What Are Economic Sanctions?

In this free resource on sanctions, learn how countries use punitive economic measures to advance their foreign policy priorities.

In 2014, North Korea launched a major cyberattack against Sony Pictures Entertainment. The attack destroyed much of Sony’s computer infrastructure and gained access to sensitive internal information. The release of a Sony film called The Interview that depicted the assassination of North Korea’s leader, Kim Jong-un precipitated the attack.

In response to the flagrant attack on an American company, the United States slapped economic sanctions on numerous North Korean officials and entities to punish the regime. The purpose of these sanctions was to further hinder Pyongyang’s military capabilities.

The U.S. response is one clear illustration of using sanctions as a tool of foreign policy. But sanctions come in many shapes and sizes. They can also have far broader consequences.

In this resource, we’ll explore the different types of economic sanctions, the reasons they are applied, and their wide-ranging repercussions.

Economic sanctions definition

Sanctions are economic measures intended to either pressure or punish bad actors—whether individuals, groups, or countries—that violate international norms or threaten national interests.

On rare occasions, sanctions can bring about regime change or a government's overthrow by a foreign power. More often, countries use sanctions to advance foreign policy goals related to conflict resolution, nonproliferation, counterterrorism, and human rights, among other issues.

Economic sanctions can either be sweeping or targeted (which are also known as smart sanctions). Following North Korea’s cyberattack on Sony, for instance, the United States targeted ten individuals for their role in supporting the North Korean regime. On the other hand, sweeping sanctions affect entire countries or major industries. Sweeping sanctions include more expansive restrictions like banning sales of certain products or prohibiting trade completely. That has been the case with U.S. sanctions against North Korea following the latter’s nuclear weapons program.

Sanctions are relatively low-cost and low-risk foreign policy tools. Consequently, they are often implemented before more expensive and deadlier forms of intervention like armed force. However, those same factors that limit the cost and risk of sanctions can also constrain their effectiveness. That means that sanctions on their own rarely lead other countries to fundamentally change their behavior or compromise vital national interests.

Who uses sanctions?

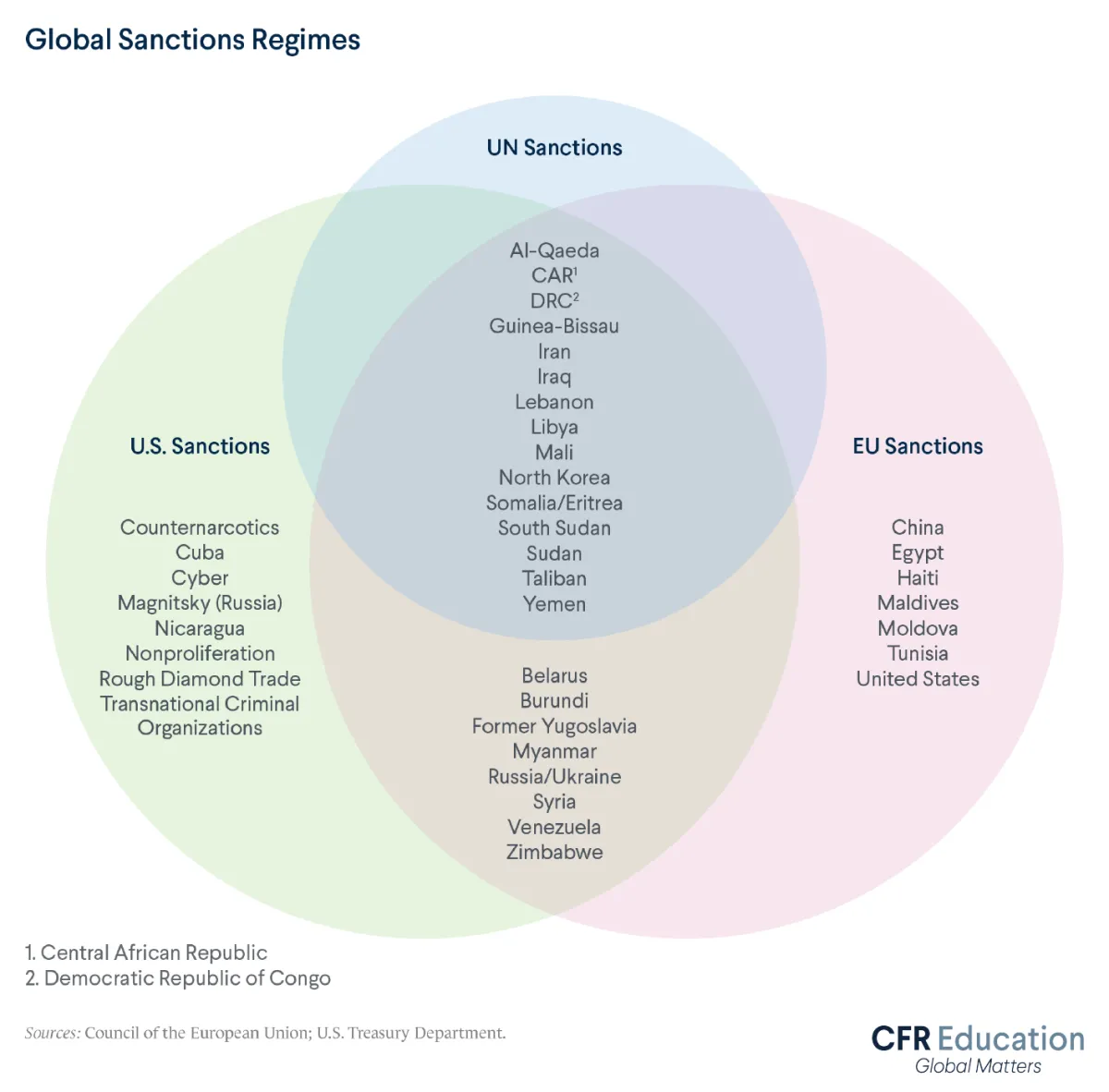

Economic sanctions can either be implemented unilaterally through individual governments or multilaterally through coalitions of countries or multinational organizations like the United Nations and the European Union.

The United States is one of the leading implementers of unilateral sanctions. Washington currently imposes restrictions on numerous governments, criminal organizations, and private or state-owned entities that threaten the country’s interests. Targets include the North Korean government, the Central America–based gang MS-13, and the Chinese technology conglomerate Huawei. The Department of the Treasury, which administers U.S. economic sanctions, has also targeted thousands of individuals such as Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony. Over the past two decades, the United States has increased its sanctions by 933 percent [PDF].

Sanctions are particularly powerful when used by countries with large economies, like the United States. Forbidding another country from doing business in the United States or working with U.S. companies has major consequences. Further, American sanctions are uniquely effective because they can restrict access to the U.S. dollar. Given that the dollar remains the world’s most widely used currency, such sanctions can inhibit bad actors from participating in international trade. Conversely, a smaller economy leveling sanctions carries far less weight.

Multilateral sanctions are often more powerful than unilateral sanctions because they combine the economic forces of multiple countries. Accordingly, the UN Security Council uses sanctions as a tool for addressing issues such as nuclear proliferation, terrorism, and international conflicts. However, building consensus around multilateral sanctions can be tricky. For the UN Security Council to impose sanctions, a majority of the fifteen-member body must approve the decision without a veto from one of the five permanent members. Because of that challenge, the UN Security Council currently has only fourteen sanctions against countries. Those countries include the Central African Republic, Iraq, Libya, and North Korea.

What are the different types of sanctions?

This resource has already covered a few different types of sanctions, but let’s explore some examples:

Asset Freezes

Asset freezes are when a government directs banks and financial institutions within its jurisdiction to withhold assets and funds connected to sanctioned individuals or entities.

For example, the United States froze the assets of numerous Russian leaders and banks as punishment following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014. The targeted individuals and entities reportedly lost access to hundreds of millions of dollars held in U.S. financial institutions. More recently, sanctions against Russia in response to the country’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 have blocked almost $330 billion of Russian Central Bank reserves. Additionally, the U.S. government has seized nearly $22 billion in personal assets of over 1,500 Russian citizens.

Travel Bans

Travel bans are when a government denies sanctioned individuals entry into its country.

In 2020, the United States imposed travel bans on fourteen Chinese officials for undermining democracy in Hong Kong. The following year, China barred several former senior U.S. officials, including former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, from entering the country. China’s travel bans were in response to actions pursued by President Donald Trump’s administration that “seriously disrupted China-U.S. relations," according to the Chinese Foreign Ministry.

Trade Restrictions

Trade restrictions are when a government cuts back on customary trade relations. This type of sanction can include banning certain types of products or cutting off trade entirely.

Take the decades-long U.S. trade embargo, or trade stoppage, against Cuba. Following the 1950s Cuban Revolution, a communist government came to power. Seeing it as an adversary, the United States cut Cuban sugar imports as an economic penalty. The sanctions were soon expanded into a total ban on trade between the two countries.

Arms Embargoes

Arms embargoes are when a government bans the sale or transfer of weapons, ammunition, and other related materials.

In 2011, the United Nations imposed an arms embargo on Libya, which was quickly descending into a civil war. The sanctions prohibited all countries from selling arms to or purchasing weapons from Libya.

Foreign Aid Reductions

Foreign aid reductions are when a government reduces the amount of money, services, or physical goods given to another country as a form of coercion or punishment.

In 1988, for instance, the United States sharply cut its foreign aid to Sudan after the Sudanese military overthrew the government and proceeded to support terrorist efforts. The level of aid dropped from $216 million in 1987 to an average of $48 million a year from 1988 to 2001.

Secondary Sanctions (or Extraterritorial Sanctions)

Secondary Sanctions, or Extraterritorial Sanctions, are when a government sanctions not just direct adversaries but also individuals, entities, and other countries supporting them.

The United States has imposed secondary sanctions on companies and countries that do business with nations such as Iran and North Korea. The mere threat of those sanctions prevents many other countries from working with Iran and North Korea in the first place. In this case, secondary sanctions contribute to the two nations’ economic isolation. Secondary sanctions, however, can cause problems when they cast too wide a net and ensnare allies and unsuspecting third parties. Such externalities can turn what could have been a common policy into a major source of friction among partners.

Do sanctions work?

In some instances, sanctions have been a useful foreign policy tool to help change regimes and policies.

Take South Africa, for example. Despite opposition from then-President Ronald Reagan, Congress used sanctions in 1986 to pressure South Africa’s government to end its racist system of apartheid. Those sanctions, which numerous other countries also imposed, compelled many multinational companies to halt business in South Africa. Due in part to sanctions that isolated the country and put pressure on its government, apartheid finally ended in the early 1990s. Sanctions were then lifted at the request of South Africa’s soon-to-be President Nelson Mandela. Mandela praised the international pressure, saying it was critical for bringing South Africa “to the point where the transition to democracy” was possible.

Quite often, however, sanctions have proven demonstrably less effective. For instance, since the 1960s the United States has imposed a strict trade embargo against Cuba’s communist government. Several restrictions on travel and the flow of money were also forced upon the regime. Yet six decades later, Cuba’s government remains in power. U.S. sanctions have also failed to effect meaningful political change in countries such as China, Iran, North Korea, Russia, and Venezuela.

One limitation of sanctions—both unilateral and multilateral—is that targeted countries can sidestep them by finding support elsewhere.

Iran has been under heavy U.S. sanctions since the Islamic Revolution in 1979. Until Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, Iran was the most globally sanctioned country. However, Russia and China routinely undermine sanctions against Iran. In recent years, for instance, Russia signed a free trade agreement with Iran. Moreover, China agreed to a $400 billion investment in Iran’s transportation, manufacturing, and energy sectors. The United States has attempted to push back: Chinese companies, for example, have been subjected to secondary sanctions for doing business in Iran. But Iran continues to avoid total economic isolation. The ongoing situation in Iran reveals that unilateral sanctions have their limits even for the most powerful economy in the world.

Over time, the effectiveness of sanctions diminishes as targeted groups, such as the Iranian government, become more adept at circumventing restrictions. Countries have been developing tactics to protect them from sanctions. Specifically, bad actors decrease reliance on the U.S. dollar to minimize the effect of U.S. sanctions. Moreover, sanctions can in some ways help authoritarian governments. Restrictions on open markets can provide regimes with more control over the economy and distribution of goods.

Another limitation is that broad sanctions on major economies are largely untenable in today’s globalized world.

Even if the United States wishes to impose broad, sweeping sanctions against China for its crackdown on pro-democracy movements in Hong Kong, human rights violations in Xinjiang, or increased militarization of the South China Sea, the United States refrains from doing so. Instead, the United States leans on narrower, targeted sanctions due to the interdependence of the U.S. and Chinese economies. As a result, sweeping U.S. sanctions would hurt not only Chinese companies but also American companies that rely on Chinese manufacturing. Ultimately, U.S. consumers would have to pay higher prices for many goods.

Additionally, sanctions can have far-reaching and dire consequences—and not only for political or business elites. More often than not, sanctions affect everyday civilians. Broad sanctions can cut the public off from economic opportunities and cause harmful supply-chain disruptions. Such disruptions can create shortages of food, gas, and medical supplies. As a result, sanctions can at times exacerbate already precarious humanitarian situations.

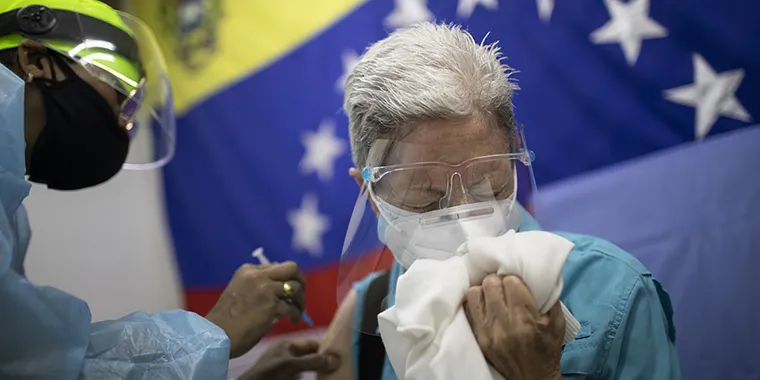

For example, look at U.S. sanctions against Venezuela during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite exemptions for humanitarian efforts, U.S. sanctions slowed or prevented critical medical products—including COVID-19 vaccines—from entering the country. The issue, Venezuelan officials and human rights organizations say, was that international financial institutions and logistics providers delayed or refused deliveries to avoid running afoul of U.S. sanctions.

Sanctions: a helpful but imperfect tool

Sanctions have their limitations: they can be insufficiently coercive, easily sidestepped, harmful to civilians, and even beneficial to authoritarian regimes.

But when implemented properly, with specific goals in mind, and combined with other foreign policy tools—such as diplomacy or armed force—sanctions can help influence others and advance a country’s foreign policy priorities.

Now that this resource has covered the fundamentals of economic sanctions, put those principles into practice with CFR Education’s companion mini simulation on Economic Sanctions.