Learn how the world’s nearly two hundred countries came to be and whether the map is set in stone.

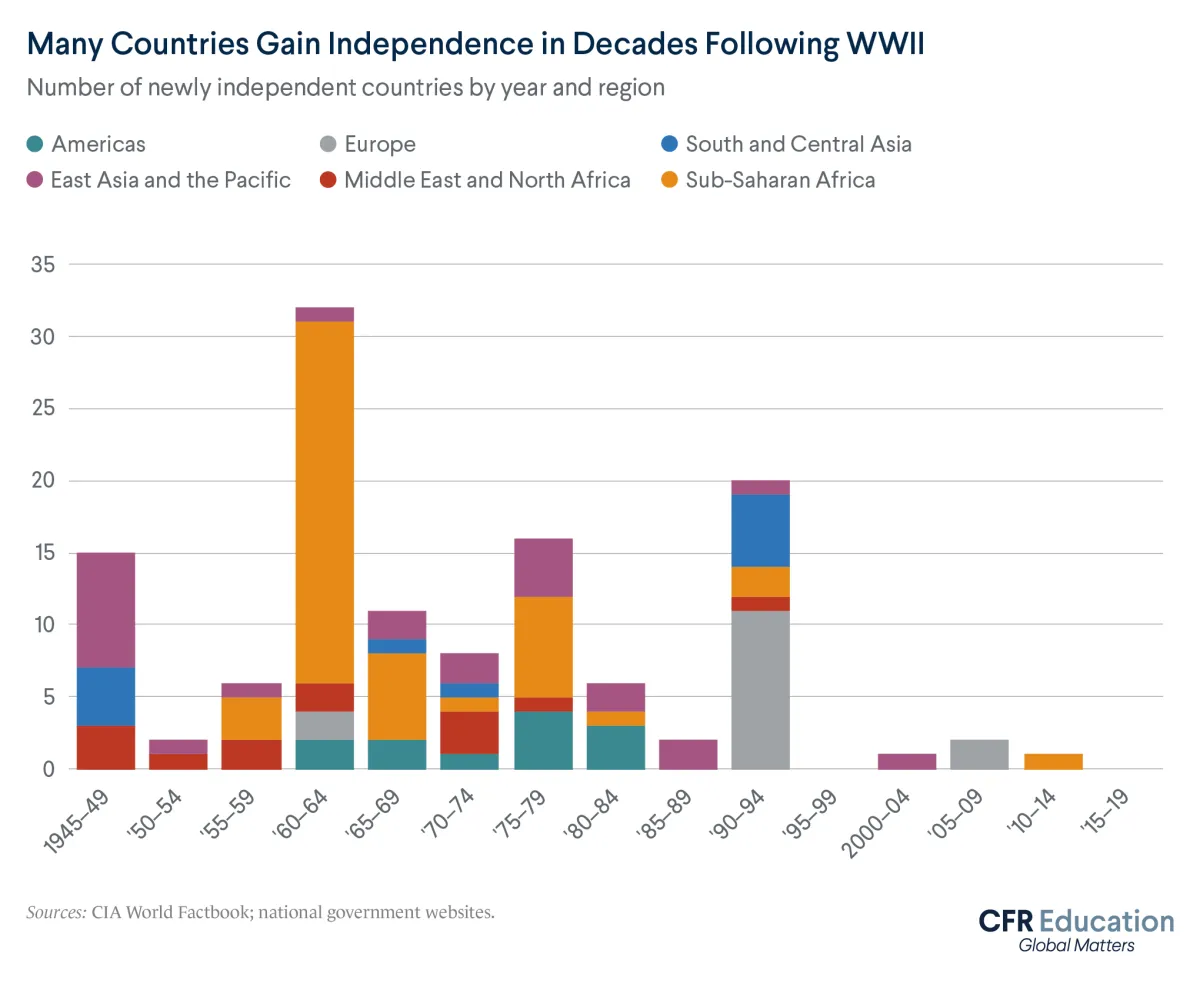

Fifty independent countries existed in 1920. Today, there are nearly two hundred. One of the motivating forces behind this wave of country-creation was self-determination. This is the concept that nations (groups of people united by ethnicity, language, geography, history, or other common characteristics) should be able to determine their political future.

In the early twentieth century, a handful of European empires ruled the majority of the world. However, colonized nations across Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, and elsewhere argued that they deserved the right to self-govern. Their calls for self-determination became rallying cries for independence.

Ultimately, the breakup of these empires throughout the twentieth century—a process known as decolonization—resulted in an explosion of new countries. The world map as we recognize it today is largely a result of decolonization.

But now that the age of empires is over, is that map set in stone? Not quite. Self-determination continues to play a role in deciding borders. However, the landscape is more complicated.

Many people around the world argue that their governments—many of which emerged during decolonization—do not represent the entire country’s population. The borders of colonies seldom had anything to do with any national (or economic or internal political) criteria. So when decolonization occurred, many of the newly created countries were artificial. As a result, these countries are rife with internal division.

However, for a group inside a country to achieve self-determination today, that country’s sovereignty—the principle that guarantees countries get to control what happens within their borders and prohibits them from meddling in another country’s domestic affairs—will be violated. In other words, creating a country through self-determination inherently means taking territory and people away from a preexisting country.

Whereas many world leaders openly called for the breakup of empires, few are willing to endorse the breakup of modern countries. Indeed, the United Nations’ founding charter explicitly discourages it. The fact that so many modern countries face internal divisions means few governments are eager to embrace the creation of new countries abroad. Countries fear that supporting self-determination abroad could set a precedent that leads to the unraveling of their borders.

A road to self-determination remains, but it is far trickier in a world in which empires no longer control colonies oceans away.

The world looked vastly different a hundred years ago. In 1914, European empires controlled nearly 60 percent of the world. The British Empire—the largest in history—spanned every continent. The French Empire ruled over territory greater than the size of Europe.

One factor driving such expansive imperialism was the quest for resources. The extraction of commodities from overseas colonies brought incredible wealth to European homelands. The Indian subcontinent, for example, accounted for nearly 40 percent of the British Empire’s gross domestic product in 1913. India’s production included items such as cotton, spices, and tea.

Colonized people often suffered greatly under the rule of empires. Colonized labor and land enriched faraway rulers at the expense of local communities. In one of the most extreme cases, in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo, up to ten million people died producing ivory and rubber for the Belgian Empire from 1885 to 1908. In India, millions died from famines from 1870 to 1930, as the British forced the colony to convert its farmable land from producing food crops to producing cash crops like cotton.

Amid such conditions, millions of colonized people demanded independence from the ruling empires. Their demands for self-determination grew stronger in the early twentieth century. Such calls for freedom intensified as European empires refused to cede their profitable colonies.

These vast, continent-spanning empires eventually began to break apart following World War II. Bankrupted by the war, many European countries could no longer afford to operate vast empires abroad. The cost of maintaining thousands of soldiers and administrators in colonies halfway around the world became increasingly unfeasible. This held particularly true for the United Kingdom, which emerged from the conflict with crippling debt.

Additionally, resistance to European rule grew stronger after World War II, when in places such as Algeria and India colonized people fought on behalf of the Allied Powers (including France and the United Kingdom) yet still were not granted greater self-rule. Many colonial nationalists cited the same principles of democratic liberty that were dominant in European capitals. They turned the colonizers’ language and ideals against them.

Furthermore, calls for independence were amplified with the postwar creation of the United Nations. Central to the United Nations' mission—and enshrined in the institution’s founding charter—was a “respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples.” Beginning in 1946, the United Nations made a list of seventy-four territories that were not self-governing. The UN asserted that these territories deserved self-determination. In 1960, the organization passed a resolution officially calling for an end to all colonialism.

Decolonization was hardly a straightforward process. Some countries such as Ghana and India achieved their independence through mostly peaceful negotiations. However, others such as Algeria and Vietnam fought long and bloody wars against fading empires that refused to relinquish their colonies. But in the three decades following World War II, many independence movements prevailed. By 1975, nearly eighty new members had joined the United Nations. Meanwhile, the European empires were mostly reduced to their homelands and a handful of small overseas islands and territories.

Though the age of empires is over, millions around the world still call for self-determination. They argue that governments continue to deny certain groups of people basic rights and the opportunity to determine their political futures. Rather than mostly European empires, today’s subjects of scrutiny are now often the governments of countries that emerged through decolonization. India, for example, gained independence in the 1940s, but many Kashmiris living there feel they still live under occupation. The Kashmiris cite political underrepresentation, economic exploitation, and cultural oppression. The same holds for Papuans in Indonesia. In Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, where Kurdish minorities straddle all four borders, many Kurds argue that the countries’ borders were artificially shaped with little regard for local identities, least of all their own.

Decades ago, the United Nations readily endorsed self-determination. The UN proudly oversaw the creation of dozens of new countries when the empires that ruled overseas colonies waned. But today the pace of country-creation has dramatically slowed. Though nations—such as the Kashmiris and the Papuans—have claims to self-determination, they face an uphill battle in achieving recognition. Self-determination cannot just be asserted; rather, it requires support from the countries that would be most directly affected. Such support is rarely forthcoming.

One reason for that reluctance is that self-determination competes with sovereignty, another central UN tenet. Sovereignty gives a government domestic authority, but self-determination undermines that authority. Self-determination can only occur by potentially taking territory and people away from a country. The United Nations is hesitant to endorse the breakup of modern countries. Moreover, governments are hardly eager to support the creation of new countries in the face of their internal divisions.

Only three new countries—East Timor, Montenegro, and South Sudan—have joined the United Nations this century. So why have most modern self-determination movements failed to achieve their goals? Who is entitled to self-determination, and where is the line drawn?

To better understand these questions and the tension between self-determination and sovereignty, let’s examine a handful of the world’s most active self-determination movements. What exactly do they want? What’s stopping them from getting it? What methods do they use to achieve their goals? And finally, how have other countries responded to calls for self-determination around the world?

The Demands

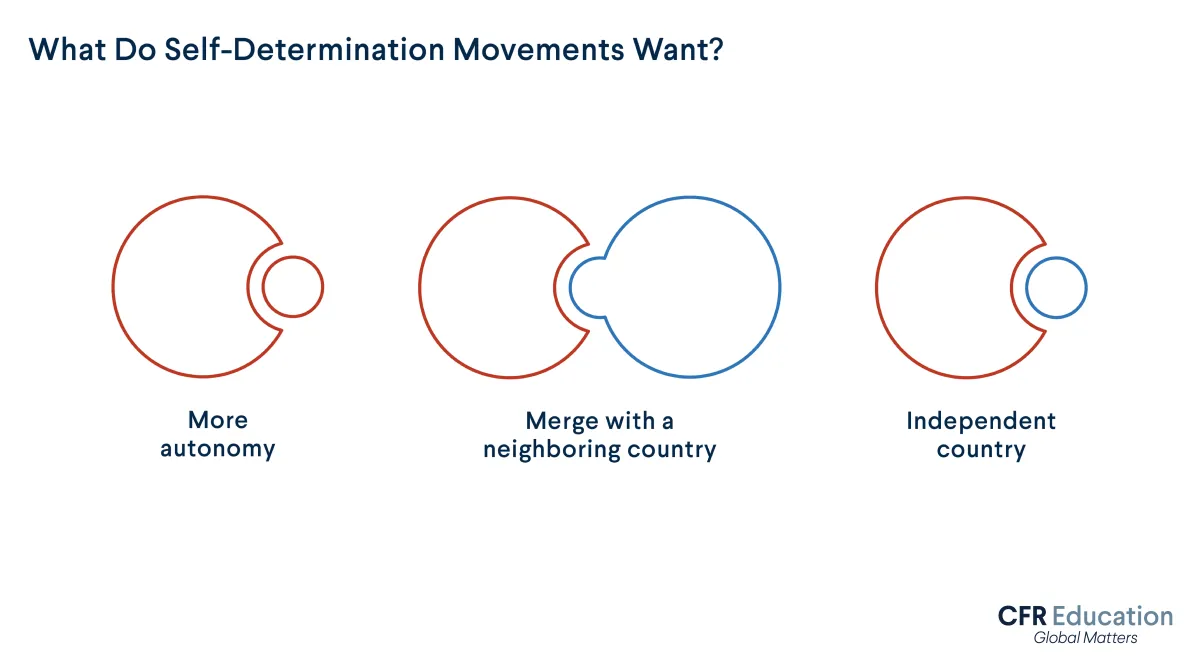

What exactly do self-determination movements want? Typically, they articulate demands for independence, merging with another country, or greater autonomy within an existing country.

First, let’s take a look at the most prominent type of self-determination movement: one seeking to create an independent country. These movements are driven by a belief that the existing government fundamentally cannot or will not represent the needs of a specific group within the country. Completely leaving a country is also known as secession.

Cameroon is divided by language: 80 percent of the country speaks French while the rest speaks English. This divide is the result of a 1961 referendum that merged a British and a French colony. Although the areas were meant to have equal status, French speakers have controlled Cameroon’s government for decades. The French-speaking majority advanced policies that have alienated the country’s English-speaking minority. In 2017, many English speakers believed they would never be granted equality under the Francophone-dominated Cameroonian government. As a result, leaders from Cameroon’s English-speaking regions unilaterally declared an independent country called Ambazonia. Cameroon, however, refuses to recognize this demand for independence.

Other movements seek to secede from one country and join another. Perhaps the group believes a current government does not meet its needs. Maybe it feels another country with historical ties would better represent it or that it simply needs to be united with its compatriots in another country.

In 2014, a new government in Ukraine sought to politically align the country more closely with the European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Soon after, Russian troops invaded Crimea, a region in Ukraine where nearly 80 percent of the population speaks Russian as a mother tongue. Crimea was formerly a part of the Soviet Union until Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev gave it away in 1954. The invasion in 2014 gave way to a highly contentious referendum held under Russian military pressure. In this referendum, the Crimean population voted to leave Ukraine and join Russia. Two days after the invasion, Russia officially annexed Crimea. The Kremlin justified this land grab by citing Crimeans’ right to self-determination. The Ukrainian government, United States, and European Union have refused to recognize the referendum’s legitimacy. They do not even recognize Russia’s control over the territory. This movement served as a precursor to a major conflict now embroiling Ukraine today. A full invasion of Ukraine by Russia in 2022 set alight one of the bloodiest conflicts in Europe since World War II. This conflict is still unfolding, and some experts suggest it reflects the re-emergence of global great power competition.

Approximately thirty million Kurds live in Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, forming one of the world’s largest ethnic groups without a country. For decades, the Syrian government banned the Kurdish language in schools and denied thousands of Kurds citizenship. But in 2013, during the chaos of the Syrian civil war, Syrian Kurds declared an autonomous region called Rojava. In this region, Kurdish authorities now run schools, administer the government, and defend local borders. Rojava’s leading political party emphasizes decentralization (in which people vote at the village level and local communities make as many decisions as possible). They ultimately envision a united Syria in which each region still has room to preserve its culture. However, the Syrian government has refused to recognize Rojava’s autonomy.

The Objections

Leaders of self-determination movements are generally clear about their demands. So what’s stopping countries from giving them what they want?

A country usually has multiple, often overlapping reasons why it wouldn’t want part of its territory to become independent, join a neighboring country, or even gain greater autonomy.

For one, countries seek to maintain control over territories that are rich in natural resources and have geostrategic value.

In the 1990s, a separatist movement led by Uighurs (a majority-Muslim ethnic group) started demanding the formation of an independent country called East Turkestan in China’s Xinjiang region. The movement accused the government in Beijing of forcing Uighurs to assimilate and give up their native language and religious practices. But to China, losing Xinjiang is not an option: the region holds an estimated one-fifth of China’s total oil reserves and 40 percent of its coal. These energy sources are critical to support China’s 1.4 billion people and sustain its economic growth. Xinjiang’s strategic location at the crossroads of Asia has become even more important as China builds railways and oil pipelines throughout the region. Moreover, Chinese political authorities do not want to set a precedent for the breakaway of other regions. China’s response to separatism has become increasingly severe.There are reports of the government interning more than a million Muslims in Xinjiang reeducation camps.

Additionally, some territories hold significant symbolic value, either domestically or internationally.

In India-controlled Kashmir, decades of political repression and heavy-handed military presence have led separatist movements to call for independence. But negotiations over Kashmir’s future are a nonstarter for the Indian government. Kashmir exists at the heart of India’s rivalry with Pakistan—the neighbors have fought two wars over the disputed territory. For India, control over Kashmir is not only about the region’s crucial water resources; it’s also a part of Indian nationalism amid a seventy-year feud with Pakistan.

The stakes are even higher for diverse countries with multiple self-determination movements. These countries’ governments worry a successful separatist movement in one part of the country could inspire separatists in another. They see caving to the demands of one group as creating a precedent for the unraveling of the country as a whole.

In Catalonia, a wealthy Spanish region, separatists feel that the government takes more in taxes than it returns in services. In 2017, separatists staged a controversial referendum seeking independence from Spanish control. Spain immediately responded by dissolving the Catalan parliament, arresting local leaders, and sending in police to crush protests. Why did Spain respond so forcefully? First and foremost, Spain wanted to keep its wealthiest region (home to Barcelona) under its control. However, Spain is also a unique country in that it comprises seventeen autonomous communities like Catalonia. Several of these autonomous regions have agitated for independence historically. For the Spanish government, secession in Catalonia could empower separatist movements elsewhere in the country (such as the Basque region). This could risk undoing the delicate balance between the central and regional governments.

The Methods

Once movements have established what they want and governments have made their reservations clear, what can movements do to achieve their goals?

The most peaceful process is to work with the central government to hold a referendum. The self-determination movement could have to agree to terms and conditions for the referendum, which takes time and compromise from both sides. However, this path is most likely to lead to both sides respecting the outcome of the vote.

In 2014, Scotland—one part of the United Kingdom—held an independence referendum. The British government firmly voiced its opposition to Scottish independence. However, it allowed the Scottish government full control over drafting the question and conducting the referendum. The British government allowed an independence vote to take place because it expected the referendum to fail. It calculated that a legitimate, transparent referendum that did not pass would decisively end this bid for Scottish statehood. In this instance, the government bet correctly: the referendum narrowly failed. Because the British government fully collaborated with Scotland’s government to ensure the referendum’s legitimacy, all sides respected the outcome. Still, in the wake of Brexit, some predict that the issue has not been definitively resolved. It remains a distinct possibility that Scotland could seek to hold another referendum in the future.

But Scotland’s experience is not the norm. More often, self-determination movements are not able to strike deals with the central government. Most referendums occur unilaterally, without the backing of the central government.. Holding a referendum without the government’s blessing is risky: although a successful referendum could gain the movement some concessions, the government will most likely deem the referendum illegitimate, and could even retaliate.

After decades of political oppression, Iraqi Kurds called for an independence referendum in 2017 in the country’s northern Kurdish autonomous region. Iraq’s government objected, claiming that any effort by the oil-rich region to secede would be illegitimate. The Kurdish regional government nevertheless proceeded with a unilateral referendum. The vote showed that Iraqi Kurds overwhelmingly favored independence. The Kurdish government calculated that even if Iraq didn’t recognize the referendum and grant independence, a strong showing would provide Kurds more bargaining power with the Iraqi government. But this plan backfired: Iraqi Kurds received no regional support, and the Iraqi government instead retaliated. It mobilized Iraqi troops to capture Kurdish cities, canceled international flights to Kurdistan’s airports, and imposed harsh sanctions on the region.

Having a referendum at all takes time and organization. Many groups, especially those that face extreme hostility from their central governments, are unable to provide enough stability. Extensive coordination is necessary to allow hundreds of thousands—or even millions—of people to vote. That’s why many movements, seeing no other alternatives, turn to violence to achieve their goals.

For the last fifty years, a movement favoring independence for resource-rich West Papua has called for a redo of a 1969 referendum that merged the region with Indonesia. Papuans insist the referendum was illegitimate—the few allowed to vote were forced at gunpoint to support joining Indonesia. However, the Indonesian government has rejected all demands to hold a second referendum. With little room for negotiation, a movement seeking secession from Indonesia has been locked in violent conflict. Papuan militants have engaged with the government’s security forces for decades, leading to hundreds of thousands of deaths. The Papuans continue to reject Indonesian control over their land and resources as well as non-Papuan migration from other Indonesian islands. Today, Papuan groups continue to fight an armed struggle against Indonesian authorities.

In the most intractable conflicts, self-determination movements often turn to the United Nations or international mediation. The hope is that outsiders can facilitate independence seekers' desire for a country of their own.

In 1947, the UN General Assembly voted to partition the British Mandate over Palestine into two states, one Jewish and one Arab. The Palestinians and Arab states rejected this plan. When Israel declared independence in 1948, neighboring Arab states invaded the country. When the fighting stopped, the state of Israel was firmly established. Meanwhile, Egypt controlled Gaza, and Jordan controlled the eastern part of Jerusalem and the West Bank. Another war in 1967 left Israel in control of Gaza, the West Bank, and all of Jerusalem. To this day, the Palestinians do not have a country of their own; they exercise limited control in 40 percent of the West Bank and greater control in the Gaza Strip.

The current situation resulted from a process that began in 1993 when Israelis and Palestinians met in Oslo to formulate a process of increasing Palestinian autonomy. The ultimate goal of the Oslo Accords was to facilitate the establishment of an independent Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza. A resulting two-state solution would leave Israel and the Palestinian state living alongside one another in peace. Diplomacy could not, however, resolve some of the conflict’s toughest challenges. Despite progress in Oslo, significant hurdles remained—such as defining the borders of a future Palestinian state, determining the fate of Israeli settlements built in the West Bank, reconciling Israeli security with Palestinian sovereignty, addressing the return of Palestinian refugees, or deciding who would control the holy city of Jerusalem. Subsequent negotiations led by the United States came close but never succeeded in brokering a mutually acceptable agreement. In 2005, Israel withdrew unilaterally from Gaza. However, Israel has continued to occupy the West Bank and expand its presence there and in Jerusalem. The establishment of a Palestinian state remains a distant prospect. Instead of complete self-determination, some Palestinians now advocate for their equal rights under Israeli sovereignty.

The Recognition Calculus

For self-determination movements that seek independence, recognition from other countries is essential. Recognition leads to legitimacy and entry into international organizations such as the United Nations. But why are some movements recognized as legitimate while others are largely ignored?

Even though many self-determination movements make strong cases (that self-determination is a UN-supported right and that often governments have committed severe human rights abuses against the group seeking a country of their own), most efforts in recent decades haven’t received widespread support.

In fact, among the movements described above, the vast majority have received little to no support from foreign countries.

In some cases, governments choose not to recognize foreign self-determination movements for fear that endorsing the breakup of a country would poison their relationship with that government. Even the United States, which has militarily supported Iraqi Kurds for years, refused to back its independence referendum due to opposition from the Iraqi government, a U.S. partner. The East Turkestan independence movement in Xinjiang has been unable to garner endorsements even from Central Asian countries with populations that are ethnically similar to Uighurs due to those countries’ deep reliance on China for trade and investment. Many countries have also remained silent on the Papuan conflict in part given the Indonesian government’s close ties with multinational companies that extract West Papua’s oil, minerals, and timber. Supporting a separatist movement within another country practically guarantees damaging a relationship with that country’s government.

In other cases, a country that has a secession movement is unlikely to support such movements elsewhere given the precedent it could set at home. This mindset contributed to China joining the Spanish government in opposing Catalonia’s 2017 independence referendum. Similarly, Russia, home to plenty of separatist movements, has insisted Kashmir is an internal Indian issue that doesn’t concern other countries.

But not every self-determination movement has failed to garner support.

So far this century, three countries have gained independence and entry into the United Nations. East Timor became independent from Indonesia in 2002; Montenegro declared independence from Serbia in 2006; South Sudan, the world’s newest country, came into being after South Sudanese people overwhelmingly voted in 2011 to secede in a peaceful referendum sanctioned by the Sudanese government.

Recognition as an independent country is not only about proving the right to self-determination. It depends on the willingness of other countries to let someone new into the club. These considerations are calculated and political: does the introduction of a new country threaten existing ones’ sovereignty and interests or not?

It’s an uphill battle, but self-determination movements today still have hope of achieving their goals. Even in the twenty-first century, the world map is not set in stone just yet.