Trains, Planes, and Shipping Containers

Three innovations shaped how people and goods move around the world today.

After centuries of travel on horseback, a series of innovations revolutionized how people and goods move around the modern world.

1830s: All aboard for fast, efficient mass travel!

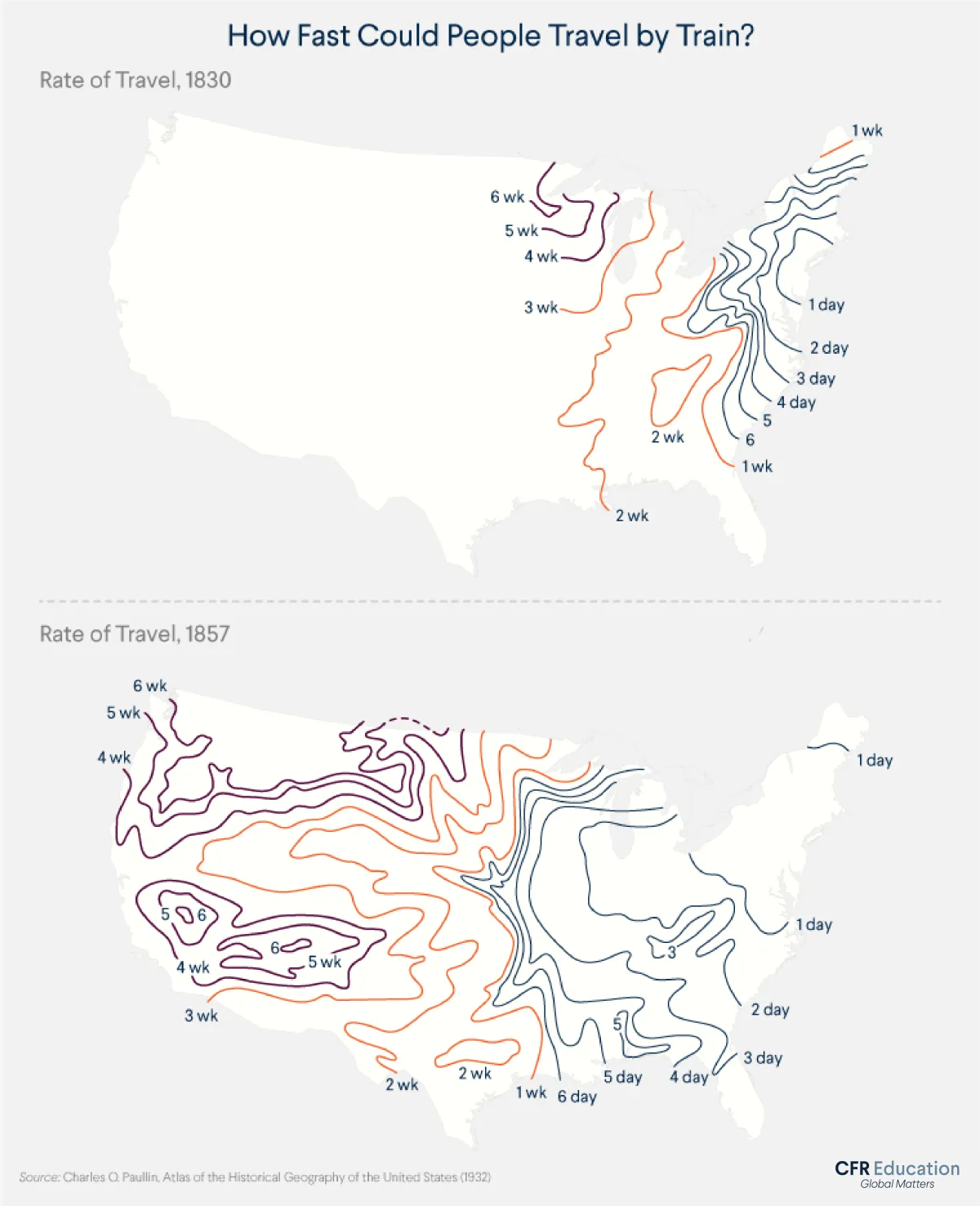

Railroads represented an astonishing innovation for the transport of people, news, and goods. For example, in 1815, it would have taken four days for news to travel between Brussels and London on horses and packet boats. By 1830, a train could cover a similar distance in one day.

Trains profoundly changed people’s lives, from how they traded to what jobs they held. The U.S. railroad system expanded from thirteen miles of track connecting two cities in 1830 to over nine thousand miles of railroad just twenty years later. By the early twentieth century, railroads were major employers in the United States. Products from one part of the country reached consumers in another, prices dropped, industry developed, settlement continued, and travel became faster and easier for those who could afford it.

But despite the railroad’s transformative effects and enduring importance, it was eclipsed by innovations in the twentieth century. The rise of cars and paved roads led to more people traveling individually and facilitated the trucking industry, especially after World War II as the U.S. interstate highway system expanded.

And then came commercial air travel.

1940s: Feel like waking up in New York and falling asleep in London? Now you can.

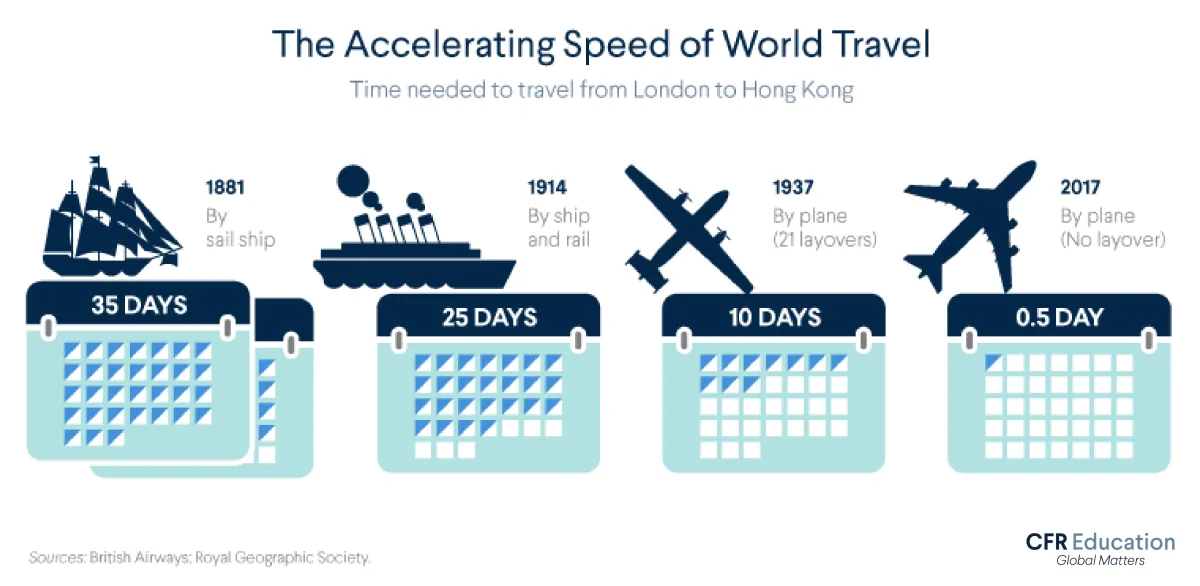

The early twentieth century saw historic moments in air travel: the Wright brothers flew the first airplane in 1903 and Charles Lindbergh flew the first nonstop transatlantic flight in 1927. But it was not until after World War II that air travel revolutionized transportation. In 1945, the International Air Transport Association, which sets global aviation standards, was established. Fast forward to 2018, when—just sixty years after the first passenger jet flew across the Atlantic— nearly 18 million travelers flew from the United States to Europe.

Not only did planes make it easier for people to travel, but they made international cargo shipping more efficient too. The 1978 Airline Deregulation Act essentially introduced a free market to the airline industry, allowing airlines to set their own fares and routes for the first time. Newly deregulated, the industry dramatically changed, with routes altering, fares dropping, passengers increasing, and companies quickly forming. Deregulation also facilitated the growth of commercial shipping enterprises such as FedEx and UPS, which were now able to use much larger aircraft than they had been. Around the same time that the Airline Deregulation Act came into effect, reduced tariffs and further technological innovations helped increase global trade and travel. The culmination of these events led to more goods crisscrossing the globe every day, which is why the seemingly mundane shipping container became a building block of the globalized world today.

1960s: Shipping companies stop thinking outside the box.

In 1956, the first container ship—the brainchild of American trucking magnate Malcom McLean—headed from New Jersey to Texas. Within ten years, the uniform, rectangular shipping container would become the standard vessel for the transportation of cargo around the world. Prior to that, cargo was not packed in a standard way; it was loaded on boats or trains in packages of all shapes and sizes. The process was disorderly, time intensive, and costly, in part because large teams of unionized workers were needed to load and unload goods, some of which could go missing along the way.

The introduction of shipping containers led to what’s known as containerization, which kicked off in earnest in the mid-1960s. This relatively simple innovation changed the world in vast ways: standardizing the containers in which goods traverse the globe drastically reduced the logistic and labor costs of shipping, which lead to a massive expansion of international trade. A study of twenty-two industrialized countries found that containerization was so efficient and streamlined that it correlated with a nearly 800 percent increase in trade over twenty years.

Efficiency was a boon for businesses and consumers. As productivity skyrocketed and technology advanced, companies saved on insurance costs, for example, as standardization and security prevented the theft of goods. They also saved money on labor costs: containerization meant they needed fewer workers. But efficiency had its drawbacks: many people lost their jobs, and some ports closed. Businesses saved money, but many families were left without a steady income.

These innovations have made life easier for most—but harder for some.

With all the talk of the innovations that have encouraged and shaped globalization, making it faster and simpler for people and goods to travel, it can be easy to slip into the assumption that these changes have all been for the better. However, every benefit comes with costs.

It’s true that people can hop on a flight before breakfast and end up on the other side of the country—or the world—for dinner. But in doing so, they are emitting several tons of carbon dioxide, contributing to climate change, and could be enabling the spread of deadly diseases. You can order clothes or shoes online and have them delivered to your doorstep the next day. However, you would likely be supporting an industry that takes advantage of low wages and weak labor laws in developing countries and displaces jobs as it moves from country to country seeking lower operational expenses.

It can be easy to forget that the conveniences taken for granted today didn’t always exist. But understanding how drastically—and quickly—advancements like the railway, the jet plane, and the shipping container transformed the world can help us appreciate globalization’s many contradictions.