Modern History and U.S. Foreign Policy: Asia

Asia is the world’s largest continent, covering about 30 percent of the earth’s total landmass. It also has large, diverse populations, each with its own history and culture.

East Asia is home to some of the world’s oldest civilizations. Chinese history stretches back more than four thousand years, and its early empires—some of the wealthiest in history—invented paper, movable type (in printing), gunpowder, and the compass. Korea and Japan, similarly, trace their histories back to dynasties across thousands of years that shaped the language and culture of their modern-day countries.

Many of the countries that make up South and Central Asia are quite young: Pakistan and India became independent countries following the end of British colonial rule in 1947, Bangladesh followed in 1971, and Kazakhstan and its neighbors emerged as independent countries after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. However, this part of the world does not lack history. The Indus Valley Civilization in what is now northeast Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwest India was an early cradle of civilization, and the region is one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in the world. Hinduism, the world’s third-largest and possibly oldest living religion, traces its origins to near modern-day Pakistan; India and Nepal gave birth to Buddhism; and Islam arrived in the region during the seventh and eighth centuries.

The ancient Silk Road connected the entire region, passing from East Asia to South and Central Asia. Several empires ruled large portions of this part of the world for centuries. But by the end of the nineteenth century, most of the region was under European colonial rule, with the British controlling a majority of South Asia, and the Russian Empire occupying large areas of Central Asia. This relationship to colonialism—and the subsequent disentanglement from it—set the stage for much of the region’s modern history.

That modern history also features the arrival of a new world power: the United States.

A Pacific power itself, the United States has maintained an interest in Asia for more than a century. World War II, however, established the United States as the preeminent military power in the Pacific.

But U.S. influence has not grown unopposed. Throughout the Cold War, the Soviet Union fought to expand its influence throughout the region, drawing the United States into several large-scale proxy conflicts from Korea to Vietnam. More recently, an unpredictable, nuclear-armed regime in North Korea threatens the region. But the biggest foreign policy questions for the region and for the United States’ role in it concern China’s growing power and how the United States will seek to respond to it.

Here are some of the most important moments in the history of the region—and of U.S. foreign policy toward it—that have shaped events in Asia for over a century.

1644 - 1911

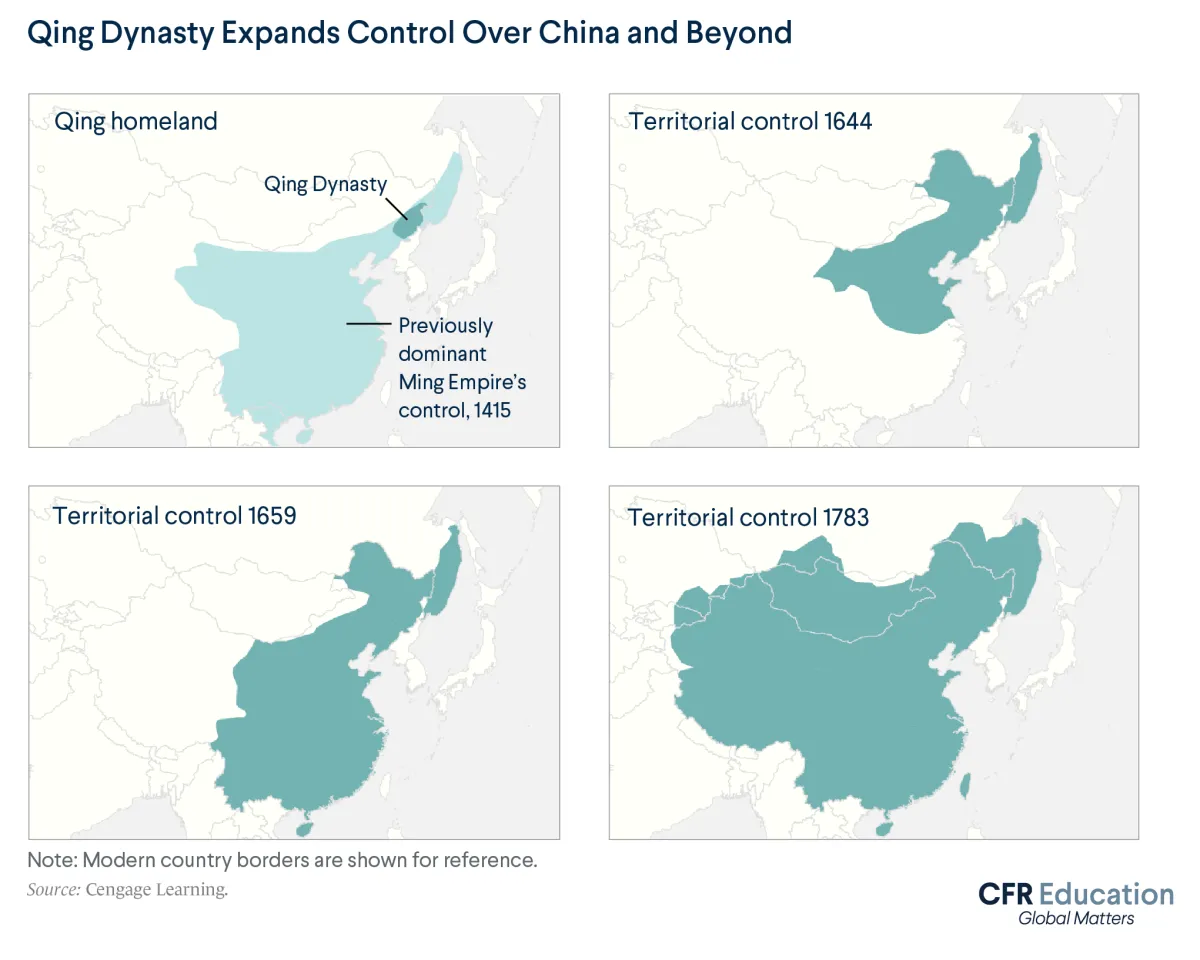

China’s Last Imperial Dynasty

At its peak, the Qing Empire was one of the largest in the world—and the largest in Chinese history. It covered territory that now includes not only China, but also Mongolia and parts of Russia. Throughout the nineteenth century, however, the Qing Empire faced several destabilizing events. These included wars against foreign powers, like the British (the Opium Wars) and the Japanese (Sino-Japanese War), which led to the loss of territory as well as economic concessions. A devastating fourteen-year-long civil war (the Taiping Rebellion), one of the deadliest civil wars in human history, further weakened Qing control. While the Qing attempted political reform, a series of reformist and revolutionary movements called for a new government. These movements were motivated not only by frustration with the Qing government, but also a growing wave of nationalism, which argued Chinese identity should be based not on region or bloodline, but on shared culture. After nationwide uprisings in late 1911, during which many provinces declared independence, the Qing empire finally fell from power. The 1911 revolution set the stage for a new China, one with a strong national identity and global ambitions.

1796

Dutch Trade Leads to Colonization in the East Indies, Southeast Asia

The spice trade between Asia and Europe dates back to ancient times. By the sixteenth century—after explorers opened new maritime trade routes—European powers began competing for control over these lucrative markets. The Netherlands emerged as an early power. The Dutch Republic established the Dutch East India Company (1602-1796), which would become the largest early modern trading company. The company’s charter gave it the power to make treaties with Asian rulers and create its own colonies. It also maintained a private army to facilitate its operations, often through brutal acts of violence. In Indonesia, for example, attempts to monopolize the spice trade led the company to massacre local populations and import slaves from West Africa for labor. Colonization continued throughout the nineteenth century, as the Dutch expanded across Indonesia (then named the Dutch East Indies). Elsewhere in the subregion, England established colonies in modern-day Malaysia. Meanwhile, France colonized Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, which became part of French Indochina in 1887. Colonial rule changed populations and economies. In Malaysia and Cambodia, local peoples were marginalized in favor of immigrant labor. In Burma (now Myanmar), the British encouraged Indian and Chinese immigration, planting the seeds for future political divisions.

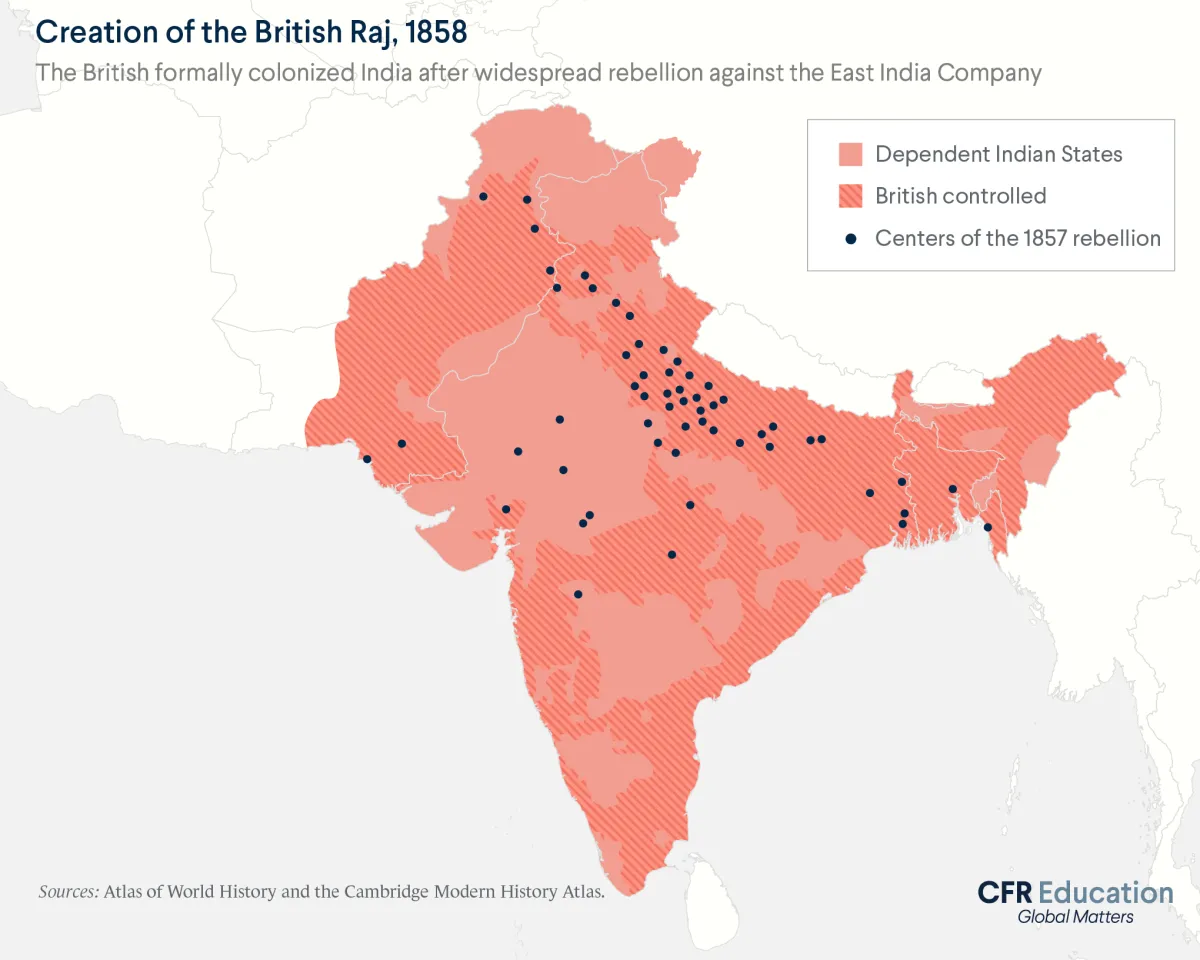

1858

British Trade Leads to Colonization on the Indian Subcontinent

By the 1500s, Europeans were trading directly with the Indian subcontinent. Textiles and spices were the region’s prized commodities, and in 1600, Queen Elizabeth I approved the establishment of the East India Company, granting a few hundred merchants a monopoly on British trade with the subcontinent. Initially, the company operated from small trading outposts along the coast of modern-day India. But in its quest for profit, the company amassed a giant private army—twice the size of the British army. It exploited the weakness of the Mughal Empire, which was in decline. Soon, the company took over as a colonial ruler in India. At its peak, the company ruled over two hundred million people. But the company was not popular. Those under its rule objected to the company’s high taxes and interference with traditional Muslim inheritance laws. Tensions peaked in 1857, when Indian soldiers accused the British of supplying rifle cartridges greased with beef and pork fat, an insult to Hindus and Muslims. Indian soldiers and citizens rebelled, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Indians and thousands of British. In response, the British dissolved the East India Company and instituted direct rule, thus beginning the British Raj in 1858. Over time, the British would expand the colony, exploiting tensions between Hindu and Muslim populations.

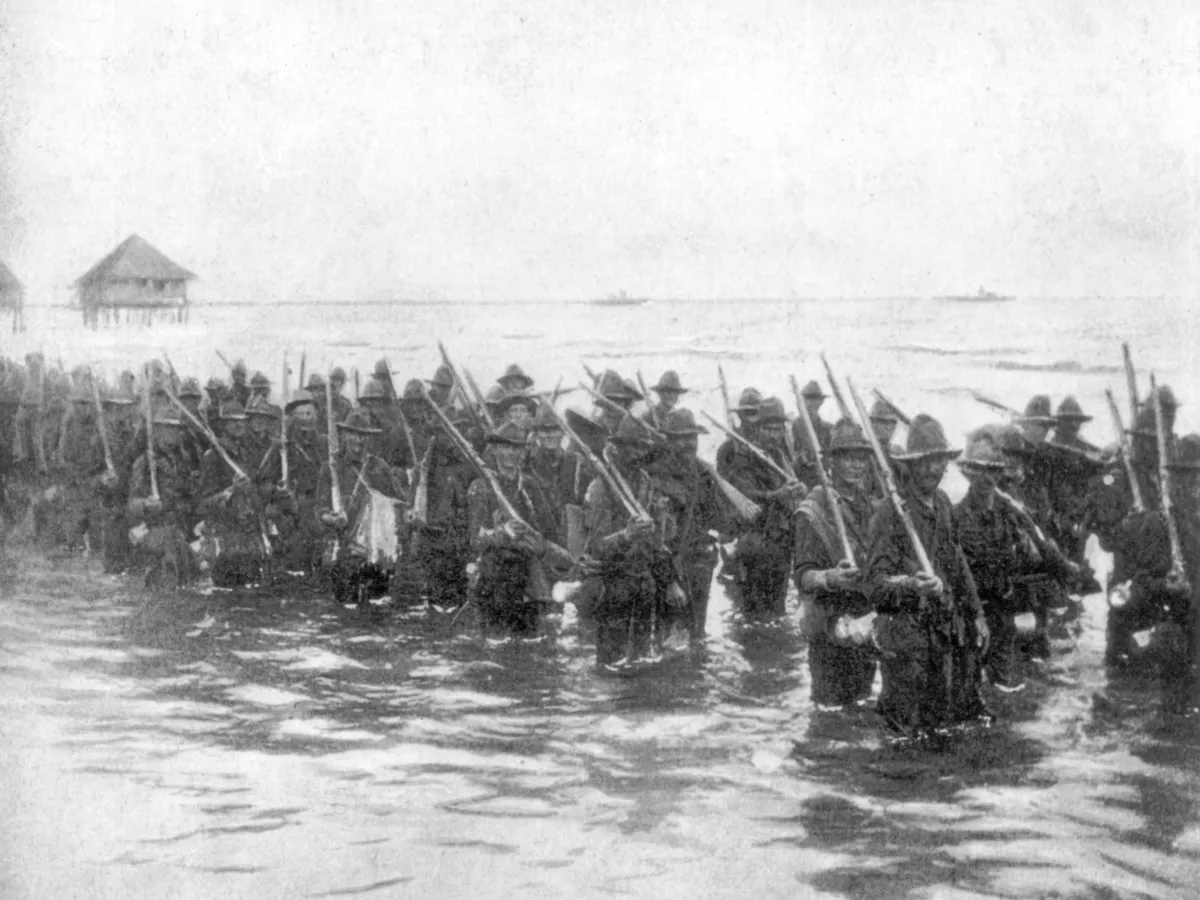

1898

The United States Becomes a Pacific Power

Prior to the late nineteenth century, the United States was largely a regional, rather than global, power. It exerted its influence throughout the Americas, but refrained from creating colonies overseas, as many European powers did. But as the United States grew both militarily and economically, it sought not only to consolidate its power in the Western Hemisphere but also to pursue trade opportunities with Asia. It saw Spain, with Asian and American colonies, as a power in decline, and in 1898 the two countries went to war. After just a few months of fighting, the Spanish conceded defeat and transferred control of their Caribbean and Pacific colonies—namely Guam and the Philippines—to the United States. The war inaugurated the United States as an overseas imperial power and established it as a permanent political and military influence in the Pacific.

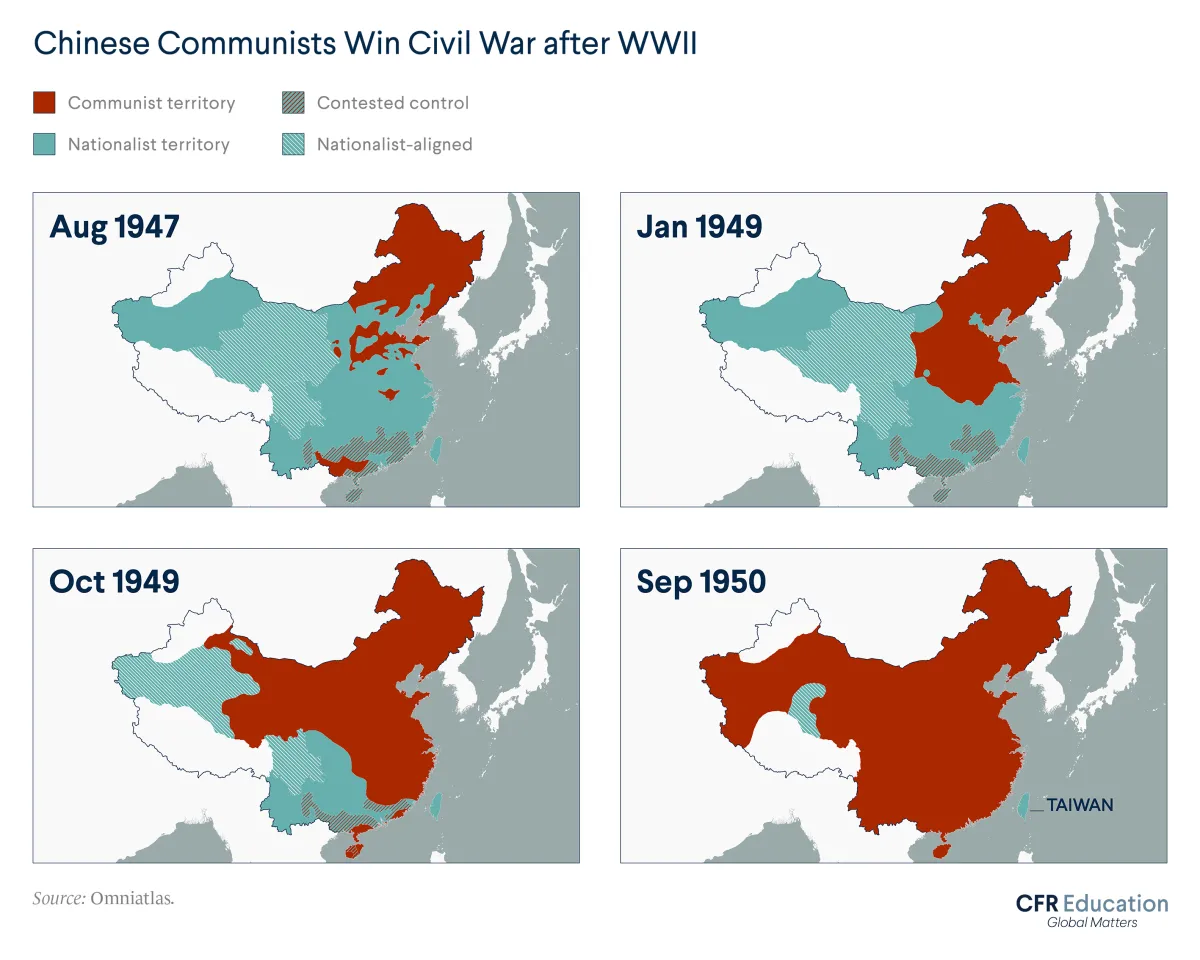

1912-1949

Chinese Civil War Concludes With Communist Victory

In 1912, dynastic rule ended in China. The Republic of China, headed by the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, or KMT), replaced the Qing dynasty. Led by Chiang Kai-shek, the KMT oversaw an authoritarian government and sought to stitch together a country that had fractured into territories run by warlords. Soon, however, it had to contend with a challenge from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), led by Mao Zedong. Mao sought to lead a workers’ revolution and establish a communist government. A brutal civil war ensued, dividing China from 1927 to 1949. After more than twenty years of fighting and millions of deaths, the CCP emerged victorious. On October 1, 1949, Mao declared the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, which the Communist Party rules to this day. The KMT fled to the island of Taiwan. Now, a deep political rift remains as mainland China views Taiwan as a renegade province that must be brought under its control.

1937-1945

World War II Ends Japanese Empire, Introduces Nuclear Age

In 1942, after decades of imperial expansion, the Japanese Empire ruled over two hundred million people across thirteen modern-day countries, and it did so through extraordinary violence. The empire conscripted over one million Koreans as enslaved labor and forced hundreds of thousands of girls and women into sexual slavery. In one of the region’s darkest chapters known as the Nanjing Massacre, between 1937 and 1938 Japanese soldiers killed up to two hundred thousand people and raped tens of thousands of women in China. On December 7, 1941, Japanese forces attacked the United States at Pearl Harbor, bringing the United States into World War II. Over the following four years, the massive numbers of U.S. troops, ships, and arms sent to the region built the infrastructure for the United States to become the preeminent military power in the Pacific for decades to come. The war culminated with the detonation of the first nuclear weapons on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Though exact numbers are unknown, some historians estimate that 140,000 people in Hiroshima and 70,000 people in Nagasaki died immediately. Thousands more lost their lives in subsequent years from birth defects and cancers caused by the nuclear fallout. The use of nuclear weapons (the only times they have been used in war) ushered the world into a new era, one in which countries that possessed nuclear capabilities wielded unprecedented power.

1945 - 2002

Southeast Asian Colonies Fight for Independence

By the twentieth century, most of Southeast Asia was under the control of British, Dutch, French, and American powers. During World War II, the Japanese Empire occupied the region—taking control over former European colonial territories including Burma (Myanmar), Malaya (Malaysia), the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). When the war ended, European countries regained their colonies. Violence began almost immediately. In 1945, Vietnam declared independence from France, and Indonesia declared independence from the Netherlands. Dutch forces, believing most people favored colonial rule, sought to “cleanse” areas of rebellion. After four years of insurgency—and under considerable international pressure—the Dutch granted independence to Indonesia in 1949. The fight for Vietnam would be even longer and bloodier. Following calls for independence, the French military took over southern Vietnam and soon after attacked the country’s north. The resulting Indochina War saw French forces (backed by the United States) battle Vietnamese forces (backed by China). Vietnam would continue to be occupied by foreign powers into the 1970s. Other countries gained independence directly after World War II, like the Philippines (1946). Some—including Laos and Malaysia—achieved limited self-government before gaining independence. East Timor became the final country in the region to gain independence in 2002.

1947

India Gains Independence, Pakistan Is Founded

In 1946, the British government announced it would leave India, granting the subcontinent’s independence from colonial rule. Indians of all faiths—led by activists like Mahatma Gandhi—had long protested for their freedom. Meanwhile, a small group known as the Muslim League, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, worried about becoming a vulnerable minority in a majority-Hindu India. The group proposed that the British should grant autonomy to a Muslim state known as Pakistan. Although the proposal was largely meant as a bargaining chip to secure Muslims’ rights in India, the British accepted this proposal. When they departed the subcontinent, they divided it into two newly independent countries. On August 14, 1947, Pakistan was born. One day later, India celebrated its independence. What followed is known as the Partition of India, a deeply painful period in the region’s history in which India and Pakistan defined their boundaries. Millions of Muslims migrated to the newly created Pakistan and millions of Hindus and Sikhs fled to India. The partition was marked by violence; killing, arson, abductions, and sexual violence were widespread. At least ten million Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs became refugees, and at least five hundred thousand people across the subcontinent died in the violence. Since the trauma of partition, Indians and Pakistanis have maintained a deep mistrust of each other, and fought in three major wars.

1949

China’s ‘Century of Humiliation’ Drives Global Ambition

When Mao Zedong emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil War, one of his first actions was to declare an end to his country’s “century of humiliation.” For the previous one hundred years, foreign powers—the British, French, Germans, and Japanese—had exploited the once-great Chinese empire. Mao pledged that China would never again be taken advantage of by foreign powers. (Successive Chinese leaders have used this painful chapter to justify the CCP’s monopoly on political power, arguing that a weak and internally divided China invites foreign aggression.) When Mao took power in 1949, one foreign power—the United States—quickly established several neighboring alliances. The United States allied with Japan (1951), Australia (1951), the Philippines (1951), South Korea (1953), Taiwan (1954), and Thailand (1954) in what was dubbed the hub-and-spoke system. These bilateral agreements meant that if an allied country were attacked, the United States would be obligated to come to its defense. Although the United States walked back its mutual defense treaty with Taiwan in 1979, it has maintained its other alliances to this day.

1950-1953

Korean War Leaves Peninsula Divided

When the Japanese Empire surrendered its colonial territories at the end of World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union divided the Korean peninsula—forming a communist government in the north and a capitalist one in the south. This separation was intended to be temporary, but in 1950 North Korea (with Soviet and Chinese backing) invaded the south, starting the Korean War. Fearing a communist takeover of the entire peninsula, the United States led a UN coalition to defend South Korea. After three years of fighting in which millions died, the two sides laid down their arms—but the peninsula remained divided. The United States stayed, even after the fighting. Today, South Korea is home to the largest U.S. overseas military base, hosting nearly thirty thousand U.S. troops. Given that North and South Korea are still technically at war, these troops continue to protect South Korea, a U.S. ally, from potential threats.

1954

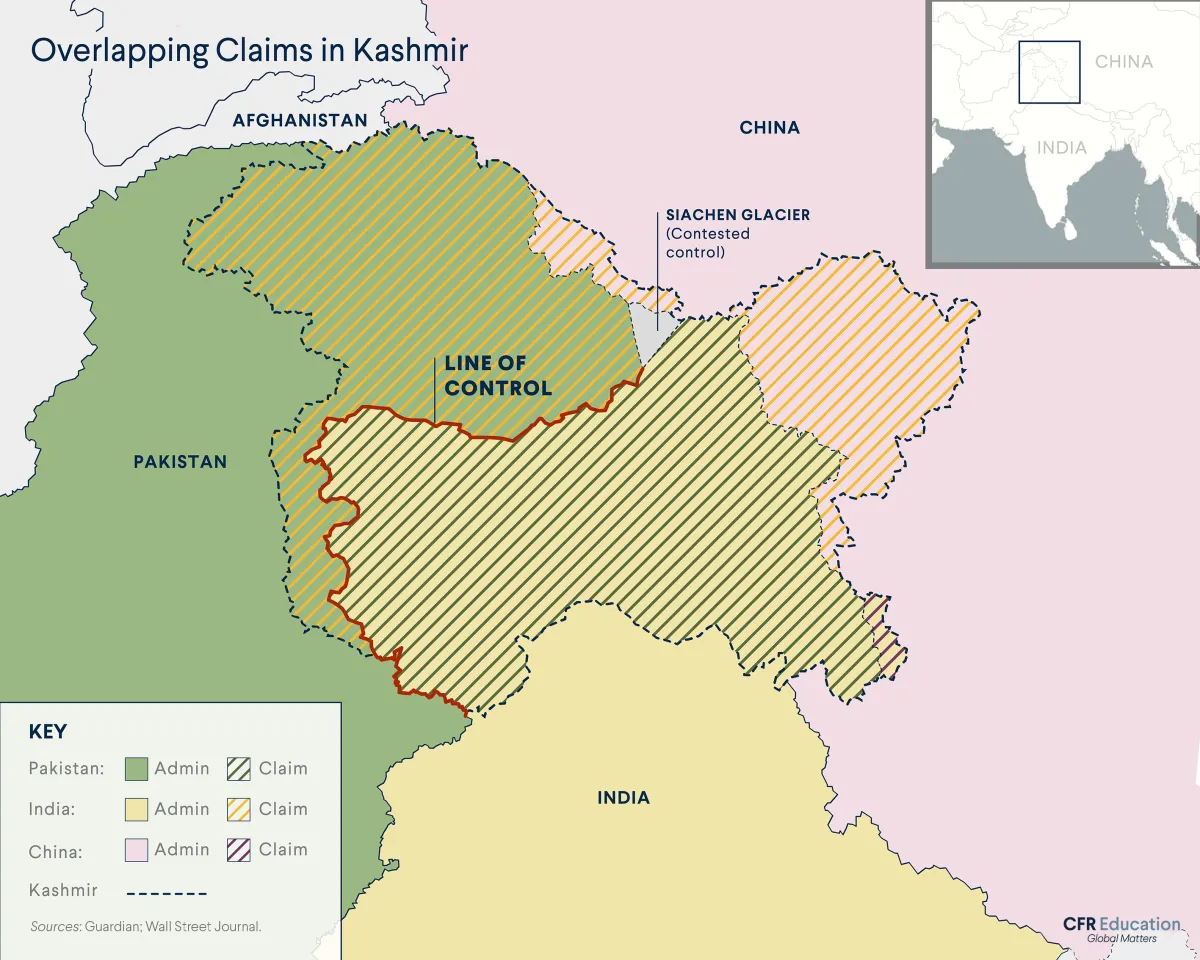

Kashmir Becomes South Asia’s Most Contested Region

When the British partitioned the Indian subcontinent, hundreds of semi-independent kingdoms outside direct colonial administration had to choose between joining India or Pakistan. The decision was typically straightforward and fell along religious and geographic lines: Hindu-majority states joined India, while Muslim-majority states opted for Pakistan. But Kashmir, the largest of these territories, was in a tricky spot. It had a Muslim-majority population but a Hindu ruler. Initially, the ruler of Kashmir decided to stay independent. But tribesmen from Pakistan invaded Kashmir in an attempt to force it to join Pakistan. In response, the Kashmiri monarch signed a deal: Kashmir would join India—and enjoy significant autonomy—in exchange for protection. Pakistan rejected this decision, and just months after independence, India and Pakistan went to war over Kashmir. By the end of the yearlong war, India controlled two-thirds of Kashmir and Pakistan had the rest. To this day, that cease-fire line (called the Line of Control) divides Kashmir, with India and Pakistan administering their side of the boundary. China also controls part of the region.

1954 -1974

Domino Theory Influences U.S. Involvement in Vietnam

When U.S. policymakers looked at a world map in the 1950s and 1960s, one area made them concerned: Southeast Asia. Mao Zedong’s Communist government had just taken over China, and U.S. policymakers feared that neighboring countries would follow suit, falling one by one to communism. This so-called domino theory contributed in large part to the U.S. decision to send troops to Vietnam, where Soviet-backed guerrillas in the country’s north fought U.S.-backed government forces in the south. The war ultimately involved some three million U.S. troops, caused just as many deaths (though mostly of Vietnamese civilians), and ended in a communist victory. In the United States, the largely unpopular war caused civil unrest and eroded the public’s trust in the government. Meanwhile, as policymakers feared, coinciding civil wars also brought communist governments to power in neighboring Laos and Cambodia. In Cambodia, Pol Pot then perpetrated a genocide against millions of Cambodians, including most of the country’s Buddhist monks and ethnic minorities from 1975 to 1979. This time, the United States did not intervene.

1971

Bangladesh Becomes Independent and Nuclear Tensions Grow

Upon independence, Pakistan consisted of two wings—East and West Pakistan—separated by 1,300 miles of Indian territory. West Pakistan, where the government was based, was much more powerful and denied East Pakistan various economic, linguistic, cultural, and political rights. After decades of mounting resentment against West Pakistan’s domination, East Pakistanis intensified independence protests in 1971. In response, troops from West Pakistan occupied the area to prevent it from seceding. Troops then committed genocide against their own citizens, killing up to three million people. India intervened on behalf of East Pakistanis and ultimately pushed West Pakistani troops out of the area. East Pakistan was then renamed and an independent Bangladesh was born. Pakistan’s territorial loss was devastating for the country and seemingly confirmed its suspicion that India was an existential threat. Pakistan soon began developing nuclear weapons to defend itself against India. Thus began the nuclear race in South Asia: when India conducted its first nuclear test in 1974, Pakistan accelerated its own program, and both countries had publicly acquired the bomb by 1998. While the United States worked to dissuade both countries, ultimately it was unable to prevent India or Pakistan from becoming nuclear powers.

1972

Nixon Redefines U.S.-China Relations

After the Chinese Civil War, the United States refused to recognize Mao Zedong’s Communist government. Instead, Washington cooperated with the newly exiled government in Taiwan, a strong anti-communist ally. But in 1972, Richard Nixon shocked the world by becoming the first sitting U.S. president to visit mainland China, in an effort to establish relations between the two countries. Nixon, one of the most prominent anti-communist politicians of the Cold War, suddenly warmed up to Mao’s China for several reasons. First, Nixon hoped to split China from the Soviet Union, another communist country—and, therefore, weaken the Soviet Union’s position in the world. Second, in the midst of the Vietnam War, Nixon sought to isolate North Vietnam from its patron, China. And finally, Nixon believed that working with China was necessary to prevent it from threatening its neighbors. Ultimately, the United States formally recognized Beijing (and cut ties with Taiwan) in 1979 under President Jimmy Carter, ushering in an era of cooperation between the two countries.

1979

Soviet-Afghan War Draws the United States into Region

Over the past two hundred years, many countries have tried and failed to conquer Afghanistan, a country at the strategic intersection of India, China, and the Middle East. Its epithet, “the graveyard of empires,” gives a sense of how invasions have gone. In 1979, the Soviet Union learned this lesson when it sent troops to support Afghanistan’s unpopular communist government against anticommunist Muslim insurgency groups. Collectively known as the mujahideen, these groups received support from many foreign governments, including the United States. The mujahideen succeeded, pushing the Soviets out of Afghanistan. But the war left an estimated one million civilians dead—and created a power vacuum. That vacuum was eventually filled by the Taliban, an Islamic fundamentalist group with roots in the mujahideen movement. The group would govern most of the country and impose a strict interpretation of Islamic law—banning television and musical instruments and outlawing education for women. They would kill thousands of civilians and burn entire villages. They would also provide support to a young leader of a new Islamist movement, Osama bin Laden.

1989

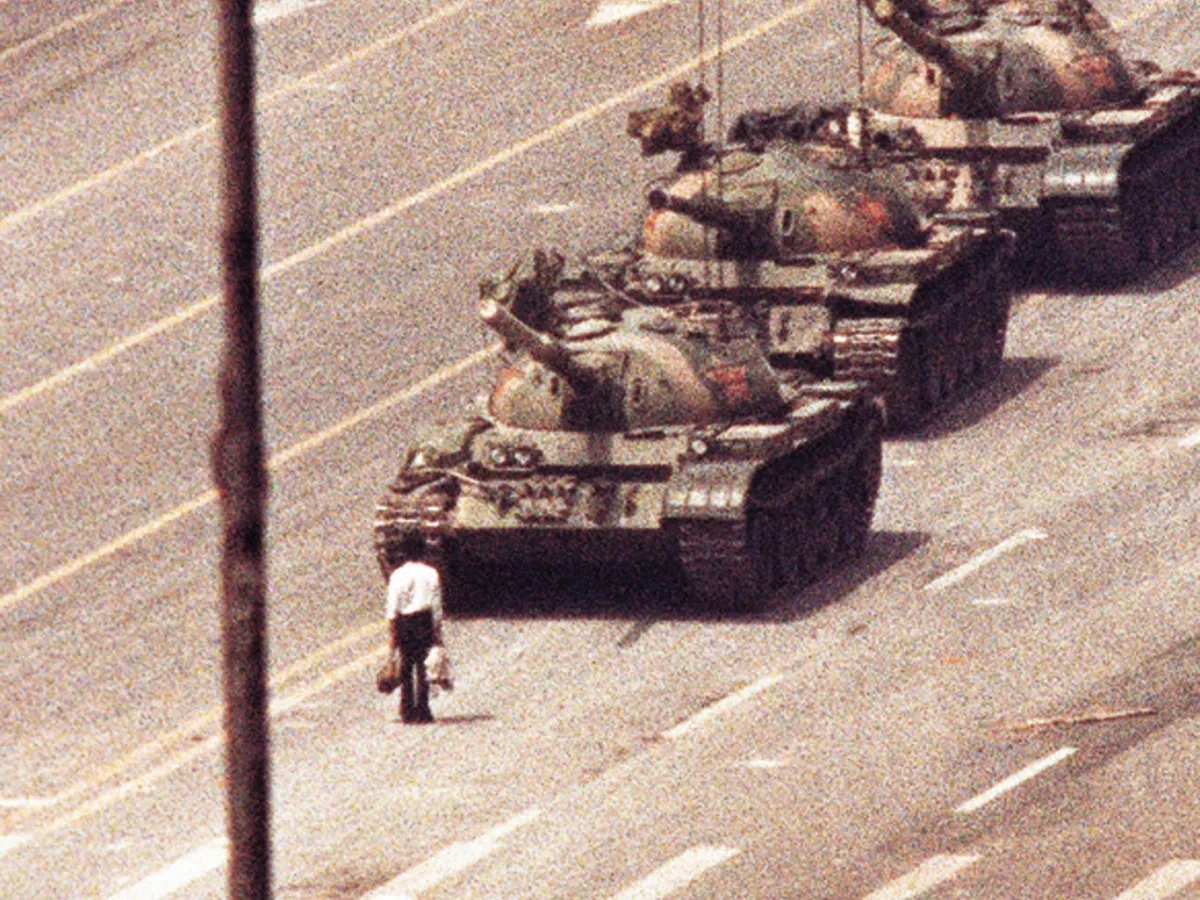

Tiananmen Square Massacre Demonstrates China’s Intolerance of Dissent

In the 1980s, hundreds of millions of people in China escaped extreme poverty owing to the country’s economic reforms. Nevertheless, vast inequality, rising food prices, and government corruption remained intractable. These concerns boiled over in May 1989 when students across China poured out into the streets demanding freedom of speech, democratic reforms, and an end to corruption among Communist Party elites. After negotiations with protesters failed, the government declared martial law and sent hundreds of thousands of troops to Beijing, where nearly one million students were demonstrating in the iconic Tiananmen Square. When protesters refused to leave, the government opened fire, killing hundreds—if not thousands—of civilians in the square and surrounding streets. The message from the Communist Party to the people was clear: political dissent would not be tolerated. The massacre remains one of the country’s most politically sensitive and censored events. All web searches originating in China that have to do with the incident are blocked, and many young Chinese people are unaware it ever happened.

1991

Soviet Collapse Destabilizes Central Asia

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan became independent countries facing enormous economic challenges: how to untangle their economies from the Russian economy, how to deal with soaring inflation, and how to exist without Soviet aid. These countries, therefore, saw a slow transition to market economies. In the absence of Soviet control, the United States sought to expand its influence. Three priorities shaped the U.S. foreign policy agenda in the region: security, democracy, and energy. In pursuit of its first priority, the U.S. government paid Kazakhstan to seal nuclear reactors, remove uranium from nuclear plants, and transfer leftover Soviet nuclear weapons back to Russia to ensure that they did not fall into the wrong hands. Second, the United States promoted democracy and independence by sending billions of dollars of foreign aid. And finally, the United States promoted investment and construction in the region’s oil and gas industries. Despite these efforts, Central Asian countries today remain largely within the sphere of influence of their closest ally, Russia, which continues to serve as a major trading partner and weapons provider.

1997

Taiwan and Hong Kong Test Chinese Relations With the West

The British, who ruled Hong Kong since the 1800s, returned the colony to China in 1997. Fearing China’s government would revoke democratic freedoms that Hong Kongers had long enjoyed—including freedoms of speech and assembly—Britain struck a deal with Beijing. Hong Kong would officially rejoin China, but for fifty years the city would have its own constitution and significant autonomy before being fully reintegrated into China in 2047. This setup was called “one country, two systems.” (However, just two decades into this policy’s implementation, Beijing is already limiting the freedoms and autonomy guaranteed to Hong Kongers—moves the United States has denounced, but done little to discourage.) Hong Kong is not the only point of tension for China. Beijing also hopes to eventually reunify Taiwan with the mainland through a similar arrangement. In 1979, as the United States grew closer to China, it severed formal ties with Taiwan. Despite moving closer to China, the United States underscored that it still had unique commitments to Taiwan. However, the United States has never clarified whether the United States would actually come to Taiwan’s defense if it were attacked. This ambiguity was an intentional effort to deter Chinese aggression while avoiding confrontation. For decades, a tense status quo held. But recently, things are looking less stable. Some experts project that Taiwan could eventually declare formal independence, an unacceptable outcome for China.

2001

China Joins the WTO, But Shirks Reform

For decades, China was the world’s only large economy that was not a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO), an institution that sets international trade rules. The United States strongly encouraged China to join, both to provide American exporters increased access to a billion-person market and in hopes that WTO membership would make China a more open society. When China finally joined in 2001, U.S. manufacturers did gain access to China’s enormous market. But hopes for Chinese reforms quickly faded. The Chinese Communist Party used the country’s rapid economic growth to further legitimize and solidify its hold on power. It expanded censorship and surveillance systems and increased repression of minorities and government critics. China’s economic emergence raised the question of whether it would adopt the political norms of Western countries, or whether it would seek to reshape the world in its own image. China’s actions since joining the WTO imply the latter. Given this outcome, U.S. policymakers continue to question the extent to which it is possible to work with China in a mutually constructive way.

2001 - 2021

Afghanistan – The Longest War in U.S. History

On September 11, 2001, nineteen members of the terrorist group al-Qaeda attacked the United States. In response, President George W. Bush gathered a coalition of countries to invade Afghanistan, where the ruling Taliban government provided refuge to the organizers of those attacks. In a matter of weeks, the coalition successfully removed the Taliban from power. But those gains were short-lived. Within a few years, the Taliban returned and waged an insurgency against the newly installed Afghan government and the U.S. troops supporting it. Nearly two decades after the invasion, the Taliban had regained control over much of the country, the United States had spent about $1 trillion and lost more than 2,000 soldiers. With public weariness over the ongoing war mounting, the United States decided to withdraw from the country, despite fears that doing so could lead to the collapse of the Afghan government. In August 2021, the final U.S. troops left the country. During the withdrawal, the Taliban quickly retook territory across the country, entering the capital, Kabul, on August 15. Since then, the Taliban have rolled back many of the country’s reforms. Women and girls are now barred from both secondary and higher education—part of some of the most gender discriminatory policies in the world.

2013

China Launches Its Belt and Road Initiative

Under the leadership of Xi Jinping, China has increasingly sought to assert that strength around the world. In 2013, Xi announced one of the CCP’s most ambitious projects to achieve this goal—the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The initiative has two components: an overland trade route (the “belt") and a maritime trade network (the “road”). The belt connects Asia to Europe through a network of highways, railways, and energy pipelines. The road connects China to Southeast Asia, Africa, and Europe by way of maritime ports. China had many reasons for pursuing the BRI: it wanted more secure trade routes that didn’t pass through U.S. allies; it wanted to stimulate its economy and give Chinese companies more foreign contracts; and it wanted to extend its influence through economic partnerships with other countries. More than 140 countries are part of the BRI network. While the BRI has provided billions of dollars of funding for countries to develop the infrastructure needed to connect with the initiative, it has also been criticized for trapping those countries in debt as a way of increasing Beijing’s leverage.

2018

United States Grows Closer to India, Further From Pakistan

During the U.S. War in Afghanistan, Pakistan served as a strategic base for U.S. and allied forces, in exchange for U.S. military aid. But despite Pakistan being labeled a major non-NATO ally, the U.S.-Pakistan alliance has followed a rocky trajectory. Many U.S. politicians have argued that Pakistan is either unwilling or unable to tackle terrorist activity within its borders. This perception led the United States to cut almost one billion dollars in security assistance in 2018, throwing the future of the alliance into question. Meanwhile, U.S.-India relations have warmed over the years. India’s economic reforms throughout the 1990s sparked an economic boom, and its strong IT and banking sectors made it an increasingly valuable economic partner for the United States. Since then, trade between the United States and India has grown from $19 billion in 2000 to $143 billion in 2019. There have been other areas for cooperation, like concerns about Islamic extremism. In 2008, a Pakistan-based terrorist group carried out an attack in Mumbai, killing 164 people and further straining diplomatic ties between India and Pakistan. The United States and India have also found common ground in moderating China’s increasing presence in South and East Asia.

2020

COVID-19 Spreads From Wuhan

In December 2019, patients at a hospital in Wuhan, China, began to experience pneumonia-like symptoms. This illness, later identified as a new coronavirus, eventually spread across Asia and then the world—reaching nearly every country and causing the death of over 7 million people. Countries in East Asia and the Pacific were hit especially hard. Sales and employment plummeted in those regions. The number of people in East Asia living below the poverty line was projected to have increased by roughly thirty-eight million as a result of the initial economic shock. The pandemic also hurt China’s global influence. China faced widespread criticism of its initial response to the virus. Journalists, diplomats, and world leaders said China’s arrest of doctors who spoke openly about the disease and the government’s weeks-long delay in warning the general public amounted to a deliberate political cover-up to protect the country’s stable and authoritative image. The pandemic hurt Chinese influence in the region in other ways as well. It forced China to abandon or delay infrastructure projects under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). It also put economic stress on countries hosting Chinese development projects, prompting some to reconsider their involvement with the BRI. In the years following the pandemic, Chinese lending under the BRI has continued to slow, with some analysts highlighting COVID-19 as a major factor in the decline.

2020 - Present

Tensions Grow Between Regional Powers and Partners

Even before COVID-19, tensions had been growing between China and its neighbors. One area of dispute continues to be activity in the South China Sea. Roughly one third of global maritime trade relies on this route—making it both valuable and important. The ten Asian countries that border the South China Sea have overlapping claims to the sea’s various zones. Island construction, military patrols, and fishing activity have all increased tensions between those countries. These activities have also increased tension with the United States, whose Pacific allies border the sea. Other points of regional friction involve military activity—including nuclear tests in North Korea and Chinese military drills around Taiwan. That activity has also strained relations between China and the United States. However, the most direct confrontation between both countries has been economic. In 2018, President Donald Trump—after accusing China of unfair trade practices—imposed tariffs on Chinese goods, prompting a trade war as China retaliated. Tariffs continued through the Joe Biden administration. During his second term, Trump doubled tariffs on some Chinese goods, marking a new escalation in trade tensions. The trade war has already resulted in billions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of jobs lost for both countries. It has also prompted many countries to restructure their own supply chains and economic strategies. As tensions continue, the long-term outcome of this ongoing trade war remains uncertain for the region.