People and Society: Middle East and North Africa

Learn how culture, demographics, and social trends shape everyday life in the region.

The Middle East is the birthplace of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. It is, therefore, a region of great diversity. While Arabs compose the majority of the Middle East’s population, the region is also home to Berbers, Kurds, Jews, Persians, Turks, and a vast array of other ethnic and religious minorities.

Such diversity does not necessarily translate into equality. Religious and ethnic minorities often face legal discrimination within their own countries. Women, too, fight for equal rights in a region with some of the lowest rates of female political participation in the world.

However, cultures are not exclusively defined by their political leaders, nor are regions reducible to their hardships. In everyday life the Middle East and North Africa must certainly contend with authoritarian rule and often discriminatory social practices. But culture flourishes in spite of such obstacles: religion continues to reinforce community; gender relations are slowly changing, as is representation in government; healthcare and education are improving; and the region’s historical sites, films, and sporting events continue to attract international attention.

What else shapes everyday life in the region?

Here are ten features and trends that define the experiences of many Middle Easterners and North Africans—in both positive and negative ways.

1. Home to Muslims, Christians, and Jews

For many residents of the Middle East and North Africa, religion is a source of great strength and social cohesion. The region is the birthplace of three major religions: Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. All three share a common origin and trace their roots back to the founding patriarch, Abraham. Today, there are around 2.3 billion Christians, 2 billion Muslims, and 15 million Jews around the world. Every year pilgrims visit the Middle East’s holy places, including the Church of the Nativity (believed to be Jesus’s birthplace) in Bethlehem and the Western Wall (a Jewish holy site) in Jerusalem. In 2024 , nearly two million Muslims traveled to Saudi Arabia for Hajj, a pilgrimage to the city of Mecca that Muslims are required to make at least once in their lives. Within Islam, two sects dominate—Sunnis and Shias. Although they share basic principles like a belief in the Quran (Islam’s holy book), they’ve built unique identities around their specific religious practices. Today, roughly 85 percent of the world’s Muslims are Sunni and about 10 percent are Shiite, with Muslims from smaller sects making up the remaining percentage.

2. A Wealth of World Historical Sites

There are over 90 UNESCO World Heritage sites across the Middle East and North Africa. These include ancient cities—some of the world’s oldest civilizations—like Babylon (in current day Iraq) and Thebes (Egypt). One of the most famous sites in the region is Petra, a city carved into tall pink sandstones. In 2023, over a million people visited Petra, which is located in Jordan. However, since the beginning of the conflict in Gaza, tourism has sharply declined. This trend highlights the close relationship between politics and regional economies. Alongside Mecca—and the Great Mosque that serves as the destination for the Hajj pilgrimage—the Middle East is also home to many other major religious sites. Perhaps the most historically symbolic (and, therefore, contested) site is the Old City of Jerusalem, which houses significant holy sites for Christianity, Islam, and Judaism alike.The city is divided along religious lines, which are sometimes fraught. Palestinians and Israeli police have repeatedly clashed at one of its most-venerated holy sites—known as the Temple Mount to Jews and the Haram al-Sharif to Muslims.

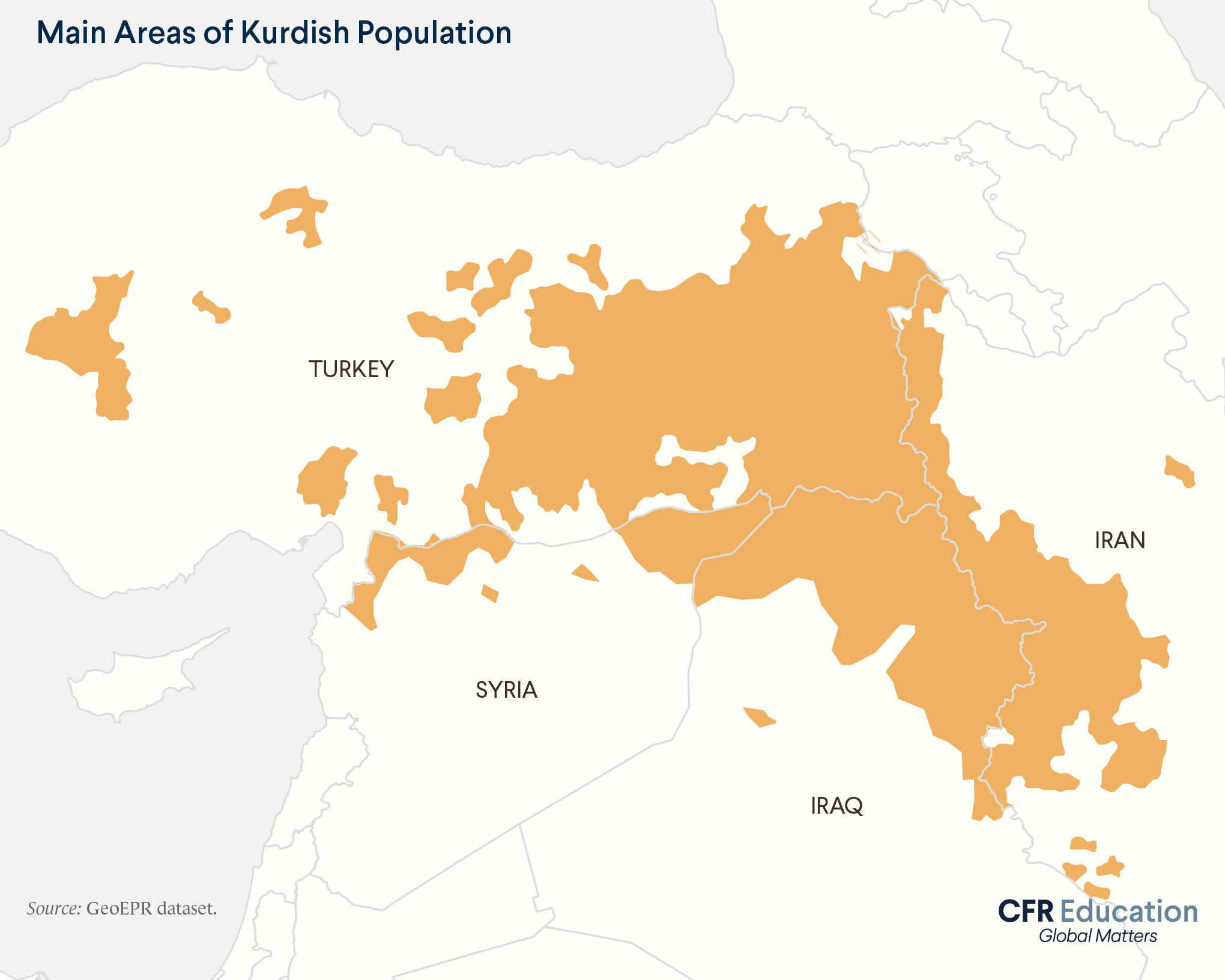

3. The Kurds: Enduring Oppression, Fighting for Self-Rule

Approximately thirty million Kurds—a predominantly Sunni ethnic group—live in Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. The Kurds form one of the world’s largest ethnic groups without a country. Since the end of World War I, they have been refused basic rights and freedoms such as the right to start Kurdish-language schools and newspapers. They have also been the target of state-sponsored violence. In Iraq in the 1980s, Saddam Hussein’s regime repeatedly used chemical weapons on Kurdish villages. In Turkey, the government frequently conducts raids and mass arrests in Kurdish-majority areas, targeting insurgents fighting for an independent Kurdistan. However, Kurdish political autonomy has grown across Iraq and Syria in recent decades. In 2017, Iraqi Kurds voted on independence while also battling the Islamic State. These self-governed regions still face outside interference. The now semi-autonomous Kurdistan Region in Iraq has complained of increasing influence from Baghdad, which in early 2024 reduced the number of its regional parliamentary seats.

4. Women Push Back Against Gender Disparity

Contemporary Middle Eastern societies have often been characterized by widespread social disparities and discriminatory laws—targeting women, ethnic minorities, and LGBTQ communities. Perhaps the most visible disparity is gender. In 2000, women made up only 3.5 percent of legislatures across the Arab world. In Saudi Arabia, women only received the right to vote and run for municipal office in 2015, and are still subject to guardianship laws requiring male permission to marry. In Iran, women continue to face crackdowns from “morality police” who have reportedly beaten women for refusing to follow headscarf laws. But attitudes, laws, and representation are all shifting; oppression is not the only gender story for the region. In 2023, women made up nearly 17 percent of Arab legislatures, up nearly 14 percent from 2000. Across the Middle East and across age groups, men are showing increasingly tolerant views of women holding political office. In 2021, Tunisia’s Bochra Belhaj Hmida became the Arab world’s first female prime minister. And in 2023, women made up over 50 percent of Bahrain’s public sector workforce, demonstrating strides in a country seeking gender parity.

5. Millions Flee Conflict—and Soon Climate Change

Recent conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa have caused millions to flee their homes. As of early 2023, over 16 million people are internally displaced within the region. That means the Middle East and North Africa contain almost a quarter of the world’s internally displaced persons (IDPs). Many other displaced persons have crossed borders into neighboring countries. Jordan, a country of 11 million people, hosts more than 700,000 refugees from Iraq, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. Jordan is also home to 2.3 million Palestinian refugees from the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and the 1967 Six Day War—the vast majority of whom are now Jordanian citizens. As of 2023, one in five people in Jordan is Palestinian. Aside from conflict, another factor predicted to increase displacement is climate change. The region is heating up almost twice as fast as the rest of the world. Water scarcity and declining crops are believed to further increase migration, as many leave in search of better conditions. In short: migration will continue to define the experience of millions living in the region.

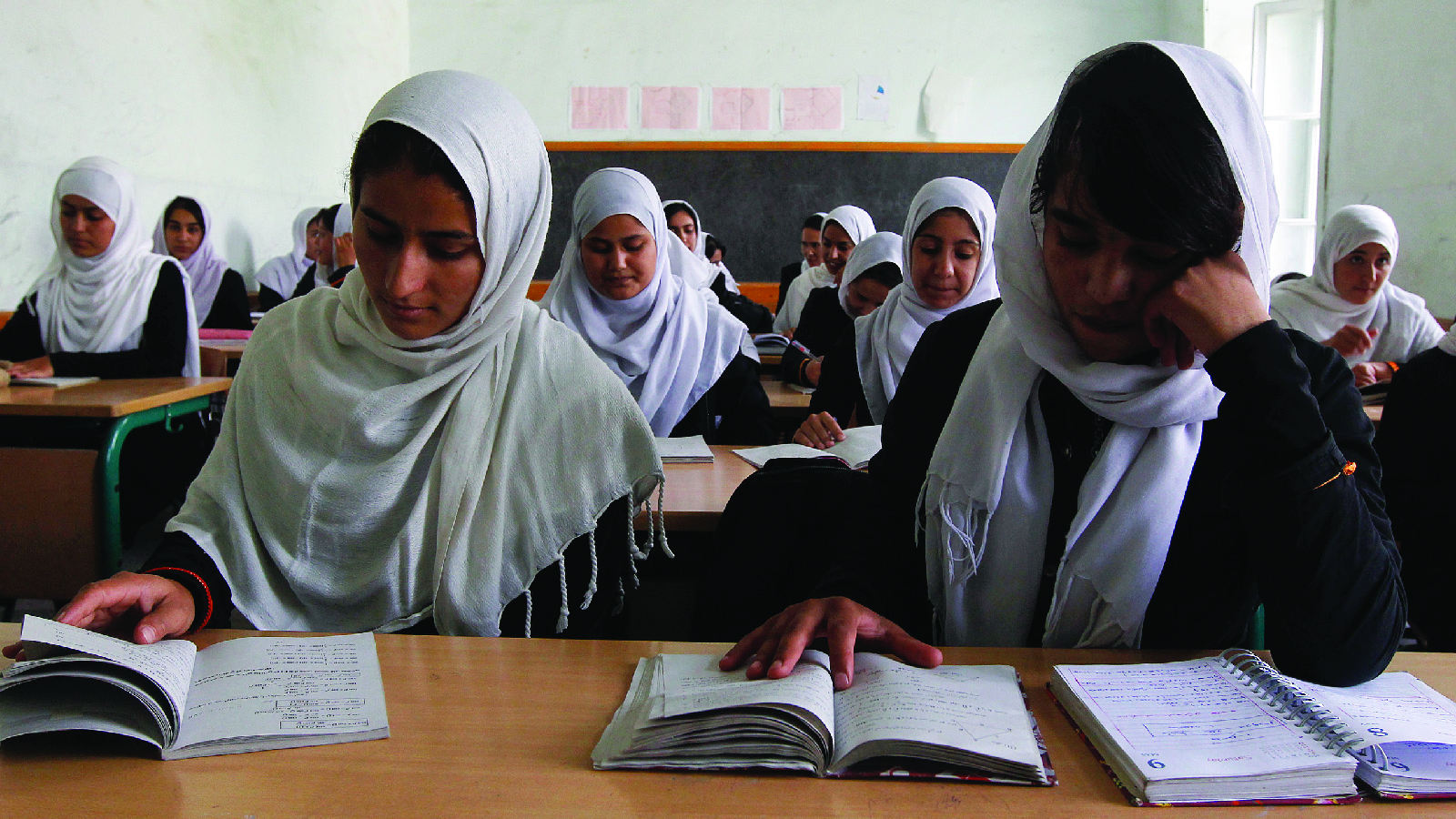

6. Education Is Expanding

School enrollment rates in the Middle East have soared over the past fifty years. Over the last decade, students were nearly three times as likely to be in secondary school (high school) and nearly eight times as likely to be in tertiary school (university, college, trade school) compared to 1970. Across developing countries in the Middle East and North Africa, there are also more women than men now enrolled in university programs. However, the region struggles to translate high enrollment into high female participation in the workforce. Women make up less than a quarter of the region’s workforce, despite their educational attainment. (This issue has been called the “MENA paradox.”) Recent challenges, including the Covid-19 pandemic, the 2023 earthquakes in Syria and Turkey, and ongoing conflicts in the region, have also disrupted education. In response, some countries are investing more in digital learning. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) launched the Digital School in order to reach vulnerable groups across the Arab world, including refugees. Another UAE initiative is the Arab Reading Challenge. The initiative, which promotes literacy, had more than 28 million students in 2024.

7. Health Outcomes Improve, But New Challenges Emerge

The Middle East has made dramatic improvements in its health outcomes over the last fifty years. Life expectancy has increased by over twenty-two years and is now higher than the global average. Maternal mortality rates have similarly improved, dropping to just one quarter of the global average. These health gains coincide with the Middle East’s economic development and an overall reduction in the region’s poverty rates. However, the region faces new health challenges. The Middle East, for example, has the world’s highest rates of diabetes, with total incidences projected to double over the next twenty-five years. And obesity—particularly among women—is yet another concern. In countries like Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, rates are higher than 40 percent.

8. Egypt: The Hollywood of the Middle East

Egyptian cinema goes all the way back to 1896—with a series of short French films. The country later became the Arab world’s major entertainment hub, making its first feature-length film in 1927. In the following decades, Egyptian movies and musicals made their way across the Middle East and North Africa. Many viewers began to mimic the Egyptian dialects of singers and movie stars. Egypt’s movies didn’t shy away from potentially controversial topics. Even under former dictator Hosni Mubarak, Egyptian films depicted topics like police brutality and homosexuality. However, since Mubarak’s removal during the 2011 Arab Uprisings, Egyptian film and TV has become increasingly censored and controlled by the new government. Now other countries are vying for entertainment influence, including Jordan, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia. As part of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 economic project, the Kingdom has pledged to invest $64 billion in domestic entertainment by 2028—hoping to be the Arab world’s new film and TV center.

9. The Gulf, a Region Fueled by Migrant Workers

Behind the creation of the Gulf’s megacities is a massive workforce of predominantly South Asian migrant workers who frequently face exploitative and unsafe working conditions. Millions of Bangladeshis, Filipinos, Indians, Nepalese, and Pakistanis work in the Gulf, where migrant workers comprise a large percentage of the domestic workforce—over 90 percent in some Gulf countries. In several countries they form a majority of the total population. Qatari citizens, for example, comprise just 12 percent of their country’s population; migrant workers make up over 70 percent. Migrant workers travel to the region in search of higher-paying jobs and sending remittances back to their homes. But in what is known as the kafala (“sponsorship”) system, low-skilled migrant workers in the Gulf require local sponsors to oversee their visa and legal status. This often results in exploitation, where employers deprive vulnerable migrant workers of their passports, trapping them in dangerous and underpaid (or entirely unpaid) labor. As Qatar prepared to host the 2022 World Cup, these abuses reached international attention. Qatar then instituted some reforms, including a minimum wage.

10. The Middle East Hosts Major World Events

Despite controversies leading up to the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, the tournament proved to be a regional success. That event brought in close to 1 percent of Qatar’s GDP. Other countries in the region also benefited from the added tourism. And the World Cup was only the beginning. The Middle East’s sports industry is expected to grow by nearly 9 percent by 2026 through investments in sports like Formula 1, golf, football, and esports. (Saudi Arabia is the big spender here, investing $2.3 billion alone in international football in 2022.) Alongside sports, the region is also hosting more international music festivals. Dubai and Saudi Arabia attract hundreds of thousands of visitors each year to festivals like MDLBEAST Soundstorm, the region’s biggest, which takes place in Riyadh.