How Energy Conservation Can Help Fight Climate Change

Conserving energy and maximizing efficiency means less strain on electricity grids and fewer greenhouse gas emissions. But is it working—and fast enough?

In 2022, a Nobel Prize–winning Italian physicist recommended that people should turn their stoves off halfway through cooking their pasta to save energy. The suggestion sparked shock— and sometimes outrage—among other Italians. One chef responded in the media, “Let’s leave cooking to chefs while physicists do experiments in their lab.”

Behind that somewhat quirky episode is an example of a question many climate researchers and policymakers are increasingly thinking about: how to use less energy.

Fighting climate change involves making sweeping changes to how societies use energy. Countries are seeking ways to increase the amount of their energy use that comes from renewable sources. Those changes also entail electrifying parts of the economy that traditionally run on fossil fuels. That can include swapping gas-powered cars for electric vehicles or substituting gas stoves for electric ones.

Developing renewable energy and electrifying the economy are vital steps, but they take time. Meanwhile, rising demand for electricity could strain the grid, and a considerable portion of the energy produced today goes to waste due to inefficiency and overuse. Accordingly, another part of fighting climate change involves governments, businesses, and even individuals taking steps to streamline and reduce their overall energy consumption.

Such steps involve two related and often overlapping strategies: generating and using energy more efficiently and using less, or conserving energy, wherever possible.

This learning resource will cover how energy efficiency and conservation can help fight climate change. It will explore several strategies that can reduce energy use and look at the challenges facing future conservation efforts.

Why Reducing Energy Consumption Is Important

Renewable energy is rapidly gaining ground around the world, but not fast enough. To meet the goals laid out in the Paris Agreement, renewable energy capacity needs to triple by 2030. Currently, it is on pace to fall short of that goal by up to 10 percent. Meanwhile, demand for energy is rising globally and will likely continue to do so as economies develop.

Electrification, similarly, would need to double in pace to reach global climate goals for 2030. Electrification can help bring down emissions, but as long as most electricity generation comes from fossil fuels, it’s not enough on its own. Moreover, electrification will also drive up demand for electricity; global electricity demand is already increasing significantly. That is fueled, in part, by emerging technologies and industries, such as artificial intelligence, and the development of electric vehicles.

By some estimates, global electricity demand could rise by up to 75 percent by 2050. Such an increase could strain the ability of existing grid infrastructure to provide people with electricity. It would slow the adoption of electric options, raise costs for consumers, and threaten their reliable access to electricity.

That is where efficiency and conservation come in. Even if renewable energy cannot replace fossil fuels fast enough, using energy more strategically can help fill the gap. By one estimate from the International Energy Agency (IEA), emissions in 2017 were 12 percent lower than they would have been without efficiency measures that had been put in place since 2000. What’s more, as demand for electricity continues to rise, conservation and efficiency measures can help slow that growth. That would reduce the strain on the grid, and even lower energy costs for consumers in the process.

How to Increase Energy Efficiency

New practices and technologies can allow countries to do more with less energy. Doing so not only helps fight climate change but also saves energy consumers money. Let’s look at some examples.

Buildings: Homes, offices, shops, and factories all require energy for lighting as well as heating or cooling. In fact, buildings and the electricity they use account for roughly one-third of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. Improved materials and designs for new buildings and modifications to existing ones can help reduce that figure.

Some energy-efficient technologies and materials include

- high-performance insulation, such as vacuum insulation panels that minimize heat transfer in and out of buildings;

- energy-efficient windows that incorporate coatings to reflect a certain amount of light or multiple panes to provide better thermal insulation;

- smart heating or cooling systems that adjust settings automatically to maintain a comfortable temperature without running constantly at the same level; and

- energy-efficient appliances, such as light-emitting diode (LED) lightbulbs or refrigerators with improved insulation to prevent temperature loss.

Industry: Industrial activities like manufacturing and chemical processing are directly responsible for 24 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Most are from the intense heat that those processes require. In 2018, nearly 40 percent of the heat produced in U.S. industrial processes was lost as waste.

Just like home appliances, industrial machinery can be made more efficient. Methods of heat capture and storage, for example, can help recycle some of the heat from industrial processes to reduce waste. In other cases, new and less energy-intensive industrial processes can increase efficiency. In chemical processing, for example, separating useful chemicals from a mixture often involves boiling away the unwanted substance or distilling it until only the useful chemical remains. But researchers are developing new techniques that use membranes to separate chemical mixtures without heat. Such techniques can use up to 90 percent less energy than traditional distillation methods.

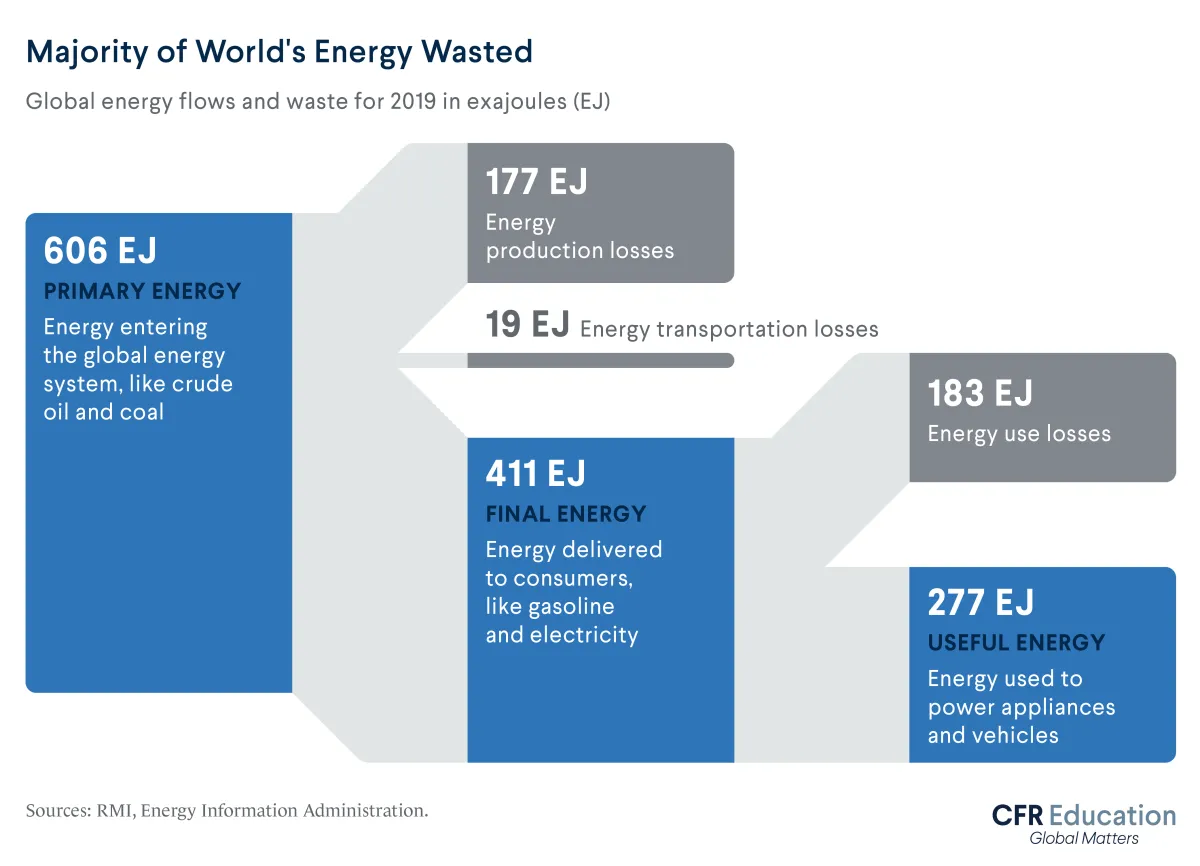

Electricity: Power plants convert the energy from one source, such as natural gas, wind, or nuclear fission, into electricity. But they don’t convert all of that energy to electricity. In fact, they don’t even convert half of it. Of all the energy used in U.S. power plants, only 41 percent [PDF] actually makes it to consumers as electricity.

A lot of that loss has to do with how power plants generate electricity. Most power plants are thermal. They use heat to produce steam, which spins a turbine that generates an electric current. In most thermal power plants, the majority of the heat generated in that process is wasted. That means, in a lot of cases, humans are emitting greenhouse gases by burning fossil fuels and not even capturing all the energy they could from the process.

Several techniques can make thermal power plants more efficient. For instance, researchers have experimented with coatings on the inside of power plant condensers. The coatings would allow steam to condense back into water more efficiently. Waste heat recovery systems can also capture some of the excess heat from the generation process and use it for building heating or industrial processes.

One of the best ways to address that problem is by switching to renewable energy. Even though renewable sources aren’t necessarily more efficient than thermal plants, the energy lost in converting wind or sunlight to electricity doesn't come from burning fuel that releases greenhouse gases.

It’s not just electrical generation that suffers from inefficiencies. Transmission and distribution networks—which carry power from generators to consumers—can also experience losses that damage efficiency. Updating aging infrastructure can help reduce those losses. Introducing smart grids can also improve efficiency. Smart grids employ sensors to monitor electricity usage in real time, enabling power plants to more precisely dial generation up or down to meet demand without wasting energy.

How to Conserve Energy

Energy consumption can also be reduced through conservation. It involves energy-saving actions from individuals and organizations. Those include

- turning off or unplugging lights and other electronic appliances when they’re not in use;

- adjusting thermostat or air conditioning settings to use heating and cooling less intensively;

- limiting hot water use by taking shorter showers and washing clothes in cold water; and

- using smaller appliances when possible, such as a toaster or microwave instead of a full-size oven.

Maybe reducing household and business energy use seems small in comparison with some of the larger measures governments are implementing to fight climate change. But those small changes can add up. For example, one study [PDF] found that an average thermostat adjustment of 1°F across the United States could lead to a 0.5 percent reduction in total emissions.

What Governments Can Do

Energy efficiency and conservation isn’t just about individual choices. Governments at the national and local levels can use several strategies to encourage businesses and individuals to reduce their energy consumption and to spur the development of more efficient technologies. Let’s explore some examples:

Standards and regulations: Governments can adopt regulations requiring that new buildings or appliances meet certain efficiency standards. For example, the Joe Biden administration issued standards for lightbulb efficiency that will require most household lightbulbs to produce more than 120 lumens (a unit of brightness) per watt. Those standards, almost ten times more efficient than an average incandescent bulb, aim to spur continued development of more efficient products among manufacturers.

Incentive programs: Governments and utility companies can offer incentives like rebates or tax credits for consumers who voluntarily switch to efficient products or adopt energy-conserving behaviors. In Germany, for example, households can receive up to 20 percent of their renovation costs back if they make efficiency upgrades.

Some efficiency and conservation programs also aim to safeguard against strain on the electrical grid. They ask customers to shift activities that use a lot of electricity, such as laundry or dishwashing, to different times of day when demand is lower. In 2022, 448 electric utilities in the United States had similar efficiency programs. Those resulted in an estimated reduction of 28.2 billion kilowatt-hours in total annual electricity consumption.

Public information: Governments don’t always have to regulate or incentivize energy-conscious decisions. They can also coordinate action by requesting that residents adopt certain behaviors and by providing information that helps consumers make informed choices.

In 2022, for example, Finland launched a campaign to reduce electricity use by encouraging citizens to cut back on sauna use to help manage energy shortages caused by the war in Ukraine. The Down a Degree initiative urged people to lower their thermostats and limit sauna time, especially during peak hours, as part of broader efforts to prevent energy shortages during winter.

In the United States, the federal government administers the Energy-Star program, which labels buildings and electronic devices that meet certain efficiency standards so consumers can easily identify them. In 2010 alone, that program enabled consumers in the United States to avoid emissions equivalent to thirty-three million cars.

Does It Work?

Progress toward better energy efficiency and conservation practices could play an essential role in the reduction of global emissions. By 2030, efficiency improvements alone could deliver more than one-third of all the emissions reductions required between now and 2030 to meet a net-zero-by-2050 target. And progress toward those goals is emerging. In 2023, 133 governments pledged to double the global rate of energy-efficiency improvements by 2030. Toward that goal, governments accounting for more than 70 percent of global energy demand adopted new or updated efficiency policies in 2024. Still, the IEA warns that current trends fall short of meeting that goal and that more ambitious policy steps are needed.

In many cases, the technologies to reduce energy use are already available or being rapidly developed. But implementing them at the scales required will need continued attention and resources from policymakers, businesses, and individual consumers around the world.