Economics: East Asia & The Pacific

You’d never guess from the modern skylines of Shanghai, Seoul, and Singapore, but in 1950, these cities were in some of the world’s least developed countries.

You’d never guess from the modern skylines of Shanghai, Seoul, and Singapore, but in 1950, these cities were in some of the world’s least developed countries. Nothing short of an economic miracle took place in the region after World War II, as Japan rebuilt and grew rich, and Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan—known collectively as the Four Asian Tigers—followed closely behind. But the most impressive story is of China. In just thirty years, economic reforms helped lift over 800 million Chinese people out of poverty. China is now the world’s second largest economy and the largest trading partner of over seventy countries—and it has set even loftier ambitions with its multi-trillion-dollar global infrastructure project called the Belt and Road Initiative. As the region’s economies boom, many experts project, not surprisingly, that this is beginning of the “Asian century.”

Japan and Four Tigers Drive Asia’s Economic Miracle

In the twentieth century, several East Asian countries pulled off an economic transformation so dramatic that many economists called it a miracle. Looking to rebuild after World War II, Japan developed its manufacturing sector, emphasized exports, and invested in education and infrastructure. These reforms, along with the introduction of strong labor laws and the overhaul of its old feudal system, set Japan on a trajectory of spectacular growth and took it from the ninth largest world economy in 1950 to the second largest by 1968. Japan set the standard, and Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan—dubbed the Four Asian Tigers—followed suit, drawing inspiration from the Japanese policies that sparked unprecedented growth. Today, these Asian countries enjoy high standards of living and are home to some of the world’s largest companies, like Toyota and Honda in Japan and Samsung in South Korea.

Reforms Launch China’s Rise to Global Economic Superpower

Observing the country’s large population and yet unfulfilled economic and geopolitical potential, Napoleon allegedly once called China a sleeping giant that would one day wake up to shake the world. The last thirty years have shown that the giant is now awake. China more than quintupled its GDP between 1977 and 1997, and since 1977, 850 million Chinese people have risen out of poverty. Largely responsible for these developments were market-oriented economic reforms that took off in the late 1970s. Within a few years, farmers could sell crops in local markets, and China opened the country to foreign investment and loosened control of prices and wages. The Shanghai stock exchange reopened in 1990, and China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. These reforms, plus China’s large supply of cheap labor, helped to establish China as the world’s largest manufacturer and second largest economy.

Long-Term Challenges Temper China’s Rise

China’s economic rise has been one of the most stunning stories of the last few decades, but it might not be an unstoppable force. While China is poised to overtake the United States in a few years to become the world’s largest economy, it still faces major challenges to growth. The country is aging quickly (in large part due to the one-child policy active from 1979 to 2015), creating demographic imbalances. Between 2012 and 2017, the working-age population declined by twenty-five million people; continued low birth rates will prolong this trend, while the number of aging people who need to be supported by their families or the state keeps climbing. At the same time, China faces competition from other developing countries where manufacturing costs are cheaper, as well as high debt, which threatens long-term economic health. As a result, growth has slowed over time: according to China’s government, the economy has grown at a rate of 6 percent in 2019, which is still quite high but considerably down from 12 percent a decade earlier.

Up-and-Coming Economies in Southeast Asia Fuel Region’s Growth

As China’s economic growth slows, Southeast Asian countries are stepping in to fill its shoes—literally. The footwear and textile industries in Southeast Asia are in the midst of a production boom, just as China’s market share begins to slip due to rising labor costs and trade disputes with the United States. These are just two industries that are driving growth in the region’s developing economies, where the workforce is young and growing. Indonesia’s economy is set to grow larger than the United Kingdom’s by 2020 in terms of GDP based on purchasing power parity (which accounts for the cost of goods and services across countries). And other Southeast Asian countries like the Philippines, Vietnam, and Myanmar have grown at a rate double the world average. With their business-friendly environments and favorable demographics, economists believe these Southeast Asian countries will join China in powering Asia’s growth for the coming decades.

Friends Close, Enemies Closer: A Highly Integrated Region

East Asia is one of the most economically interconnected areas in the world: 50 percent of the region’s total trade is conducted within the region itself. This integration has been crucial to the region’s economic success. In Southeast Asia, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) members recently established the ASEAN Free Trade Area, allowing member countries to import and export 90 percent of goods from their neighbors without paying extra tax. In Northeast Asia, no political organization like ASEAN exists because of the geopolitical and historical tensions between neighbors, but that hasn’t stopped Japan, China, South Korea, and Taiwan from prioritizing their economic interests to become each other’s largest trading partners. Across the region, several countries—including Australia, Brunei, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Vietnam have created the world’s third largest free trade area, coming into effect in December 2018.

“Factory Asia” Produces World’s Goods

The region’s economic integration doesn’t just benefit Asian countries—it helps the whole world. Together, Asia’s manufacturing sectors create a network of cross-border supply chains that create goods for export, giving the region the nickname “Factory Asia.” The typical production process of an iPhone is an example of Factory Asia at work: many iPhone displays and cameras are made in Japan, many of their touch-ID sensors are from Taiwan; their batteries are often made in South Korea; their audio chips come from countries such as Singapore; and in most cases, all the pieces are finally assembled in a Chinese factory before being shipped around the world. So even though your phone or laptop might be “made in China,” chances are that it’s actually the product of many Asian countries.

China Overtakes United States to Become World’s Largest Trading Partner

China is the largest trading partner of about seventy countries around the world, almost double that of the United States. With the help of Factory Asia, China exports goods as diverse as computers, phones, and stuffed animals, and imports goods from around the world to meet the demands of its population. China insists that it only seeks to promote cooperation with its trade partners, but some countries are wary that their reliance on China for trade might give China the upper hand in economic and political negotiations. For example, when South Korea agreed in 2016 to allow the United States to set up a missile defense system in South Korean territory, China disapproved and slapped South Korea with sanctions. After one year and tens of billions of dollars in losses owing to hampered trade with its largest trading partner, South Korea relented and promised China it would not expand the missile defense system, in exchange for a resumption of normal trade relations. In another episode, China blocked exports to Japan of rare earth minerals, which Japan needs to manufacture cars and missiles, after an incident involving disputed islands in the East China Sea. China even halted imports of Norwegian salmon for years after Norway angered China by awarding a Chinese pro-democracy activist the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010.

High-Speed Rail Drives Growth in Asia

In 1964, Japan inaugurated the iconic, 200-mile-per-hour Shinkansen, known as the bullet train—the world’s first high-speed rail. In the following decades, South Korea and Taiwan replicated Japan’s success. But no story is more impressive than China’s. In just the last ten years, China has gone from having zero miles of high-speed rail to building the world’s largest network—an astounding 17,000 miles, longer than all the high-speed rail in the rest of the world combined. The high-speed train from Beijing to Shanghai takes just over four hours and goes twenty-one times a day—each trip covers the same distance the three-times-a-week New York–Chicago Amtrak train takes nineteen hours to cover. In many cases, high-speed rail has improved integration by connecting small cities to bigger ones and making business between economic centers more efficient. Asian countries are even planning to build a high-speed rail from China through Southeast Asia to Singapore, further integrating the region’s economies.

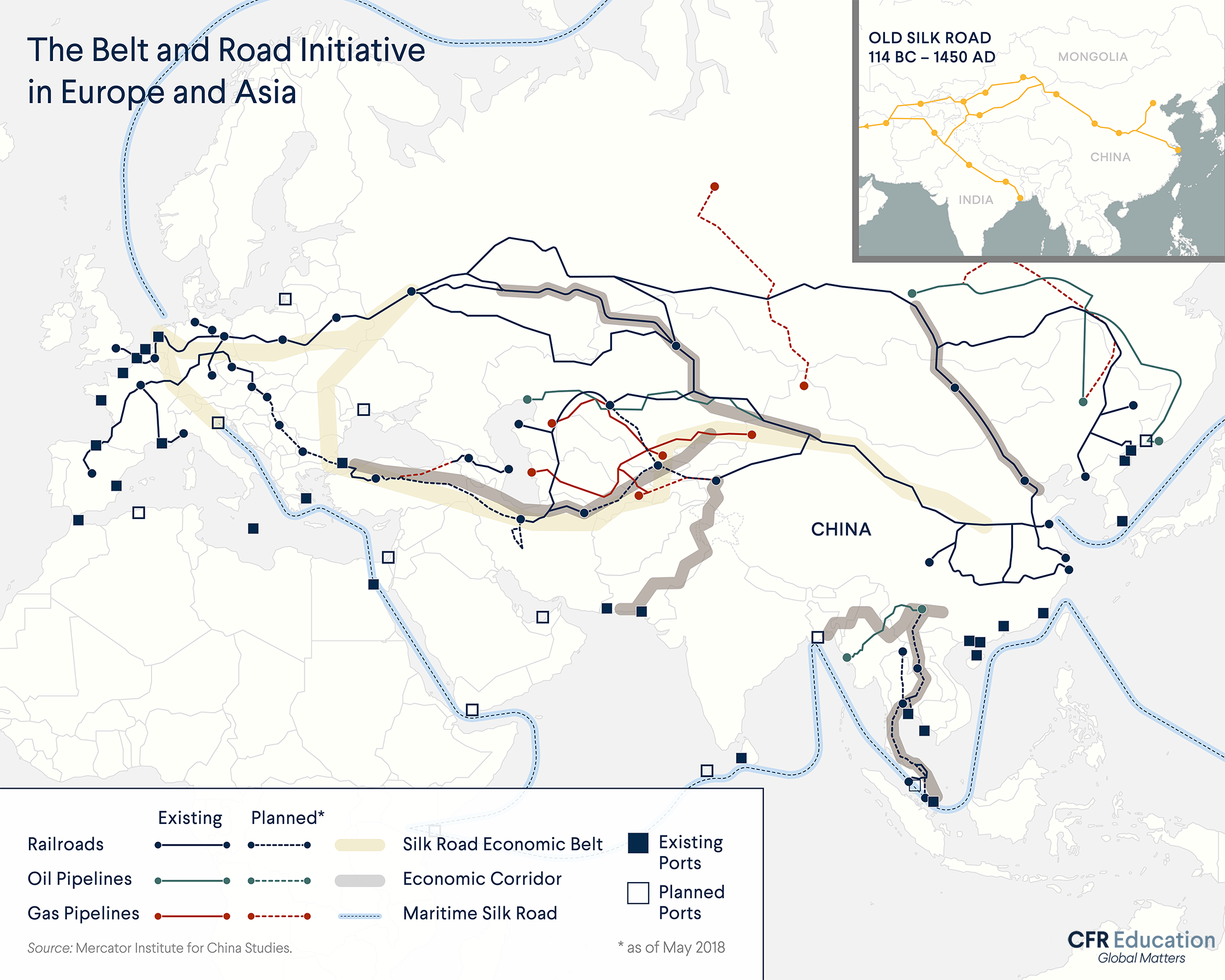

China Promises BRI Will Close Region’s Infrastructure Gaps

Japan’s bullet trains stand in stark contrast to the region’s least-developed countries, where infrastructure is lacking. According to the Asian Development Bank, Asia needs at least $1.5 trillion in infrastructure investments to keep up with its growing population and economies. China has been all too happy to address these shortcomings through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), an ambitious trillion-dollar global infrastructure development and investment plan. Southeast Asia in particular features prominently in China’s plans, with projects like high-speed rail in Laos, port construction in Myanmar, and canal development in Thailand. With projects planned in more than 125 countries, $90 billion already invested, and several hundred billion dollars committed, BRI promises to address many countries’ need for infrastructure funding. By connecting developing economies, BRI could lift thirty-two million people out of poverty, according to World Bank predictions, as long as China adheres to high transparency, environmental, and social standards. At the same time, critics are concerned that these infrastructure projects drown developing countries in debt that they are unable to repay, as has already happened in Sri Lanka.

Asia as New Center of Global Economy

Europe dominated the world economy in the nineteenth century and the United States in the twentieth century; but now many experts believe that the world is entering the Asian century. By 2050, Asia is expected to comprise over half the world’s economy, compared to just over 30 percent today. The boom has already begun, as East Asia’s economy grew at over 5 percent in 2018, compared to a world average of 3.6 percent. It’s now the biggest market for foreign goods, and consumers there buy more cars and phones than those in any other region. International companies will continue to take advantage of this trend, opening more branches and focusing more on Asia to stay close to the new center of the global economy.