The 1880 Garfield vs. Hancock Election and Immigration Today

A forged letter on the eve of the election ignited riots over immigration, using rhetoric still common now.

Setting the Scene

Imagine you are there: It is Halloween, 1880. You are in Denver, Colorado. The presidential election is two days away, and tensions are high. The talk of the town is a letter, published just over a week ago in a Democratic newspaper and distributed across the country. It’s been pasted on store windows across the Western states.

The letter is supposedly written by Republican candidate James Garfield. The topic is “the Chinese question.”

Since 1849, Chinese immigrants have been making their way to the United States, first to mine gold and then to work the railroads. Most are young men and boys. They are paid only pennies each day. Such cheap labor has inspired fears that Chinese immigrants will replace unskilled white workers, especially in Western states like California, Nevada, and Colorado. Denver now has hundreds of Chinese residents. Although many work as laundrymen in roles not currently taken by white workers, anti-Chinese sentiment is growing. Some white residents fear jobs will be taken from Americans.

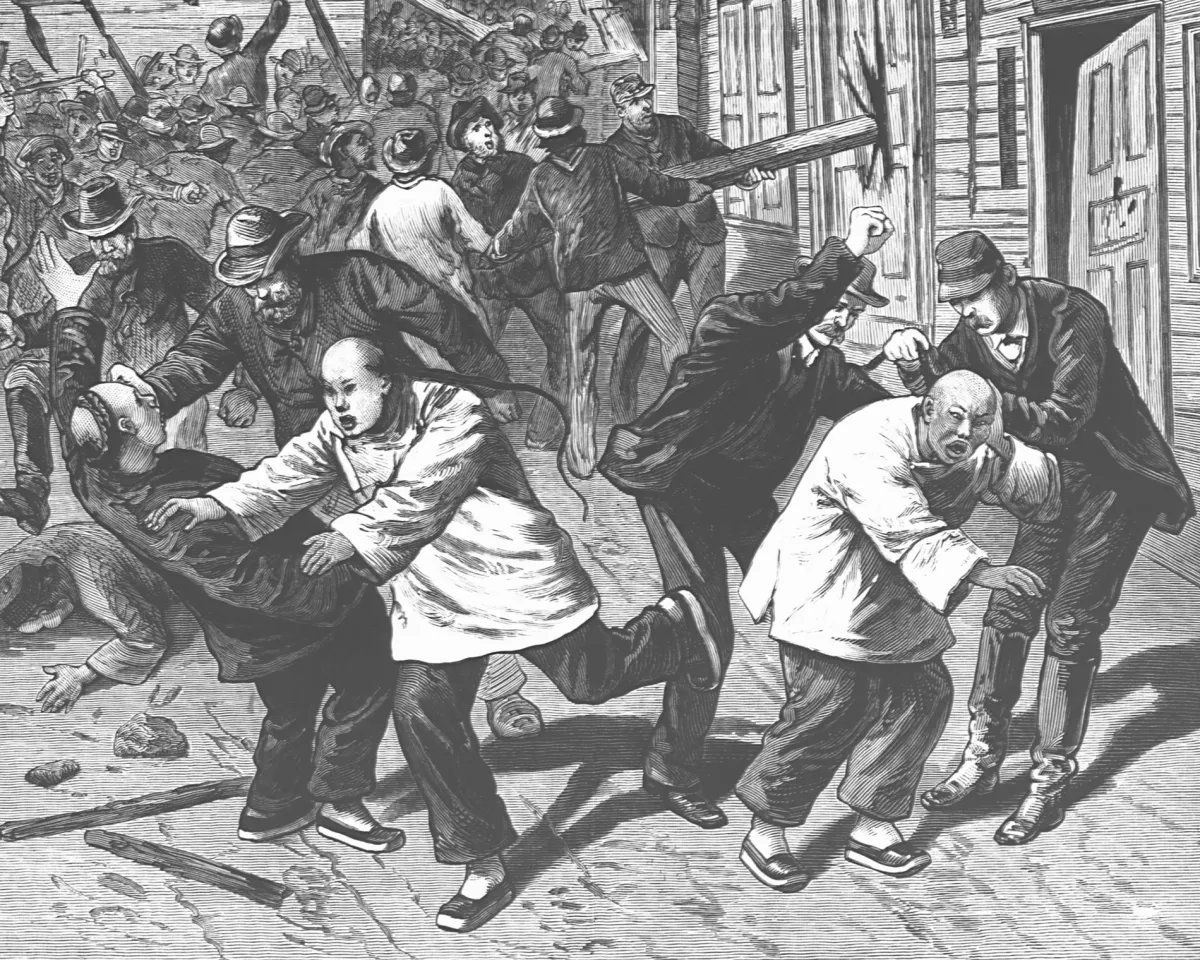

Now, Garfield’s printed letter—which supports Chinese immigration—is making things worse. Many voters across the Western states are furious with the presidential candidate. All week, the newspapers have been fanning the flames, calling Chinese immigration an invasion—and the main campaign issue in Colorado. In Denver today, on Halloween, a riot begins.

It starts in the morning outside a saloon, when a white man, unprovoked, strikes a Chinese man. By 2:00 p.m., thousands have gathered in Denver’s Chinatown. Some chant, “Garfield’s a Chinaman,” using a then-common racial slur. The mob begins to loot Chinese homes and target Chinese laundromats and assault Chinese men. The Denver fire department sprays the crowd with hoses. The crowd responds by throwing bricks. In the red-light district, sex workers protect Chinese men by brandishing stove pokers, champagne bottles, and a shotgun at the mob. At the end of the riot, nearly every Chinese home is destroyed. One Chinese man, Look Young, has been killed.

In this frenzied climate, Americans head to the polls.

The 1880 Election: Garfield vs. Hancock

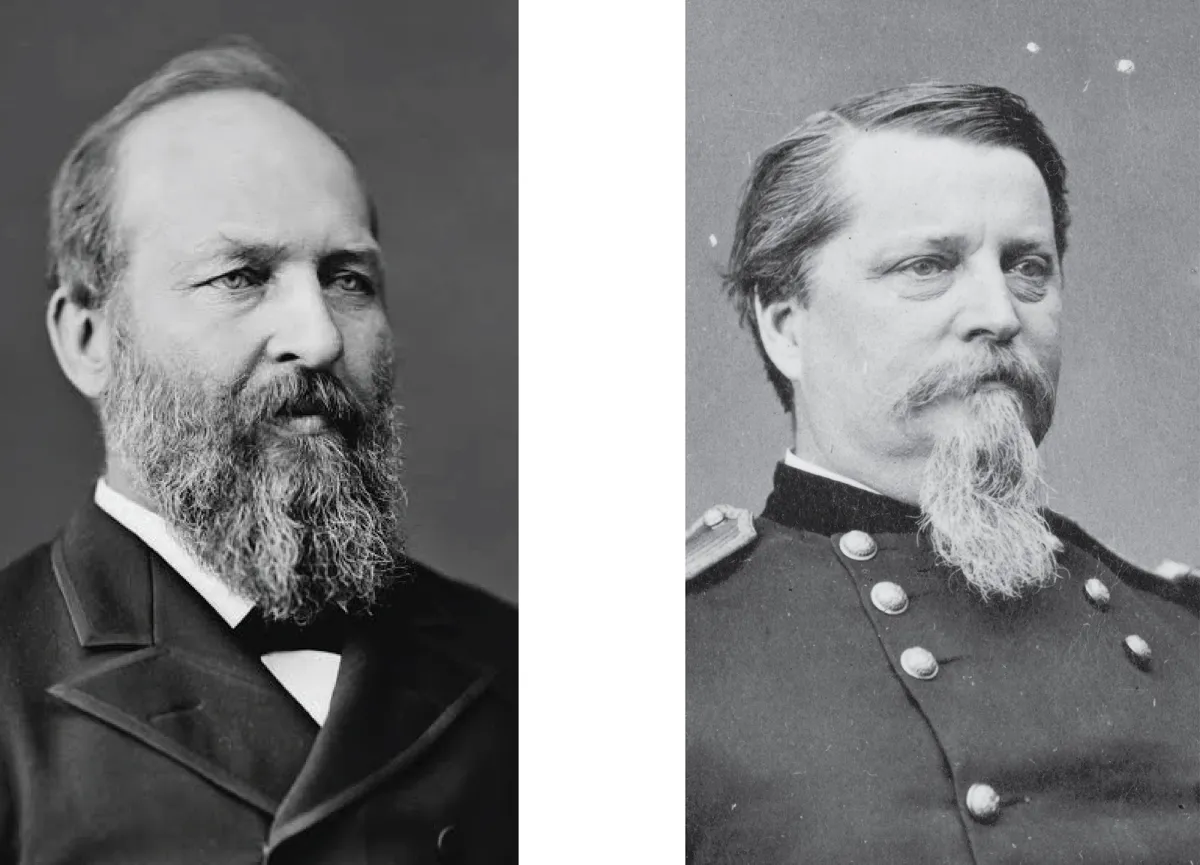

If the Republican Party agreed on anything, it was replacing President Rutherford B. Hayes. Hayes himself, seeing division among his party, promised to serve only one term. At the Republican convention in 1880, the party nominated James Garfield, a longtime congressman from Ohio. Garfield would run against the Democratic nominee, Winfield Scott Hancock, a well-respected former Union general.

After accepting the nomination, both Garfield and Hancock wrote letters to their party’s chairman. That practice was a tradition that let candidates address major election issues. It was also the only form of direct communication between candidates and voters.

In his letter, Garfield called for, among other things, the protection of civil liberties for white and Black Americans; support for schools; the continuation of the gold standard; and negotiations with China to limit the influx of Chinese immigrants, which Garfield compared to the import of foreign goods that needed to be restricted—and to an “invasion.”

Many voters in Western states certainly agreed with that description. The riot in Colorado was just one example of anti-Chinese attitudes, which had grown over the last three decades. Although immigration wouldn’t be the deciding policy issue in the 1880 election, it mattered to many important states.

Despite the Republican party’s rhetoric, its members weren’t anti-immigration. In general, Garfield, Hayes, and other Republicans supported controlled immigration. They wanted to limit Chinese immigration—not crush it completely. The Democratic Party, which had more supporters in the Western states, called for an all-out exclusion.

But a ban at that time was not possible. Chinese immigration laws in 1880 were mostly subject to the Burlingame Treaty, which the United States and China signed in 1868. The treaty opened Asia to more American trade and influence. It also granted open immigration to Chinese citizens and promised them the ability to work, study, and travel freely within the United States. Following the recently adopted Fourteenth Amendment—which guarantees the equal protection of law for anyone under American jurisdiction—states were not supposed to pass any laws that discriminated against Chinese immigrants.

California still tried. By 1880, the California state government had already passed laws attempting to prevent Chinese naturalization. They also targeted Chinese sex workers, leading to deportations. In 1879, Hayes vetoed a California-supported bill in the U.S. Congress to restrict the number of Chinese arrivals.

Voters in Western states were, therefore, critical of Republican immigration policies. Hancock and the Democrats would attempt to leverage that anger in the 1880 election.

The Ballot Issue Then

Americans had many concerns heading into November, including Southern politics following Reconstruction, as well as and tariffs on imported goods. But in October, just a month before the election, one issue rose close to the top: Chinese immigration.

Nowhere was that matter more important to voters than in the Western states, where most Chinese immigrants lived and worked. Hoping to win votes in those states, Hancock and the Democrats appealed to anti-Chinese attitudes.

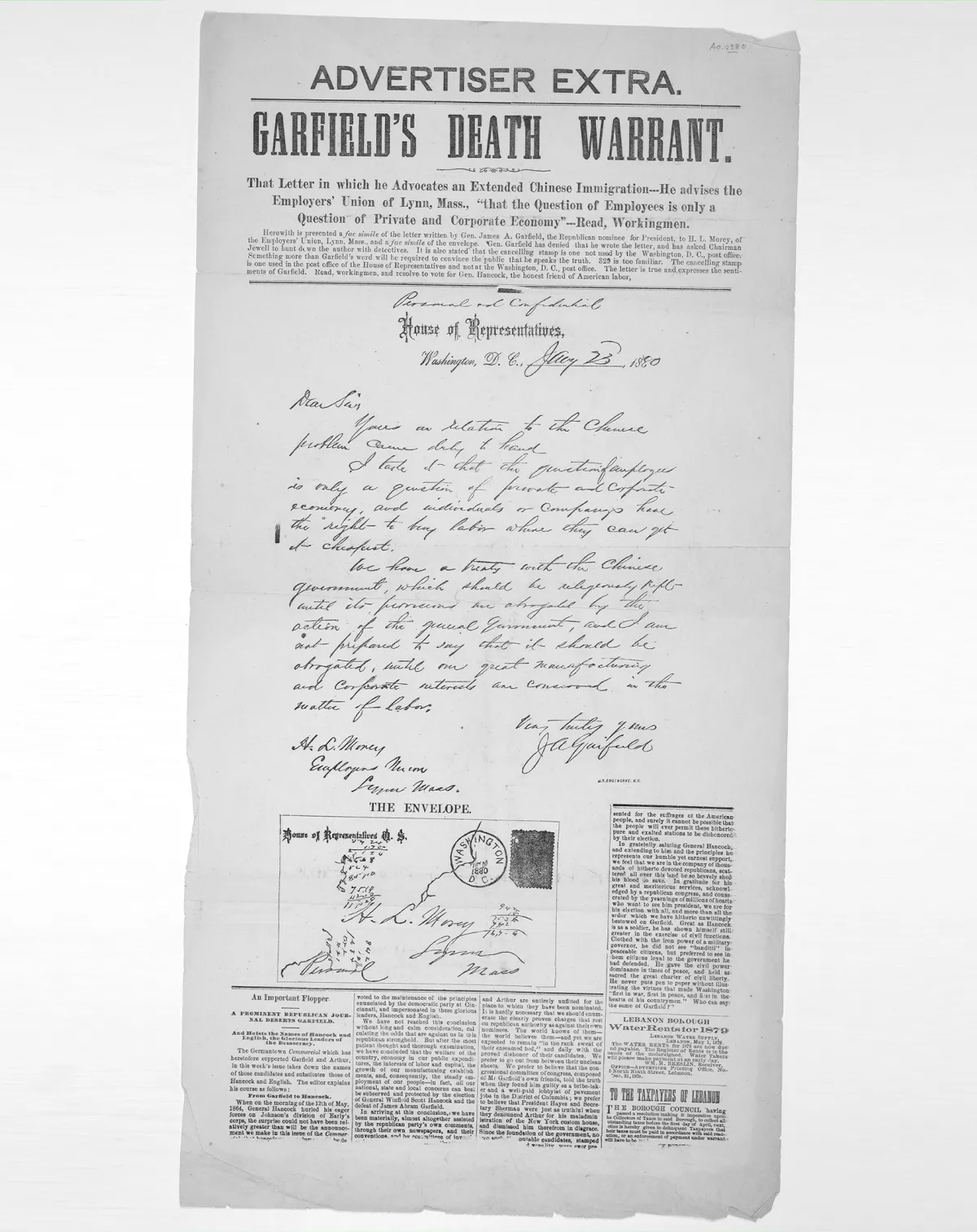

In October, the perfect opportunity fell into their laps. An anonymous person had sent a letter allegedly written by Garfield to Democratic newspapers. The letter said that “individuals and companys [sic] have the right to buy labor where they can get it cheapest.” It was implicit support for unlimited Chinese immigration. On the eve of the election, it made Garfield into the enemy of Western states.

The letter was a forgery. Still, Democratic newspapers ran with it. Half a million copies of the fake letter were sent across the country, weakening Garfield’s support in anti-immigrant Western states. In Colorado, the letter helped spark the Halloween Riot. It seemed Hancock would get a last-minute victory in the West.

But despite winning support in Western states, the Democrats weren’t able to use the forged letter to swing the vote. The popular vote was close. The margin between the candidates was just under two thousand votes, the closest popular vote ever recorded in American history. However, the electoral vote swung more decidedly in favor of the Republican candidate. James Garfield was elected president.

The immigration issue was far from settled. Republicans worried about losing future California voters; they needed to address Chinese immigration. Just before Garfield took office, the United States restricted Chinese immigration—but did not prohibit it. Two years later, in 1882, Congress halted immigration altogether with the Chinese Exclusion Act.

The Ballot Issue Now

Immigration into the United States looks much different now than it did over a century ago. Still, immigration policy could once again decide how some Americans vote in November 2024. More than half of Americans (57 percent, according to a Pew Research Center poll) say immigration should be a top priority for the president and Congress in 2024.

Why are Americans concerned?

Today, most migrants who enter the United States enter through the southern border with Mexico. However, less than half of those migrants are from Mexico. Many are now coming from Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, and Venezuela—nations enduring violent crime and political turmoil. Although in 1880 most Chinese immigrants entered California looking for work, many migrants now seek asylum, or protection for people unable or unwilling to return to their country for fear of persecution.

Immigration across the Mexican border hit record highs in 2023. In December, the U.S. Border Patrol reported nearly 250,000 encounters with migrants, the highest monthly number ever recorded. American cities like New York and Chicago have had trouble housing migrants, leading Democratic leaders to criticize President Joe Biden for not providing enough help once migrants arrive. Republican leaders have also criticized the Biden administration for not doing enough. Some have called for deporting immigrants who have arrived within the last four years. Others have compared southern immigration to an “invasion”—language reminiscent of anti-Chinese rhetoric in 1880.

Outside of Washington, DC, some American voters are opposed to immigration for reasons of identity and safety. In an early 2024 poll, 42 percent of Americans said that “openness to people from around the world” was a “risk to national identity.” In another poll, 32 percent worried that legal immigrants would commit crimes.

Although the right to seek asylum is part of American and international law, leaders in both the Democratic and Republican parties believe in limitations. Former President Donald Trump, whose Republican administration built 450 miles of barriers along the border, has said he will reinstate many of his former immigration policies if reelected—including having asylum seekers wait in Mexico while their cases are processed. While it remains to be seen, Democratic nominee Vice President Kamala Harris may follow Biden’s lead. In June 2024, the Biden administration issued an executive order that restricts asylum applications for migrants who cross Southern border illegally when that border is "overwhelmed" by high numbers of illegal crossings. The ruling introduces restrictions when the number of illegal border entries hits 2,500 people per day.

Even though encounters at the border have dropped off steadily since December 2023, both parties’ leaders support some level of increased border security. As in 1880, how tough those policies appear to voters could determine which presidential candidate they choose.