How Climate Change Reduces Biodiversity

Climate Change is straining the earth’s ecosystems. Learn how humans can adapt to protect them.

Humans can’t ignore the natural world. We rely on ecosystems—diverse and interconnected communities of living things and the environments they inhabit—for our food, livelihoods, and shelter. Even if we live in cities, we’re still connected to distant environments like grasslands, forests, and oceans. Each unique ecosystem is home to vast networks of different species, all of which play different roles in maintaining that ecosystem’s health.

Maintaining many and various organisms in an ecosystem—its biodiversity—is an essential part of that ecosystem’s health. It’s also crucial for humans. Go to the grocery store and think about the many different organisms it takes just to stock the seafood counter. It’s not just what you see in front of you. A salmon, for example, eats insects or smaller fish. Those, in turn, eat plants or smaller organisms. Plants in the water filter out pollutants. If one of the links in that chain broke, the whole ecosystem could unravel.

In nearly every country, ecosystems are under stress. Climate change and human activities like agriculture are causing species to move or die off, reducing biodiversity across the globe and threatening the very things we need to survive and thrive.

Countries have adopted several strategies to defend against biodiversity loss. Those include protecting delicate ecosystems from human influence, managing land and resource use, and restoring damaged environments. Countries tend to use environmental protections as a kind of balancing strategy. Think about it like a scale. On one side is what humans take from nature: resources like crops for food and organic material for clothing and other products. On the other side is how nature recovers, with processes like nutrient regeneration in soil and forest growth. To keep the scales in balance, societies try to make sure they’re repairing ecosystems as fast as they’re depleting them. Conservationists warn that they are already failing in that regard. Many countries’ policies don’t sufficiently account for the value of ecosystems, and they are at great risk of being depleted.

But climate change has made environmental protection more challenging; shifting weather patterns and rising temperatures will disrupt delicate ecosystems and make it harder for them to recover. What’s more, economies are degrading environments faster than they can replenish to fuel their growth. The scales are becoming more and more difficult to balance. That’s a problem both for the earth and for all of us.

In this resource, you’ll learn how climate change endangers biodiversity and challenges environmental protection efforts. Then you’ll explore how people and governments around the world can adapt their practices to face those realities.

What’s going wrong?

Scientists warn that Earth is experiencing a “sixth extinction”—a mass extinction event on par with the one that killed the dinosaurs sixty-five million years ago. Plant, animal, and invertebrate species are going extinct thirty-five times faster than they have previously over the past million years, due to the combined effects of climate change, human-caused habitat destruction, and the wildlife trade.

Climatic environmental damage is primarily caused by warming temperatures, changing weather patterns, and extreme weather events:

- Global warming: Rising temperatures can put stress on many species, causing them to move in search of cooler climates or die off. In the United States, for instance, warmer temperatures can accelerate the growth of cheatgrass, an invasive species that degrades soil nutrients and hurts crops.

- Changing weather patterns: Climate change also alters environmental elements like precipitation, soil health, and air quality. The normal weather patterns that ecosystems developed over centuries are quickly changing. Those patterns affect how plants grow and how animals behave.

- Extreme weather: More frequent and severe weather events, like wildfires, also threaten ecosystems by destroying habitats. For example, the 2019–20 Australian bushfires burned nearly nineteen million hectares of land, killing or displacing almost three billion animals.

But the damage can be exacerbated by other human activities, including the following:

- Farming: Nearly half of the world’s land surface is used for agriculture. Unsustainable or careless farming practices can deplete the soil, turning once-fertile areas into deserts.

- Resource extraction: Practices like logging, mining, or oil exploration can all disrupt animal habitats and release harmful pollutants into the surrounding environment.

- Development: City construction and infrastructure projects like roadways and hydroelectric dams can destroy animal habitats or cut off migration patterns.

- Pollution: Pollution can mean light pollution, noise pollution, and material pollution, like plastic waste, all of which can disrupt habitats and species migration.

Through a combination of those factors, humans have already degraded an estimated 20 to 40 percent [PDF] of the world’s land, meaning they have reduced its ability to support ecosystems. That is one of the core drivers of biodiversity loss.

Biodiversity loss isn’t just about the ecosystems themselves. It also threatens human populations. Let’s look at a specific example: coral reef endangerment and how it can damage human lives.

Warmer water can cause coral to expel algae living in their tissue, turning it completely white—a process called coral bleaching. If the temperatures stay high, the coral will never let the algae back in and it will die. Warming that is too sudden and extreme can make it difficult for organisms like coral to adapt. Between 2014 and 2017, 75 percent of the world’s coral reefs experienced some level of bleaching. In the next twenty years, up to 90 percent of the world’s coral reefs are projected to die due to warming oceans. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that if global warming exceeds 2°C, coral reef loss could be irreversible, with 99 percent of reefs dying out.

Reef death has massive consequences for ocean ecosystems and for people. One-quarter of all marine life relies on coral reefs for food and shelter. In turn, many communities, especially in small island states, rely on reef fish for up to 90 percent of their dietary protein. What’s more, reefs also help protect shorelines from storms by absorbing wave energy. Without coral reefs, humankind will have less to eat and face greater danger from the extreme weather that comes with climate change.

Reefs are far from the only threatened ecosystem that can affect human life. Many other ecosystems provide essential services to humanity, such as pollinating crops or producing medically beneficial compounds. Over time, biodiversity loss will have cascading effects that will threaten every aspect of the world economy, and even the ability of Earth to support humanity itself.

What can we do to protect ecosystems from climate change?

There are three main categories of environmental protection: preservation, conservation, and restoration. Let’s take a closer look at each of them.

Preservation focuses on protecting important or endangered ecosystems from human interference. National parks, wildlife reserves, and fish nurseries are all examples of preservation strategies at work. Ideally, those strategies keep natural spaces as untouched as possible to allow ecosystems to regenerate and thrive.

Often, however, preservation efforts clash with societies’ economic priorities. It’s a difficult decision for policymakers to sacrifice economic opportunities for environmental protection, especially in developing economies. In 2020, for example, Cambodia put a ten-year ban on hydroelectric dams that could damage nearby wetlands along the Mekong River. However, demand for more electricity put the dam project back on the table within just two years.

Climate change is also introducing new stressors. Even in protected areas, some plant and animal species are dying out because of warming temperatures or new weather patterns. In California’s Joshua Tree National Park, for instance, heat and drought have driven steep declines in bird populations. Other populations are moving out of protected areas in search of more favorable locations. Although preservation remains an important factor in combating biodiversity loss, experts are increasingly calling to combine it with new approaches that adapt to changing realities.

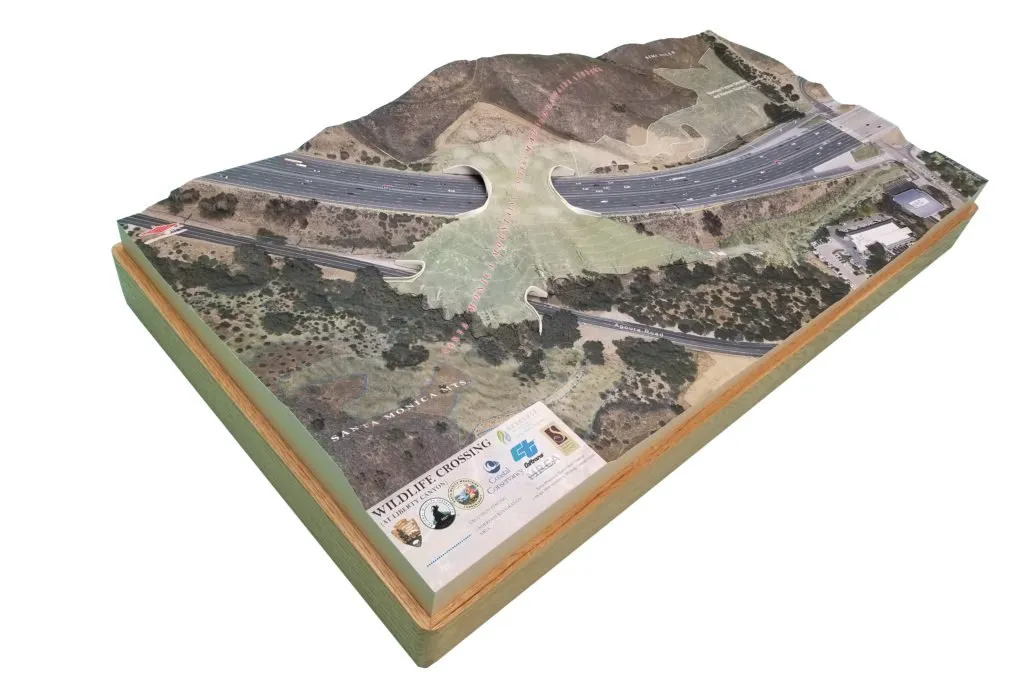

Conservation strategies aim to responsibly use nature in ways that reduce environmental damage. In general, conservation can help balance the economic needs of a society with its environmental protection efforts. For example, whereas preservation strategies would restrict roadways being built through protected areas, a conservation approach could mean building wildlife bridges over highways to allow animal populations to move more freely. Building wildlife bridges would not completely prevent biodiversity loss, however, though it would help stem the damage. In cities, coexistent approaches could include motion-sensing streetlights that reduce light pollution.

Conservation also includes altering human practices to be more sustainable. That includes regulating logging, fishing, and agricultural practices to ensure that the environment can regenerate as quickly as it’s degraded.

Restoration means repairing damaged ecosystems. Unlike preservation, it involves active human efforts. This can include replanting forests or reintroducing endangered species to an area they had previously left.

Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay, for example, formed the Trinational Atlantic Forest Pact to protect lands threatened by centuries of logging and agricultural expansion. Through a combination of active planting and natural growth, the pact has so far restored seven hundred thousand hectares, an area roughly the size of Puerto Rico. The pact also aims to create one million green jobs by 2030 to ensure that the three countries’ environmental protection efforts can also bring economic benefits.

Restoration efforts are an invaluable tool to slow biodiversity loss. They can also help combat climate change. Replanting forests, for example, helps absorb carbon from the atmosphere. However, they can take a long time to succeed. Forests, for instance, can take decades to fully grow. And often, restoration programs cannot completely return ecosystems to the way they were before.

Ultimately, no single one of those approaches is perfect, and none can succeed on its own. Especially as climate change creates unpredictable conditions, experts are now calling for more flexible environmental protection efforts. That could mean creating dynamic fish preserves with boundaries that move along with shifting species.

Who can protect ecosystems from climate change?

Environmental protection isn’t necessarily cheap. Policymakers, therefore, have a large role to play. Governments can fund infrastructure projects that support environmental goals and still lead to economic development. In the United States, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which congress passed in 2022, promises $19.5 billion to support environmental protection efforts. The IRA is forecasted to create an average of one million green jobs each year over the next decade.

But adapting environmental protection efforts will need a global push. After all, ecosystems exist across borders: different countries fish in the same oceans, rivers flow through multiple nations, and animals migrate between hemispheres.

Several current international agreements are already in place to address those realities. They include:

- the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, signed in 1973—one of the oldest international conservation agreements, whose progress representatives meet every two years to discuss;

- the Convention on Biological Diversity, signed in 1992, which promotes sustainable development and conservation; and

- the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction agreement, signed in 2023, which recognizes the need for legal instruments to conserve marine life.

Those agreements are important but insufficient. So far, they have failed to slow biodiversity loss worldwide. Some experts estimate that human activity is causing species to disappear at one thousand times the normal rate.

Some recent efforts are hoping to correct those failures. In December 2022, roughly 190 countries approved a UN biodiversity agreement. The goal is to protect roughly a third of the earth’s land and seas by 2030. Although not legally binding, the agreement also puts forward financial commitments. Much of the world’s biodiversity exists in the Global South—and within many countries that can’t afford costly environmental protection efforts. The UN agreement earmarks $30 billion in biodiversity financing for poorer countries.

Ultimately, societies’ ideas about environmental protection are beginning to change. But the issue will need continued attention, flexibility, and resources from governments around the globe. After all, human beings cannot exist without healthy ecosystems.