What Is Intelligence?

From Cold War double agents to Chinese spy balloons, explore how lying and spying inform policymaking in this resource on intelligence.

Have you ever played I Spy? Usually, the game involves scanning a cluttered image to find specific objects such as a toy car, a shovel, or a bowling pin.

But at one point in U.S. history, officials used that method to gather critical intelligence. Some experts believe that such information helped the world avert nuclear disaster.

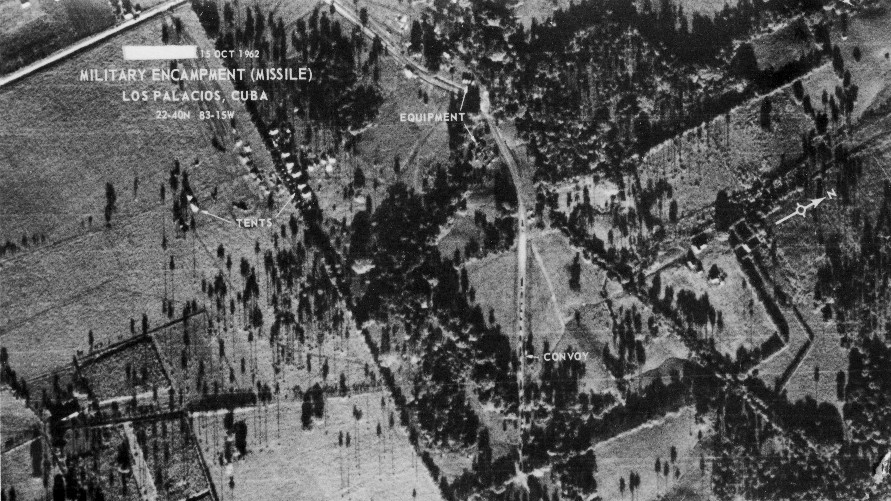

On October 14, 1962, amid escalating U.S.-Soviet Cold War tensions, an American spy plane snapped photos over communist Cuba. The intelligence revealed irregular objects in an area of ranchland.

Photo research experts analyzed the pictures and realized they were looking at Soviet missiles. That finding revealed the threat of nuclear weapons less than one hundred miles from U.S. soil. For thirteen days, the United States lived under agonizing tension in what came to be known as the Cuban Missile Crisis.

U.S. President John F. Kennedy and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev eventually reached a compromise: the Soviets withdrew their missiles from Cuba in exchange for the United States secretly doing the same in Turkey and Italy. The United States also publicly promised not to invade Cuba. Through that deal, the two countries narrowly avoided war. But as one historian tells it, if the United States had found out about Cuba’s missile bases after they were operational, Kennedy likely would have responded with air strikes. This decision could have sparked nuclear war. In that view, the spy plane surveillance photos saved millions of lives.

In this resource, we’ll explore the different forms of intelligence, the reasons why countries spy, and the benefits and fallout from all those secrets and lies.

What is intelligence, and how is it gathered?

Intelligence is both a product and a process, acquired through espionage (spying) and practiced through covert action. Its goal is to provide governments with an unbiased view of what is happening in the world. Intelligence enables policymakers to make better-informed decisions—and to keep people safe from threats.

Spying, Espionage, and Intelligence Gathering

By definition, intelligence gathering in most of its forms has to remain secret. That’s because countries typically have laws against being spied on—making the practice inherently illegal. In addition, the information gained through spying needs to be kept classified so that foreign rivals don’t learn how much the spies know.

The intelligence cycle consists of five stages:

- Planning: The intelligence cycle starts with policymakers, who ask intelligence operatives to get to the bottom of specific issues on their behalf.

- Collection: Intelligence operations come in many forms, including infiltrating a military base or photographing it from outer space. Collection processes can include going undercover in an extremist group, intercepting an email, measuring the signals from a radar, emptying a wastepaper basket at the exact right moment—or simply scanning the news for publicly available information.

- Processing: Say spies are tracking a suspect over a month-long stakeout. In that time, they’ll gather an immense amount of information about that person’s life; with modern digital communications, that amount expands exponentially. Processing intelligence involves narrowing down all that information and putting it in a digestible format.

- Analysis: This stage involves figuring out what the collected information means and putting it all in context to create a final product. It is often compared to putting together a jigsaw puzzle—only, you don’t know the full picture in advance.

- Dissemination: Finally, intelligence agencies get the final product to the customer—often policymakers—to inform their decision-making. In the United States, the largest consumer of intelligence is the military. Figuring out how to present the information in a timely way and relevant is critical to success.

In addition to gathering information, intelligence operatives play defense through counterintelligence. This process involves opposing the work of foreign spies and protecting a country’s secrets.

In the United States, a whopping eighteen organizations make up the intelligence community (IC). Several of those organizations fall under the Department of Defense, including the IC’s newest member: Space Force Intelligence. Others are part of offices such as the Department of Homeland Security or the Department of State. But two agencies—the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and the CIA—are independent and report directly to the president.

At an international level, some countries collaborate to share intelligence. Following the Second World War, five countries—the United States, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom—formed an intelligence alliance called the Five Eyes that continues to this day.

Meanwhile, other countries are notorious intelligence rivals.

What are examples of espionage and spying?

Throughout the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union worked to recruit double agents. These agents work behind enemy lines and smuggle secrets from under the nose of their opponent. Today, the United States, China, France, India, Israel, Pakistan, Russia, and the United Kingdom all have widely respected intelligence services.

New debates have surged over spying in 2023 when a Chinese spy balloon was shot down by U.S. officials while flying over the United States. U.S. lawmakers have also accused Chinese company, Byte Dance, which owns the popular social media app TikTok, of intelligence harvesting. Byte Dance allegedly offers tools for Chinese officials to use U.S. citizens’ personal information for their intelligence purposes. Russia has also accused U.S. citizens of spying. U.S. government officials refute this—as in the controversial case of U.S. citizen Paul Whelan's imprisonment in Russia.

But countries don’t just spy on rivals. In 1984, for instance, Israeli operatives trained an American Navy intelligence analyst, Jonathan Pollard, on ways to collect and share U.S. intelligence with Israel. They did this despite the fact that the two countries were, and remain, close partners. Moreover, in 2015, WikiLeaks revealed that the United States had been tapping German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s phone calls for decades, despite Germany’s alliance with the United States.

The reality is that all countries spy; however, some countries are better equipped for the practice than others. One expert said the United States, for instance, has the equivalent of a “nuclear weapon” in its intelligence armory compared to most other countries, which are stuck with the equivalent of cannons.

Covert Action

The bulk of the intelligence community’s work serves to inform policymakers. However, a small portion involves trying to change the world through activities known as covert action.

The U.S. government defines covert action as activities aimed at influencing political, economic, or military conditions abroad, all while concealing the U.S. role. In the United States, such actions are only pursued at the direction of the president.

Covert action hinges on the principle of plausible deniability, which enables governments to deny involvement in specific measures. When it comes to covert action, leaders can see it as an attractive foreign policy tool. Covert action circumvents the high costs of war and other criticism associated with controversial public actions.

The CIA has long served as the primary agency behind U.S. covert action. Those activities have included assassination attempts, efforts to spark coups, cyberattacks, and drone strikes. Experts organize covert action into several categories:

- Lethal action: Perhaps the most notorious genre of covert action includes assassination and lethal force. Sometimes those actions take place within the context of conflict, while other times they involve a political motive. For example, governments use covert action to go after foreign leaders or other important figures they believe threaten their interests. Since 1976, the U.S intelligence community has been banned from using assassination as a foreign policy tool.

- Paramilitary action: Covert action can also involve arming and training surrogate forces abroad to carry out foreign policy objectives.

- Political or economic action: Not all covert action involves force. Some forms entail economic or political interference. This form of covert action, includes eradicating crops, tampering with elections, or channeling funds to rival political groups.

- Propaganda: Covert action also involves using information to manipulate people and advance a particular cause. For instance, governments can utilize the media to turn public opinion against an issue or leader.

Many countries use covert action to achieve foreign policy goals. For example, after the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the CIA helped drive the occupying force out of the country by arming and funding anti-communist Muslim insurgency groups collectively known as the mujahideen. (However, that same case shows how complicated the covert action's consequences can be. Many of those insurgents would go on to enforce a radical vision of Islam across the country and eventually fight U.S. forces years later.) More recently, in 2011, the United States sent a team of Navy SEALs on a covert raid in Abbottabad, Pakistan. This instance of violent covert action resulted in the killing of al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden.

The downsides of covert action can be significant. Assassination attempts can lead to retaliatory attacks, and coups can usher in repressive regimes. Where the United States has succeeded in overthrowing governments, research by some political scientists indicates countries have become less democratic. Moreover, these nations are more prone to civil conflict and mass killing.

Observers often claim that successful intelligence operations remain secret, while those that go awry become public knowledge. That argument suggests the world hears far more about instances when spies and other operatives get it wrong than when they get it right. That was certainly the case after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, when the IC missed opportunities to pool and analyze information across agencies leading up to the attacks. Intelligence failures also clouded the decision to invade Iraq. In 2005, a government report found the IC was “dead wrong in almost all of its pre-war judgments about Iraq's weapons of mass destruction.”

That said, headline-making failures sometimes overshadow intelligence wins that have shaped history. For example, a successful code-breaking operation by Allied forces in World War II likely shortened the conflict by several years. According to then U.K. Prime Minister Winston Churchill, this intelligence success ultimately “won the war.”

The future of intelligence

Around 2010, the Stuxnet computer worm—allegedly cooked up and deployed by the United States and Israel—destroyed Iranian nuclear centrifuges. Stuxnet became the first cyberattack to cause physical damage in the real world. That virus represents just one tool in the technological race advancing spycraft into a new, modern era.

Think about it this way—during the Cold War, if the United States sent you abroad as a spy, you could likely pass for a student with just a forged passport and other falsified documents. Today, though? You’d probably have some trouble scrubbing your existence from the internet. Governments with facial recognition technology could identify you by your old Facebook photos in no time. Plus, intelligence gathering is tougher with one billion surveillance cameras around the world tracking your movements.

As technology evolves, spycraft will adapt and change, leading to new developments and challenges in espionage and covert action. For example, those surveillance cameras that make it harder to hide abroad can also provide foreign intelligence agencies electronic access to lots of useful information about what is happening in that country. The rise of artificial intelligence, technology like ChatGPT, has also changed the landscape of spycraft.

What won’t change is intelligence’s role as a critical tool in policymaking. Leaders will always need to know what other countries—enemies and allies alike—are up to. The stronger a country’s intelligence capability, the more confident leaders can be that they understand the threats and opportunities facing their nation.

Now that this resource has covered the fundamentals of intelligence, put those principles into practice with CFR Education's companion mini simulation, Intelligence: Covert Action.