The 1900 McKinley vs. Bryan Election and U.S. Strategy in the Pacific Today

War in the Philippines signaled a new era for American foreign policy—and sharply divided the American people.

Setting the Scene

Imagine you are there: It is February 4, 1899. In Washington, DC, the Senate is ready to approve a treaty with Spain, which will give the United States control over the island nation of the Philippines. The United States already occupies the country. In two days, it will call the Philippines its own.

At this same moment, it is night in the Philippines. Tensions brew as militias refuse to cede political control to the Americans. Outside a disputed village, a group of Philippine soldiers encounters an armed American guard. The guard challenges them. But the soldiers do not respond. It is unclear who shoots first, but soon a firefight erupts. The U.S. Army, having already planned an attack, moves against the Filipinos. The fighting will go on for the next three years.

The United States calls the conflict an insurrection. But the Filipinos consider it a war for independence. A year ago, Spain ruled the Philippines. The Spanish had sought to keep the people fragmented, imposing the Spanish language and Catholicism. The people of the Philippines protested the rule of the Catholic Church and the lack of Filipino representation in the government. They revolted several times. Each time, the Spanish violently put them down.

When the United States attacked the Spanish, the Filipinos joined them. The Philippines soon declared independence. But when American forces came ashore, that independence would disappear.

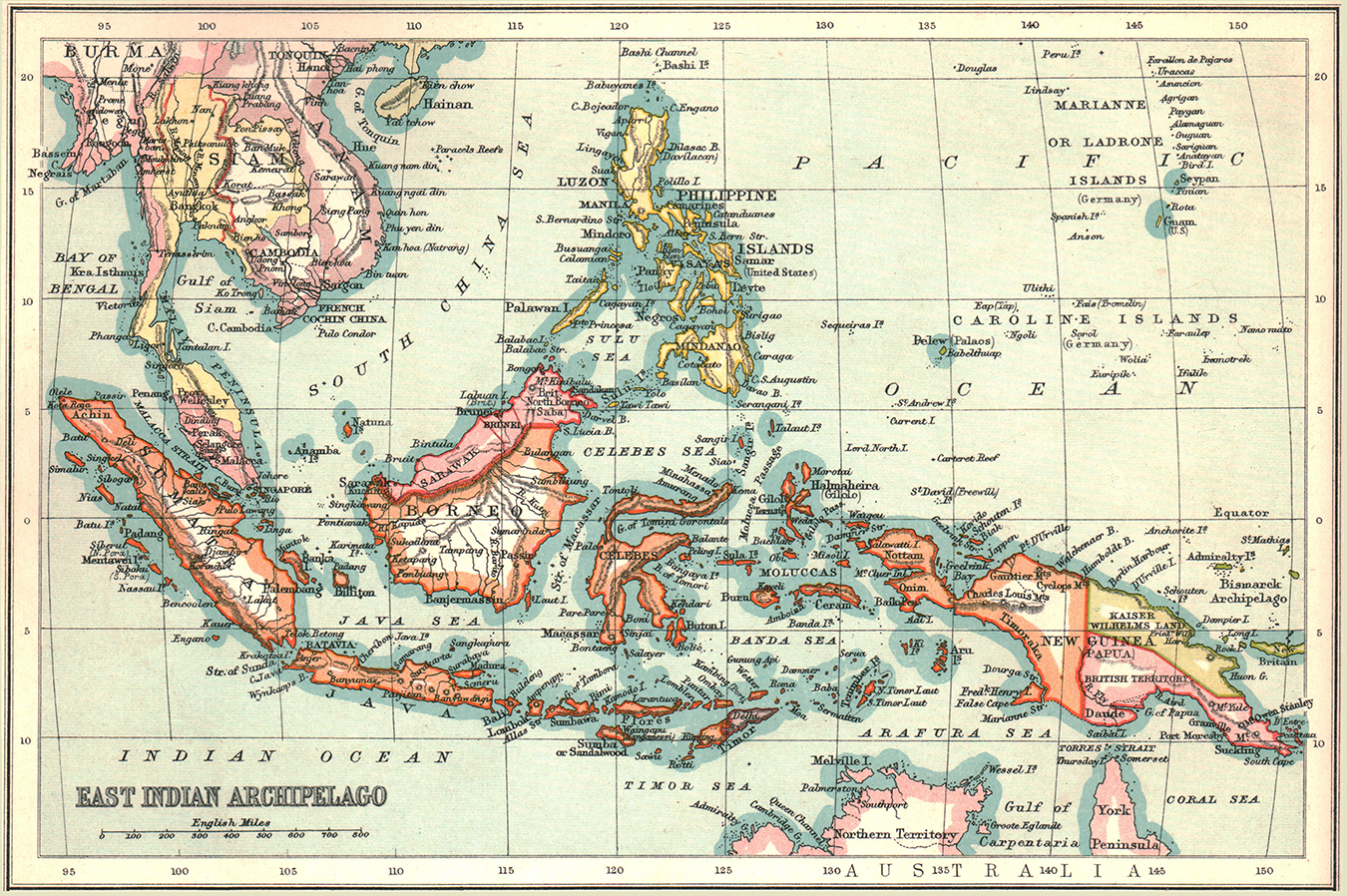

For the United States, the Philippines is an economically and militarily strategic asset. Like other islands once controlled by Spain, the Philippines can help the United States grow its navy and extend its power across the Pacific. To the Filipinos, that looks a lot like Spanish colonialism; by February 1899, they are ready to fight again.

In Washington, over eight thousand miles away, President William McKinley faces growing opposition. Public opinion about the war in the Philippines is mixed. Some Americans see it as necessary to avoid losing the island to Japan or Germany (which controlled many small Pacific islands at the time). Others see it as an economic opportunity. But many are against the war and what it means for the United States. They see their country entering an age of empire.

McKinley himself worries about annexing the Philippines, having originally called such an act “criminal aggression.” But public opinion and pro-annexation arguments persuade him, and he chooses that course anyway. On February 6, 1899, as American soldiers clash with Philippine rebels, Congress approves the treaty with Spain. By the fall of 1900, as the presidential election approaches, critics have a stronger word for the war: imperialism.

Divided over the Philippines—and their country’s role in the world—Americans head to the polls.

The 1900 Election: McKinley vs. Bryan

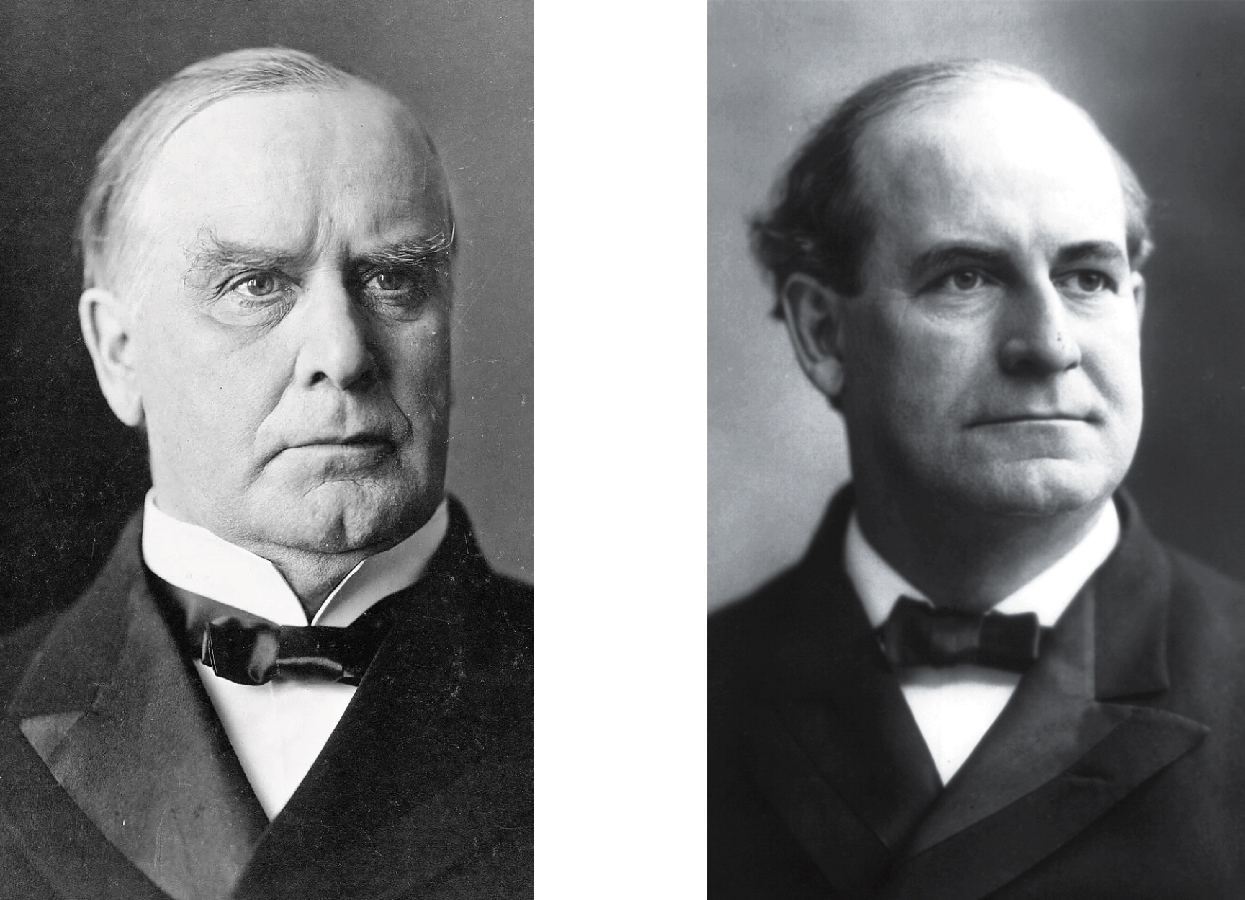

The 1900 election was a rematch. The president’s opponent, William Jennings Bryan, had risen within the Democratic Party just four years earlier. He was a talented public speaker, and he forged a strong following. But his oratory abilities were no match for the Republicans, who managed to convince American voters in 1896 that Bryan would be bad for the economy. So the former Ohio representative, William McKinley, was instead elected into office.

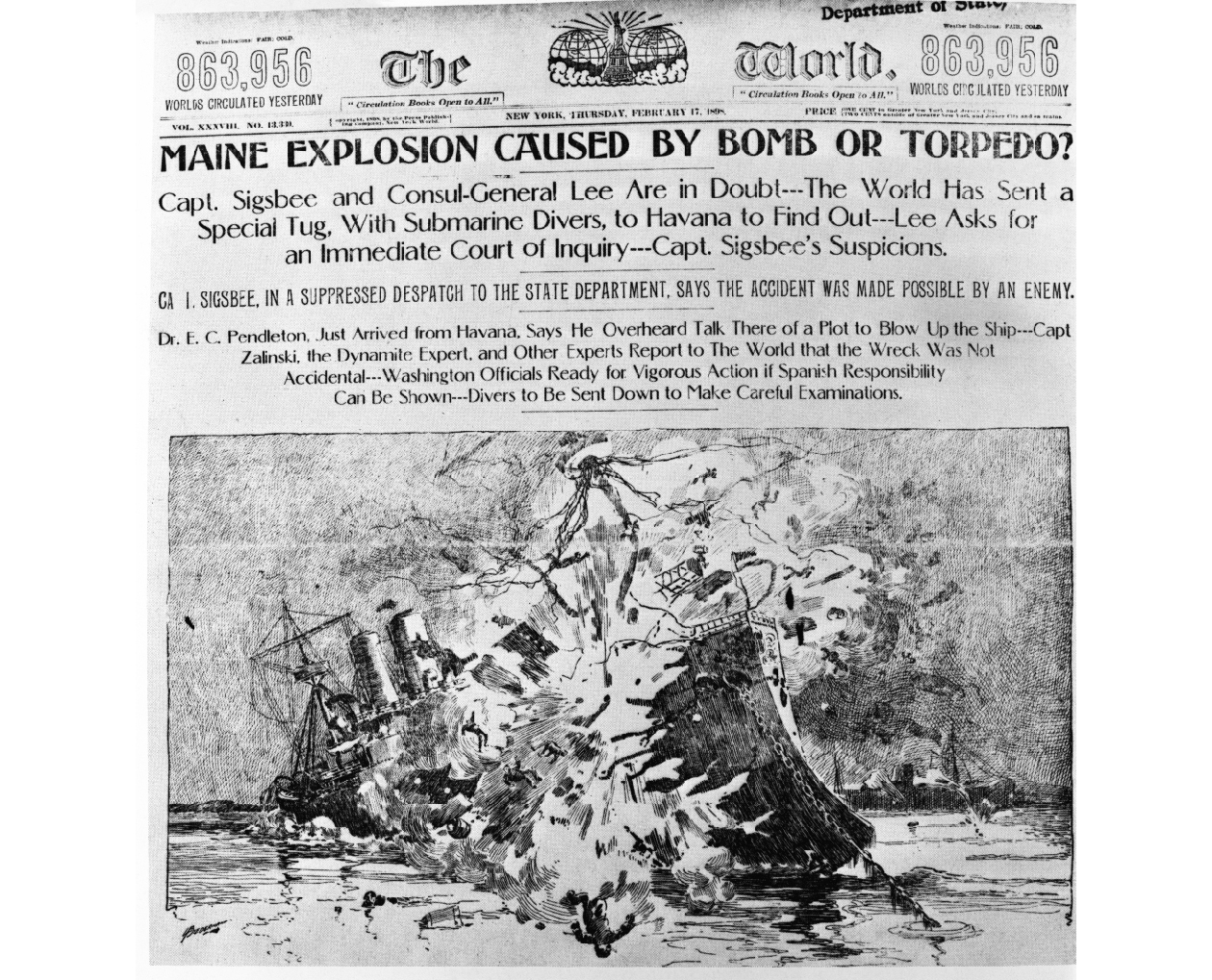

McKinley spent much of his time in office worrying about public opinion. Even in 1898, he was thinking about the next election. In February, an American naval vessel, the USS Maine, blew up outside Cuba—killing 260 sailors. The newspapers and the American public, blaming Spain, wanted war. Fearing voter wrath in the 1900 election, and seeing an economic opportunity in Cuba, McKinley acquiesced.

The battle against Spain began in the Philippines, where the American Navy quickly wiped out the Spanish fleet. The same happened in Cuba. The Spanish withdrew from both, leaving the United States in control. But although Cuba was smaller and closer to U.S. shores, the Philippines was different. It was a country of seven million people, some of whom were already resisting American occupation. Territorially, the country was larger than England. It was also an ocean away. Once again, McKinley initially waffled. What should he do with the Philippines?

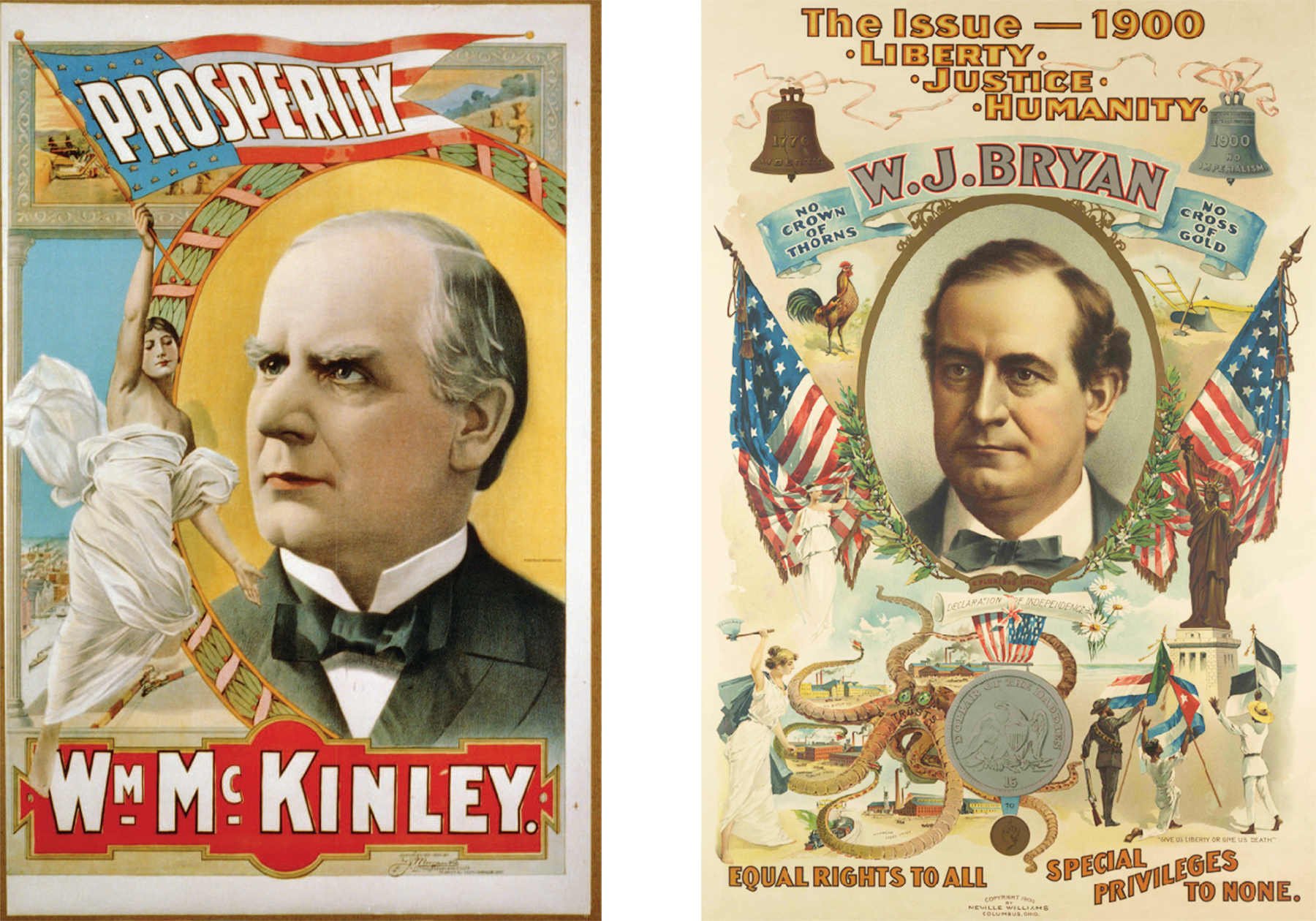

His eventual decision to annex the country, declaring it part of the United States, proved contentious. In the election year of 1900, Bryan seized on McKinley’s decision. The Philippines, along with Cuba and Puerto Rico, which had also been taken in the war against Spain, became flash points for Bryan. “Any government not based upon the consent of the governed is a tyranny,” Bryan’s Democratic platform proclaimed. The Democratic Party saw American presence in the Philippines as tyranny. They warned that “imperialism abroad will lead quickly and inevitably to despotism at home.”

Democrats were framing the 1900 election as a battle over the future of American democracy.

The Ballot Issue Then

In 1896, voters worried about other issues. Those included tariffs, or taxes on imported goods, as well as debate over the gold standard. This was an election concerned with the economy. Bryan and McKinley were at war over American progress—in the United States.

But in 1900, the United States was also looking beyond its shores. It was quickly becoming an economic and military power. Bryan and McKinley were now at odds over the U.S. role in the world.

Neither Bryan nor McKinley were opposed to territorial expansion. Both believed in protecting the United States from foreign authority. But they disagreed on how the country should govern its new lands. Bryan and the Democrats believed that “the Constitution follows the flag.” Anywhere the United States expands its territory, they argued, should become part of the United States—meaning its citizens should become American citizens, protected by the Constitution.

However, many Democrats argued such expansion was not possible in the Philippines. According to their 1900 party platform, the Filipinos would endanger “our civilization” if they became American citizens. The Democrats argued instead for Philippine independence. But they didn’t clarify what independence would mean—or what form of government it would take.

The Republicans under McKinley saw the situation differently. Their party platform continued to emphasize increasing American prosperity, which included expanding trade and influence in Asia. The Philippines was not the only Pacific island captured from Spain; Guam was taken too. The independent Republic of Hawaii was also annexed during the war. That expansion helped the United States further pursue trade in China, an increasingly competitive market among European powers. The Philippines was, therefore, important in that endeavor.

But while Republicans also called for self-governance, they continued to refer to Philippine resistance as “armed insurrection.” Their policy toward the Philippines assumed the people were not yet capable of self-rule, a conclusion reached by the U.S. military. American officials would have to first train and prepare the people for popular self-government, Republicans argued. That transition would take time—and so, according to such logic, the United States needed to stay.

The Republican Party spent millions on the election, producing 125 million campaign documents, including postcards and newspaper inserts. Campaign ads promised continued prosperity. The Democrats maintained their anti-imperialist campaign.

The Democratic Party’s efforts weren’t enough. McKinley and the Republicans won decisively in November. But Bryan’s concerns about U.S. military aggression were not misguided. In the Philippines, the United States proved to be as oppressive as the Spanish. The war continued after the election, and roughly two hundred thousand Filipino civilians had died in the fighting before it ended in 1902.

The Ballot Issue Now

U.S.-Philippine relations have evolved since McKinley’s time—and since the Philippines gained independence in 1946. But overall, the two countries have strengthened their economic and military ties. In 2014, both signed a defense cooperation agreement, which allows the U.S. military to send soldiers and ships to bases in the Philippines. That cooperation was reinforced in early 2024 by the Biden administration, which added four new American military bases.

Military cooperation with the Philippines will probably not be on American voters’ minds this November. But the Pacific region likely will.

In recent years, China’s navy has become increasingly aggressive in the Pacific, particularly in the South China Sea. China has antagonized countries in the region, like Malaysia and Vietnam, by claiming territorial control of the sea; they’ve even attacked Philippine boats there. As in 1900, the Philippines represents a strategic military position in the region. It provides access to the South China Sea, and so acts as a staging ground for U.S. forces.

How would the U.S. military make use of the Philippines? One scenario involves Taiwan. Although many issues shape U.S. competition with China today, Taiwan is a significant one. The United States opposes China’s ongoing threat of military action against Taiwan, a key partner for the United States in the Pacific. The Philippines is less than ninety miles from Taiwan. That makes the Philippines one of the United States’ closest allies geographically. If China decides to attack Taiwan, analysts expect the United States to rely on military bases in the Philippines as part of its response.

The outcome of the 2024 election could help or harm U.S. partnerships in the Pacific. Taiwan is just one example. The country relies on U.S. military support in the region to deter Chinese aggression. But Democratic and Republican leaders disagree on how much support the United States should give its Pacific allies—including Japan, the Philippines, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Republican candidate Donald Trump has been openly critical about those Pacific partners, demanding that they pay more for U.S. military support. Many of those countries, including Japan and the Philippines, are already working on security agreements in case Trump is reelected—fearing he could withdraw support. Trump has not made any decisive statement about Taiwan. Recently, he declined to say whether he would commit the United States to defending Taiwan against Chinese aggression.

President Joe Biden has been more openly supportive of security agreements. Throughout 2024, the Biden administration has worked to deepen its security partnership with Japan and South Korea. Biden has also said multiple times that the United States will defend Taiwan if China attacks it.

As in 1900, the 2024 election may determine U.S. involvement in the Pacific. If Democratic nominee Vice President Kamala Harris follows Biden's lead, voters will be faced with presidential candidates presenting different approaches to those issues. This November, U.S. military and economic strategy in the Pacific could once again be on the ballot.