Global Health Then and Now

The world has become healthier over the past few centuries, but new challenges are on the horizon.

Health has played a critical role in shaping the world’s economies and societies throughout human history. As civilizations have advanced and globalized, new challenges in human disease, nutrition, sanitation, and public health financing have emerged. So, too, have advances and innovations that have helped human beings live longer and healthier lives than ever before.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 was just one example of how a health crisis can go global.

As communities look forward to the future and the new challenges that could emerge, they should take stock of just how far the world’s health-care systems have come in two centuries.

In 1800, for example, the estimated global life expectancy was just twenty-nine years. Today, global life expectancy is approximately seventy-two years. That means that in just two short centuries, the average length of people's lives has more than doubled, thanks to great strides in areas such as medical research, sanitation, and vaccines.

Those gains reflect the world’s increased commitment to improving global health. Over the past century, new organizations and funding to advance human wellness have steadily grown. Hundreds of different governmental and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), international organizations, governments, funds, and initiatives now work on health issues, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Doctors Without Borders, and the World Health Organization. Gavi, a vaccines-focused public-private partnership, has helped vaccinate over 1 billion children since it was founded in 2000.

Thanks in part to many of those organizations, certain infectious diseases no longer pose major threats.

For thousands of years, smallpox ravaged parts of the globe, killing about one-third of those who caught it. But better science led to a new vaccine, which, combined with funding and political will, resulted in its official eradication of the disease in 1980. A disease that killed an estimated three hundred million in the twentieth century alone now no longer endangers societies.

Polio has almost been eradicated too. Just over three decades ago, the disease was common in 125 countries. Today, it’s geographically prevalent in—or endemic to—just two: Afghanistan and Pakistan. Polio persists in those settings largely because delivering vaccines there is difficult, either for geographic reasons—many people live in rural areas or move around frequently—or for political reasons, such as local mistrust of Western NGOs.

Despite a century of progress, however, infectious diseases remain a threat. And global health gains haven’t been uniform.

Medical experts have made progress worldwide in preventing and treating HIV/AIDS. In 2022, global deaths from the virus had decreased by 69 percent since its peak in 2004. New HIV infections have also fallen: by the end of 2022, about thirty million people with HIV were accessing antiretroviral therapy—up significantly from just eight million in 2010. But nearly forty million people still live with HIV/AIDS, the majority of them in Africa, despite a large coordinated effort to counter the epidemic.

Nor are those gains permanent.

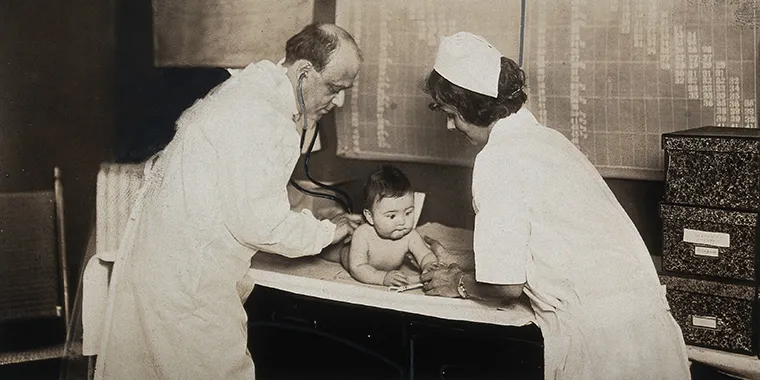

Maternal and infant deaths have declined extraordinarily since 2000, when the United Nations announced a set of priorities, the Millennium Development Goals, that included children's and mothers' health. Since then, governments, NGOs, and private partners have invested in more programs—such as sex education, nutrition, and pre- and postnatal care—that help mothers and babies stay healthy. More families also have access to better clinics and trained health professionals.

Despite the decline in global maternal mortality rates in the twenty-first century, since 2016, rates in the Americas and Europe have either increased or stagnated.

Maternal mortality has risen and seen a recent spike in the United States—the only high-income country where that increase is occurring. Those climbing numbers are particularly concerning in how they relate to U.S. racial disparities: in 2021, the country’s Black maternal mortality rate was nearly three times higher than its white maternal mortality rate.

While a century of progress can’t be discounted, the world continues to face health challenges.

Meanwhile, the world is combating the rise of other health threats called noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). NCDs do not spread from person to person. Heart disease, for example, is now the biggest killer in the United States—it causes one in every five deaths. That statistic mirrors a global trend. In 2000, just four of the top ten causes of death worldwide were NCDs; by 2019, that number had grown to seven out of ten. Worldwide, nearly three-quarters of all deaths now result from NCDs—the majority from cardiovascular diseases.

In the United States, those illnesses disproportionately affect people of color. For instance, Black and Hispanic/Latino Americans face higher rates than white Americans of high blood pressure, obesity, and diabetes—dangerous conditions that can also make COVID-19 even more threatening. About 90 percent of Americans hospitalized with coronavirus in March 2020 had one of those or similar preexisting conditions.

The questions surrounding how best to treat NCDs and how to tackle other emerging health challenges emblemize a shift in the global health field: the idea that health is about more than just doctor visits and vaccinations. In fact, a range of issues—including poverty, gender equality, systemic racism, and climate change—affect a person’s health and their vulnerability to NCDs. Advances in those related areas mean progress in global health too.