has expanded (now numbering thirty member countries) and begun confronting new forms of instability outside its members’ borders.

Sovfoto/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The Cold War entered a dangerous new chapter in 1949 when the Soviet Union became the second country to develop an atomic bomb, four years after the United States. Now that two rivals had nuclear weapons, the stakes of any Cold War confrontation dramatically increased. However, those weapons, perhaps counterintuitively, functioned as a deterrent to conflict; both sides recognized that using nuclear arms would result in equally devastating retaliation—a concept known as mutually assured destruction (or MAD). Although this deterrence helped keep the Cold War cold, any misstep could have resulted in unprecedented devastation. Today, nine countries are known or believed to possess nuclear weapons: the United States, China, France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, and the United Kingdom.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

In 1912, the ailing Qing dynasty was replaced by the Republic of China, headed by the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, or KMT). Led by Chiang Kai-shek, the KMT oversaw an authoritarian government and sought to stitch together a country that had fractured into territories run by warlords. Soon, however, it had to contend with a challenge from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), led by Mao Zedong. Mao sought to lead a workers’ revolution and establish a communist government. A brutal civil war ensued, dividing China from 1927 to 1949. After more than twenty years of fighting and millions of deaths, the CCP emerged victorious. On October 1, 1949, Mao declared the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, which the Communist Party rules to this day. The KMT fled to the island of Taiwan. Now, seventy years later, a deep political rift remains; mainland China views Taiwan as a renegade province that needs to be brought under its control. Meanwhile, Taiwan has developed a flourishing democracy and successful economy free of CCP influence. Taipei has sought to strengthen ties with the United States to ensure its security. However, to maintain interests in the region, the United States has maintained a policy of ambiguity on whether it would defend Taiwan should China attack it.

National Archives

North and South Korea share a border, a language, and over a thousand years of history as one united Korea. But, today, the two countries could not be more dissimilar. South Korea is a vibrant democracy and an economic powerhouse. Meanwhile, North Korea is an isolated, impoverished country run by one of the world’s most repressive governments. The split dates back to the end of World War II when the United States and the Soviet Union divided the peninsula; this partition formed a communist government in the north and a capitalist one in the south. The division of the peninsula was intended to be temporary, but in 1950, North Korea (with Soviet and Chinese backing) invaded the south, starting the Korean War. Fearing a communist takeover of the entire peninsula, the United States led a UN coalition that came to South Korea’s defense. After three years of fighting in which millions died, the two sides laid down their arms—but the peninsula remained divided. The two Koreas technically remain at war to this day.

DPA/Picture Alliance via Getty Images

European leaders knew that the economic reintegration of West Germany was crucial to build a peaceful Europe and forge a united front against the Soviet Union. But given the enduring trauma of World War II, a strong Germany still inspired fear, especially in its next door neighbor and historical rival, France. In 1950, France’s foreign minister proposed a simple solution: France and Germany could share the coal and steel resources in the region between the two countries. By setting up a common market, a kind of trade bloc in which countries agree to remove most barriers to trade (like tariffs), the European Coal and Steel Community created economic benefits for any European country interested in joining. (Ultimately, it had six members.) More importantly, it would make going to war—preparations for which depended on coal and steel for weapons and ammunition—simply too expensive and impossible to plan covertly. This economic union, the first step to European postwar integration, was designed to create a lasting peace. The European Coal and Steel Community is seen as the forerunner to the European Commission and the European Union.

National Archives

Although the United States’ Declaration of Independence asserts that “all men are created equal,” the nation has struggled to live up to its founding creed. Centuries of U.S. laws, norms, and institutions have produced dramatically different experiences for Americans based on factors such as race, religion, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and disability status. In the 1950s and 1960s, political activism and several landmark legal victories began to chip away at these discriminatory policies. In 1954, the Supreme Court decided in Brown v. Board of Education that public school segregation was illegal. Meanwhile, the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act secured legal protections against discrimination based on race. This civil rights movement inspired decades of mass mobilization—not just in the United States but around the world—and has fueled ongoing efforts to secure equal rights for all Americans. This process is still ongoing; for example, racial justice has been at the front of American consciousness in the wake of the 2020 police killing of George Floyd.

Elizabeth Jones/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

On December 23, 1954, Joseph Murray performed the first successful organ transplant on identical twins. This procedure has since saved thousands of lives and is just one of the many medical breakthroughs over the past seventy-five years. Since the end of World War II, scientists have invented pacemakers, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machines, the measles vaccine, and many more lifesaving interventions. As a result, public health has dramatically improved. Between 1950 and 2015 average global life expectancy jumped from forty-six to seventy-two years. However, health-related inequalities persist: in low-income countries, for example, infant mortality rates are 70 percent higher than the global average. Moreover,life expectancy in low-income countries is ten years lower than the global average and thousands more people die from treatable diseases such as polio and cholera.

Romano Cagnoni/Getty Images

Throughout the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union supported opposing factions in conflicts around the world, including in places such as Afghanistan, Korea, and Nicaragua. Among the costliest of these conflicts—also known as proxy wars—took place in Vietnam. After a nine-year war of independence against France, Vietnam split into two countries: a Chinese- and Soviet-backed north and a U.S.-backed south. When North Vietnam invaded the south in 1955, the United States, China, and Russia ratcheted up their support for the respective sides. All three nations sent significant financial aid, weapons, and soldiers, which fueled a devastating, two-decade conflict. Years of brutal battles culminated in the withdrawal of U.S. forces and the signing of the Paris Peace Accords in 1973; the United States evacuated its personnel in 1975. More than two million Vietnamese civilians are estimated to have died in the war, which resulted in communist control over a unified country. The war was also costly for the United States, claiming fifty-eight thousand American lives and costing billions of dollars. The war also sparked mass political protests in the United States, rupturing many Americans’ trust in their military and government.

Reuters

For centuries, global trade was conducted by ships loaded—often haphazardly—with crates, boxes, and packages of all sizes. But this system changed forever in 1956 when the first container ship left Newark, New Jersey, with fifty-eight standardized shipping containers on board. Shipping containers soon became the accepted unit of global trade. These rectangular trailers could be stacked neatly on board massive ships and unloaded by machines directly onto trucks. (In the past, dockworkers had to unload hundreds of thousands of items by hand.) Using shipping containers globally has dramatically slashed the costs of shipping and, thus, the prices of goods. One study found that containerization correlated with a nearly 800 percent increase in trade over twenty years. Today, modern container ships can stretch over four football fields, allowing for greater and cheaper movement of goods than ever before.

Bettmann/Getty Images

During the Cold War, U.S. officials were eager for anything that might erode the world’s opinion of the Soviet Union. Evidence presented itself in 1956 when Hungarian citizens overthrew their communist government. The Soviet Union responded by sending its military to brutally crush the revolution. U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower pointed to the bloodshed in Hungary as a prime example of Soviet repression. But, at the same time, an event in the Middle East undermined the United States’ Cold War messaging. Britain, France, and Israel unexpectedly invaded Egypt in a bid to retake the country’s strategic Suez Canal. U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower was furious that the invasion distracted the world’s attention from the anti-communist uprising in Hungary. The invasion also threatened to push the Arab world even closer to the Soviet Union, undermining U.S. interests in the Middle East. Ultimately, President Eisenhower compelled Britain and France to withdraw from Egypt and pledged the United States would provide financial and military support to Middle Eastern countries under the threat of outside aggression. Aid was a last ditch effort to ensure that the Soviet Union could not expand its influence in the region.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Ghana, formerly known as the Gold Coast, gained its independence in 1957, becoming the first sub-Saharan country to break free of colonial rule. It would not be the last. In the decades following World War II, dozens of countries across Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, the Middle East, and the Pacific gained their independence. This movement brought an end to an age of colonialism in which mostly European empires ruled over nearly a third of the world’s population. This period, known as the era of decolonization, fundamentally reshaped the world. Between 1945 and 1989, roughly a hundred countries came into existence. But for those former colonies that gained their independence, establishing a country entailed far more than simply flying a new flag or playing a national anthem. The process of breaking away from colonial rule often entailed years of violence or protest. Even after independence, leaders still struggle to build governments that provide their citizens with physical and economic security along with political rights.

Reuters

The Cold War was not just a war of weapons; it was also a war of narratives. In arts, culture, science, and sports, the United States and the Soviet Union competed to convince the world of their superiority. Hollywood, the Olympics, and even chess competitions became cultural battlefields for the two superpowers. Arguably, the Cold War’s highest-profile competition occurred in outer space. The so-called space race, which lasted from the 1950s through the early 1970s, saw the United States and the Soviet Union compete to achieve a series of milestones. The Soviet Union scored early victories, sending the first satellite into space (the Soviet Sputnik I in 1957) and the first person into orbit (Yuri Gagarin in 1961). However, the United States delivered a defining blow by successfully sending humans to walk on the moon (American astronaut Neil Armstrong in 1969). Fears of falling behind in this competition helped galvanize massive federal spending to overhaul mathematics, foreign language, and science curricula in U.S. schools.

Keystone/Hulton Archive via Getty Images

Although history has its memorable women rulers—like ancient Egypt’s Cleopatra and Russia’s Catherine the Great—female leadership has until recently been a rarity in modern politics. But in 1960, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) elected the world’s first female head of government, Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike. Within years of that election, women ascended to power around the globe: India and Israel elected their first women prime ministers in 1966 and 1969. In 1974, Argentina elected the world’s first woman president, Isabel Martinez de Peron. In 2020, Kamala Harris made history as the first woman elected vice president of the United States; however, the country has yet to elect a woman president. As of April 2021, 22 of the 193 UN Member states have women heads of state or government.

Cecil Stoughton/White House via John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

Potentially the closest the world has come to nuclear war took place in a thirteen-day standoff known as the Cuban Missile Crisis. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev largely pursued a policy of peaceful coexistence with the West, but in 1962, American intelligence discovered Soviet-built missile sites in Cuba. The Soviet Union insisted these sites were strictly to defend Cuba from American interference. The United States argued that Soviet nuclear weapons less than one hundred miles from U.S. soil posed a direct and immediate threat to American national security. President John F. Kennedy faced a difficult choice: invading Cuba could trigger a nuclear response, but inaction could allow further Soviet buildup on the island. Instead, Kennedy ordered a naval quarantine of Cuba, which Khrushchev considered an act of aggression. However, Khrushchev ultimately opted to back down rather than risk a nuclear exchange, and the two leaders reached a compromise: the Soviets would remove their missiles from Cuba in exchange for the United States secretly doing the same in Turkey and publicly promising not to invade Cuba. In the wake of the crisis, the United States and the Soviet Union experienced a détente phase—a period of easing tensions during which the two countries pursued a series of arms control agreements throughout the 1960s and 1970s that helped reduce the risk of nuclear conflict.

Government Press Office of Israel

As a small country surrounded by hostile neighbors, Israel has worried about its security since its founding. By 1967, Israel had already fought two wars (over independence in 1948 and against Egypt in 1956), and Israelis feared that a third conflict was imminent. Egypt’s then President Gamal Abdel Nasser repeatedly promised to avenge displaced Palestinians and was parading troops and tanks through the streets of Cairo. In response, Israel launched a preemptive attack against its Arab neighbors on June 5, 1967. These strikes destroyed the air forces of Egypt, Jordan, and Syria, paving the way for rapid Israeli ground advances. By June 10, the land Israel controlled had tripled in size, as it took over Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula to the banks of the Suez Canal, Syria’s Golan Heights, and the territories of East Jerusalem, the Gaza Strip, and the West Bank. Known as the Six Day War, this conflict redrew borders within the Middle East, established Israel as the region’s dominant military power, dealt a devastating blow to Arab armies, and exacerbated the numbers and plight of Palestinian refugees.

Bettmann via Getty Images

In the twentieth century, several East Asian countries pulled off an economic transformation so dramatic that many economists called it a miracle. Looking to rebuild after World War II, Japan developed its manufacturing sector, emphasized exports, and invested in education and infrastructure. These reforms, along with the introduction of strong labor laws and the overhaul of its old feudal system, set Japan on a trajectory of spectacular growth and took it from the ninth-largest world economy in 1950 to the second largest by 1968. Japan set the standard, and Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan—dubbed the Four Asian Tigers—followed suit, drawing inspiration from the Japanese policies that sparked unprecedented growth. Today, these Asian countries enjoy high standards of living and are home to some of the world’s largest companies, like Toyota and Honda in Japan and Samsung in South Korea.

Fred Prouser/Reuters

Today, we use the internet for just about everything: ordering food, talking with friends, and working remotely during a pandemic. But did you know the internet has its origins in the Cold War? Concerned the Soviets would bring down U.S. telephone networks during a conflict, researchers at the U.S. Department of Defense and at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) developed a closed network via which computers could communicate. By 1969, researchers had connected four computers to what was then called the ARPANET, and in 1971, email allowed computers on the network to communicate with each other. Two years later, mobile communications experienced a new milestone with the first call from a cell phone. That phone weighed over two pounds, had a talk time of just thirty minutes, and took a year to recharge—a far cry from today’s smartphones. Likewise, the internet has dramatically changed over the past half century, expanding from just four computers in 1969 to around four billion users worldwide in 2018.

Reuters

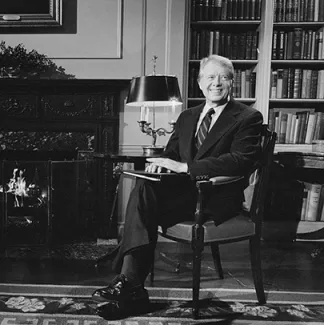

After the Chinese Civil War, the United States refused to recognize Mao Zedong’s communist government. Instead, the United States cooperated with the newly exiled government in Taiwan, a strong anti-communist ally. But in 1972, Richard Nixon shocked the world by becoming the first sitting U.S. president to visit mainland China, in an effort to establish relations between the two countries. Nixon warmed up to Mao’s China largely to take advantage of the increasingly troubled relationship between China and the Soviet Union and to weaken the link between China and North Vietnam. Ultimately, the United States formally recognized mainland China (and reduced relations with Taiwan) in 1979 under President Jimmy Carter. The Taiwan Relations Act of the same year, however, promised the U.S. government would “consider any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means of grave concern to the United States.” Today, the United States sells advanced weapons to Taiwan, while also maintaining a policy of ambiguity on whether it would defend Taiwan with force should China attack it. This tricky diplomatic dance is just one aspect of U.S.-Chinese relations, which in recent years have seen increased tensions over issues such as trade, intellectual property, human rights, Hong Kong sovereignty, and territorial claims in the South and East China Seas.

National Archives

Following the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger brokered a series of agreements, laying the foundations to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict and remove the tension between America’s interests in Israel’s survival and good relations with Arab oil producers (notably Saudi Arabia). In 1978, President Jimmy Carter built on these foundations to promote a breakthrough to peace between Egypt and Israel. While Egypt deeply distrusted Israel, it saw a peace deal as an opportunity to regain the territory it lost in the 1967 Six Day War, improve relations with the United States, and boost its struggling economy. President Carter invited both countries’ leaders to the United States for two weeks of secret negotiations that culminated in the Camp David Accords—a landmark peace treaty between the two formerly bitter rivals. This agreement removed the largest and most militarily powerful Arab country from the conflict with Israel. For decades, U.S. administrations have sought to replicate the success at Camp David, and, today, five other Arab countries—Bahrain, Jordan, Morocco, Sudan, and the United Arab Emirates—have established formal diplomatic relations with Israel.

Keystone/Getty Images

Today, Iran is the United States’ fiercest rival in the Middle East. But for most of the twentieth century, the two were close partners with common interests in regional security and oil. In 1953, the CIA even backed a coup in Iran that overthrew a democratically elected prime minister to keep the shah—the hereditary leader of Iran and a U.S. ally—in power. Many Iranians, however, saw the shah as a corrupt American puppet whose secret police tortured and imprisoned dissidents. This frustration culminated in the 1979 Islamic Revolution. This movement successfully toppled the shah and brought to power a fiercely anti-Western government—one composed of political, military, and religious leaders. The revolution culminated with the appointment of Ruhollah Khomeini, a formerly exiled cleric and staunch enemy to American regional interests, as the supreme religious leader of the newly established islamic state. Soon after the revolution, Iranian university students stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, taking American staff hostage for 444 days. The crisis resulted not only in American sanctions on Iran but also the severing of diplomatic relations. Today, diplomatic ties between Washington and Tehran remain suspended.

David Brauchli/Reuters

In the late 1980s, the Soviet Union was on the brink of collapse. The country’s economy was creaking under the strain of a costly military intervention in Afghanistan initiated in December 1979. Meanwhile, domestic problems—including the Chernobyl nuclear meltdown—led to outrage among Soviet citizens, who felt empowered to voice frustrations thanks to political reforms by Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev. These factors, among many others, led to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. The complete breakup of the Soviet Union followed in 1991. After nearly half a century, the Cold War ended in a triumphant moment for the U.S.-led Western alliance. From the ashes of the Soviet Union arose more than a dozen new democracies; indeed, the world appeared to be on the cusp of a new era defined by peace, liberal democracy, and free trade. But since 2005, the world has become less free and democratic every year in a concerning trend known as democratic backsliding.

Arthur Tsang/Reuters

In the 1980s, hundreds of millions of people in China escaped extreme poverty through the country’s economic reforms. Nevertheless, vast inequality, rising food prices, and government corruption remained. These concerns boiled over in Beijing in May 1989. Students across China poured out into the streets demanding freedom of speech, democratic reforms, and an end to corruption among Communist Party elites. After negotiations with protesters failed, the government declared martial law and sent hundreds of thousands of troops to confront nearly one million students who were demonstrating in the iconic Tiananmen Square. When protesters refused to leave, the government opened fire, killing hundreds—if not thousands—of civilians in the square and surrounding streets. The message from the Communist Party to the people was clear: political dissent would not be tolerated. The massacre remains one of the country’s most politically sensitive and censored events. All web searches originating in China that have to do with the incident are blocked; many young Chinese people are unaware it ever happened.

Allan Tannenbaum/Getty Images

Following the Iraqi invasion of Iran in 1980 and the devastating eight-year war that followed, Iraq once again invaded a neighboring country in 1990—this time annexing Kuwait. The action prompted immediate international outrage. The United Nations demanded that Iraq withdraw. When it refused, the United States led an international coalition of thirty-eight countries—the largest military alliance since World War II—to liberate Kuwait. U.S. President George H.W. Bush worried that a lack of international response could encourage Iraqi President Saddam Hussein to invade Saudi Arabia. This outcome would see an unpredictable dictator have complete control over much of the world’s oil supply. President Bush also believed Iraq posed a risk to Israel’s security, given its threats to use chemical weapons against the Jewish country. Additionally, he acted to defend the principle of sovereignty—that no country’s territory could be taken by force. Ultimately, more than five hundred thousand American troops fought in the Gulf War, leading to a swift defeat of Iraqi forces in 1991. But after liberating Kuwait, coalition forces decided not to push into Iraq’s capital, Baghdad, to depose its dictator. It would be another decade before U.S. troops returned to undertake that mission.

Marcel Van Hoorn/AFP via Getty Images

In 1992, building on the past success of institutions such as the European Coal and Steel Community and the European Commission, twelve European countries signed the Maastricht Treaty. This treaty enabled the creation of an even more integrated Europe through an economic and political union known as the European Union (EU). The EU works to secure “four freedoms” for its members: free movement of people, goods, services, and money. In practical terms, because of the EU, a German citizen can commute to work in the Netherlands and goods can travel over country borders as if they were moving within one country. A train ride from Vienna to Paris requires no passport or currency exchange. Products developed in Estonia adhere to the same rules as ones developed in Spain. Although the EU is the world’s second-largest economy, debates still rage over the direction of European integration: some European leaders decry the EU’s overreach in their national affairs. Others lament the EU’s limited ability to hold members accountable on issues such as budget deficits and undemocratic domestic legislation.

United Nations

In the 1990s, countries across the globe took some of the first steps toward limiting climate change-causing greenhouse gas emissions. In 1992, countries signed the world’s first international climate agreement—the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)—and, five years later, countries vowed to enact further reforms with the Kyoto Protocol. Although most countries signed on to the UNFCCC and Kyoto Protocol, the agreements have made limited progress toward addressing climate change, with many parties ignoring or blowing past emissions targets. The most recent multilateral climate treaty—the Paris Agreement—faces similar challenges of noncompliance, as participation is voluntary. Although several international accords have sought to promote global coordination on climate change, emissions reductions are mostly dependent on each country’s own climate actions. Largely as a result, annual carbon dioxide emissions in 2019 were 51 percent higher than levels at the signing of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, and average global temperatures have continued to rise at an alarming rate.

Gary Hershorn/Reuters

Israelis and Palestinians directly negotiated peace for the first time in the 1990s after decades of war, occupation, and mutual mistrust. This started with the 1991 Madrid Conference. It continued with a set of agreements that emerged beginning in 1993, known as the Oslo Accords. These agreements outlined the initial terms of a process that could lead to a two-state solution; an outcome intended to provide lasting Israeli security in exchange for an independent Palestine living in peace with its Israeli neighbor. The accords established a Palestinian Authority in 40 percent of the West Bank and most of Gaza. The agreements did not, however, resolve some of the conflict’s toughest challenges—such as defining borders of a future Palestinian state, reconciling Israeli security with Palestinian sovereignty. Moreover, the Oslo Accords also failed to address the return of Palestinian refugees and decide who would control the holy city of Jerusalem. Nevertheless, these negotiations marked the closest Israelis and Palestinians have come yet to achieving peace in their decades-long conflict. Optimism over the deal was short-lived: In 1995, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by a Jewish extremist. In 2000, the Palestinians launched an uprising (the intifada) which dashed hopes for peace. In 2005, Israel withdrew unilaterally from Gaza, and the following year Hamas (an organization committed to the destruction of Israel) was elected to power there. Meanwhile, Israel has continued to occupy the West Bank and expand its settlements, as peace remains elusive.

Scott Peterson via Getty Images

In 1994, UN peacekeepers monitoring local elections in Rwanda stood on the sidelines as simmering ethnic tensions erupted into genocide. Just three months later, more than eight hundred thousand Rwandans were dead. The failure to stop this violence—in addition to further atrocities unfolding in the former Yugoslavia—led to UN members endorsing the responsibility to protect (R2P) doctrine in 2005. R2P states that countries have a responsibility to protect their citizens and, if they fail to do so, that responsibility falls instead on the rest of the world. In other words, countries can use all means necessary—including military intervention—to prevent large-scale loss of life. The R2P doctrine represented a potentially meaningful shift from previous decades in which unilateral humanitarian intervention was considered an unlawful violation of a country’s sovereignty. However, the doctrine would lose international consensus in 2011 after humanitarian intervention in Libya quickly evolved into a destabilizing regime-change operation.

Renaud Giroux/AFP via Getty Images

In 1994, the Americas became home to one of the most ambitious free trade agreements ever written. The United States, Canada, and Mexico signed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) to increase trade among the three countries. NAFTA was designed to increase the free flow of goods by removing or lowering trade barriers like tariffs and quotas. Indeed, after NAFTA was implemented, trade tripled among the United States, Canada, and Mexico. As a result, the U.S. economy added billions of dollars in growth each year. But as with globalization generally, NAFTA brought both benefits and costs to North American countries. Specifically, the elimination of some jobs in the region would prove to have negative externalities and unintended consequences. In the United States, anti-globalization concerns about manufacturing jobs moving overseas helped elect President Donald Trump. In his campaign for the White House, Trump promised to renegotiate NAFTA and get a better deal for American workers. In 2018, the three countries signed a revised trade deal called the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement. This updated agreement added new laws to NAFTA that addressed the internet and intellectual property and restructured agreements on dairy and manufacturing businesses.

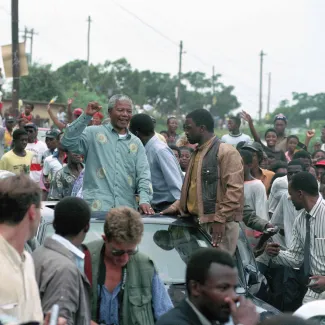

Per-Anders Pettersson/Getty Images

Afrikaners—South African descendants of Dutch settlers—systematized three hundred years of racial segregation after they came to power in white-only elections in 1948. During this period, they implemented a policy known as apartheid to prevent Black South Africans from voting, moving freely throughout the country, living in white neighborhoods, and working at certain jobs. After years of armed resistance and under global pressure to reform, the white South African government, led by President F. W. de Klerk, entered negotiations with the African National Congress (ANC)—a Black political organization—in order to avoid a civil war. The negotiations gave the majority Black South African population control over the government. In exchange for political concessions, white South Africans retained much of their wealth and control over the economy. In 1994, South Africa held its first free and fair elections. Nelson Mandela—the leader of the ANC who had spent twenty-seven years in jail for protesting apartheid—became the country’s first Black president. These days, reports of massive corruption by ANC leaders and persistent inequality within South Africa have eroded the party’s legitimacy. However, the ANC has remained in power—in large part due to its status as the group that ended apartheid.

Library of Congress

Today, the Panamanian government owns the Panama Canal, but this wasn’t always the case. In fact, a 1903 U.S.-Panamanian treaty guaranteed the United States the right to construct and run the canal in perpetuity. The opening of the canal in 1914 helped decrease shipping costs by 31 percent and propelled the United States—which could now sail far more easily between its own two shores—on its journey toward becoming a world power. However, many Panamanians had long challenged the validity of the U.S. treaty with Panama. By the 1960s, tensions had escalated over what Panamanian leader Omar Torrijos later described as the “foreign flag piercing [Panama’s] heart.” In 1977, President Jimmy Carter signed two treaties: one promising to transfer the canal back to Panama by the new millennium and the other protecting the U.S. right to intervene militarily if the canal’s neutrality came under threat. The U.S. Senate approved these agreements by a one-vote margin. Two decades later, Carter was on hand to mark the change in the canal’s ownership. On December 14, 1999, he told Panamanian President Mireya Moscoso, “It is yours.”

Peter Morgan/Reuters

On September 11, 2001, militants from the terrorist group al-Qaeda hijacked four planes and used them as weapons to kill 2,977 people in the United States. Those attacks would lead the United States to launch two generation-defining wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. U.S.-led coalition forces invaded Afghanistan in October 2001. The military operation was designed to retaliate against not only al-Qaeda but also the Taliban, which had protected the terrorist group. Although the coalition initially brought down the Taliban, the group has since regained control over much of the country. Now, two decades after the invasion, the United States has left the country without having secured lasting peace. Meanwhile, U.S.-led coalition forces invaded Iraq in 2003 on the basis that Saddam Hussein was hiding weapons of mass destruction. Coalition forces quickly defeated the Iraqi army, and Saddam was ultimately captured, put on trial, and executed. But the United States failed to find weapons of mass destruction and to plan for its subsequent occupation of Iraq. The U.S.-Invasion of Iraq resulted in massive civil unrest, the rise of insurgent militias and terrorist groups, and killed over one hundred thousand civilians.

Getty Images

Cyberattacks allow countries and individuals to disrupt or destroy computer systems, potentially causing catastrophic damage in real life. The United States and Israel reportedly conducted the first such attack when they sought to stymie Iran’s progress toward building a nuclear weapon. In 2007, Iranian engineers unwittingly connected virus-infected thumb drives into the computer networks running the country’s nuclear program. Ultimately, this Stuxnet computer virus destroyed one-fifth of Iran’s nuclear centrifuges when it covertly instructed the machines to spin dangerously out of control. To this day, Israel has continued to use cyberattacks to limit Iran’s nuclear capabilities.

Reuters

On December 17, 2010, a Tunisian street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in protest of his government’s endemic corruption and abuses of power. His self-immolation struck a chord with young people around Tunisia and the Middle East. Within days, protests spread across the region as millions demanded political, economic, and social reforms from chronically unresponsive governments. Such shows of civil disobedience had been extremely rare in countries where authoritarian leaders forbade political dissent. The protests (collectively referred to as the Arab Spring) took different trajectories. Tunisia successfully transitioned from authoritarianism to a fragile democracy. Egypt held its first democratic presidential elections in 2012, only to see a counterrevolution return the country to military rule one year later. Today—a decade after the first Arab Spring uprisings—most ruling power structures remain in place. Since Bouazizi’s self-immolation inflamed the region, few reforms have actually taken root, and countries such as Libya, Syria, and Yemen have descended into civil war.

Antonio Masiello/Getty Images

On September 7, 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced his signature foreign policy undertaking: a massive global investment plan known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Under BRI, Chinese institutions have loaned hundreds of billions of dollars to over 130 countries for projects such as new railways, roads, and bridges. As a result, China has become the world’s largest creditor—larger even than the United States and organizations like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Although BRI projects have the potential to raise global income by 3 percent, they have increased indebtedness in host countries to a worrying level. Some countries have even begun to question the economic feasibility of projects. Meanwhile, others criticize BRI projects’ disregard for human rights and their funding of nonrenewable energy sources like coal-fired power plants.

David W. Cerny/Reuters

In late 2019, doctors in Wuhan, China began noticing a spike in patients with pneumonia caused by a new kind of coronavirus. The Chinese government, however, quickly tried to downplay the seriousness of the situation. By delaying disease reporting, undercounting cases, and silencing whistleblowers, China prevented any chance of a coordinated global response to the impending crisis. During this time, the disease spread rapidly throughout the country and around the world. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization officially declared the COVID-19 health crisis a global pandemic, with infections reported in over a hundred countries. By the following March, nearly 130 million people globally tested positive for COVID-19, and upwards of 3 million people died from the disease. Beyond the cost of human life, the crisis caused unprecedented upheaval across health systems and economies. Not every country has experienced the crisis equally. For instance, the United States—home to just 4 percent of the world’s population—accounted for 18 percent of all COVID-19 deaths as of May 2021. On the other hand, the United States has also been a global leader in vaccine development and rollout. Government policy has led to the administration of vaccine doses to roughly half its population. As governments and international institutions race to react to COVID-19, the world has gotten a painful reminder of how—in today’s globally interconnected era—the problems of one country can ripple across borders and affect the entire world.