Understanding Intrastate Conflict

Conflicts between countries have been some of the deadliest affairs in human history. An estimated sixty million people—3 percent of the world’s population—died during World War II.

Since 1945, when World War II ended, interstate wars have become increasingly rare. However, conflicts within countries are now much more common. When conflict breaks out inside a country, this is known as intrastate conflict. Many of the deadliest conflicts of the twenty-first century have occurred within the borders of a single country.

In today’s interconnected world, challenges within one country’s borders have ramifications for the entire globe. Terrorists can capitalize on conflict-induced instability to plot attacks at home and in faraway cities. Infectious disease outbreaks in conflict zones can easily spread uncontrolled across borders. Millions of refugees fleeing violence can increase pressure on neighboring countries’ public services.

This resource explores the types, causes, and consequences of intrastate conflict and dives into the policies countries can implement to address those issues.

What is intrastate conflict and civil war?

Civil war is the clearest case of intrastate conflict, and it generally takes two forms.

Wars of secession occur when people fight to form an independent country. One example is the American Civil War, in which southern, slaveholding states attempted to break away from the United States and form a new country—the Confederate States of America. The South’s secession was motivated primarily to protect the institution of slavery.

Wars of succession, in which people fight to overthrow ruling authorities, are the second type of civil war. The Arab uprisings in Libya, Syria, and Yemen—during which anti-government protesters fought to oust oppressive political leaders—devolved into prolonged and violent wars of succession.

However, civil wars are just one type of intrastate conflict. Groups fight for many reasons besides seeking independence or a new government. Criminal organizations like drug cartels and terrorist groups like the self-proclaimed Islamic State incite violence to control territory and people. Governments persecute minority groups to crush dissent or preserve social hierarchies; the United Nations accuses the Myanmar government of committing acts of genocide against a Muslim ethnic minority known as the Rohingya. Fighting erupts between citizens and governments over economic issues including corruption and lack of opportunity. Intrastate conflict can also occur due to competing claims to territory and natural resources.

Weak, failing, or failed states—in which the government is unable to perform central functions like maintaining security or providing basic services such as electricity, health care, and education—are particularly vulnerable to conflict. In those countries, governments are often unable or unwilling to control what happens inside their borders. Such a situation can allow terrorists and criminal groups to operate freely.

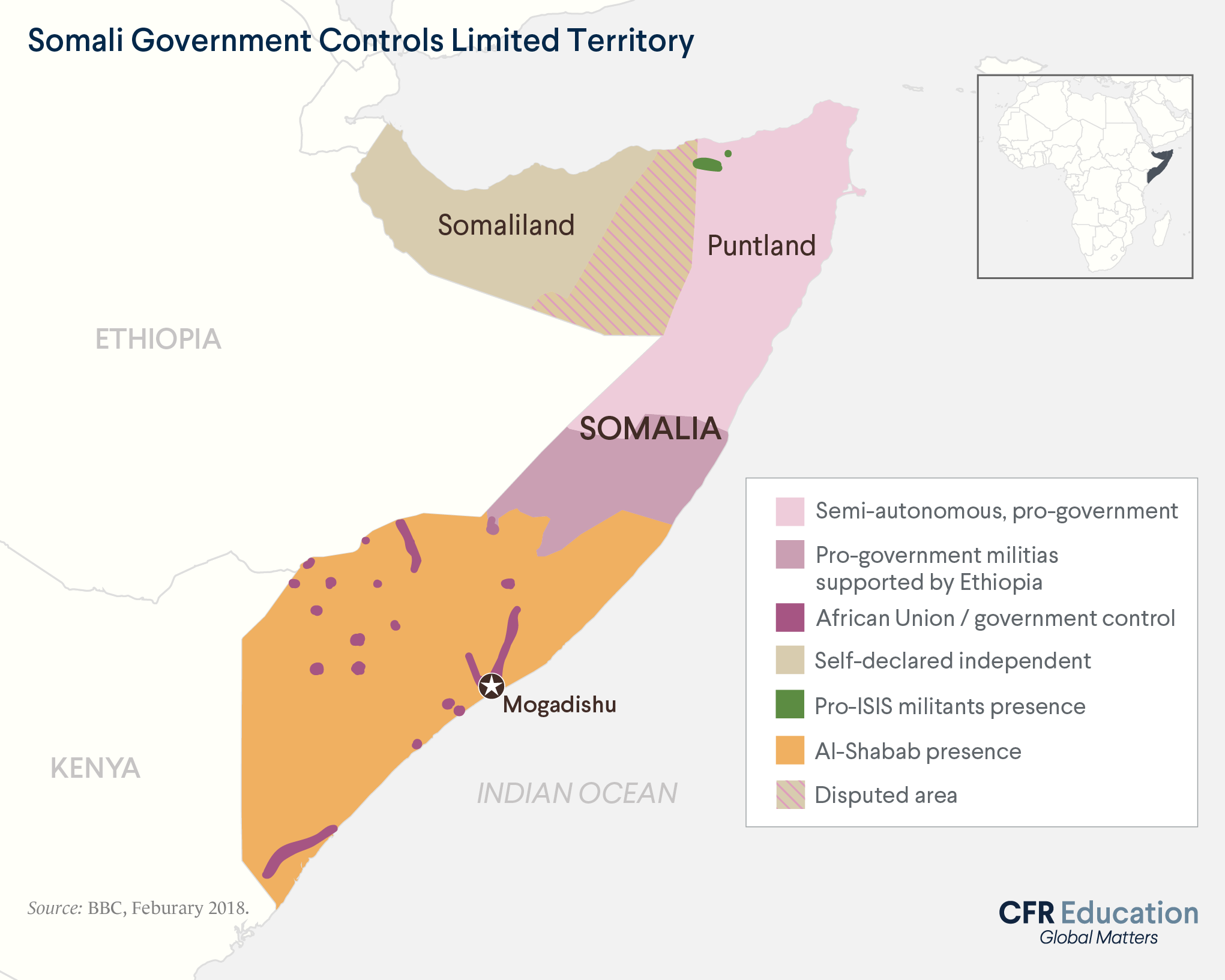

Intrastate conflict can also produce state failure by weakening a government’s control over its territory, as is the case in Somalia. Attacks by al-Shabaab, a terrorist group, have left Somalia’s already fragile government unable to carry out crucial functions. The Somali government has failed to maintain security and respond to natural disasters like a devastating drought in 2011. More than two million Somalis are internally displaced and face severe levels of hunger.

Types of Intrastate Conflict

Civil War

War of Secession

Definition: Conflicts involving groups of people united by common beliefs, aims, or territory that fight to establish an independent country.

Example: In the American Civil War, southern slaveholding states attempted to break away from the United States and form a new country—the Confederate States of America—where slavery would remain legal.

War of Succession

Definition: Conflicts involving groups of people seeking to overthrow and replace a country’s government or ruling authority.

Example: In 2011, anti-government protesters in Libya overthrew the country’s longtime dictator, Muammar al-Qaddafi. However, nine years after al-Qaddafi’s ousting, rebel groups have yet to form a unified government. As a result, conflict in Libya persists.

Violence Waged by Terrorist or Criminal Organizations

Definition: Conflicts involving terrorist or criminal organizations that commit acts of violence for political, ideological, or financial reasons.

Example: In Mexico, cartels use violence to exert control over the country’s politics and dominate its illegal drug market. In 2018, drug-related violence resulted in more than 33,000 homicides. These homicides include the deaths of at least 130 candidates and politicians.

State-Sanctioned Violence

Definition: Conflicts involving the police, military, or other government groups persecuting the country’s own citizens—often targeting those from a minority group.

Example: For decades, Buddhist-majority Myanmar has persecuted religious minorities in the country, including its Rohingya Muslims. That persecution escalated in 2016 with a brutal crackdown by the country's military. The United Nations later labeled the assault a genocide.

Resource-Driven Conflict

Definition: Conflicts involving several groups vying to control and profit from a country’s natural resources.

Example: South Sudan’s lucrative oil reserves drive conflict. The government-controlled oil sector makes up a major portion of South Sudan’s gross domestic product. However, most of the country does not benefit from the oil industry’s profits. Citizens have protested the oil companies’ appropriation of oil revenues, urging transparency and accountability; in response, the government has increasingly militarized oil production zones.

What are the global effects of civil war and other forms of intrastate conflict?

Although the most severe consequences of intrastate conflict are experienced where fighting takes place, some effects are far reaching.

Terrorists can capitalize on the instability caused by intrastate conflict to train, prepare for, and carry out attacks. In 2022, over 98 percent of all terrorism-related deaths occurred in countries that were embroiled in conflict or had high levels of political terror (which includes extrajudicial killings, torture, and imprisonment without trial). And though terrorism most often takes place in conflict-affected areas, terrorist groups can launch attacks in neighboring countries and faraway cities.

Additionally, intrastate conflict can weaken a country’s health system, impairing its ability to contain infectious disease outbreaks. Liberia and Sierra Leone struggled to control a 2014–16 Ebola outbreak in part due to poor health infrastructure. The lack of accessible health-care in those countries was precipitated by conflicts from the prior decade. Public mistrust of health officials, after decades of unequal health-care access, further made it possible for Ebola to spread quickly across borders in West Africa. Ultimately, the Ebola outbreak killed more than eleven thousand people.

Meanwhile, conflicts in Afghanistan, Syria, Venezuela, Yemen, and elsewhere have forced at least one hundred million people to flee their homes over the past decade. That mass displacement has led to refugees experiencing high rates of hunger, poverty, and sexual violence. Additionally, neighboring countries have faced challenges of suddenly accommodating thousands—if not millions—of new residents. Lebanon’s population increased by 25 percent after receiving Syrian refugees fleeing the civil war. The Lebanese government even split its school days into two shifts to accommodate the new students. However, more than 30 percent of Syrian refugee children remained unenrolled in 2022.

How can countries prevent and stop civil war and other forms of intrastate conflict?

Countries have various tools for responding to intrastate conflicts.

Elections: Governments can become more inclusive through free and fair elections. Governments can also institute reforms to address underlying drivers of conflict. Countries can also pursue diplomacy or offer economic incentives to opposition groups.

Negotiations: Outside mediation can also prove productive when parties to an intrastate conflict have been unable to compromise. For example, foreign countries can try to bring the warring groups to diplomatic talks. Such was the case in Northern Ireland in the 1990s after three decades of fighting between the region’s pro-British Protestants and pro-Irish Catholics. With the support of the British and Irish governments—and mediation by U.S. Senator George Mitchell—Northern Ireland’s opposing parties signed a peace deal called the Good Friday Agreement. Afterward, violence largely ended.

Sanctions: Foreign countries can also use sanctions to incentivize one or both parties in intrastate conflicts to come to the negotiating table. Sanctions can also be utilized to apply pressure on countries to implement reforms. That situation occurred in 1986 when the U.S. Congress passed the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act, which imposed economic sanctions on South Africa for its violent discrimination against Black South Africans.

Military Intervention: Additionally, foreign countries can intervene militarily to prevent further violence. The United Nations can build and deploy its own multinational military force consisting of personnel, called peacekeepers, supplied by member countries. The United Nations has sent peacekeepers to conflict zones to protect vulnerable people, enforce cease-fires, and safeguard elections, among other missions. In 2023, more than eighty thousand peacekeepers were active in twelve countries, constituting one of the largest military forces deployed abroad.

Military intervention can alleviate some of the harm intrastate conflict causes. However, they are not always enough to create peace. And in certain instances, outside interference—especially military intervention—can even exacerbate fighting. This undesirable outcome occurred after the North Atlantic Treaty Organization intervened in Libya in 2011.

Ultimately, countries have a limited ability to respond to intrastate conflicts elsewhere because of sovereignty. This principle, that countries have the authority to control what happens within their borders, constrains the nature of the international community’s response to intrastate conflict. However, some experts argue that a rethink of traditional understandings of sovereignty is required in an era in which one country’s domestic issues can trigger global consequences. According to that line of thinking, when countries fail to protect their citizens or do not meet their obligations to other countries to control infectious disease or prevent terrorism, those countries forfeit their right to sovereignty. Under such conditions, they argue, foreign countries can and should intervene.