History of U.S. Immigration Policy

Explore how the United States has responded to migrants throughout history—from the Chinese Exclusion Act to DACA—and how immigration policy influences the society, economy, and politics of a country.

Immigration in the United States has contributed significantly to the country’s social, political, and economic growth. The United States makes an interesting case study for immigration policy, since many Americans can trace their lineage to migrants who were pushed from their home countries—fleeing persecution or conflict, or brought by force in the case of many enslaved people.

Throughout U.S. history, different factors—economic conditions, national security, and elements of societal discrimination—have all guided U.S. officials’ decision-making on immigration policy.

In today’s political climate, immigration remains a vibrant political debate, shaped particularly by differing viewpoints regarding the policies that should govern the U.S. southern border. Those debates are rooted in a history of evolving approaches to immigration policy.

One reason the issue is such a flashpoint in the United States is that the country is home to more immigrants than any other nation in the world. More than eighty-six million people immigrated to the United States between 1783 and 2019.Those immigrants have contributed to the economic and social fabric of the United States—a country revered by many for serving as a “melting pot” for different nationalities and cultures.

But what have been some of the policies shaping those massive waves of immigration over time? Looking at nineteenth-century history and tracking U.S. immigration policies over time makes policies proposed by today’s elected leaders easier to understand and evaluate.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

A nineteenth-century U.S. immigration policy demonstrates the pitfalls of early immigration policy based on ethnicity and nationality.

This early U.S. policy completely suspended immigration from a single country: China. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act banned Chinese people from immigrating to the United States for ten years and prohibited Chinese immigrants already in the country from becoming citizens. Further caps on Chinese migration to the United States were imposed in 1892.

Why was the United States targeting immigrants from China? A combination of social discrimination and economic factors contributed to the policy.

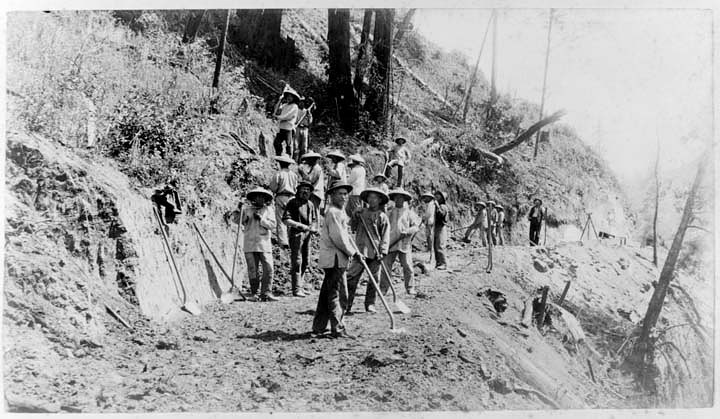

An economic downturn in China, driven by the Opium Wars with Great Britain and crop failures, matched with economic opportunities in the American Gold Rush, resulted in an influx of Chinese immigration to the United States in the 1850s. Over three hundred thousand people of Chinese origin immigrated to the United States from 1850 to 1882. Chinese laborers, who accounted for up to 90 percent of the workforce of one of the transcontinental rail companies and faced a growing onslaught of racism, were instrumental to the construction of the U.S. railway system, a source of national pride. Despite the fact that those immigrants were relatively small in number, politicians pressured lawmakers to restrict their arrival in 1852. Discrimination against Chinese immigrants skyrocketed, with American laborers resenting added competition from Chinese laborers who would accept lower pay.

The Chinese Exclusion Act, which resulted from those social and economic pressures, was the first time the United States restricted entry based on nationality and ethnicity. The act was repealed after World War II, along with all similar laws. But even after its repeal, lingering anti-Chinese sentiment drove continued caps on Chinese migration, such as the Magnuson Act which limited the number of Chinese immigrants at 105 after the war. These restrictions continued despite China serving as a U.S. ally in the war.

The Johnson-Reed Act of 1924

This policy extended immigration bans on people from Asia and set quotas on immigrants from other countries. The act, driven in part by further strains of xenophobia (or, prejudice against people of a particular nationality) in the United States, limited immigration based on established nationalities marked by the 1890 U.S. census. It enabled more west Europeans and British immigrants to enter the United States, while discriminating against those from Eastern and Southern Europe and excluding Asians completely. One author of the act, Senator David Reed, said after the act’s passing, “The racial composition of America at the present time thus is made permanent.” The act persisted until 1965 when President Lyndon B. Johnson passed the Hart-Celler Act, abolishing the ethnicity-based quota system.

The Bracero Program of 1942

During World War II, the U.S. government made significant changes to its immigration policies. In 1942, Executive Order 9066 stripped Japanese Americans of their rights and placed them in internment camps under the specter of growing U.S.-Japan distrust and conflict. At the same time, the government created the Bracero program, which recruited Mexican immigrants for agricultural labor. Inspired by an increased demand for workers before World War II, it ended in 1964, after over four million braceros (“laborers,” in Spanish) had worked in agriculture and on railroads in the United States.

Even during the Bracero program’s existence, mass deportations of undocumented Mexican workers occurred. As many as 1.3 million people were removed from the country soon after being recruited to work in the United States.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (Hart-Celler Act)

The most recent major policy affecting immigration today began in 1965. After eighty-three years of nationality-based immigration policy, the Immigration Act of 1965 set the foundation for modern immigration. Although some changes, such as the 1990 Immigration Act which placed a limit on green-cards which grant permanent residency, have been put into place, policy has otherwise remained fairly unchanged.

Enacted under President Lyndon B. Johnson, the 1965 Hart-Celler Act eliminated the previous immigration policy based on national origins. It capped visas, or permission to legally enter the United States, at 290,000 per year, or 20,000 per country per year. The policy opened the door to non-European immigrants in unprecedented numbers. Aiming to break from the past racial and ethnic divisions, President Johnson hoped the act would “repair a very deep and painful flaw in the fabric of American justice”—and it quickly transformed the ethnic makeup of U.S. society. By 1980, most U.S. immigrants came not from Europe but from Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Contemporary Immigration Policy: 2012 DACA and beyond

Debates continue as to what contemporary policies could deal appropriately with changes in the international economic and political landscape.

Although the Hart-Celler Act of 1965 continues to shape approaches to immigration policies by driving how visas are allocated, it does not cover other issues such as surges in illegal immigration and the protection of vulnerable populations. As immigration to the United States has expanded, so has the number of undocumented immigrants to the country who are seeking opportunity.

Debates continue as to the best immigration reforms to address those populations’ needs. In the absence of revamped legislation, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy of 2012 protects eligible immigrants who came to the United States when they were children from deportation and grants them the ability to work in the United States. DACA has protected more than eight hundred thousand young people, known as DREAMers (DREAM stands for Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors), who entered the United States without formal visas as children.