Why Did World War II Happen?

In this free resource on World War II, understand the causes of World War II and why these issues drove countries back to battle just two decades after World War I.

When World War I ended in 1918, the last thing people wanted was an even greater conflict. So why did the world return to combat just two decades later to fight World War II?

Granted, Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939 triggered declarations of war from France and the United Kingdom, formally starting World War II. But that event was only the final straw in a series of events. Various other economic and political challenges had been building up tension for years.

This resource examines the era between World Wars I and II—also known as the interwar period—breaking down those issues that set the stage for the world’s second and far deadlier global conflict.

The Treaty of Versailles

In 1919, representatives from more than two dozen countries gathered in France to draft peace treaties that would set the terms for the end of World War I. However, in a break with tradition, those on the losing end of the conflict were excluded from the conference. This particularly stirred resentment in Germany, the largest and most powerful defeated country.

Without German input, the victors—led by the United States, France, and the United Kingdom—decided what peace would look like after the conflict.

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson wanted to structure peace according to his framework for preventing future global conflicts. This framework, known as the Fourteen Points, advocated for the establishment of an international organization called the League of Nations. This multilateral governing body would be staked on the idea of collective security, meaning the invasion of one country would be treated like a threat to the entire group. Wilson’s Fourteen Points also called for arms reductions as well as free trade. Wilson further helped lay the groundwork for the principle of self-determination—the concept that groups of people united by common characteristics should be able to determine their political future.

Meanwhile, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, fearing a resurgent Germany on France’s border, prioritized a more punitive approach over peace.

Negotiations dragged on for months, but in the end, the Treaty of Versailles forced Germany to accept blame for the conflict, give up its overseas colonies and 13 percent of its European territory, limit the size of its army and navy, and pay reparations (financial damages) to the war’s winners.

Back home, Germans were incensed and staged protests over what they saw as harsh and humiliating terms. Nazi leader Adolf Hitler said the treaty was designed “to bring twenty million Germans to their deaths and to ruin the German nation.” One of the central tenets of the Nazi party was to undo the deal. This kind of campaign promise helped the Nazi Party gain followers prior to World War II.

The exact role of the peace agreement in dooming the world to another war is still hotly contested. But some observers at the time had doubts it would ensure an end to hostilities. Economist John Maynard Keynes quit his post with the British delegation to Versailles over the treaty. Keynes argued it was too punitive and would lead to catastrophe in Europe. And one French military leader predicted with alarming accuracy that the treaty did not represent peace but rather an “armistice for twenty years.”

The aftermath of World War I revealed that the way leaders make peace can be used as kindling for the future fires of war.

The Failed League of Nations

The League of Nations emerged from the Treaty of Versailles with thirty-two member countries. The League included most of the victors of World War I, and eventually expanded to include Germany and the other defeated nations. (Despite President Wilson’s ardent campaigning, the U.S. Senate rejected membership.) Under the organization’s founding agreement, these countries promised not to resort to war again.

The League was premised on the idea that security threats to one member demanded responses from all members. But when it came time to respond to those threats, the organization largely failed.

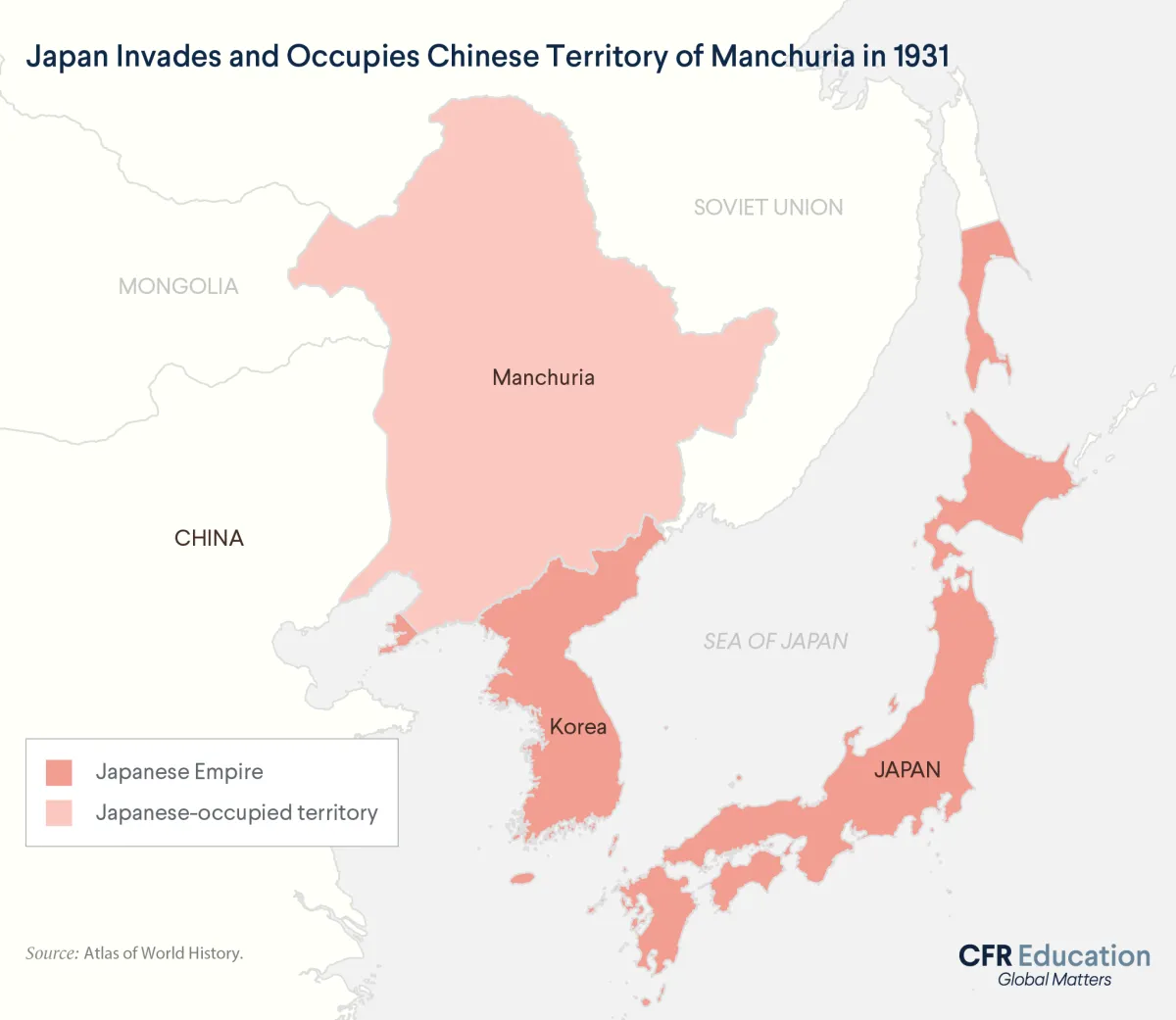

The League’s department for settling international disputes required unanimous agreement before taking action, which severely limited its ability to act. For example, after Japan invaded the Chinese region of Manchuria in 1931, the League was unable to act, given Japan’s veto power.

In 1935, Italy invaded Abyssinia (now Ethiopia), and, once again, the League’s response was minimal. In an urgent address to the organization, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie asked, “What have become of the promises made to me?”

The unrealistic optimism that helped doom the League also plagued international relations more widely at the time. For example, the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact obligated its signatories to resolve conflicts without resorting to violence. However, the pact was effectively meaningless, as countries like Germany, Italy, and Japan blew through international agreements meant to prohibit aggression and expansionism and countries such as France and the United Kingdom refused to act to preserve the balance of power.

Traumatized and weakened from the First World War, the League’s great powers proved not only unable to respond to these security threats but uninterested in addressing them. As a result, the group’s toothless response to blatant aggression only encouraged more invasions.

By the onset of World War II, the League had been effectively sidelined from international politics. Many experts believe its lack of U.S. membership doomed the organization from the start. Meanwhile, the withdrawal of other countries—Germany, Italy, and Japan had all left by 1937—also undermined the group’s credibility.

Though the League ultimately failed to prevent World War II, the organization made critical inroads on issues such as global health and arms control. Many of the group’s agencies and ideals carried over to its successor organization, the United Nations. But the challenges associated with collective security remain. Even amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the United Nations has struggled to take action due to disagreements among powerful member countries.

The Rise of Hitler

Germany’s road to the Second World War began near the end of the first, when it signed an armistice in November 1918. Although leaders on the frontlines saw the war was unwinnable, others refused to accept defeat.

A myth began to take hold that Germany could have won the war had it not been for unrest at home. This myth, promoted by conservatives and the military, falsely accused Jewish people and left-wing activists of stabbing the country’s war effort in the back. Some called members of the Weimar Republic—Germany’s new, democratic government—the “November criminals” and blamed them for Germany’s loss in World War I.

Then, back-to-back crises hit the German economy. In the early 1920s, the country experienced hyperinflation, a situation in which prices skyrocketed so quickly that German currency lost much of its value. Savings were suddenly worthless. By 1923, buying bread required a wheelbarrow for carrying bills.

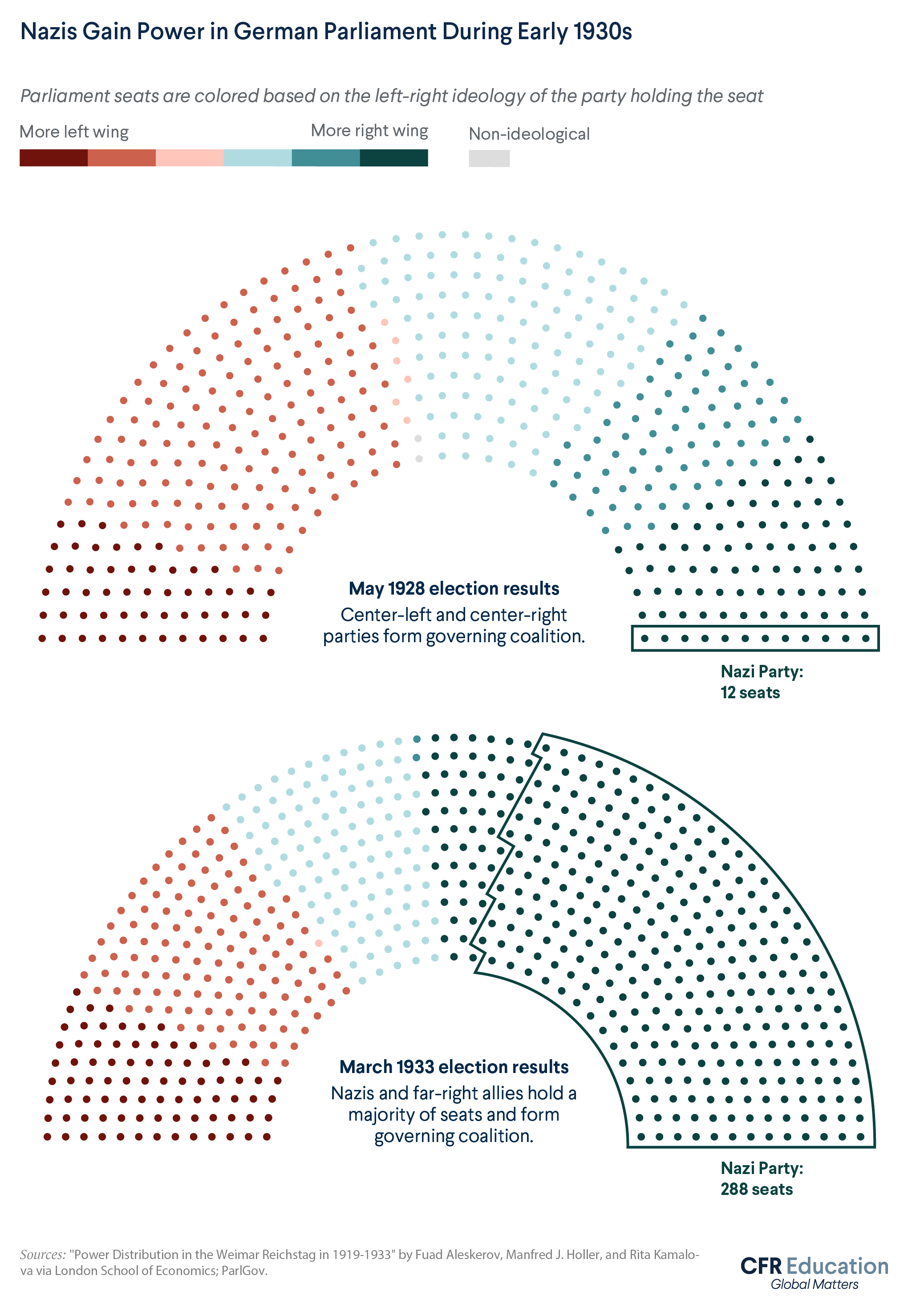

After a period of economic recovery—and a moment in which it seemed democracy could take hold in Germany—the Great Depression kicked off a new era of financial and political turmoil. Between 1929 and 1932, German unemployment skyrocketed nearly fivefold. Eventually a quarter of the labor force was unemployed. Against this backdrop, popular support for the Nazi party surged. Between parliamentary elections in 1928 and 1932, the party went from winning 3 percent of the vote to 37 percent—at which point support apparently peaked.

The Nazis promised to tear up the Treaty of Versailles, resurrect the economy, and restore German honor. They also sought to create a much larger, racially pure Germany. Under Nazi ideology, Germans were racially superior and entitled to greater territory or lebensraum (living space) in the east. When they ascended to power, the Nazis persecuted those they saw as inferior, including Jewish, Slavic, Black, and Roma people.

In 1933, German President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor of the government. Many of the political elite thought they could control him. Instead, Hitler quickly seized the reins of the country, centralizing power and suspending civil liberties. Germany’s short-lived experiment with democracy had failed.

As Germany’s absolute ruler, or führer, Hitler reintroduced conscription, or mandatory military service; rebuilt the country’s armed forces; ordered the genocide of millions; and invaded countries across Europe. Three-quarters of a century after his death, Hitler’s rise to power and Germany’s fall from democracy into fascism serve as frightening reminders of the dangers of racism and extremism in politics.

Japanese Imperialism

Japan’s 1941 aerial bombardment of the Pearl Harbor naval base in Hawaii brought the United States back into another global conflict. Though U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt called the strike a surprise attack, it did not come out of nowhere; rather, it grew from Japan’s ambitions for imperial power.

Frustrations had been building for decades in Japan over the country’s role in the world. In 1919, representatives from the country pushed for a statement affirming racial equality to be included in the Treaty of Versailles but were rejected. Discriminatory laws in several Western countries targeted Japanese immigration. And to many in Japan, the international system that emerged after World War I seemed designed to privilege Westerners’ access to wealth and resources.

Japan had long sought to accumulate imperial power. Taiwan became Japan’s first colony in 1895, and more territory followed. In 1931, Japan invaded China’s Manchuria. The territory provided Japan with a geographic buffer against Soviet communism. Manchuria also had an abundance of natural resources that the island nation desperately lacked. After provoking a war in 1937, the Japanese invaded huge parts of China to the south of Manchuria.

The invasion of Manchuria arguably marks the first salvo of the Second World War. Over the next decade, conflict escalated into outright war between Japan and China.

During the war, Japanese forces massacred military prisoners and civilians and committed widespread sexual violence. Up to twenty million Chinese people are estimated to have died between 1937 and 1945. These tactics and global condemnation over atrocities at the Rape of Nanjing sparked widespread outrage. However, it took years for Japan’s aggression to provoke international retaliation.

But Japan’s ascendancy and the conflict in Europe concerned Roosevelt. He instituted an embargo cutting Japan off from U.S. oil in response to the country’s expansionism. Japan’s navy had only about six months of oil in reserve. The country decided it was time for an offensive strategy toward Western targets, including at Pearl Harbor.

The United States declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941, one day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. On December 11, Germany and Italy (allies with Japan under the 1940 Tripartite Pact) retaliated by declaring war on the United States.

U.S. Isolationism

The United States of the 1920s and 1930s had, in many ways, turned inward. The mood back home was dour in the aftermath of the First World War. The conflict had taken so many lives, and the Great Depression had ruined the lives of many who survived. The country continued to play an active international role, especially in Latin America and the Caribbean. However, it mostly removed itself from the armed conflicts unfolding across Europe and Asia.

Against this backdrop, Congress enacted high, protectionist tariffs intended to shield American businesses from competition. These economic policies damaged relations between the United States and its trading partners. It also passed several Neutrality Acts aimed at ensuring the United States avoided foreign conflicts. (A decade prior, the Senate had rejected U.S. membership in the League of Nations for similar reasons.) Meanwhile, domestic resistance to President Roosevelt’s moves to support the Allies in the 1930s revealed to Germany and Japan that aggression had few downsides.

At the start of the 1940s, isolationism had strong support from a political organization called the America First Committee. The group had about eight hundred thousand members and a famous proponent—Charles Lindbergh, the first pilot to cross the Atlantic Ocean solo. The organization’s stated aim was to keep the United States out of the war, which began in Europe in 1939, but the group also served as a platform for racism and anti-Semitism.

Whether the United States could have helped prevent conflict through less isolationist economic and foreign policies is difficult to know. But the debate over the country’s role in international politics—and whether U.S. leaders should put “America First”—has continued into the present.

Appeasement

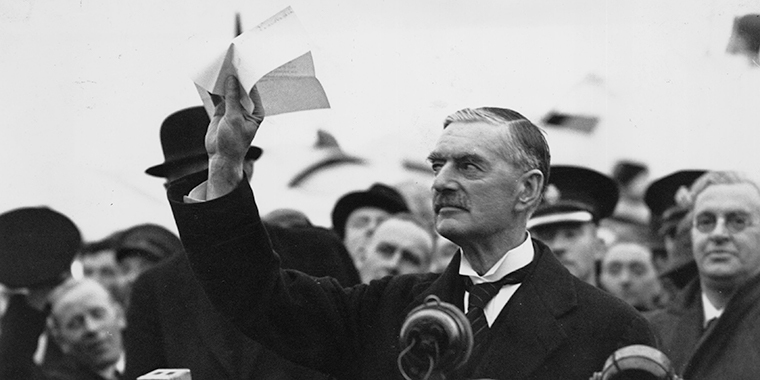

In the 1930s, France and the United Kingdom practiced a policy of appeasement toward Nazi Germany. This policy entailed tolerating German territorial aggression rather than confronting it with force. The hope was that German ambition would settle down peacefully. This policy reached its low point in the late summer of 1938 when Hitler threatened to drag Europe into war if the Sudetenland, a majority-German region in Czechoslovakia, was not awarded to Germany.

Just months earlier, Germany had annexed Austria in an event called the Anschluss. Hitler aimed to unite ethnic Germans across Europe under his rule. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain hoped Hitler would be satisfied after acquiring the Sudetenland. British and French leaders signed the Munich Agreement and accepted Hitler’s demands in exchange for a promise that Germany would make no further demands. When Chamberlain returned to London, he arrived with an agreement signed by Hitler. The pact affirmed “the desire of our two peoples never to go to war with one another again.” As a result, Chamberlain believed he held the means to “peace for our time.” Needless to say, that was not the case, as fighting erupted the following year.

But according to the dictator himself, an earlier challenge from the French could have spelled the end of his ambitions. In 1936, after remilitarizing the Rhineland—a region on Germany’s border with France—in violation of the Treaty of Versailles, Hitler reportedly said, “The forty-eight hours after the march into the Rhineland were the most nerve-wracking in my life. If the French had then marched into the Rhineland, we would have had to withdraw with our tails between our legs.”

In the decades since World War II, appeasement has been condemned as a disastrous foreign policy failure. Leaders have used and abused the term to justify (or deride) foreign intervention. But judgments of this strategy have the benefit of hindsight. When British and French leaders signed the Munich Agreement, they faced intense domestic pressure to avoid war. And though Chamberlain and others misjudged the massive scale of Hitler’s ambitions, it’s difficult to know whether more interventionist measures would have stopped him.

World War II was the deadliest conflict in human history.

World War II was the deadliest conflict in human history. And unlike World War I, which resulted in mostly military casualties, World War II saw civilian deaths outnumber soldier deaths three-to-one. High civilian death tolls reflected the rise of aerial warfare that made it possible to bomb faraway cities and towns.

Another uniquely horrifying aspect to the conflict was the Holocaust. During World War II, the Nazis advanced a state-sponsored and systematic campaign of murder and persecution against those deemed inferior or to be enemies based on factors like race and behavior. At least eleven million people were killed, including six million European Jews and five million others, including gay people, Romani, and people with disabilities, among others.

In total, forty-five million civilians died during World War II amid rampant mass killings, starvation, and disease.

World War II led to the creation of the world as it exists today. From the ashes of the conflict emerged the international system of institutions promoting free trade, human rights, and collective security. But it also introduced the potential for cataclysmic destruction, as it ushered in the era of nuclear weapons.

Was World War II inevitable?

It can be tempting to trace the causes of World War II back to one moment, such as Hitler’s invasion of Poland. But this moment only tells one part of the story. In reality, complex dynamics—including the rise of radical nationalism, U.S. isolationism, the failure to maintain a global balance of power, and misplaced optimism that World War I had been the war to end all wars—propelled countries around the world into combat.

Despite the simmering tensions around the globe at the time, World War II was not inevitable. It happened because people in power made decisions throughout the interwar period that helped set the fuse of conflict on fire. These decisions ultimately led to the explosive conflict. Evaluating the choices of policymakers is one of the benefits we have as students of history; and by studying them, we can learn how to avoid similar conflicts in the future.