U.S. Foreign Policy: Europe

In his 1796 farewell address, President George Washington cautioned the United States to steer clear of foreign entanglements.

In his 1796 farewell address, President George Washington cautioned the United States to steer clear of foreign entanglements. Until the twentieth century, U.S. policymakers mostly honored this advice, staying out of Europe’s conflicts both on the continent and in its colonies around the world. Even after joining World War I and decisively turning the tide, the United States bolted back across the Atlantic soon after a peace agreement was signed. But that tendency changed with World War II, the largest mobilization of U.S. military service members in the country’s history. The United States emerged from the war as a superpower with global interests, and invested heavily in the security and economic prosperity of Europe. No longer an isolationist country, the United States would go on to forge deep and lasting ties with Europe. And as World War II gave way to the Cold War, foreign entanglements—with Europe and around the world—became the norm.

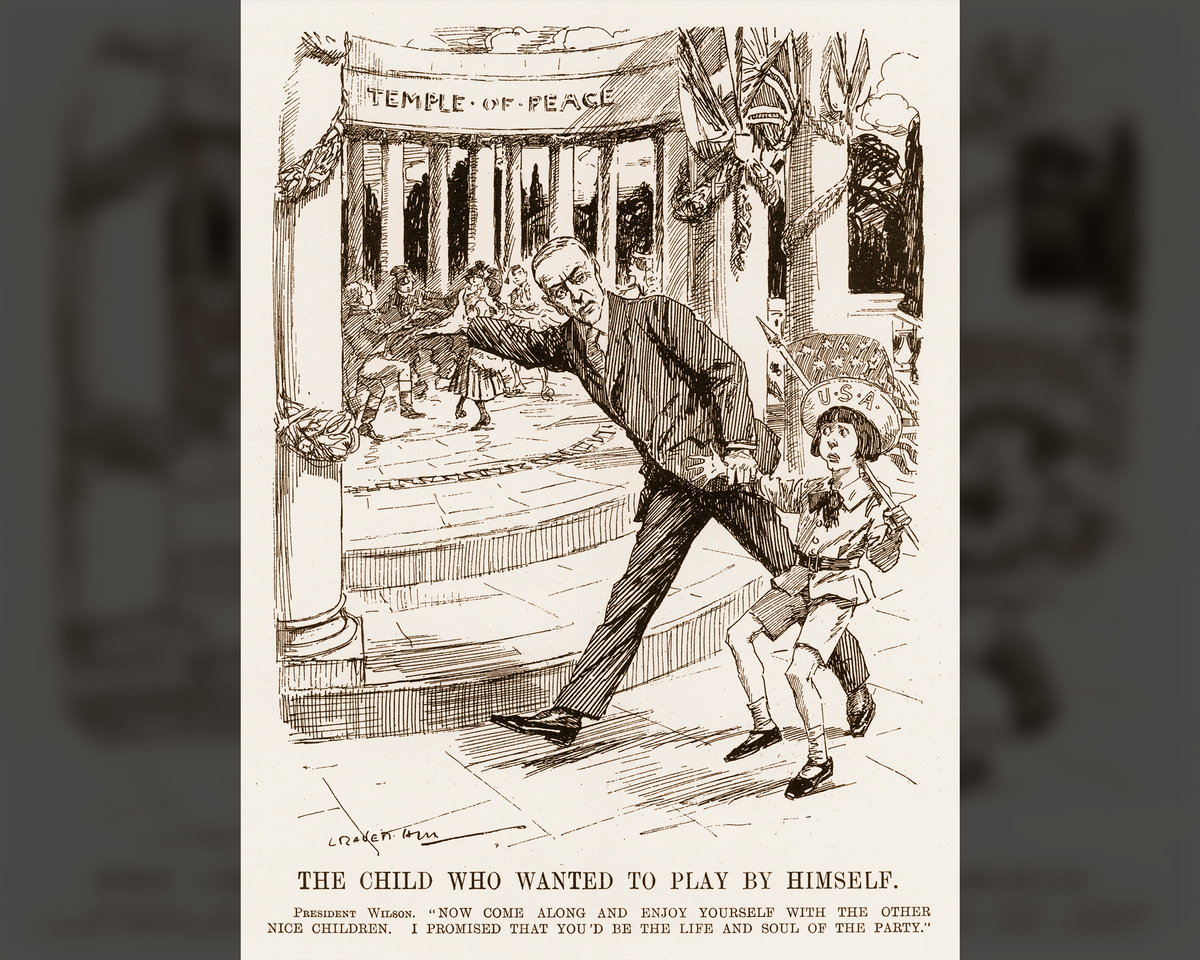

Early Attempts at International Cooperation Are Abandoned

The United States largely stayed out of European conflicts until the final two years of World War I. President Woodrow Wilson framed his decision to declare war against Germany—after years of careful neutrality—as a critical investment in world peace. The United States needed to have a seat at the peace talks to help shape the postwar international order. In 1918, Wilson outlined an idealistic vision in his Fourteen Points speech: imperialism would be dismantled and colonies would have a path to self-determination—the idea that people have the right to choose their own government. Most importantly, disputes would be resolved by a new international organization, the League of Nations. Later that year, as the first sitting U.S. president to visit Europe, Wilson attended the Versailles peace talks brimming with bold ideas. Wilson succeeded in creating the League of Nations (the precursor to the United Nations), but he was unsuccessful in securing U.S. membership in the organization. Congress voted against joining, and the United States retreated into isolationism. Without universal membership or effective enforcement measures, the league failed, and Europe was soon at war, again.

From Isolationism to Engagement: The Rise of the U.S.-Europe Partnership

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, the United States, wary of getting embroiled in another overseas conflict and still grappling with the Great Depression, opted to remain on the sidelines. According to a 1940 poll, just 7 percent of Americans supported the country entering the war on the side of the Allies (France, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom), but secretly, the United States had been sending military weapons and equipment to the United Kingdom as part of the Lend-Lease policy. On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, pushing the country into World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt condemned it as “a date which will live in infamy;” it was also a day that launched the United States’ decades-long involvement on the European continent.

U.S. Intervention Shifts Tide of World War II

By the end of 1941, Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany was well on the way to victory in World War II. Germany and Italy—two of the Axis powers, along with Japan—controlled most of continental Europe. France had surrendered after just six weeks of fighting the Germans. The Soviet Union, which had previously signed a nonaggression pact with Germany, was caught completely off guard when Germany invaded it earlier that year. Britain found itself almost alone, and vastly outnumbered. But when the first U.S. troops landed in Europe the very next year, the tide began to shift against the Axis powers, as Germany found itself caught in between a Soviet counteroffensive on its eastern front, and a decisive U.S. offensive in the west. By the war’s end, some sixteen million Americans would serve in Europe and the Pacific, making World War II the largest mobilization of U.S. military service members in the country’s history. It also came at a tremendous cost. More than four hundred thousand American service members died in the fight against the Axis powers —a death toll greater than all of the United States’ other overseas wars combined. When Nazi Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, the United States stood victorious and in a powerful position to direct Europe’s post-war future.

How Containment Came to Define U.S. Cold War Strategy

With Nazi Germany defeated, the United States set its sights on a new adversary: the Soviet Union. Led by Joseph Stalin, the Soviet Union began supporting communist governments across Eastern Europe in the aftermath of World War II. Soon, however, the threat of Soviet influence became clear—a direct challenge to the United States and its promotion of democratic, capitalist governments. On the heels of a devastating world war, the United States faced a dilemma: Should it directly confront the powerful Soviet Union and risk another major conflict, or should it look the other way, potentially allowing communism to spread? Instead, the United States opted for a third approach, containment. This strategy sought to maintain a balance of power between the United States and the Soviet Union but pledged to confront the Soviets when that balance was threatened, especially in areas geopolitically important to the United States. Containment would become the basis of U.S. strategy throughout the Cold War and was used to justify U.S. interventions across Europe and around the world.

Rebuilding Europe and Containing Communism Through the Marshall Plan

World War II devastated Europe, displacing fifty million people as fighting destroyed entire cities. The United States, meanwhile, emerged as a global power. This time, instead of retreating across the Atlantic as it did following World War I, it worked to prop Europe back up. In 1947, U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall announced a multibillion-dollar plan to provide aid to any European country trying to rebuild its economy. But the Marshall Plan was not merely charity; it was a cornerstone of U.S. Cold War strategy. The United States believed that Europe’s physical, economic, and political collapse made it vulnerable to encroaching Soviet influence. In providing aid, the United States sought to shore up its democratic allies. Sure enough, each of the sixteen Western European countries that accepted funds from the $13-billion-Marshall Plan (more than $130 billion in today’s dollars) experienced rapid economic recovery and deepened relations with the United States. The Soviet Union and Eastern European countries, on the other hand, rejected the aid, fearing it would give the United States influence over their economies.

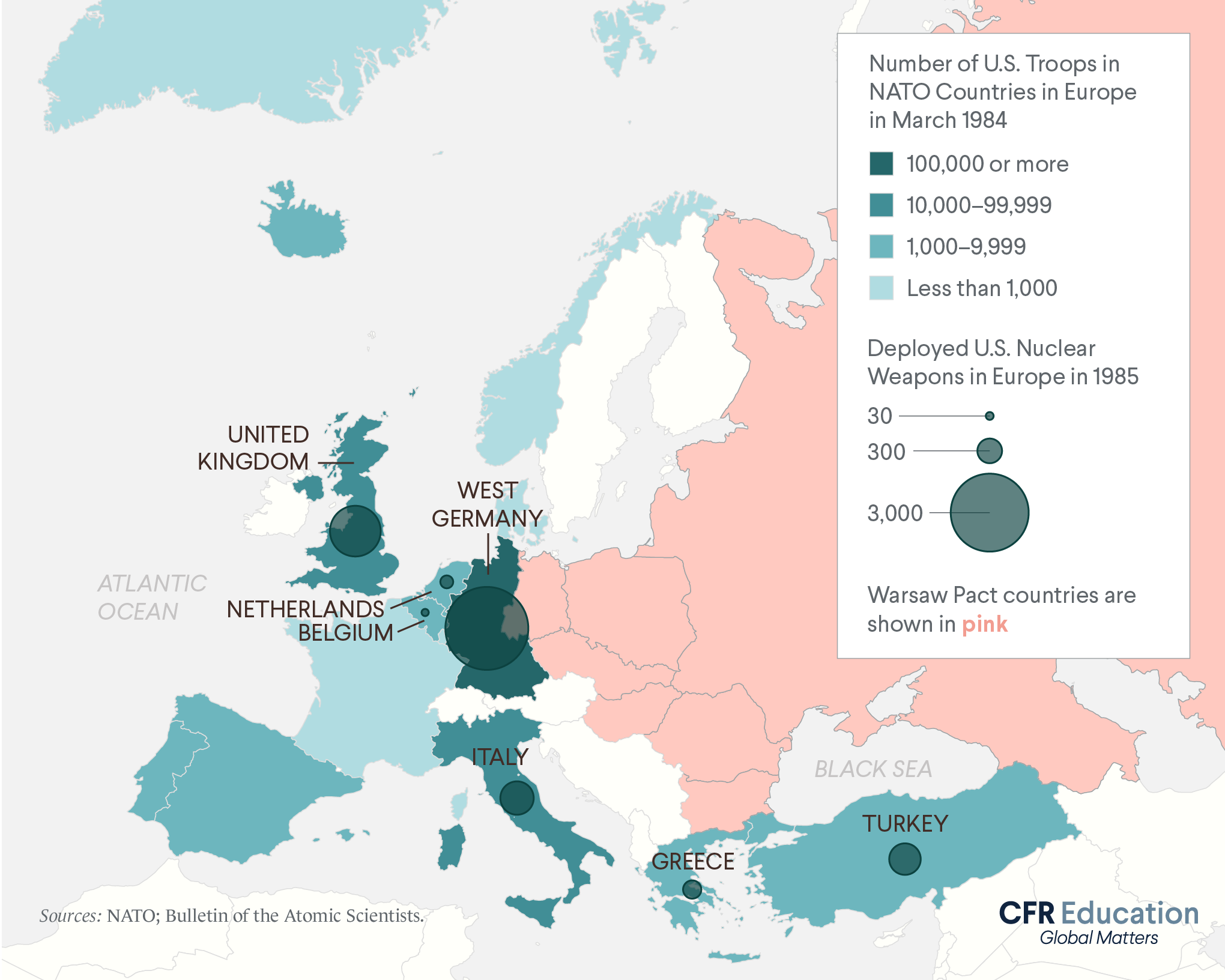

An Unprecedented Alliance: The North Atlantic Treaty Organization

In addition to rebuilding Western Europe’s economies, the United States helped ensure the region’s security following World War II. In particular, the United States feared the Soviet Union’s growing military presence in Europe following a 1948 revolution in Czechoslovakia, which installed a communist government on Germany’s border. In response, the United States agreed to provide military assistance to rebuild Western Europe’s armies, and in 1949 the United States, Canada, and ten European countries formed a military alliance known as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The cornerstone of this alliance was mutual security, the pledge that an attack on one country would be treated as an attack on all. This groundbreaking peacetime alliance made the United States—with its outsized military strength—effectively the defender of Western Europe. During the Cold War, the United States stationed more than four hundred thousand troops throughout Europe along with missiles positioned to strike Moscow. Despite tensions that occasionally flared, the Cold War stayed mostly cold in Europe, with NATO and the threat of nuclear war effectively deterring armed conflict on the continent.

Proxy Fights Define U.S.-Soviet Cold War Relationship

The Cold War effectively divided the world into three distinct camps. The First World (also known as the Western Bloc) consisted of the United States, Western Europe, and its capitalist allies. The Second World (also known as the Eastern Bloc) comprised the Soviet Union and friendly communist and socialist countries. Finally, the Third World represented the countries that sought to remain neutral throughout the great power struggle, though some were pulled in. While the United States and the Soviet Union never directly fought during the Cold War, the two rivals engaged in proxy conflicts throughout much of the Third World. In Latin America, Africa, and East Asia, U.S. policymakers acted on the belief that a country falling to communism would cause a ripple effect among its neighbors. Known as the domino theory, this was the main argument justifying the United States’ costliest Cold War engagement—the Vietnam War, waged for twenty years as officials feared the spread of communism in Cambodia, Laos, and across Southeast Asia.

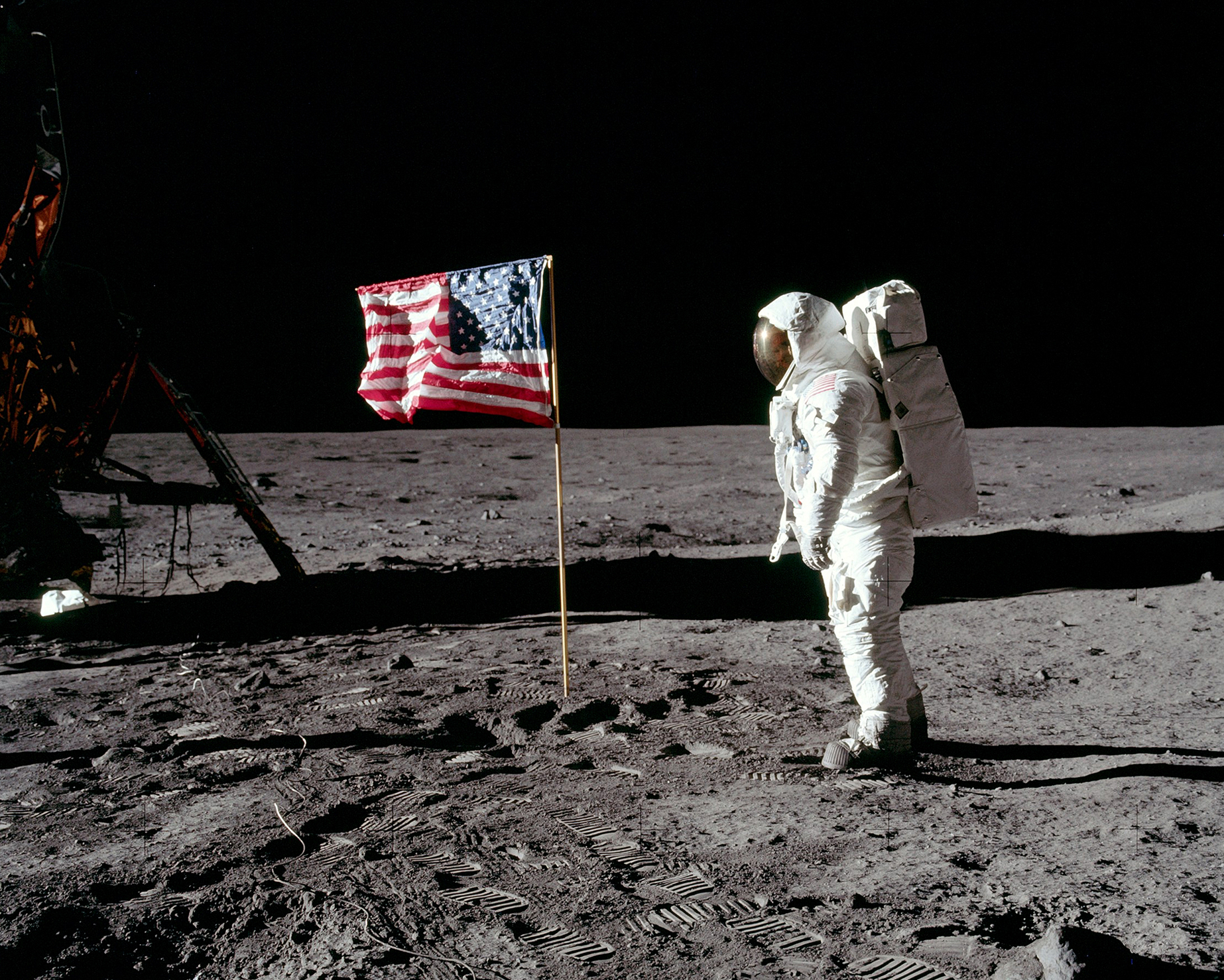

To Win War of Narratives, Cold War Goes to Space

The Cold War was not just a war of weapons; it was also a war of narratives. In arts, culture, science, and sports, the two superpowers used their soft power to convince the world of their superiority. Hollywood, the Olympics, even chess competitions became cultural battlefields for the United States and the Soviet Union. But arguably the Cold War’s highest-profile soft power competition occurred in outer space. The so-called space race, which lasted from the 1950s through the early 1970s, saw the two superpowers competing for a series of milestones: which would be the first to launch a satellite, send a man into orbit, or walk on the moon. (Answers: the Soviets in 1957, the Soviets in 1961, and the Americans in 1969.) The 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing was the most-watched event in television history at its time (more than five hundred million people tuned in around the world), and was a major soft power victory for the United States.

From Brief Détente, Agreements Emerge

Starting in the late 1960s, a decade-long thawing of the Cold War, known as détente, led to some productive agreements. The nuclear arms race was taking an economic toll on the United States and the Soviet Union, and, geopolitically, both were weakened: the Soviets had lost their alliance with powerful Communist China, and the United States was still mired in the Vietnam War. Amid these circumstances, the two sides agreed to a series of treaties aimed at stopping the spread and development of nuclear weapons technology, and in 1975, signed the Helsinki Final Act, along with thirty-three European countries. Since the 1950s, the Soviets had been seeking recognition of post–World War II borders; this agreement delivered that, in exchange for guarantees from the Soviets on human rights and free flow of information. But by the end of the 1970s, détente was breaking down: the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, and arms control talks stalled.

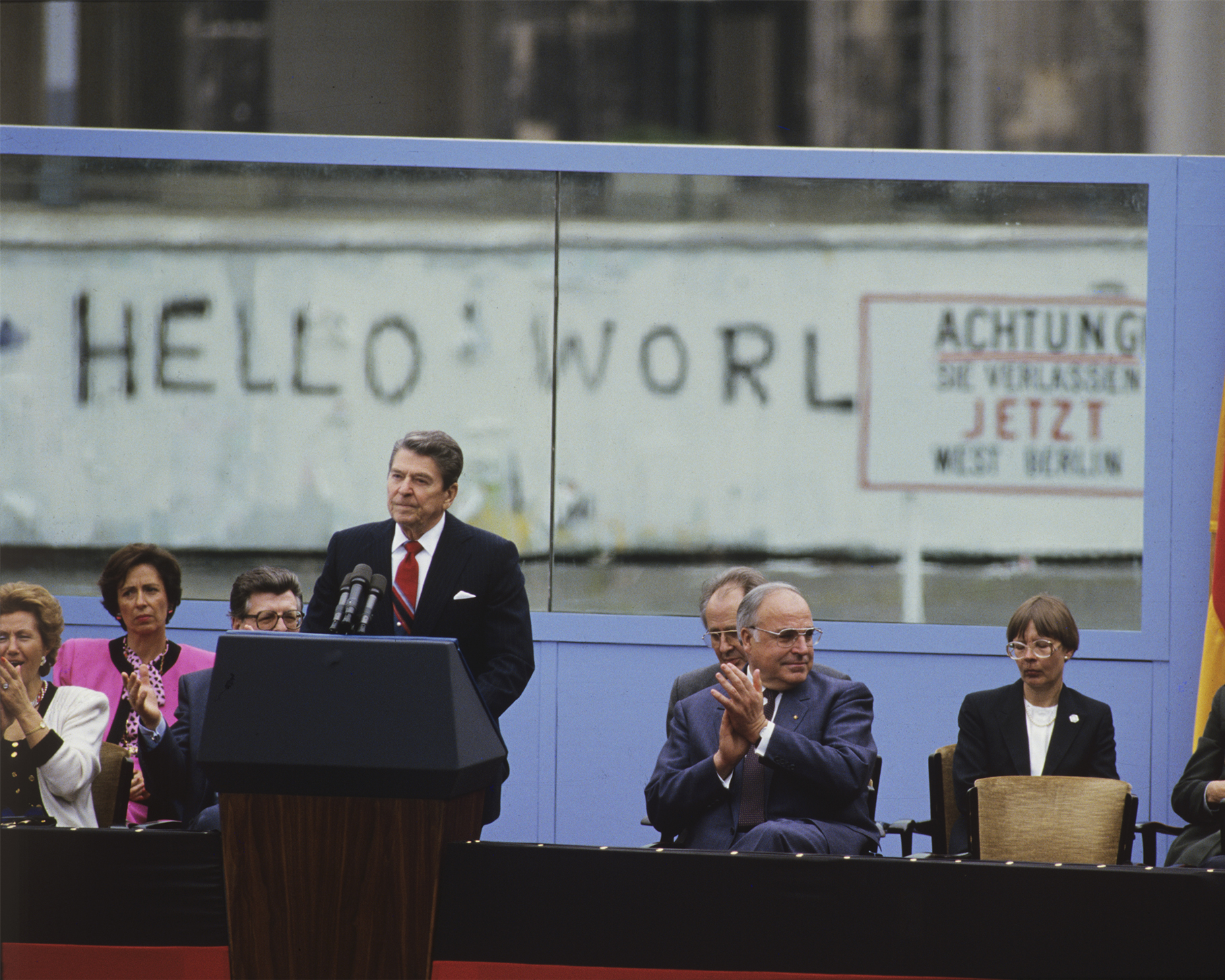

U.S. Pressure Contributes to End of Cold War

Experts debate which factors brought about the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Internally, Moscow was grappling with an economy in freefall, growing unrest throughout its satellite states, and an ineffective bureaucracy. At the same time, U.S. foreign policy of the 1980s sought to place added pressure on Moscow. Going beyond containment, President Ronald Reagan pledged to take on the Soviets more directly. Through the so-called Reagan doctrine, the United States armed anti-communist guerrillas and resistance movements in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Concurrently, the Reagan administration ramped up America’s military budget. Reagan also kept open diplomatic lines with his Soviet counterpart, Mikhail Gorbachev, perhaps most famously exhorting him to “tear down” the Berlin Wall, which separated communist East Berlin from democratic West Berlin. Soon after the wall fell in 1989, Germany reunified, the Soviet Union dissolved without incident, and the United States emerged as the world’s sole superpower.

Iraq War Exposes Divisions in Atlantic Partnership

In the 1990s, NATO members joined the United States in its military campaign in the former Yugoslavia. And after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, NATO joined the United States in the war in Afghanistan—the only time the collective defense pledge of the North Atlantic Treaty, known as Article 5, has been invoked. But when the United States invaded Iraq in 2003 on the grounds that Iraqi President Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction, the move divided the Atlantic alliance. Some countries such as Poland and the United Kingdom sent troops to help with the occupation of Iraq. Meanwhile, France and Germany led a political coalition that opposed the intervention, with France threatening to veto the United States’ efforts at the United Nations. The European public overwhelmingly opposed the war; just 7 percent of French and 10 percent of British people supported joining the United States without UN approval.

Tense Alliance Between Turkey and United States

The United States’ most fraught relationship with a NATO ally is with Turkey—a country strategically situated at the crossroads of Asia and Europe. Since the end of the Cold War, the United States had hoped that Turkey would serve as a model of a liberal, Muslim democracy for the Middle East, but that aspiration never materialized. Under the presidency of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey has become increasingly authoritarian, as dissidents are arrested, newspapers are shut down, and independent courts are suspended. At the same time, Turkey is warming up to Russia; it even purchased a missile defense system from Russia to the sharp rebuke of the United States. And, in Syria, Turkey and the United States have nearly come to blows over their opposing treatment of Kurdish forces. Relations between Turkey and the United States have deteriorated so much that in 2019 President Donald J. Trump threatened to “devastate Turkey economically” over their disagreements in Syria—an unprecedented threat against a NATO ally.

Return to Rivalry: U.S.-Russia Relations Deteriorate in Post-Cold War Era

In 1992, just after the Cold War ended, 66 percent of Americans held a favorable view of Russia. Over the next few years, the United States sent economic advisors and billions of dollars in aid to Russia to help restructure its economy, and the two countries signed landmark arms control agreements. But in less than twenty years, this optimism disappeared, as the United States and Russia once again returned to open rivalry. Not all experts agree over what changed. Some point to President Vladimir Putin’s stoking of anti-Western sentiments, particularly as the country’s economy collapsed in the late 1990s. Others suggest that Russia bristled at NATO’s enlargement and the perceived humiliation of the former Soviet superpower by the West. What is clear is that relations today are at a low point. In 2008 and 2014, the United States sanctioned Russia after it invaded Georgia and annexed the Ukrainian territory of Crimea. In 2016, Russia directly interfered in the United States’ presidential election, prompting even more sanctions. And, today, the two countries are returning to old, Cold War–like patterns of backing opposing sides in conflicts around the world in countries like Syria and Venezuela.

Questioning U.S.-Europe Alliance in Age of Trump

Since the end of World War II, one basic principle has shaped U.S. foreign policy: strong alliances enhance the United States’ power around the world. In turn, U.S. presidents since the 1940s have all sought to cultivate close relationships with allies in Europe—countries like France, Germany, and the United Kingdom—that share the United States’ outlook on democracy and world order. But, under the Donald J. Trump administration, the value of the U.S.-Europe partnership is being seriously questioned. Trump has publicly attacked America’s closest allies, derided countries for not contributing enough to NATO, and even considered withdrawing the United States from the alliance altogether. Meanwhile, he has warmed up to authoritarian politicians in Hungary, Poland, and Russia. While the United States has long believed that a strong, democratic Europe is in its own interest, the country may now be returning to its post–World War I isolationist tendencies by questioning such decades-long alliances.