Regional Politics: Europe and Eurasia

From the war in Ukraine to competition with China, learn about ten key relationships defining the region.

The Europe-Eurasia region is home to some of the largest political alliances in the world.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) is the world’s largest. Out of NATO’s thirty-two members, thirty are European countries. (The other two are the United States and Canada, Europe’s biggest allies.)

And then there’s the European Union (EU), a collection of twenty-seven European countries that form one supranational government—enacting laws that apply across the continent.

In recent history, Europe and Eurasia have often been separated by competing blocks.

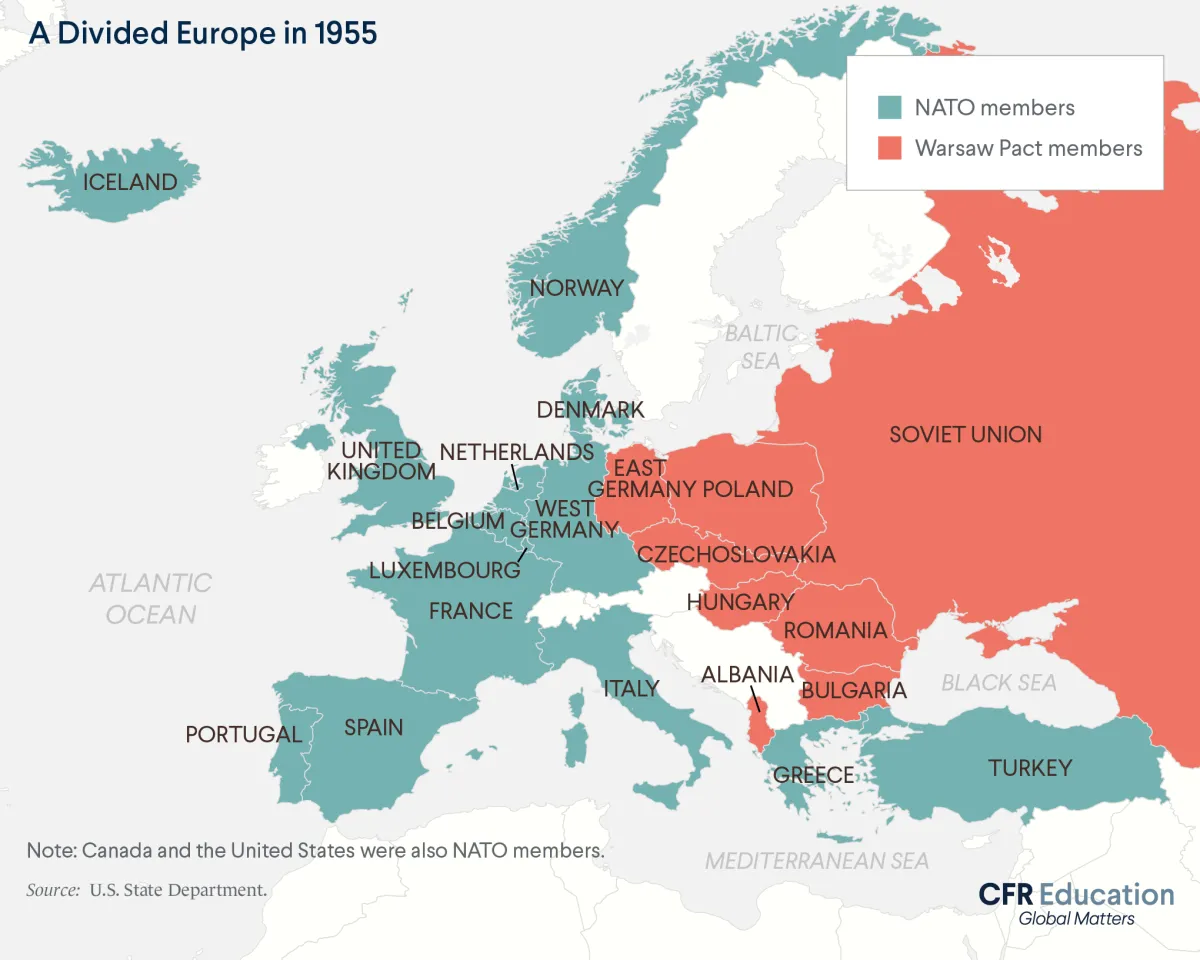

The Cold War saw tensions escalate along East-West lines. Western Europe and their politics were aligned with the United States. Eastern Europe was either formally part of the Soviet Union, or under its influence.

Even after the collapse of the Soviet Union, relations between western Europe and Russia have remained fraught. So have relations between Russia and their former republics. Many former Soviet republics have found themselves caught between their old rulers and the growing alliances of NATO and the EU.

But Russia’s polices represent just one regional issue.

Changing conditions within and outside the EU have also created a new geopolitical reality. Since 2014, a wave of terrorism has swept Western Europe, the United Kingdom, the EU’s second largest military power, voted to leave the bloc, and U.S. President Donald Trump has criticized Europe’s contributions to NATO—threatening the security alliance’s continuation.

What else defines Europe, Eurasia, and its geopolitics?

Here are ten organizations, tensions, and developments that continue to drive events across the region.

The EU: Supranational Politics

Founded in 1993, the European Union (EU) is an economic and political union, created with the goal of promoting peace, security, and prosperity in Europe. From the outside, the EU looks a lot like the United States: it’s made up of departments that are similar to the executive, legislative, and judicial branch of the U.S. government. But the EU is a very different (and unique) political entity. In fact, it’s more like a combination of the United Nations—in which countries are the main decision-makers—and the United States—in which states operate with some autonomy under a federal government. How does the EU work? European citizens are directly represented in the EU parliament (located in Brussels). Individual countries are represented by both their own leaders and officials their governments elect specifically to the EU. With a budget of roughly 190 billion euro, these EU bodies create rules governing everything from farm subsidies, to trade agreements, to data privacy, and more. A range of opinions exists about what direction the EU should take. Enthusiasts seek more integration and push for an even stronger EU. Eurosceptics, meanwhile, are wary of transferring too much power from independent countries to a supranational body.

Brussels and Europe: From EU Law to National Law

Once EU policy is made in Brussels, what happens next? How do these policies actually take effect across EU countries? In most cases, legislation is first approved by the Council of the European Union (which represents governments) and the European Parliament (which represents citizens). A common legislation is a regulation, which functions like a law. Regulations automatically become laws in each member state. One EU regulation, for instance, is Flight Delay Compensation, which guarantees rights for passengers across EU countries. If a member state does not comply with EU laws, they can be sanctioned by the EU’s court. The balance of power between governments and the EU is a major source of debate—from trivial tabloid myths about Brussels’ overreach, to meaningful votes on EU treaties and policies. In 2005, Euroscepticism led to the rejection of a European constitution that would have consolidated EU treaties into a single text (similar to the U.S. Constitution) and given the EU more decision-making control.

NATO: The World’s Largest Alliance

In addition to the EU, many European countries are part of another governing body: the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). NATO is made up of thirty-two countries, thirty of which are in Europe—the United States and Canada are the other two members. The alliance offers member countries a security guarantee—an outside attack on one country will be treated as an attack on every country. NATO formed in 1949 both to promote a democratic Europe and to also defend against Soviet encroachment. Today, it maintains its mission of deterrence and defense. And NATO continues to expand. In 2023, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Finland joined NATO. In 2024, Sweden also became a member. But despite its new additions, NATO’s future has recently been a subject of concern. Over the past decade, NATO members have agreed to defense spending guidelines; each country has committed to spending 2 percent or more of its gross domestic product (GDP) on defense. But countries have been slow to reach that benchmark. In part because of that low spending, U.S. President Donald Trump has long questioned U.S. commitments to NATO—potentially undermining the credibility of NATO’s collective defense mission and calling the future of the alliance itself into question.

Russia and Western Europe: Eurasia’s Cold War

In response to NATO, the Soviet Union formed its own Cold War alliance, the Warsaw Pact. In practice, this divided Europe between an American-backed west and a Soviet-backed east. After the Cold War, East-West relations had a chance at a reset. In a move that remains controversial, NATO offered membership to some former Soviet republics and satellite states. Opponents argued the move alienated Russia, but others countered it accelerated countries’ paths to democracy. Whatever the case, these East-West faultlines continue. Russia maintains that NATO is an aggressive alliance and has violated alleged pledges not to expand into former Soviet countries. Meanwhile, Moscow has also continued to exert influence abroad, most prominently through direct military action, such as its 2022 invasion of Ukraine, but also through more subtle methods such as election interference. Since 2015, Russia has interfered in elections in the United States, France, Germany, and the UK, among other countries—actions that signal a new kind of cold war. This meddling has taken several forms, including promoting disinformation on social media, hacking into campaign email accounts, and channeling funds to select candidates. In so doing, Moscow has sought to promote its preferred candidates and influence national politics.

Russia and Ukraine: Eurasia’s Hot War

Ukraine’s geography has often complicated its politics. Ukraine is sandwiched between Europe's largest powers: NATO and the EU (to the west) and Russia (to the east). Ukraine is not a member of NATO nor the EU. And since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Kyiv is no longer joined with Moscow. That leaves Ukraine caught between two competing spheres of influence—forcing it, for much of its recent history, to perform a balancing act. In 2014, that balancing act became untenable. Many Ukrainians wanted their country to move closer to Europe. Ukraine’s parliament had approved a trade deal that would forge closer economic ties to the EU. However, Ukraine’s president favored closer relations with Russia and rejected the proposal. Protests erupted across the country, forcing the president out of office. Russia responded by annexing Ukrainian lands and arming pro-Russian separatists. Since then, the Russian government has increasingly sought to undermine Ukrainian sovereignty, arguing that Ukraine was historically Russian territory and should not be an independent country. In 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, beginning a full-scale war. The EU and NATO have responded by sanctioning Russia and supporting Ukraine. But many have criticized these organizations for not doing enough to protect the country from years of Russian aggression. Others question whether the billions of dollars spent on the conflict have been worth it.

Serbia and Kosovo: A Diplomatic Stalemate

NATO has had other major tests in recent decades. Since 1999, NATO has maintained peacekeeping operations in Kosovo, a former autonomous province of Serbia. NATO first intervened in Serbia in the 1990s to end the Serbian government’s ethnic cleansing of Kosovar Albanians, a Muslim group making up a majority of Kosovo’s population. Even before the war, Kosovo’s ethnic Albanians believed Kosovo should be its own country. But many Serbians see Kosovo as the home of their Orthodox Christianity—as well as the site of important events in Serbian history. In 2008, Kosovo declared its independence from Serbia. However, Serbia and its powerful allies (including China and Russia) strongly reject Kosovo’s statehood. Serbia has also accused Kosovo of discriminating against its ethnic Serb minority. Despite repeated diplomatic efforts by the United States and the EU, Serbian-Kosovar relations remain tense. Russia is also now complicating things. After Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, its influence over Serbia appears to have grown. Serbian leadership continuously ignores Western sanctions against Russia, and some Western onlookers worry that Russia’s invasion could inspire Serbian nationalists to escalate violence against Kosovo—further destabilizing the Balkans.

Ireland and Northern Ireland: Is Reunification on the Table?

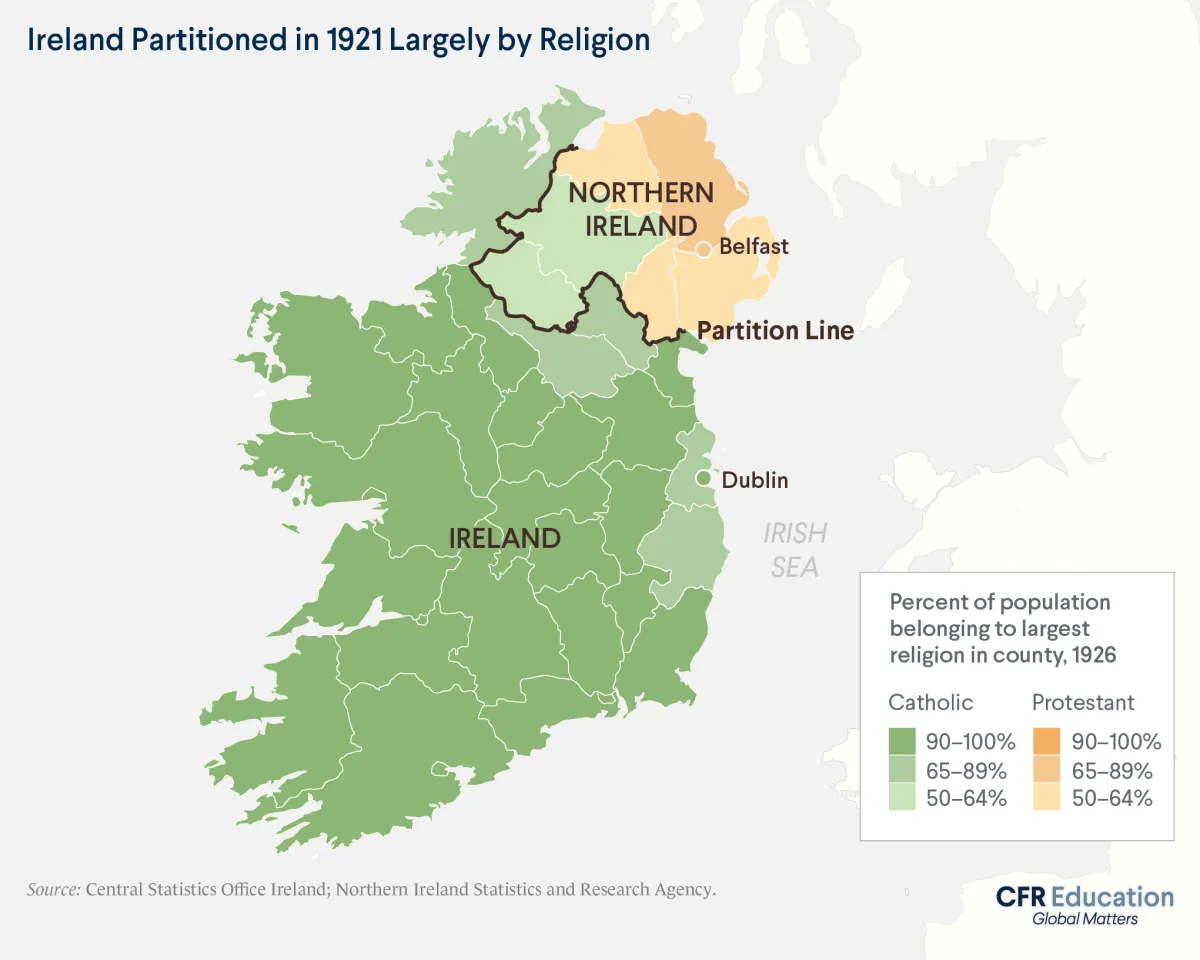

When Ireland gained independence in 1921, several counties in the northern portion of the country remained a part of the United Kingdom. That division laid the groundwork for a decades-long period of violence known as the Troubles. From the 1960s to the 1990s, predominantly Catholic republican nationalists, who wanted Northern Ireland to reunite with Ireland, clashed with both the British military and loyalist Protestant paramilitaries, who wanted Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom. In 1998, the Belfast Agreement—which set up a power-sharing government between the two sides but kept Northern Ireland in the United Kingdom—largely ended the violence. But recent political shifts could signify a growing support for Irish nationalism. After elections in 2024, the republican nationalist Sinn Fein party led Northern Ireland’s government for the first time. Sinn Fein representatives are outspoken critics of the UK government, especially Brexit, and strongly believe in reunification. The party’s leader has advocated for Northern Ireland to hold a referendum within the next ten years that would allow citizens on both sides of the Irish border to vote on reunification.

Turkey: NATO’s Wild Card?

Turkey occupies a unique space in Europe’s regional politics. Its location—bridging Asia, Europe, and the Middle East—puts Turkey at a geopolitical crossroads and, therefore, gives the country significant influence. Turkey has been a member of NATO since 1952 and has maintained close relations with the EU. However, under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Turkey has pursued a more assertive and independent foreign policy, leading to both collaboration and friction with its allies. For example, Turkey has sought to maintain relations both with Russia and China and also with the United States and the EU—countries and organizations that don’t have strong relations with each other. In 2019, Turkey purchased a missile defense system from Russia, angering NATO countries. Meanwhile, Turkey has drawn Western criticism for its human rights practices toward its Kurdish minority. It has also supported neighboring Azerbaijan in recent military operations against Armenia—which human rights advocates characterized as ethnic cleansing. But despite Turkey testing the limits of its relationship with NATO members, both parties have so far been careful to avoid confrontation that could fully rupture their relationship. Still, Turkey’s growing assertiveness on the world stage remains a concern for Western Europe and the United States.

The G7: Is It Still Relevant?

Europe’s partnerships extend both to the east and west under the Group of Seven (G7). The G7 is a block of democratic countries that includes Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. (While it’s not part of the titular seven, the EU also participates in G7 meetings.) Formed in 1975 to address economic concerns, the group has since broadened its focus to coordinate on a variety of transnational issues, including climate change and artificial intelligence. The group is more of an informal bloc than a formal institution such as NATO. That informal structure, as well as the group’s small membership, have proven advantageous, allowing decisions to be made more easily. However, critics argue that the G7 is no longer representative of the world’s economy. In 1980, G7 countries made up just over half of world GDP. By 2023, they made up roughly a quarter. (A similar group, the G20, accounts for more than 85 percent of the world’s GDP and is seen as more inclusive and representative.) Critics also underscore how the G7 has failed to follow through on promises, such as vaccine goals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, although the group may have lost some of its prior influence, recent events like Russia’s war in Ukraine and China’s economic rise have underscored for many analysts that the group still remains useful for generating consensus among a coalition of U.S. allies.

China and the EU: A Growing Rivalry

Looking ahead, Europe’s most consequential relationship may not be with the United States—but with China. China has grown to become one of the EU’s largest trading partners. In recent years, it has also become increasingly tied to European affairs, especially with its support for Russia in the war in Ukraine. That support has led European countries to reconsider their dependence on China. While a longtime economic partner, policymakers in many European capitals increasingly see China as an economic rival—and a threat to European industries. Meanwhile, some Eastern European countries like Hungary and Serbia have gone the other direction, hoping to strengthen ties with China. And then there’s the Arctic, which has become a new geopolitical front. As global temperatures rise, the Arctic remains unfrozen for longer each year, opening previously impassable shipping routes. Countries bordering the Arctic will want to extract the region’s potentially vast natural resources, including gas, oil, and rare earth minerals. China—despite not actually bordering the Arctic—is investing heavily in energy exploration and infrastructure development in the region. European countries worry that China’s Arctic presence could provide Beijing with increased economic and even military leverage.