The Greenhouse Effect

How do greenhouse gas emissions contribute to global warming? Learn why the world is getting warmer in this free climate change resource.

The world is getting hotter. Heat waves are more intense. Ice caps are melting faster. Wildfires rage across landscapes once known for their cooler climates. But what’s driving that relentless rise in temperatures? The answer lies in a process that has shifted from a natural balance to an alarming trend—the greenhouse effect.

How does the greenhouse effect work?

The greenhouse effect is named after actual greenhouses—buildings designed to provide a warm, supportive environment for plants to grow during colder months. Greenhouses are generally made of clear materials that allow sunlight to enter. The sunlight warms the air inside while providing a barrier that stops the heat from leaving. That ensures the temperature inside remains hospitable.

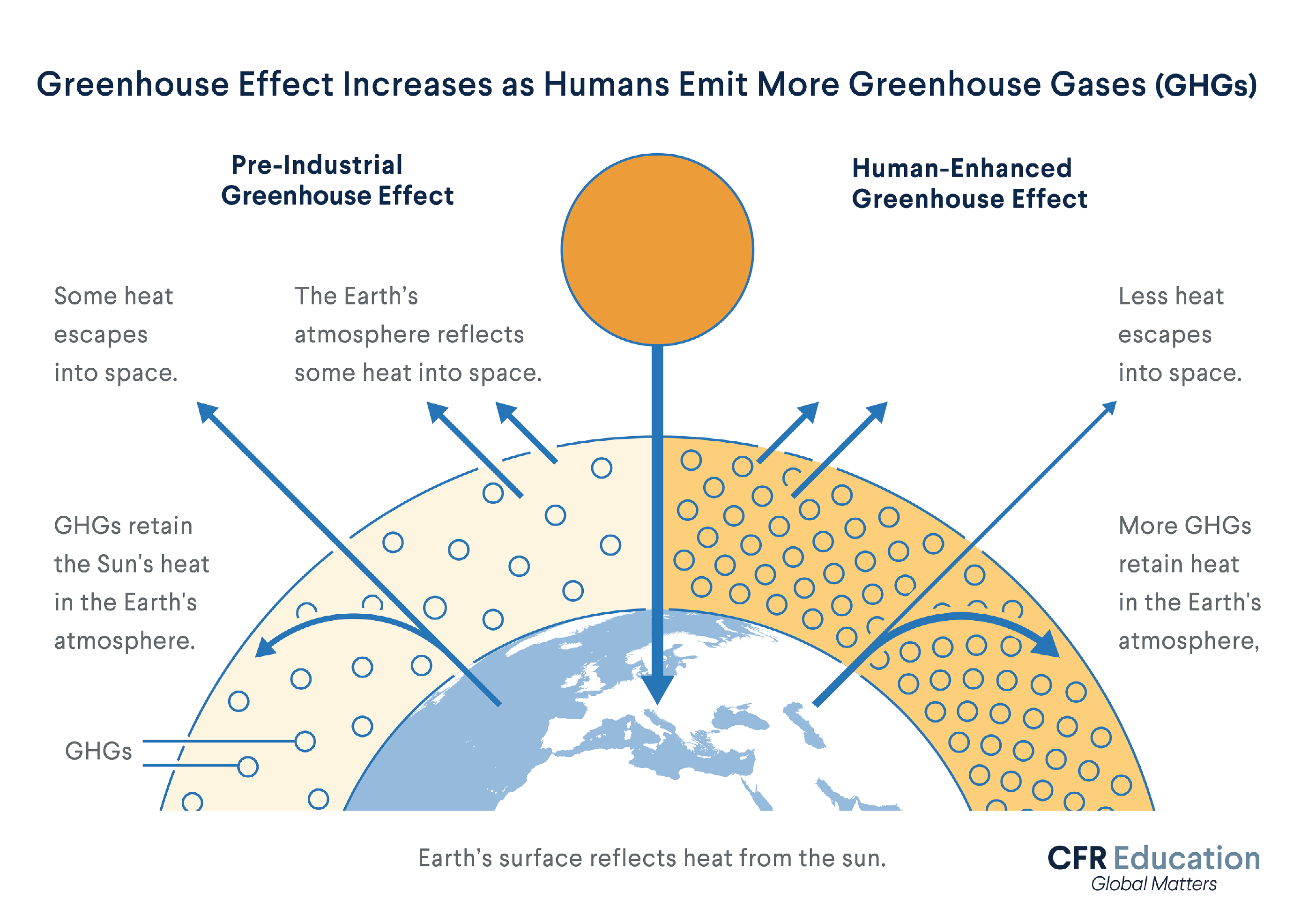

The earth’s atmosphere functions in a similar way. Most of it (99.5 percent) is made of nitrogen, oxygen, and argon. The sun’s energy passes through those gases, bounces off the earth’s surface, and goes back into space.

Greenhouse gases—such as carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxides, and water vapor—are different. When the sun’s energy reflects off the earth’s surface, it is converted into heat, which those gases absorb and keep in the atmosphere. Greenhouse gases, despite accounting for just a tiny percentage of the atmosphere, are the reason the planet is warm enough for humans to live on. Without those gases, Earth’s average temperature would be -4°F (-20°C), compared to the 57°F (14°C) average temperature the planet has had since the 1880s.

So what's the problem?

The problem isn’t the greenhouse effect itself, but rather that humans are increasing the number of gases that drive the effect, making the atmosphere hotter than it has been in the past.

Geological records show that for hundreds of thousands of years, the amount of carbon dioxide (the most plentiful greenhouse gas) in the atmosphere fluctuated between 180 to 280 parts per million (ppm). But that all started to change in the mid-eighteenth century with the Industrial Revolution. Humans started releasing more and more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, mainly by burning fossil fuels. Since then, carbon dioxide has grown to account for more than 400 ppm in the atmosphere—nearly 150 percent of its historical maximum. Additionally, concentrations of methane have more than doubled, and other greenhouse gases have increased as well.

Those powerful gases still make up a relatively small percentage of the atmosphere. However, their large percentage increases lead to the atmosphere trapping more of the sun’s energy. Since 1880, the earth’s average temperature has increased by about 1.9° F (1.1°C).

Now, a two-degree temperature change could seem slight. But it can lead to some pretty harmful consequences:

- more frequent and intense extreme weather

- sea level rise

- food and water scarcity

- stress on human health and increase in disease

- economic damage

- national security threats

- migration crises

- worsened social inequalities

All of those harmful consequences are happening right now—but they could get worse. Scientists warn that human activity will likely raise global temperatures to 2.7˚F (1.5˚C) above nineteenth-century averages by 2050. Without a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, global temperature could even rise 3.6˚F (2˚C), which could lead to catastrophic consequences: for example, nearly all coral reefs could die out, and sixty million more people could experience severe drought.

Humans can limit such damage by reducing their greenhouse gas emissions through what’s referred to as mitigation.

It’s important for the world to act sooner rather than later. The earth’s natural processes are complex, and a little bit of warming can trigger dangerous feedback loops that accelerate climate change. And once we pass certain thresholds of warming, the risks could be catastrophic.