Laws, Norms, and Democratic Backsliding

Are countries less democratic than they used to be? Learn how democratic principles like checks and balances, free elections, and freedom of the press are under threat around the world.

Since rising to power in 2010, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has systematically chipped away at the foundations of Hungary’s democracy. His government has shut down newspapers, silenced nongovernmental organizations, dismantled the country’s independent courts, and undermined free elections.

In March 2020, the Hungarian parliament delivered stunning new power to Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. It authorized him to rule by decree, meaning he could single-handedly—and without oversight—create laws, much like an emperor or king. While this measure was initially enacted to address the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, it was extended multiple times in 2020 and 2021, during which the government used its authority to restrict civil liberties unrelated to public health concerns. In 2022, as the COVID-19 state of emergency came to an end, a new one was declared due to the war in Ukraine, further prolonging Orbán’s rule by decree.

Today, Hungary is the only country in the European Union that is considered just “partly free.” In April 2022, the European Commission announced its intention to reduce funding to Hungary due to concerns about the country not meeting the European Union’s rule-of-law standards. The announcement was prompted by Orbán's fourth consecutive election victory, which international observers criticized for its lack of fairness.

What’s happening in Hungary is not an isolated incident. Democracies around the world are under siege—not by foreign invaders but by domestic leaders who are weakening their countries’ institutions that protect political freedoms and civil liberties. That trend is known as democratic backsliding.

What is 'democratic backsliding'?

Not long ago, Hungary was a far more democratic country—one with competitive elections and a flourishing independent media landscape. It was one of over a dozen countries to transition from authoritarianism to democracy amid the breakup of the Soviet Union.

The end of the Cold War was a triumphant moment for democracy in Europe. Prominent academic Francis Fukuyama described it as “the end of history” because democracy appeared on track to become the system of government for every country in the world. By the start of the twenty-first century, democracies outnumbered autocracies for the first time.

But soon thereafter, countries began to see many of their hard-fought democratic gains stall and sputter. The world became less free and democratic every year between 2005 and 2023. Only 54 percent of the Asia-Pacific region live under democratic regimes, almost 30 percent of people in Latin American democracies express complete distrust in their political parties, and nearly 70 percent of citizens in Italy, Greece, and Spain say they are not satisfied with the functioning of their democracies.

Several factors have contributed to the trend of democratic backsliding. For one, immense economic challenges—including the fallout from the 2008 global financial crisis, job losses associated with technological innovation and globalization, dramatic inequality, and widespread corruption—have undermined public confidence in democratic leadership and in a system of government that allows for such stark inequalities. Additionally, China has inspired faith in its model, which is premised on the belief that an efficient, nondemocratic government can provide sustained economic growth to its people just as well as—if not better than—a democratic government. China has argued that while Democracies can guarantee certain freedoms, they struggle to pass laws and promote economic growth due to political gridlock. Furthermore, Russia—trying to increase its global influence—has weakened democracies by repeatedly interfering in elections abroad. The United States, France, Ukraine, and the United Kingdom have all accused Russia of election interference.

Democratic backsliding rarely happens overnight. It is often slow, systematic, and difficult to detect—the political equivalent of death by a thousand cuts. First, a president starts questioning the value of a free press. Then, electoral corruption goes unchecked. Eventually, political opponents are barred from running for office or perhaps even imprisoned.

After years of leaders dismantling democratic institutions piece by piece, the result is unmistakable: a society that is less free and fair. Even the world’s most established democracies are not immune from that trend. They too can be eroded, alarmingly quickly.

To recognize where democracy could be in danger, first one has to know how laws and democratic institutions should function. People must be aware of how democratic norms—the unwritten rules about acceptable behavior in democratic societies—protect that form of government from declining.

What is a healthy democracy?

At their core, democracies are systems of government in which people choose who governs them. They do this through regular, free, and fair elections.

The mere presence of elections does not make a country democratic. Plenty of authoritarian countries offer the veneer of democracy by holding elections that are actually orchestrated events.

Cambodia’s National Assembly elections on July 23, 2023 resulted in a sweeping victory for Prime Minister Hun Sen's Cambodian People's Party, which secured 120 out of 125 available seats. The main opposition party was banned from running by the Constitutional Council, a Cambodian judicial body, and its members were threatened and harassed. Hun Sen has held power for 38 years, making him the longest-serving non-royal leader in Asia. The United States and several other democratic nations have denounced these elections, calling them "neither free nor fair" because of the absence of political opposition in the country.

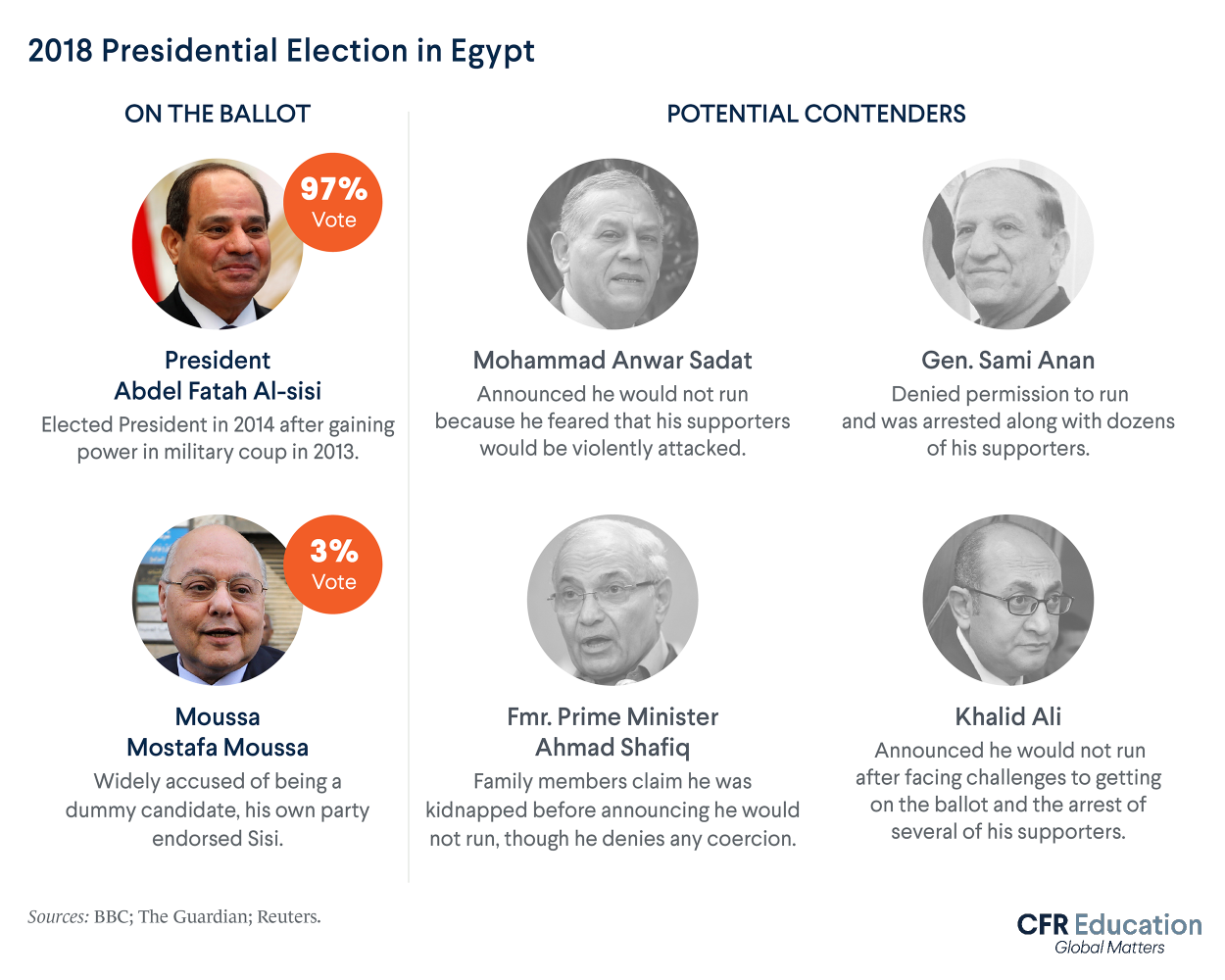

Similarly, in Egypt’s 2018 presidential election, the incumbent leader Abdel Fatah al-Sisi imprisoned, intimidated, or barred every legitimate political opponent from running against him. That left just one handpicked opposition candidate who endorsed Sisi for the presidency. Unsurprisingly, Sisi won reelection with 97 percent of the vote.

In addition to elections, other pillars of democracy include an independent press, a free civil society, and a government that protects individual liberties.

Healthy democracies defend those pillars with both laws and norms. Laws are passed by the government under a constitution and are enforceable by the criminal justice system, the courts, or other government mechanisms. Norms, on the other hand, are rooted in tradition; they are only truly enforceable in the court of public opinion. Both, however, are essential for the health and well-being of a functioning democracy.

The line between what is a law and what is a norm is not always clear-cut, and a law in one country could be a norm in another. For example, freedom of the press is legally protected under the U.S. Constitution but is not a constitutional right in the United Kingdom; there, however, freedom of the press is a powerful norm and expectation.

Strong (or liberal) democracies respect such laws and norms, while weak (or illiberal) democracies can adhere to only a handful. Even so, sometimes the world’s strongest democracies—such as Iceland or Norway—struggle to perfectly embody them. The degree to which countries embrace democratic laws and norms reveals both the strength of a democracy and the extent to which its citizens live in a free and fair society.

Let’s explore those democratic laws and norms—pillars of a healthy democracy—by examining countries where they thrive and where they have broken down in recent years. As we go through each pillar, we'll also look at a map that shows which countries are upholding it and which aren't. Those maps are based on questions from "Freedom in the World" reports by Freedom House, an independent organization that analyzes the status of civil liberties and political rights around the world.

Free, Fair, and Competitive Elections

Elections need to be held without voter intimidation, overly cumbersome registration rules, or disenfranchisement (denying people the right to vote). Many of those requirements are enshrined in a country’s laws. A related norm is that elections should also be competitive. Healthy democratic elections are defined by legitimate and credible opposition candidates able to run against politicians in office.

- Netherlands: Since World War II, the country’s three largest political parties have regularly rotated in and out of power. Sixteen parties have seats in the Dutch parliament, a body of government that encourages collaboration and coalition-building to achieve a majority that can govern the country.

- Philippines: Former President Rodrigo Duterte, who came to power through a free and fair election, regularly jailed prominent opposition figures who criticized his controversial policies. Additionally, vote buying was common around the country; a handful of wealthy families exerting outsize influence on elections.

Checks and Balances

Most democracies have three branches of government in their constitutions or legal codes: the legislative, which creates laws; the executive, which implements laws; and the judicial, which ensures laws adhere to the constitution and enforces those laws. Distributing power across and within multiple branches prevents any one from becoming too powerful. Checks and balances also ensure that laws are in line with the constitution and crafted by an array of elected officials. Additionally, independent agencies and regulators with oversight and autonomy serve as a powerful check on government authority.

- Germany: A controversial 2016 law allowed Germany’s spy agency to monitor the emails and telecommunications of journalists and other foreigners working abroad. But in 2020, the country’s highest court declared the law violated the constitution’s rules on privacy and freedom of speech. The court ordered the law amended in a powerful rebuke of the federal government’s authority. Following the decision, the government accepted the court’s ruling.

- United States: Although the Department of Justice falls under the executive branch, which the president leads, its mission is to defend the U.S. Constitution and enforce the laws of the land. The Department of Justice does not exist to serve as the president’s attorney. However, former President Donald Trump repeatedly questioned that separation of power. He infamously called former Attorney General Jeff Sessions a “traitor” for allowing an investigation into his actions. Trump also demanded “loyalty” from former FBI Director James Comey.

Civil Liberties and Individual Freedoms

Strong democracies defend individual rights—such as freedom of speech, religion, and assembly—under all circumstances. Even demonstrations critical of the government should be permitted. Unhealthy democracies often limit these rights, also known as civil liberties. For example, the prohibition of demonstrations or the classification of dissidents as criminals or terrorists undermines freedom and healthy democratic governance.

- Guatemala: In Guatemala, mass protests began on October 2, 2023, demanding that the country's Attorney General Consuelo Porras’ resign for attempting to eliminate President-elect Bernardo Arévalo’s Seed Movement Party. Initiated by the 48 Cantones of Totonicapan, a prominent Indigenous organization, these protests united Guatemalans from diverse backgrounds with a clear political objective. Unlike the 2015 “Guatemala Spring” protests, which mostly involved the urban middle class and only led to the resignation of then-President Otto Pérez Molina, the 2023 movement has reflected louder more widespread calls for democratic change.

- Hong Kong: Residents of Hong Kong have seen their right to free speech and assembly rapidly deteriorate in recent years. The government—heavily influenced by China—has violently broken up protests. Law enforcement have even arrested those who have demonstrated against policies that bring the autonomous territory closer to China. A 2020 law effectively eliminated free speech, including criminalizing calls for the territory’s independence. In that instance, the government used the law to directly undermine a pillar of democracy.

Equality Before the Law

All citizens should be treated equally, regardless of gender, race, sexuality, ethnicity, religion, wealth, or other metrics. Such equality cannot be undermined through legislation, and special laws can even explicitly safeguard the rights of vulnerable groups so that all citizens—including minority populations—feel safe and secure. Though not necessarily illegal, publicly vilifying certain groups is a violation of the democratic principle that all citizens be treated equally.

- Brazil: The country has one of the highest murder rates of LGBTQ+ people in the world. In 2018, two former police officers assassinated a Black lesbian politician—one of the country’s most outspoken pro-minority voices. The following year, Brazil’s first openly gay member of the National Congress resigned for fear of his life. Brazil’s government has failed to pass meaningful legislation to curb that violence. Moreover, the country’s former-president, Jair Bolsonaro, openly promoted homophobia.

- India: As a religious minority group comprising 14 percent of the nation’s population, Muslims in India have historically endured multiple forms of discrimination. In 2022, this discrimination persisted as certain local governments carried out “punitive” property demolitions, specifically targeting low-income Muslim communities, without the requisite legal authorization or due process.

- Czech Republic: A quarter of a million Roma people live in the Czech Republic, and 66 percent of the Czech population has unfavorable views toward them. Widespread discrimination against Roma people has led them to live in segregated settlements where they face housing deprivation and the threat of forced evictions. Many Roma children attend underfunded schools and leave the educational system early.

No One is Above the Law

The same rules apply to private citizens as well as elected officials in strong democracies. Just as equality before the law protects the rights of minority groups, no one being above the law ensures elected officials cannot abuse their power.

- Argentina: On December 6, 2023, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, Argentina's Vice President, was sentenced to six years in prison and a lifetime ban from holding public office. Kirchner was convicted of a $1 billion embezzlement scheme which diverted funds to a business associate of the Kirchner family through 51 public roadwork contracts. Cristina’s late husband, Néstor Kirchner, served as president from 2003 to 2007, and she herself held the office from 2007 to 2015; the embezzlement occurred over their combined twelve years in power. The sentence remains provisional until all appeals are considered and Kirchner enjoys immunity from arrest due to her role as the Vice President.

- Lebanon: Corruption dominates Lebanese politics, with power concentrated in the hands of certain families and former warlords. Although the government has enriched individuals with close connections, it has also struggled to provide basic services, contributed to a failing economy, and created the conditions that led to a dramatic explosion in the Beirut port, which killed more than 190 people in August 2020.

Civilian-Controlled Military

In strong democracies, militaries are accountable to the people and act on the orders of elected officials. Indeed, in many cases, the commander in chief (the head of the military) is the president—an elected civilian leader. In this way, militaries do not have the authority to unilaterally carry out actions domestically or abroad. That’s why coups—military takeovers of civilian governments—are strictly seen as undemocratic.

- Taiwan: Military generals partly composed an authoritarian government that ruled Taiwan for nearly forty years until 1987. That changed with Taiwan’s democratization. A 2000 law banned military officers from serving in government. The legislation also gave the civilian president control over the military.

- Niger: On July 26, 2023, a faction of the Niger military staged a coup, overthrowing President Mohammed Bazoum. They cited the “deteriorating security situation” caused by the ongoing conflict with extremist groups. Rates of extreme poverty, along with climate change-driven droughts imperiling agriculture, further compound the crisis. This coup marks the seventh military takeover in the West and Central Africa region since 2020.

Independent Media

A free, diverse, and independent media plays a vital role in healthy democracies by shining a light on abuses of power. Although government-funded outlets can and do exist (the British government, for example, funds the British Broadcasting Corporation, or BBC), strong democratic governments do not limit the creation of other media organizations, inhibit their ability to operate, or vilify journalists and the press. Though not inherently illegal, vilifying the press is a violation of a democratic norm.

- Norway: The country is home to a wide range of independent media outlets. Norway’s constitution even says the government has a responsibility to “facilitate an open and enlightened debate,” and in 2016 the Norwegian government established a Commission on Media Diversity that has expanded the media landscape through measures like subsidizing ethnic and minority-language media.

- India: Though India is the world’s largest democracy, its government has increasingly targeted the country’s free press. In 2019, the government cut off internet access and blocked social media sites for seven months in Kashmir to limit protests following the passing of a controversial law. Police intimidated journalists who reported on the region’s unrest.

Vibrant Civil Society

Strong democracies embrace political participation. These countries are home to organizations such as nonprofits and unions, which allow citizens to organize to achieve their political and social goals. Those organizations are collectively known as civil society. Like the media, civil society can expose abuses of power and violations of democratic norms. Rarely do laws say countries need to have civil society organizations, but such institutions serve as vital pillars of healthy democracies.

- Ghana: Independent policy think tanks have encouraged political participation by training thousands of citizens to educate voters and monitor elections. That effort has contributed to Ghana having among the most peaceful and transparent elections in Africa.

- Turkey: Under the presidency of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey has rapidly descended into authoritarianism. One of the biggest victims is civil society. Erdogan has shut down over 1,500 nonprofits and nongovernmental organizations that deal with refugees and domestic violence. Moreover, Turkish law enforcement has arrested union organizers, teachers, and activists on charges of disloyalty to the government. Turkey has also imprisoned more journalists than any other country in the world over the past decade.