What Is Economic Statecraft?

Learn why China lends billions of dollars abroad each year through its Belt and Road Initiative and the implications of that free resource for recipient countries.

The Roman Empire of the first century had a serious problem—silk. The rich nobles of Rome were buying so much of the expensive Chinese import that politicians began to worry about the outflow of gold from the capital’s coffers. Outraged by the extreme spending, the Roman senate banned the fiber in 14 CE.

Rome is hardly the only society to have purchased its fair share of silk. In fact, global demand for silk was so high around the second century BCE that Chinese traders traveled thousands of miles across land and sea to sell the precious fiber. The loose network of trade routes throughout Asia and Europe were later referred to as the Silk Road.

The Silk Road helped make China one of the world's most powerful economic and political empires for more than a thousand years. By 1820, China was the world’s largest economy, accounting for nearly one-third of global production. But the country’s subsequent “century of humiliation”—which encompassed foreign invasions, internal rebellions, civil war, and international isolation—led to China’s political and economic collapse. Only in the last four decades has China begun to regain its former strength.

Today, Chinese President Xi Jinping has prioritized China’s revival (or “national rejuvenation”). China seeks to play a much larger global role and build influence in countries around the world. One of his trademark programs for accomplishing those goals is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which he frames as a new Silk Road for the twenty-first century.

Through the program, China has loaned billions of dollars to countries around the world. The focus of this initiative is to improve infrastructure in developing nations, mainly by building power plants, roads, and railways. Additionally, it prioritizes the creation of a vast digital infrastructure built upon telecommunications networks and fiber-optic cables. As with the ancient Silk Road, China’s leadership has pitched BRI as a way for countries around the world—including itself—to get rich through exchange.

Let’s take a look at how BRI benefits China to understand how countries use economic statecraft as a tool of foreign policy.

Sanctions, foreign assistance and more: What are economic tools of foreign policy (economic statecraft)?

Economic statecraft describes the various economic tools countries use—such as lending, foreign assistance, sanctions, and trade agreements—to advance their foreign policy priorities.

Certain tools are intended to influence other countries through coercion. Sanctions, for instance, seek to pressure or punish countries that violate international norms or threaten a government’s interests.

Meanwhile, other economic tools exert influence less through coercion and more through attraction. For example, countries sign trade agreements to improve their relationships. These agreements typically lower tariffs and encourage exchange that promotes economic growth. Other tools such as loans (money intended to be repaid with interest) and foreign assistance (money, services, or physical goods that one country gifts to another) can inspire improving diplomatic relations and goodwill. . Economics tools can also promote cooperation between countries on critical global issues such as climate change, cybercrime, terrorism, nuclear proliferation, and pandemics.

China leverages economic statecraft—particularly BRI loans—to advance the country’s foreign policy agenda.

To learn more about foreign assistance, check out A Brief History of U.S. Foreign Aid.

What is the Belt and Road Initiative?

In 2013, President Xi announced BRI, an infrastructure program that has been endorsed by nearly 140 countries. Through BRI, Chinese banks have funded the construction of power plants, railways, ports, smart cities, high-speed phone networks, and even indoor ski slopes. Its partner countries account for two-thirds of the world’s population. Although the Chinese government does not publicize the extent of its portfolio, U.S. investment firm Morgan Stanley has predicted the government could spend up to $1.3 trillion on BRI by 2027.

Many BRI infrastructure projects are intended to lower the cost of international trade. The result of which could increase foreign investment and reduce poverty in BRI countries. In fact, World Bank projections suggest the initiative could boost global gross domestic product (GDP) by as much as $7.1 trillion by 2040 if implemented sustainably and responsibly.

Although this research illustrates BRI’s potential to add to global economic growth, the initiative also undoubtedly benefits China. And to be clear, China is not pursuing this massive undertaking out of altruism. Specifically, China has been advancing BRI through secretive business dealings that are often not environmentally or economically sustainable. Such shortcomings in China’s vision for the future will likely undercut many of BRI’s theoretical benefits.

Economic growth

In the early 2000s, the Chinese government began promoting a new economic strategy: zouchuqu, or “going out.” This strategy encourages Chinese companies to establish markets abroad. Over time, zouchugu has evolved directly into BRI, as Chinese banks support Chinese firms building infrastructure around the world. The ultimate goal of this initiative is establishing new markets for Chinese goods and services, thus enriching China.

Several economic factors motivated China’s launch of BRI:

- Slowing economic growth: After a few decades of meteoric economic growth, China’s growth rate decreased in the early 2000s.

- Excess capacity: Many Chinese industries—including steel, cement, and automobile manufacturing—could produce far more goods than were needed domestically. BRI would provide those industries with new opportunities abroad.

- Mobilizing savings: China had many uninvested savings that could further spur economic growth.

- Impoverished interior: Although economic growth had brought affluence to China’s coastal cities, it had not fully reached China’s interior. Such wealth inequality could threaten domestic political stability. BRI aimed to connect China’s interior to its coastal cities and other countries across Asia, fueling development.

- Securing inputs: China’s manufacturing sector needed cheap raw materials. BRI infrastructure projects would create transportation networks to carry those inputs back to Chinese manufacturers.

- Reorienting global commerce: BRI would allow China to position itself—rather than the United States or Western Europe—as a center of global commerce.

When a country signs on to a BRI project, Chinese banks give the country a loan that will eventually need to be repaid. (Loans differ from foreign assistance programs like grants, which don’t require repayment.) The country that receives the loan then contracts out the work for the project to private businesses. And although China claims anyone can bid for those contracts, Chinese companies win nearly 90 percent of them. That means much of the money China lends goes to Chinese companies. Meanwhile, Chinese banks also earn interest on the loans.

After contracts are completed, though, how does China benefit from new roads, bridges, and power systems in other countries?

Many of these projects literally pave the way to new markets and decrease the cost of doing business there. New infrastructure allows companies to change their trade routes to ship products more efficiently. In fact, some sources predict the decreased shipping times will produce up to a 65 percent decrease in trade costs between China and BRI countries.

China has also recently launched a new Global Development Initiative, which aims to build on the BRI with more traditional development activities, including work to advance food security and reduce poverty in low-income countries.

Political sway

Many major donors such as the United States and the World Bank require countries to adhere to certain conditions when receiving loans. These conditions can include requirements like upholding human rights standards or establishing democratic elections. China, on the other hand, insists BRI loans come with no strings attached. Moreover, China allocates funding with the promise of indifference towards domestic affairs. In reality, research by Human Rights Watch indicates BRI has its conditions—whether explicit or implicit. BRI directly increases China’s political sway in loan-recipient countries. For instance, countries that have signed on to BRI have refrained from criticizing China’s detention of over one million Muslims in reeducation camps. In fact, after signing on to BRI projects, Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan praised “China’s effort in providing care to its Muslim citizens.” Similarly, Cameroon lauded China for “fully protect[ing] the exercise of lawful rights of ethnic minority populations.”

This influence is particularly prevalent in the arena of territorial disputes. Take the case of the South China Sea, a strategic, natural gas–rich waterway through which more than $3 trillion in trade passes every year. Six Asian countries are fighting over the tiny, uninhabited islands found there and the territorial waters surrounding them. In the past, China has used economic measures to punish countries for taking action against China’s claims in the region; for instance, the Chinese government halted shipments of fruit from the Philippines after the latter took legal action to secure its territorial claims in 2012. Experts worry that BRI gives China additional leverage to influence countries with claims to the South China Sea, many of which have already accepted BRI loans.

Additionally, China is gaining control of infrastructure in other countries through BRI. In Laos, for example, China has seized the country’s power grid after Laos was unable to pay back its BRI loans. Some experts believe China is deliberately giving out loans that recipients will never be able to repay to gain access to infrastructure abroad. Meanwhile, others worry that China’s increasing hold on overseas infrastructure could lead to devastating conflict. With heightened control over foreign infrastructure, China could tamper with another country’s energy supply or communications networks should the country act against China’s interests.

Peace and security

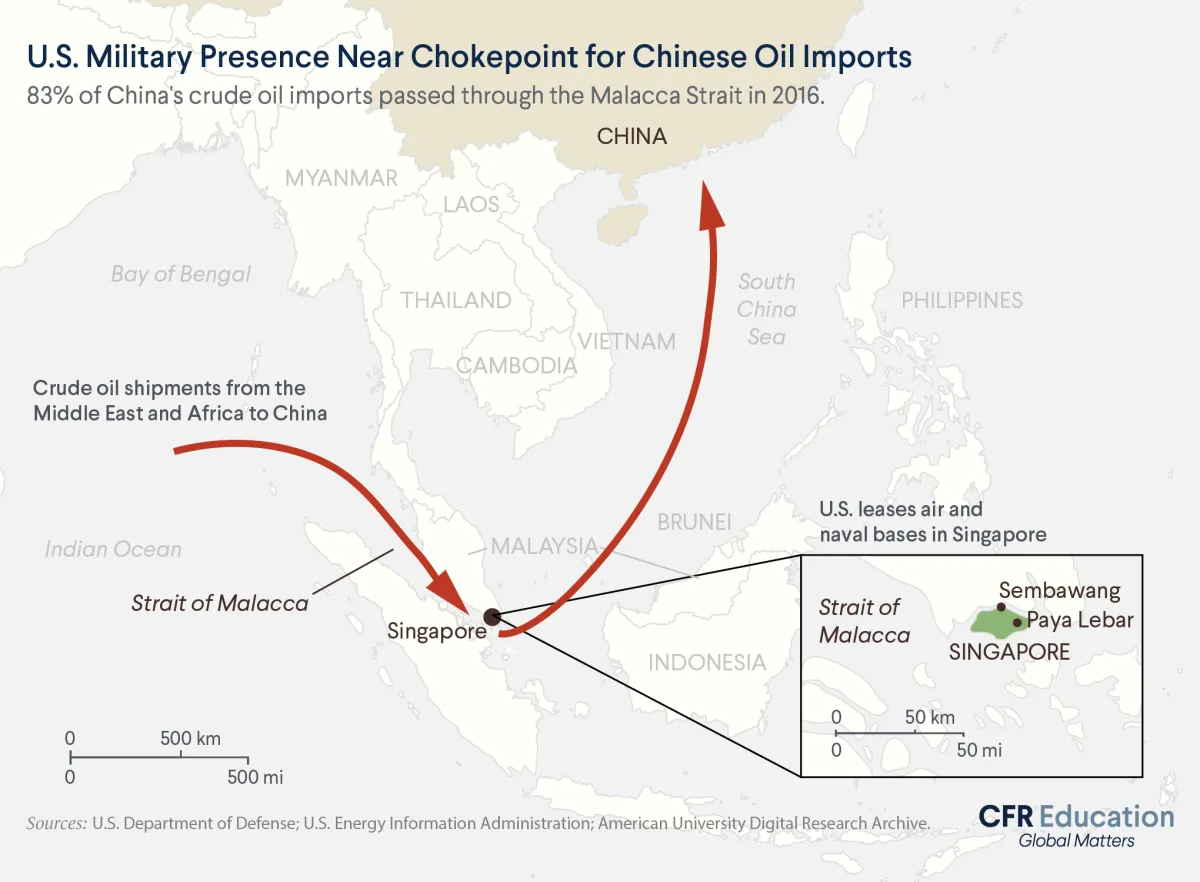

China imports more energy than any other country in the world. The majority of China’s imported oil arrives by boat via the straits of Malacca, a narrow oceanic pass between Indonesia and Malaysia. For years, the Chinese military has warned that a U.S. military presence near the straits endangers China’s energy supply. According to China, the United States could plausibly deploy its military to cut off China’s energy access during a conflict.

China has attempted to utilize BRI to address this security risk. By building and gaining access to ports around the world, China is actively seeking to diversify its energy supply chain. Unlike the United States, which maintains hundreds of overseas military bases, China has only one. Chinese firms now own, partially own, or operate at least ninety-three ports around the world. Although those ports are currently run for commercial, not military, purposes, some experts have argued they could soon become part of China’s military or intelligence apparatus. As one former Chinese general stated, “There is no need to hide the ambition of [China’s] navy. [The purpose is] to gain an ability like the U.S. Navy so that it can conduct operations globally.”

Global standing

China began its economic recovery in the late 1970s following more than a century of foreign subjugation, civil unrest, and failed government policies. To facilitate economic growth, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders initiated policies to maintain a calm and stable international environment. These policies, which became associated with the proverb “hide your strength, bide your time,” stressed focusing on domestic affairs and “hiding” China’s strength from the world. As a result, China has spent the last half-century rapidly developing without the threat of interstate conflict.

However, Xi Jinping has recently broken with that tradition. The CCP has called for China to resume global leadership on the world stage—with BRI helping to facilitate the process.

China has used BRI to reach a position of global financial leadership. Today, China’s lending for infrastructure projects exceeds the combined portfolios of every multilateral development bank on earth, including the World Bank. In fact, China has used BRI and its own state-run development banks to create a financial ecosystem that allows countries to circumvent the West. Developing nations no longer need to rely on Western-dominated development banks or Western donors like the United States for desperately needed capital. China is now the go-to financier for many countries that can’t or choose not to conform to the human rights and transparency requirements typically attached to Western loans.

BRI has also allowed China to achieve global technological influence. Through its Digital Silk Road, China offers BRI countries access to cloud services, mobile payments, smart cities, and high-speed telecommunications networks. The Digital Silk Road locks countries into China’s technological ecosystems thus opening the door to potential Chinese espionage through those networks. Those platforms have also enabled the CCP to project soft power by advancing narratives about China as a global economic and technological leader.

This is just one way the CCP has used BRI to try to reshape international perceptions of the country. Amid the COVID-19 crisis—and in response to the news that Chinese officials delayed disease reporting, undercounted cases, and silenced whistleblowers who tried to ring alarm bells about the coronavirus outbreak—China launched the Health Silk Road. This Health initiative donated and sold more than $1.4 billion worth of medical supplies to almost every country in the world. Through the Health Silk Road, China also distributed nearly two billion doses of its vaccine, Sinovac, worldwide. In several instances, China purportedly leveraged its vaccine diplomacy for political ends. For example, China pushed Paraguay to cut ties with Taiwan and pressured Brazil to strike deals with a Chinese telecommunications giant in exchange for vaccine doses.

The future of the Belt and Road Initiative

Some economic projections anticipate that BRI could result in a sixfold increase in average income in Asia by 2050. And if implemented sustainably and responsibly, BRI could lift 7.6 million people out of extreme poverty.

But concerns also exist about rising debt levels between loan-recipient countries and China. In Kyrgyzstan, for instance, debt owed to China amounts to about 70 percent of annual per capita income. And in Laos, the cost of just one BRI rail project equals half the country’s GDP. If enough BRI countries fail to repay their loans, experts warn, a global financial crisis could emerge.

BRI is ambitious, complicated, and risky. But the benefit to China could be huge, boosting the country’s economic growth and political influence. The potential is so great that the United States and its partners have announced their own economic statecraft initiative known as the Build Back Better World (B3W). In an effort to combat China’s global ambitions, the West aims to fund hundreds of billions of dollars of infrastructure projects around the world.

If successful, BRI and B3W will stand as testaments to the power of economic statecraft, showing that lending money abroad can be an effective foreign policy tool.

Now that this resource has covered the fundamentals of economic statecraft, put those principles into practice with CFR Education’s companion mini simulation, Economic Statecraft: Foreign Assistance.