Economics: Europe and Eurasia

As in other regions, certain European countries belong to an economic or customs union—a “single market”—that makes trade between its members seamless.

As in other regions, certain European countries belong to an economic or customs union—a “single market”—that makes trade between its members seamless. Unique to Europe, however, is the eurozone, a monetary union in which all members use the same currency. The eurozone is contained within the European Union (EU); most, but not all, EU members use the euro. The eurozone functioned well initially but faced deep challenges after the 2008 financial crisis, when countries were left with limited tools to fix their own economic problems. Understanding what integration means for countries in and out of the eurozone is critical to understanding Europe’s economy today.

Europe’s Economy Towers, but Challenges Persist

At almost $19 trillion, the gross domestic product (GDP) of the EU is the second highest in the world, behind only the United States. Germany is by far Europe’s biggest economy, accounting for more than a fifth of the EU’s economic output. It is an industrial powerhouse—particularly in automotive, mechanical engineering, and chemical and electrical industries—and the third largest exporting nation after China and the United States. But Germany and other large European economies, like France, Italy, and the United Kingdom, face obstacles, as global challenges (like trade tensions and years-long uncertainty surrounding Brexit) have combined with domestic ones (political instability in Italy) to limit their economic growth.

Europe’s Inequality Breaks Down Along Geographic Lines

While Europe is economically strong overall, a stark income gap exists across the continent: EU countries enjoy higher standards of living than most of their non-EU neighbors. Broadly, this translates into an East-West divide. The average EU resident makes more than $36,000 per year (more than three times the global average). By contrast, in Europe’s poorest country, Ukraine (which is not in the EU), residents make just $3,000 per year. Unemployment also varies widely, and tends to follow a North-South division. Germany’s unemployment rate is under 4 percent, compared to nearly 20 percent in Greece. Youth unemployment is an even more pronounced challenge. In Greece, youth unemployment rates reached a sky-high peak of 60 percent in 2013. Italy and Spain’s rates are both above 30 percent. (For context, U.S. unemployment rate during the Great Depression maxed out at 25 percent.)

Understanding the Euro

If you have traveled around Europe before, it’s likely you used just one currency—the euro. But that wasn’t always the case. Just twenty years ago, you would need pesetas for Spain, francs for France, and deutsche mark for Germany. But today, nineteen European countries use the euro, and with a couple of exceptions, countries that join the EU are legally obligated to adopt the currency. Before they can do so, however, they need to prove their economies are viable according to convergence criteria. Some countries, like the United Kingdom and Denmark, opted out of the eurozone from the beginning, because they were unwilling to cede their sovereignty of economic policy-making. The euro, the culmination of economic integration, presents risks and rewards beyond mere EU membership: common currency brings collective strength, but economic woes in one country can quickly spread to the whole eurozone.

Trade-Offs of the Eurozone

When the euro works, its benefits are widespread. A common currency allows weaker countries to borrow money at similar rates as stronger economies (that is, more cheaply). Because the euro is so widely used, it is considered a safe bet, which lowers interest rates and encourages foreign investment. But with shared benefits come shared risks: in exchange for a stronger currency, countries must accept decreased autonomy. The eurozone crisis, which began in 2010 after the global financial crisis, required wealthier countries, like Germany, to compensate for less well-off members, like Greece. In exchange for adopting austerity measures (cutting government spending on welfare and pensions), Greece received a series of bailouts from the European Union. Both countries ended up believing they were worse off: Germans resented bailing out their struggling (or, in their view, fiscally irresponsible) southern neighbors, while Greeks resented being directed (or, in their view, bullied) by powerful Germany to accept major spending cuts its citizens did not vote for.

Strength in Numbers: The Power of EU’s Collective Trade Policy

As an economic bloc, the European Union offers its twenty-eight member countries the collective strength that their national economies alone could not have had individually. Take a look at international trade: the EU has a single foreign trade policy, with the goal of increasing trade both within Europe and internationally. From its founding in 1999 to 2010, EU foreign trade doubled; in 2018, the EU countries together were the top export market for the United States. This collective power allows the EU to set the global agenda on trade-related issues, including data privacy, environmental protection, sustainable development, and human rights standards.

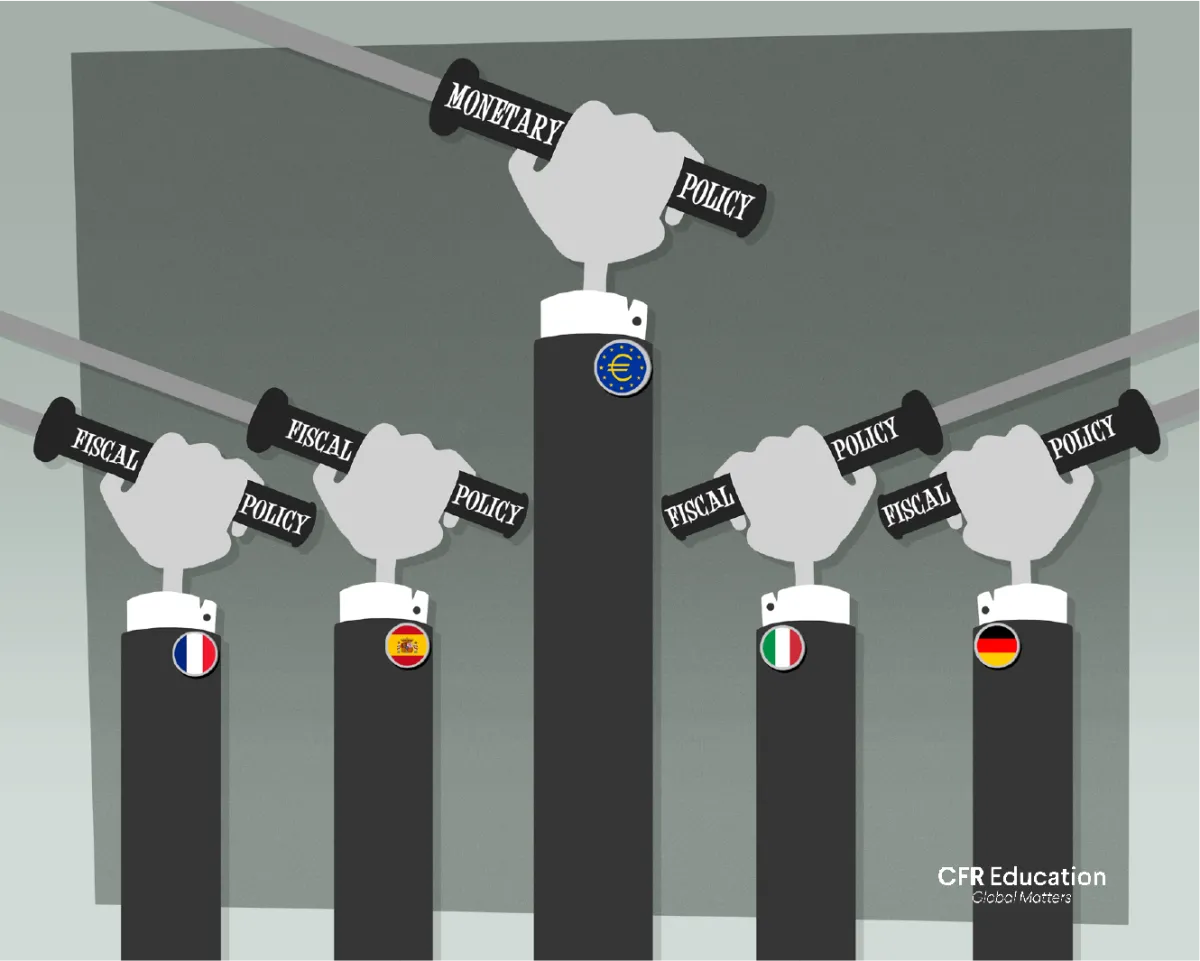

One Monetary Policy, Nineteen Fiscal Policies...What Could Go Wrong?

The eurozone is a monetary union, but not a fiscal union, meaning countries in the eurozone lack control over their own monetary policies (setting interest rates and controlling the amount of money in circulation). Instead, the European Central Bank (ECB) sets a single eurozone interest rate and controls the money supply. The nineteen eurozone countries, meanwhile, control their own fiscal policies (taxes and government spending). The mismatch between what levers governments or national central banks can pull, and which ones the ECB can, was blamed for prolonging the eurozone crisis. When the recession hit the United Kingdom, which opted out of the euro, its central bank was free to act in its own national interest, and increased the amount of money in circulation to help alleviate the crisis. But in the eurozone, the ECB hesitated to act, leaving countries with only fiscal policy options, like increasing taxes and cutting spending.

Italy’s Budget Fight With EU Highlights Future Challenges

While the eurozone crisis is largely over, Italy’s economy (the EU’s fourth-largest) is smaller today than it was before the crisis hit in 2008. With high debt and towering unemployment, Italy’s struggling economy is a major cause for concern in Brussels. In June 2018, a populist government took power in Italy, with a platform of “taking back control of its borders and its economy.” The new government blamed Brussels for stifling its economy with strict rules, like capping Italy’s debt, and created a massive budget to fund its campaign promises. The EU rejected the budget, prompting a game of chicken, which the EU ultimately won. The populist government may have folded in this round, but twenty years after adopting the euro, Italy’s economy has never really reformed to become more like Germany’s. As a result, experts questioning the sustainability of the eurozone often cite Italy’s precarious economic situation.

Economic Crisis Brings Opportunity for Greater Integration

When COVID-19 spread throughout the European Union (EU) in 2020, governments responded by closing borders, imposing national quarantines, and shutting down factories to curb transmission of the deadly virus. Experts projected the economic fallout from these measures would plunge the EU into its deepest recession since its formation in 1993 and reduce its GDP by a staggering 7.4 percent in 2020. Many of the hardest-hit south European economies—notably Italy and Spain—called on the EU to provide emergency relief funding. However, several north European countries—including Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden (also known as the EU’s frugal four)—argued that they should not be responsible for bailing out their southern neighbors, much like during the 2010 eurozone crisis. With the EU highly divided, France and Germany—its two largest economies—proposed a breakthrough EU recovery fund in May 2020. The final deal not only provides much-needed relief to European countries reeling from the economic, political, and public health crises of COVID-19 but also make Europe more integrated than ever before.