How Are International Agreements Helping Fight Global Warming?

Explore the challenges facing international cooperation and the major treaties where the world has agreed to work together.

Global warming is a global challenge. Greenhouse gas emissions from one country warm the planet for all countries, so stopping climate change requires countries to work together.

But over the years, finding ways to cooperate hasn’t been easy.

Climate change is perhaps the most serious collective-action problem humanity has faced since the dawn of the nuclear era.

A collective action problem arises when a group would be better off as a whole if its members joined forces, but at the same time, those members have reasons to act selfishly and not cooperate. With climate change, cooperation means countries using their limited resources to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, despite each individual country’s temptation to use those resources for other national priorities instead.

Even if every member of the group recognizes that working together is the better path, they could worry about free riders. Free riders are countries that don't cooperate (lower emissions) but still gain the benefits of other countries’ efforts (less climate change). If cooperating countries fear being taken advantage of by free riders, they could be wary of joining the group effort at all.

International agreements can address those concerns. If every country responsible for significant greenhouse gas emissions agrees to take certain actions—and agrees to measures that discourage free riding—then cooperation can be successfully achieved.

Of course, some recurring questions make it harder to reach international agreements on climate change. Here are two big ones:

Should some countries reduce more of their emissions faster than others?

The United States and Europe together account for nearly 40 percent [PDF] of global emissions since the late nineteenth century. The coal, oil, and natural gas burned over the course of the twentieth century helped make those countries some of the richest in the world. But nowadays, East Asia (mainly China) emits nearly 30 percent of the world’s greenhouse gasses each year. That’s more than double North America’s annual emissions and triple Europe’s. The historical and continuing accumulation of emissions in the atmosphere has begun to cause extreme weather across the globe, ranging from deeper droughts, bigger wildfires, extended heatwaves, and more intense storms. It has also caused accelerating sea-level rise. The damage can be severe even in countries that have emitted relatively little greenhouse gas.

Stopping climate change will require emissions reductions in both regions. But is it unfair for rich Western countries to demand that developing countries not follow their footsteps to economic growth? Or is mitigating climate change as fast as possible more important than addressing inequality? If both are essential, do wealthy countries owe money to developing countries to help them develop more sustainably? Many leaders disagree on the answers to those questions—making it difficult to determine what role each country should take in tackling climate change.

Who should pay for the climate damage already done?

Poor countries, like small islands in the Pacific that could disappear as seas rise, are experiencing harm from how the earth’s climate is currently changing and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Should the countries that emitted the historical greenhouse gases that caused most of today’s existing warming compensate the victims? What about in the future, when the effects could be even larger?

Reaching agreement

Despite those questions and hurdles, the world has made some progress on coordination.

The United Nations, established after World War II in part to resolve the world’s collective challenges, has been an important forum for national governments to try to forge consensus and cooperation. Over the last four decades, countries have, through UN-based negotiations, agreed to take important steps to fight climate change.

Here are some of the most noteworthy agreements.

September 16, 1987: Montreal Protocol

In the 1980s, scientists were concerned that certain chemicals were destroying the ozone layer in the earth’s atmosphere. The layer helps protect the earth’s surface from dangerous ultraviolet radiation. Without it, human beings would suffer far more skin cancer and other terrible effects (including more global warming). In 1987, world leaders gathered in Canada and negotiated the Montreal Protocol, a binding agreement that requires signatories to restrict the production and consumption of nearly one hundred man-made, ozone-depleting substances, such as chlorofluorocarbons. Countries were required to make specific, measurable reductions in their dependence on those chemicals and to report their progress to a central body. Developing countries were given extra time to cut their usage because the transition would be more economically burdensome for those poorer countries—and because their low levels of use caused less harm to the atmosphere.

Within decades, the Montreal Protocol enabled a dramatic rebound in the health of the planet’s ozone layer. Scientists project that the layer will be fully restored by the middle of the twenty-first century. Although the protocol was not intended to tackle climate change, it was considered a successful model for other international environmental agreements.

June 14, 1992: UN Framework Convention on Climate Change

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) established the United Nations’ forum for climate change negotiations. Its main objective is to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere, which it pursues through an annual multilateral meeting known as the Conference of the Parties (COP). During COP meetings, which occur every year, countries review their goals and progress on climate agreements.

The UNFCCC also established the principle of “Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities” (CBDR-RC). It’s a long title, but it addresses the first question above: Should some countries do more than others? Under CBDR-RC, the answer is yes. Richer countries, says the agreement, should do more. That notion remains one of the more controversial parts of any international climate agreement.

December 11, 1997: Kyoto Protocol

The Kyoto Protocol was signed at one of the earliest COP meetings. It committed industrialized countries to reducing and capping greenhouse gas emissions by specific degrees. However, it did not place similar requirements on large developing countries like India and China. That discrepancy made the agreement politically controversial in the United States. President Bill Clinton signed the protocol in 1998, but the Senate never ratified it during his term. Then, the next president, George W. Bush, made it clear he opposed moving forward with the protocol. Other countries did ratify it and the protocol went into force, though its effect on global emissions has been limited.

For one, the protocol was supposed to be legally binding. But after the United States pulled out, some other countries followed, all without penalty. Second, while industrial countries did reach Kyoto Protocol targets, global emissions still rose due to the activities of countries excluded from the agreement. However, the protocol helped policymakers shape the approach for future agreements.

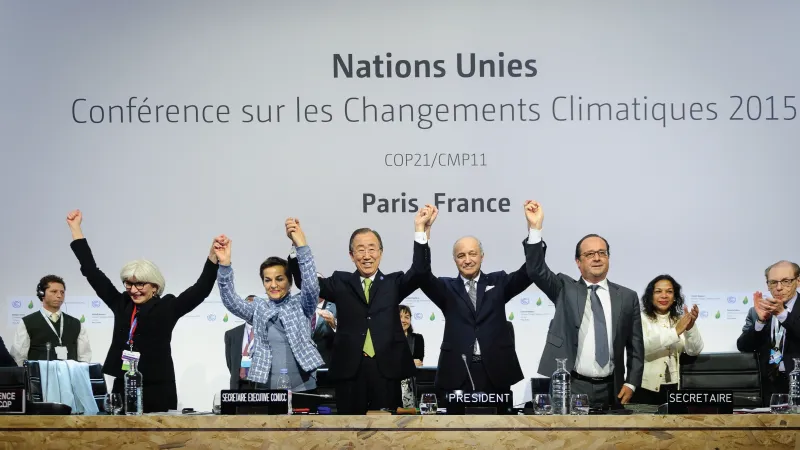

December 12, 2015: Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement, signed at the twenty-first COP, was the first to require all signatories to participate in emissions-reduction efforts. To achieve universal participation, it does not require countries to make specific cuts. Rather, it invites them to publish their own plans for voluntary emissions reductions. Those are known as nationally determined contributions, which are reviewed and ideally strengthened every five years.

Importantly, the agreement also set a goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C above preindustrial times.

Although not perfect, the Paris Agreement was a monumental moment for international cooperation on climate change. The agreement also broached the second question from above: Who should pay for climate change’s effects? The agreement recognizes the need to address “loss and damage” from climate change. And though it calls on rich countries to share resources and “enhance understanding, action and support,” it doesn’t allow affected countries to claim compensation for the current harms from historical emissions.

Do the agreements really work?

Because they reflect some degree of global consensus, those documents carry immense legitimacy and respect. Some, like the Montreal Protocol, have even achieved many of their goals. However, they do not always wield equal power, as not every individual country ratifies each international agreement into law. If the agreements aren’t ratified, they aren’t legally binding.

But even if the agreements are ratified, countries can have difficulty coordinating a punishment for other countries that break their binding commitments. For example, other countries couldn’t do much when the United States under President Donald Trump withdrew from the Paris Agreement in 2020 and refused to pay the billions of dollars in support it had promised. (The United States rejoined in early 2021 under President Joe Biden.)

Nevertheless, many countries have strengthened their climate commitments since signing the Paris Agreement. Before the agreement, the world was on track for 4°C of warming by the end of the century. Now, with current policies, the world is on track for around 2.7°C of warming.

Experts agree those emissions still aren’t declining fast enough. According to the scientific project Climate Action Tracker, no country’s policies and commitments are compatible with limiting global warming to the 1.5°C Paris Agreement target, and some of the largest emitters’ efforts are highly insufficient.

At minimum, those agreements and protocols are public commitments made by national governments—to which other countries, nongovernmental organizations, and regular voters can theoretically hold them accountable.