Contemporary History World at War: Introduction

Essential Events Between 1900 and 1945

Learn how two world wars and other major historical developments from the Spanish-American War to World War II reshaped global affairs in the first half of the twentieth century.

Last Updated

October 21, 2022

World History Timeline: 1898–1945

1898

1898

1898

Spanish-American War Signals Growing U.S. Ambition on World Stage

1905

Spanish-American War Signals Growing U.S. Ambition on World Stage

1905

Japan Gains International Reputation With Victory in Russo-Japanese War

1906

Japan Gains International Reputation With Victory in Russo-Japanese War

1906

Launch of HMS Dreadnought Sparks Arms Race

Jun 28, 1914

Launch of HMS Dreadnought Sparks Arms Race

Jun 28, 1914

Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand Ignites World War I

Aug 15, 1914

Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand Ignites World War I

Aug 15, 1914

Panama Canal Transforms U.S. and Global Economy

Apr 1, 1915

- May 31, 1915

Panama Canal Transforms U.S. and Global Economy

Apr 1, 1915

- May 31, 1915

Second Battle of Ypres Introduces World to Large-Scale Chemical Warfare

May 16, 1916

Second Battle of Ypres Introduces World to Large-Scale Chemical Warfare

May 16, 1916

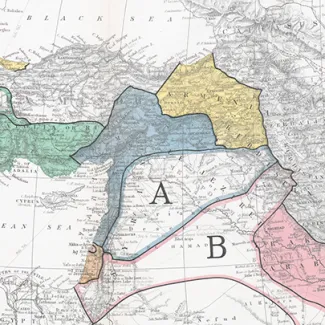

Sykes-Picot Agreement Leads to Ottoman Empire Break Up

Jan 1, 1917

Sykes-Picot Agreement Leads to Ottoman Empire Break Up

Jan 1, 1917

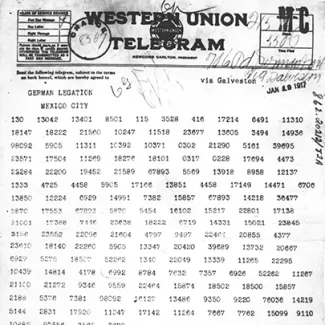

Zimmerman Telegram Helps to Push United States into World War I

Nov 7, 1917

Zimmerman Telegram Helps to Push United States into World War I

Nov 7, 1917

Bolshevik Revolution Leads to Birth of Soviet Union

1917

- 1920

Bolshevik Revolution Leads to Birth of Soviet Union

1917

- 1920

World War I Influences Suffrage Movement Successes

Nov 11, 1918

World War I Influences Suffrage Movement Successes

Nov 11, 1918

Armistice Day Marks Close of ‘War to End All Wars’

Jan 12, 1919

Armistice Day Marks Close of ‘War to End All Wars’

Jan 12, 1919

Paris Peace Conference Leads to League of Nations, Embittered Germany

1929

- 1939

Paris Peace Conference Leads to League of Nations, Embittered Germany

1929

- 1939

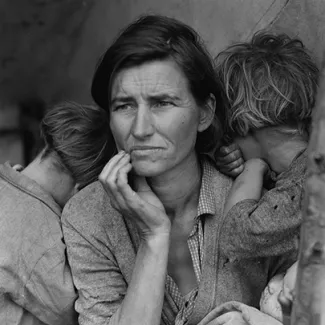

Great Depression Creates Pre-Conditions for World War II

Sep 18, 1931

Great Depression Creates Pre-Conditions for World War II

Sep 18, 1931

Invasion of Manchuria Signals Japanese Expansion

Jan 30, 1933

Invasion of Manchuria Signals Japanese Expansion

Jan 30, 1933

Hitler Named Chancellor as German Economic Situation Worsens

Oct 3, 1935

Hitler Named Chancellor as German Economic Situation Worsens

Oct 3, 1935

Second Italo-Ethiopian War Demonstrates League of Nations’ Ineffectiveness

1936

Second Italo-Ethiopian War Demonstrates League of Nations’ Ineffectiveness

1936

Spanish Civil War Provides Dress Rehearsal for World War II

Sep 1, 1938

Spanish Civil War Provides Dress Rehearsal for World War II

Sep 1, 1938

Britain, France Appease Aggressive Germany at Munich Conference

May 1, 1940

- Jun 1, 1941

Britain, France Appease Aggressive Germany at Munich Conference

May 1, 1940

- Jun 1, 1941

With Eastern Europe Occupied, Nazis Decimate Western Europe

1941

- 1945

With Eastern Europe Occupied, Nazis Decimate Western Europe

1941

- 1945

The Holocaust—Nazi Germany’s Systematic Mass Murder Campaign

Dec 7, 1941

The Holocaust—Nazi Germany’s Systematic Mass Murder Campaign

Dec 7, 1941

Japan’s Attack on Pearl Harbor Brings United States Into World War II

Jul 1, 1942

- Feb 1, 1943

Japan’s Attack on Pearl Harbor Brings United States Into World War II

Jul 1, 1942

- Feb 1, 1943

Battle of Stalingrad Signals Beginning of End for Germany

Aug 1, 1942

- Feb 1, 1943

Battle of Stalingrad Signals Beginning of End for Germany

Aug 1, 1942

- Feb 1, 1943

Battle of Guadalcanal a Turning Point in Pacific

Jun 6, 1944

Battle of Guadalcanal a Turning Point in Pacific

Jun 6, 1944

Invasion of Normandy Begins World War II’s Final Act

Aug 1, 1945

Invasion of Normandy Begins World War II’s Final Act

Aug 1, 1945

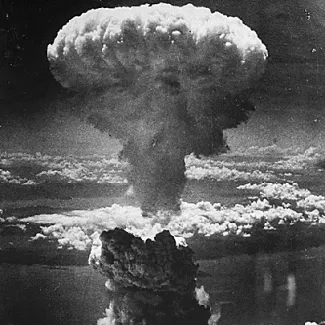

Atomic Bombs Bring World War II to an End

Atomic Bombs Bring World War II to an End

Aug 1, 1945