People and Society: Asia

East Asia and the Pacific is the world’s largest region, accounting for nearly one-third of the global population.

Asia is a densely populated and immensely diverse region.

India, for example, is more populous than all of North America and Europe combined. It’s home to 1.4 billion people and has twenty-two official regional languages. Meanwhile, Bangladesh accommodates a population roughly half the size of the United States—in an area the size of Iowa.

And then there’s China. Just like India, China has roughly 1.4 billion people, making it one of the world’s most populous countries. In fact, China has more people than all of its neighboring countries (excluding India) combined. Like South and Central Asia, East Asia is also religiously diverse, with large numbers of Buddhists in Japan and the world’s largest Muslim population in Indonesia.

Asia’s massive populations have contributed to massive economic growth in recent decades. This has dramatically improved living standards for millions: over the past half-century, average life expectancy in East Asia has risen by an astounding thirty years and is now seven years higher than the global average. From top-performing schools to well-equipped health-care systems, people in many Asian countries are leading healthier and more productive lives.

But economic and population growth hasn’t been without its downsides. Factors like pollution, overcrowding, and an aging population across Asia threaten quality of life. High populations also leave the region—particularly South Asia, already prone to floods and heat waves—more vulnerable to climate change and the spread of disease.

Of course, population and demographics are just a couple ways of understanding Asia’s culture and people.

What else shapes everyday life in the region?

Here are ten features and trends that define the experiences of many across Asia—in both positive and negative ways.

For Many, Daily Life Is City Life

Roughly six out of ten people in the world live in Asia. And about half of all people in Asia experience daily life in cities. Megacities—cities with more than ten million people—dot the landscape. Asia has over twenty megacities, many in India and China. Such large populations, especially when concentrated in small areas, face pressing challenges: natural disasters have a potentially more devastating effect, and disease can spread quicker. But urban spaces also have many benefits. In China, cities have played a large part in the country’s economic gains, helping lift millions out of poverty. Cities like Beijing and Shanghai are also working to make daily life easier by adopting urban planning strategies to create so-called fifteen-minute communities—neighborhoods with quick access to things like health services and schools. As the world continues to urbanize, Asia’s megacities offer insight into what the future might look like for many across the globe.

Religion Unites Millions, But Also Divides

The largest Hindu, Buddhist, and Muslim populations in the world are in Asia. India is home to nearly one billion Hindus, as well as most of the world’s Sikhs, Jains, Zoroastrians, and Baha’is. Buddhism is the main religion in most Southeast Asian countries, with Cambodia and Thailand representing the largest majority Buddhist countries in the world. And Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, and Pakistan have the world’s four largest Muslim populations. Asia’s vast and diverse religions unite millions across the continent around shared identities. Religious discrimination, however, has often been a divisive—even violent—force in the region. Tensions between Hindus and Muslims go back to before 1947, and religious violence has erupted occasionally since. In China, religious groups face persecution under the officially atheist Communist Party. In the Chinese region of Tibet, for instance, it’s illegal for Tibetan Buddhists to publicly praise or own a portrait of the Dalai Lama, their spiritual leader. The Chinese government has also committed human rights abuses in the Muslim-majority Xinjiang Province. In Buddhist-majority Myanmar, the country’s Rohingya Muslims and other ethnic minorities have been subjected to persecution and violence. Faith, identity, and politics continue to shape the region, influencing both social cohesion and fueling ongoing conflicts.

Language Reveals Population—and Power

Asia’s vast diversity is reflected in its languages. India has twenty-two official regional languages. And Indonesia, a country of six thousand inhabited islands, has hundreds of languages, six recognized religions, and hundreds of ethnicities. By comparison, East Asian languages are much more homogeneous. For instance, despite having many regional dialects, China has only one official language—Mandarin. More than 80 percent of people in China speak Mandarin. The same is true for South Korea and Japan: each country has one official language spoken by over 90 percent of the population. In these cases, language reflects ethnic demographics. Japan is 98 percent ethnically Japanese, and both North and South Korea are 99 percent ethnically Korean. Even China, a country of more than one billion people, is over 91 percent Han Chinese. Language also reflects political trends. For instance, since the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, Russian language instruction has substantially decreased in the former Soviet republics of Central Asia, with some countries even passing laws to restrict its usage in certain settings. Instead, these countries are articulating distinct national identities by promoting their native languages. Younger generations are also increasingly opting to study the languages of rising powers like China.

New Female Leadership Faces Old Prejudices

Unlike other regions of the world, many of modern Asia’s most powerful leaders have been women: Sri Lanka’s Sirimavo Bandaranaike became the world’s first female prime minister in 1960; Indira Gandhi, the daughter of India’s first prime minister, served as prime minister for almost sixteen nonconsecutive years; Pakistan’s Benazir Bhutto became the first woman to lead a Muslim-majority democratic country, followed by two female leaders in Bangladesh. More recently in the 2010s, Nepal, South Korea, and Taiwan all elected their first female heads of state. But female leadership hasn’t always meant strides in gender equality. As in other parts of the world, many women in Asia face a gender wage gap, sexual harassment, and social discrimination. Even in countries with a history of female leadership, progress toward changed gender norms has moved slowly. This is partly because once in power, many of Asia’s female leaders have faced significant opposition—protests, coups, and even an assassination. Still, public opinion is changing. Many across East Asia believe women and men make equally good leaders. In a 2023 poll, nearly 80 percent of male respondents agreed that both sexes made for strong political leaders. Despite this, women remain underrepresented in top political positions in many countries across the continent; in Central and South Asia, for example, only 9.5 percent of 2024 Cabinet ministers were female.

The Average Person Is Getting Older

How many people are sixty-five years old or older? Globally, the answer is one out of every ten people. But in Japan, it’s nearly three out of ten. Across East Asia, populations are rapidly aging. This poses major consequences for the region’s future economy. An aging population usually means a loss of workers and an increase in public spending to care for the elderly. Many observers warn that China—where one-third of the population will be over sixty by 2050—will struggle to care for hundreds of millions of its elderly citizens. Experts attribute this demographic trend to low fertility rates—the average number of babies that one woman has over her lifetime. To maintain its current population (assuming there is no immigration), a country needs a fertility rate of 2.1. In 2023, South Korea’s rate was 0.72. Aging populations and falling birthrates also correspond to new attitudes. When asked if women have an obligation to bear children, or if they should decide for themselves, nearly 80 percent of people in Japan said women should decide. The view is also generational; in South Korea, far more younger people (92 percent) than older people (47 percent) believe women should decide.

For Some Students, Test Scores Determine the Future

Many experts credit education as one factor in East Asia’s immense economic growth. Even with a rising population, East Asia has maintained high enrollment and education quality. In fact, the subregion boasts some of the highest education scores in the world. The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) is one global test often used to compare educational levels across countries. Although experts debate the test’s effectiveness, it provides revealing data about students’ aptitude in subjects like science, reading, and math around the world. According to the 2022 PISA, the top five countries were Singapore, China, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea. While there are many explanations for East Asia’s dominance, one has to do with an educational system that emphasizes preparing students for notoriously difficult college entrance exams. For many students across East Asia and the Pacific, future success depends on their scores. In China, students take the “gaokao,” the world’s largest academic test: in 2024, more than thirteen million Chinese students took the test. Over the two days of the exam, some parents wear red—an auspicious color in Chinese culture. In some regions, less than four out of ten students who take the exam get into college. Test culture puts extraordinary stress on young people. Studies have linked the pressure to perform with teen suicide and increased levels of depressive symptoms.

Business and Vacation Destination

In 2023, the most visited country in Asia wasn’t its largest, China. It was Thailand. Over 28 million people visited the Southeast Asian country—enjoying over 1,500 miles of beaches, 133 national parks, ancient temples, and cheap and delicious food. (Japan was a close second when it came to yearly tourists—many of whom visit during the country’s cherry blossom season in the spring.) Asia’s tourism is only growing. Airlines are increasing the number of flights to the region. As of June 2024, over five hundred thousand hotel rooms were under construction across Asia. Tourism isn’t just a boost to economies. Some countries are also using tourist events and attractions to build their global influence. Singapore, for instance, has seen a steady rise in tourism over the past decade. The small island country hosts international sporting events, concerts, and business meetings—helping elevate the country’s status. Its partnership with Hollywood hasn’t hurt either; as the luxurious setting for the rom-com Crazy Rich Asians, Singapore saw a tourist spike after the film’s release.

The World Nomad Games: Diplomacy Through Goat Wrestling

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Central Asian countries have taken steps to reassert their own national identity. One method has been sports. Drawing on its nomadic culture, Kyrgyzstan launched the World Nomad Games in 2014. Held every two years with more than eighty participating countries, the Olympics-style gathering boasts over twenty sports. Thousands of athletes compete in events like horseback archery, hunting with eagles, bone tossing, and various types of wrestling. Like most international sporting events, the World Nomad Games also serve as a channel for diplomacy. At the 2024 Games, Kazakhstan brought together athletes from around the world, including the United States, China, and Russia (which had been barred from several other events, including the 2024 Olympics). Kazakhstan stated that it wanted the games to be an apolitical celebration of cultures, but hosting the games also supports the country’s broader attempts both to assert itself as a growing figure on the world stage, and to maintain what it refers to as a “multivector” approach to foreign policy, which seeks to balance relations with Russia, China, and the West alike.

From Bollywood to Tollywood, Indian Blockbusters Attract a Worldwide Audience

India makes more than 1,500 movies a year—almost triple the number that Hollywood produces. The cultural significance of these films cannot be understated. Across India, fans have built temples in honor of their most beloved stars. Bollywood—a spin on Hollywood and what many people think of as synonymous with Indian filmmaking—is just the Hindi cinema industry based in Mumbai (formerly Bombay). Other hubs include Tollywood for Telugu-language films and Sandalwood for Kannada-language films. Indian films might be famous for catchy, colorful musical numbers, but they also reflect India’s diversity. In one Bollywood blockbuster, Two States, star-crossed lovers navigate their different backgrounds from Punjab and Tamil Nadu—two states from the north and south of the country. The film industry is also one of India’s most prominent cultural exports. One Tollywood movie, RRR, received international acclaim and won an Oscar for Best Original Song, the first Indian song to do so. Beyond American audiences, Indian cinema’s fan base spans Africa, Central Asia, the Middle East, and even across the border in Pakistan.

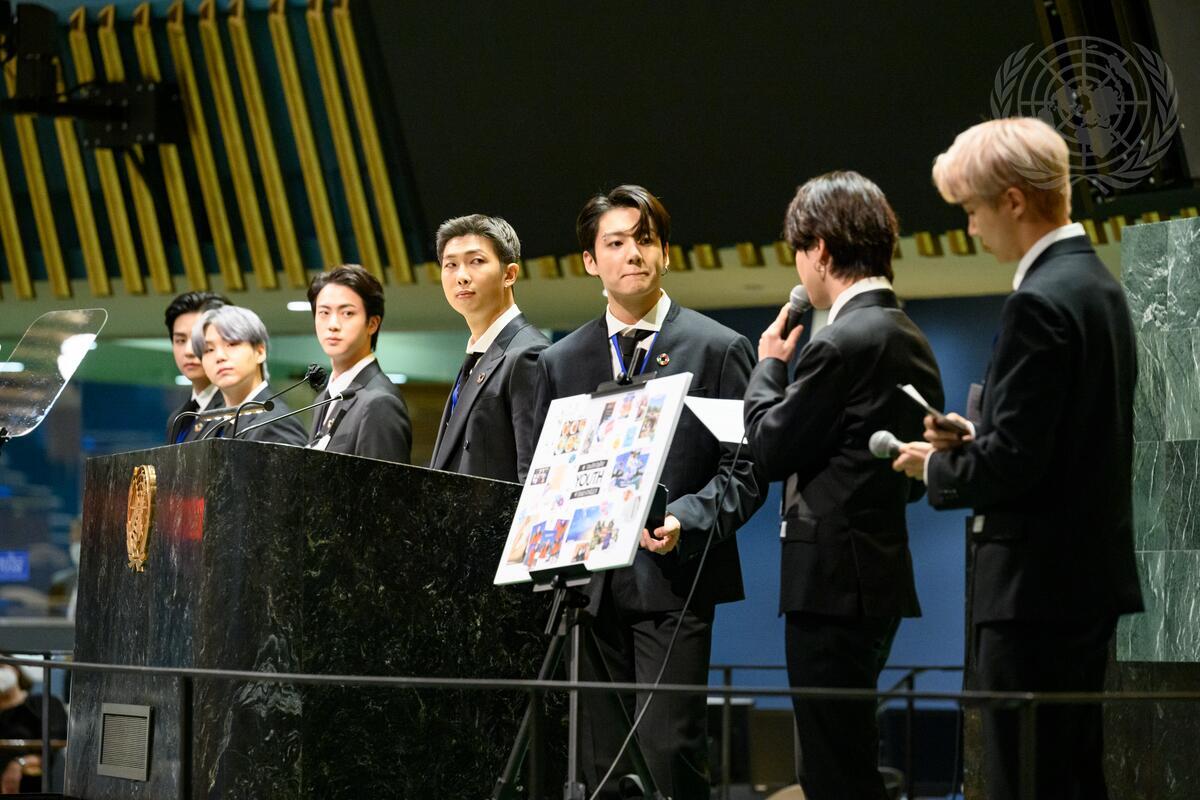

K-Pop – South Korea’s Cultural Export

People around the world are falling in love with Korean culture. Korean restaurants have exploded in popularity. So has Korean cinema, through productions like Parasite (the first foreign film to win Best Picture at the Oscars) and Squid Game (one of Netflix’s most-watched programs of all time). But nothing has taken off quite like Korean music. After the song “Gangnam Style” went viral in 2012, Korean pop music—known as K-pop—exploded worldwide. More than a decade later, groups like BTS and Blackpink have garnered millions of fans, selling out tours in minutes. BTS was the world’s top-selling music act in 2021. However, the group’s influence reaches far beyond the stage. BTS has raised more than $6 million with their UNICEF youth mental health initiative. The seven-member group also visited the White House in 2022 to address anti-Asian crimes and has spoken at the United Nations General Assembly three times. The popularity of Korean music not only helps boost the country’s economy—cultural exports account for more than $12 billion a year—but also helps grow Korea’s global influence.