Economics: The Americas

The economic landscape of the Americas is dominated by the United States, which accounts for nearly a third of the region’s billion-plus population and three-quarters of its economic output.

The economic landscape of the Americas is dominated by the United States, which accounts for nearly a third of the region’s billion-plus population and three-quarters of its economic output. Farther south, Latin America experienced significant economic growth over the last twenty years, but there is room for improvement: most economies still rely on commodities, like soybeans and oil, that are vulnerable to shifts in global prices. And with the major exception of the United States, Canada, and Mexico, which have been economically integrated since the 1990s, intra-regional trade still lags behind other regions.

U.S. Economy Dominates Region

In the Americas, the United States is the dominant economic power. Worth more than $20 trillion, the U.S. economy is the world’s largest and accounts for roughly a quarter of global gross domestic product (GDP). The services sector—such as the finance and insurance industry, technology and media firms, and health care companies—dominates the U.S. economy, making up 77 percent of its GDP, a characteristic shared by another regional economic heavyweight: Canada. Canada’s economy specializes in mining and manufacturing as well as services, making its economy more diverse. The United States outpaces the region’s second biggest economy, Brazil, by $19 trillion. This outsize role makes the United States a critical market for Latin American countries. Eleven of Latin America’s twenty countries have signed free trade agreements with the United States, and around 45 percent of the region’s total exports go to the United States.

Latin American Economies Trapped in the Middle

Economists consider much of Latin America to be stuck in the “middle income trap”—a term used to describe countries that experience promising economic growth but at unsustainable levels, leaving them unable to reach high-income status. In the 2000s, a commodity price boom, a surge of remittances (money sent by family members living and working abroad), and access to foreign financing helped fuel economic growth in some of Latin America’s biggest countries, such as Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Colombia, and Peru. But their economies haven’t shifted from commodities and manufacturing to more service-oriented industries. Unable to compete with poor economies in manufactured goods or with wealthier economies in innovation, many Latin American countries are trapped in the middle, with average incomes per capita of roughly $1,000–$12,000 per year. Latin America has seen its per capita income relative to the United States decrease continuously from 1960 to 2005. To make the transition to high-income status, experts say middle-income countries need to invest in education and vocational training, improve governance, reduce gender gaps, and diversify their economies instead of relying on just a few types of products.

Economic Inequality Affects Latin America

Latin America is the world’s most unequal region: just 10 percent of its population controls 71 percent of the region’s wealth. Even Chile, often hailed as an economic success, suffers from rampant inequality. The country’s consistently high economic growth masks the fact that this wealth is largely concentrated in the hands of a small percentage of the population. Experts trace Chile’s inequality back to years of economic policies that slashed government spending on public education and health care and privatized basic services like water distribution and social security. These policies were part of an economic model called the Washington Consensus, which incentivized privatization and free trade after a previous inward-looking model called import substitution industrialization failed to create long-lasting regional development. In 2019, frustration over this inequality manifested in countrywide protests following the government’s increase in subway fares. While prices rose by the equivalent of only a few cents, Chileans expressed outrage at the hike, which came amid low wages and high living costs, leaving many Chileans living paycheck to paycheck.

Latin America’s Risky Reliance on Commodities

Latin America is home to abundant natural resources, including much of the world’s forests and oil reserves. Consequently, half of the countries in Latin America and the Caribbean rely on exports of commodities like soybeans, coffee, oil, iron ore, and copper. During the early 2000s, the sale of these commodities to China, in particular, helped fuel Latin America’s rapid economic growth and an expanding middle class in countries like Brazil. But an overreliance on commodities or on a single industry (as opposed to developing a diverse economy like that of the United States), can be dangerous, akin to governments putting all of their proverbial eggs in one basket. When the price of a commodity crashes, it can bring down an entire economy along with it. Venezuela, for example, depends on oil sales, which make up 95 percent of the country’s export revenues. Starting in 2014, a combination of unstable oil prices and government mismanagement created a severe economic crisis, as Venezuela essentially lost its sole source of income. And a future crisis could be looming: the United Nations warns the region’s biggest economy, Brazil, could lose 70 percent of its largest export, soybeans, by 2050 if it doesn’t adapt to a changing climate.

Little Trade Among Latin American Neighbors

With the exception of the United States, Canada, and Mexico, countries in the Americas do not trade much with each other. Quotas and bans limiting certain imports and poor infrastructure slowing delivery of exports present challenges to intra-regional Latin American trade. Regions that prioritize intra-regional trade are considered to be more economically efficient (saving money by taking advantage of nearby markets) and, politically, more peaceful and cooperative (in order to trade, countries need to communicate). In East Asia, for example, intra-regional trade has proven a source of growth: as regional integration has increased, so have global exports and incomes. Latin America created trade blocs with hopes of achieving similar results, notably Mercosur (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Venezuela), which was hampered in the 1990s and early 2000s by members’ financial challenges, and the more recent Pacific Alliance (Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru). But in 2017, just 17 percent of Latin America’s exports went to other countries in the region. (In East Asia, meanwhile, the rate is about 50 percent.)

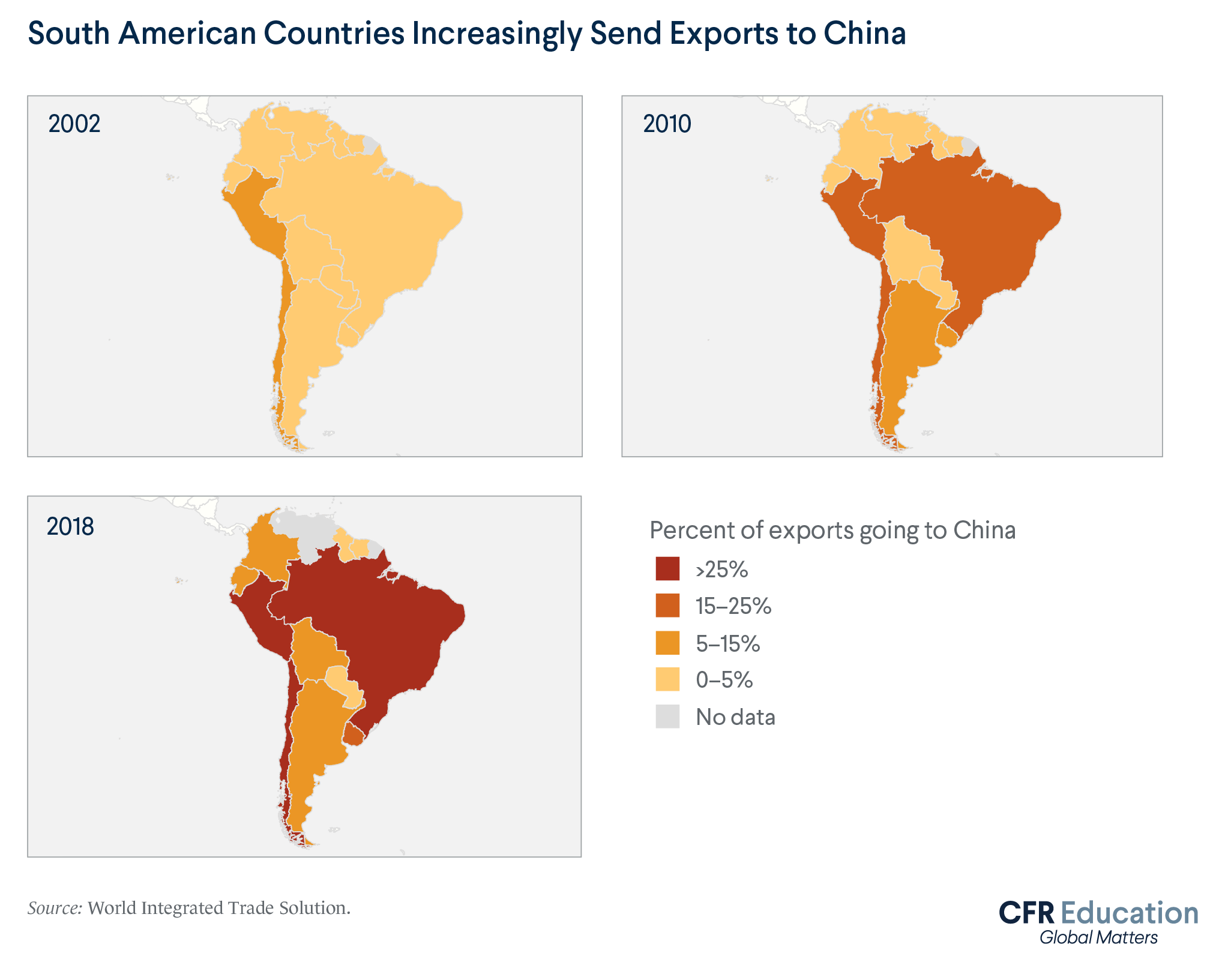

China’s Economy Looms Large

The United States has long been the top trading partner for many countries across the Americas, but its influence in the region is no longer unrivaled as China becomes increasingly important. China is now Latin America’s second-biggest trading partner, exchanging over $307 billion with the region in 2018. Brazil, Latin America’s largest economy, trades most with China, and several others, such as Chile, Peru, and Uruguay, are following suit. In fact, over the past ten years, Chinese trade with Latin America and the Caribbean has more than doubled as China imports oil, soybeans, copper, and iron ore to fuel its continued growth and rapid industrialization. Some experts warn that China’s demand for these types of commodities discourages Latin American countries from diversifying their exports—exposing their economies to risk.

Climate Change Reshapes Latin America’s Economies

Many Latin American countries whose economies depend on agriculture and tourism are particularly threatened by effects of climate change, such as more frequent floods, droughts, and rising sea levels. If global temperatures increase by 4 degrees Celsius by 2050, Latin American and Caribbean countries like the Bahamas (80 percent of which is within one meter of sea level) could face $22 billion in damages from coastal flooding. In addition to challenges, however, climate change presents economic opportunities. By 2040, the market for low–carbon emission (green) investments in Latin America and the Carribean will be worth $1 trillion—and some countries are already adopting practices designed to be more sustainable, environmentally and financially. Between 2010 and 2016, Uruguay invested $7 billion in energy infrastructure, and now produces around 97 percent of its electricity from renewable sources. Costa Rica, which produces 99 percent of its electricity from renewable sources, also converted 26 percent of its territory to natural reserves, protecting the country’s biodiversity while creating an ecotourism industry that generates $3.8 billion a year.

Global Pandemic Wreaks Havoc on Latin America’s Economy

In addition to the enormous public health toll, COVID-19 is fueling the worst economic downturn in Latin America’s history. The crisis has paralyzed global supply chains, forcing the closure of factories, such as automobile manufacturers, that are unable to acquire essential parts. With factories shuttered and global demand down, regional exports are on track to fall by as much as 23 percent in 2020. In addition, the global pandemic is grinding the Caribbean’s vital tourism industry to a standstill. And with the public health crisis driving unemployment worldwide, remittances—the money migrants send home from working jobs abroad—are projected to fall by 10 to 15 percent in 2020. Together, these challenges exacerbate years of economic difficulties in the region, including slowing growth and mounting public debt, and could contribute to sixteen million people in Latin America falling into extreme poverty.