What Happened When China Joined the WTO?

The United States thought it was directing the show when China acceded to the World Trade Organization. Instead, China wrote its own script.

Today the House of Representatives has taken an historic step toward continued prosperity in America, reform in China, and peace in the world. . . it will open new doors of trade for America and new hope for change in China.

In the spring of 2000, China was trying to become a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The U.S. House of Representatives had just approved normalizing trade relations with China. The vote was effectively a U.S. endorsement of China’s accession, and President Bill Clinton, a major proponent of China’s bid, voiced his economic and strategic hopes for the U.S.-China relationship.

The WTO is the global trade rule-setting institution. It has 166 members as of 2024, and all decisions are made unanimously. It promotes freer trade by requiring all members to adhere to certain principles, emphasizing low and predictable trade barriers. In exchange, members are guaranteed better deals with other WTO member countries.

China wanted to join the WTO because it would allow China access to new trading partners and better rates with current ones, raising prospects for improved living standards domestically and giving China a seat at the table in a globalizing world.

The United States wanted something, too: for China to get on board with a U.S.-led, liberal-democratic order and move away from its communist model. But that's not quite what happened.

U.S. hopes . . .

With the world’s sixth largest economy and a population of one billion people, China in 2000 was already a massive market and clearly a rising power. Before 1978, China had a socialist-planned economy and was largely isolated; since then, it had been gradually opening up its economy to the rest of the world. WTO membership would accelerate that process.

Clinton and others championed China’s accession for a few reasons:

- China would have to change its policies to adhere to WTO rules, reducing tariffs and guaranteeing intellectual property rights, among other things, while countries such as the United States would have to give up little in return.

- The United States argued that membership in an international organization such as the WTO would act as a check on China’s communist government, speeding up its transition to a market economy and encouraging it to have a greater stake in setting global rules. This was not a new idea; Clinton’s predecessor had operated under the same assumption that free trade leads to democracy: “No nation on Earth has discovered a way to import the world’s goods and services while stopping foreign ideas at the border,” said George H.W. Bush.

- It would also legitimize the WTO itself: China was the biggest trading country outside the organization, and the WTO could not really claim to be a global organization without it.

. . . versus reality

In 1999, amid talks of WTO accession, a former U.S. government official predicted that China would “join the club of nations well along the road to democracy,” and that its per capita gross domestic product (GDP) would reach seven thousand dollars by 2015—in other words, China would hit political and economic milestones that the United States believed would naturally occur in tandem. Instead, China achieved that financial benchmark two years early, in 2013. But it is still far from being a democracy.

We can break the results of China’s WTO accession down into a few categories:

Economically, the United States saw some benefits and some downsides.

- Consumers broadly benefited from China’s WTO entry because they could buy goods from China at lower prices.

- Corporations profited from increased access to China’s massive market. In 2017, for example, Chinese consumers accounted for about 15 percent of Apple’s sales, and since 2001, U.S. exports to China have skyrocketed by 450 percent.

- However, labor unions in manufacturing and factory work opposed a WTO accession deal, certain that cheaper labor in China would cost jobs in the United States. And they were right: between 1999 and 2011, almost 6 million U.S. manufacturing jobs were lost. A landmark study attributed nearly 1 million of those manufacturing job losses, and 2.4 million total job losses, to competition from China. But because major technological advances such as automation occurred in that same time frame, economists disagree about exactly how responsible Chinese competition was for job losses in manufacturing.

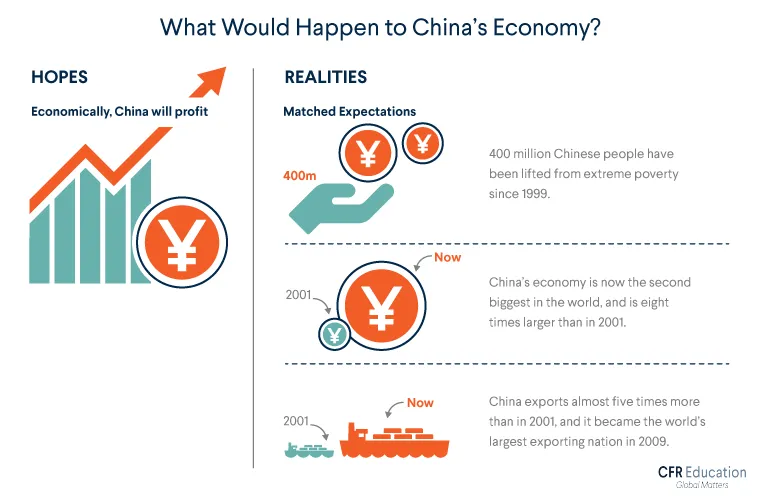

Meanwhile, for China, the economic impact has been remarkably positive:

- From 1990 to 2015, the share of the Chinese population living in extreme poverty (defined as living on less than $1.90 a day) declined from 67 percent to under 1 percent.

- China’s economy is eleven times larger than it was in 2001.

- Trade in goods between the United States and China increased from less than $100 billion in 1999 to $558 billion in 2019. China surpassed Germany to become the world’s largest exporter in 2009.

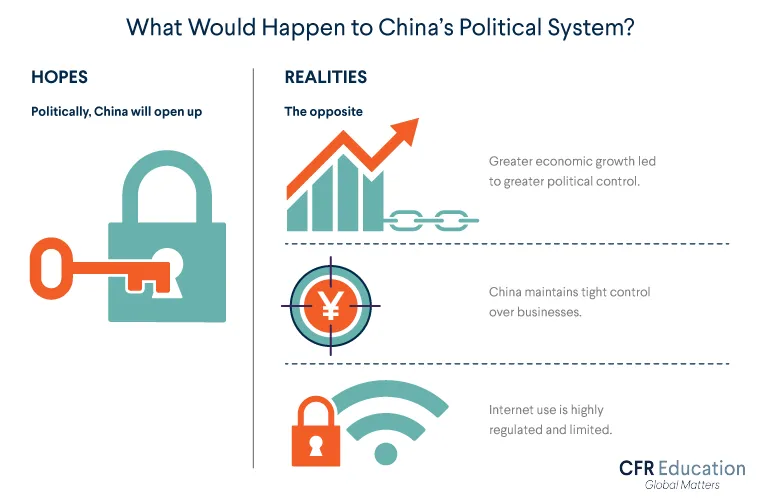

Politically, the result is less ambiguous: China did not conform to democracy in the way the United States had hoped. In fact, its vast economic gains have only legitimized the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which President Xi Jinping believes is central to maintaining economic stability and enabling China to dominate technology-driven industries.

China’s tight government controls extend to the internet, which was supposed to be a gateway to reform and innovation. China regulates internet use, limiting access to commerce and social media. China has blocked political organizing by threatening—and sometimes jailing—those who post critical comments online. The Chinese government also uses the internet to identify and track dissidents.

Why did Clinton and others believe the WTO would rein China in?

The WTO is an offshoot of a post-World War II trade agreement that countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom created to encourage economic ties and maintain a peaceful world—a world of international institutions that all promoted similar values.

The WTO rules were not written with China, or its unique economic-political structure, in mind. China has elements of a capitalist system, but is still run by a communist government. There are many influential government-owned companies (China’s oil and gas giant, Sinopec, took in more money in 2019 than any other company in the world, other than Walmart), and even private companies are heavily subjected to government influence. According to the China Daily (itself owned by the CCP), nearly 70 percent of the almost two million private companies in China had internal CCP groups in 2017.

Instead of conforming, China is using the WTO to its advantage

The twist is that China has benefited greatly from the WTO, taking advantage of the provisions that suit its interests while skirting less convenient restrictions. China has incurred criticism for carrying out certain market-distorting practices, and has been accused of cheating the system in various ways. Sometimes it violates the letter of the law, sometimes the spirit.

The allegations against China have manifested in official WTO disputes. Since 2001, the United States has lodged twenty-three (out of a total of forty-three) cases against China, sometimes as a codefendant with Canada, the European Union, and others.

The bulk of allegations against China say that China promotes its exports while remaining largely closed to foreign goods, making it more difficult for companies from other countries to do business in China.

One of the most discussed problems with Chinese trade practices is forced technology transfer. U.S. officials allege Chinese companies steal technological knowledge from the foreign companies operating in China.

However, this rarely comes up in WTO cases because it is not always clear that they are actually violating any WTO rules.

How does it work? One way is through joint-venture partnerships: China often requires foreign companies entering the Chinese market to partner with Chinese firms, which is allowed under WTO rules. The terms of these treaties, which are negotiated outside the scope of the WTO, sometimes require foreign firms to share technology secrets with Chinese companies. But because many Chinese firms are owned or influenced by the government, the companies are effectively sharing their technological secrets with the Chinese government.

Particularly when it comes to forced technology transfers and state subsidies (providing direct support to Chinese industries through state funding and tax breaks), China is often breaking no explicit rules. But they are seen as violating the spirit of WTO regulations.

Sometimes the Chinese government will take advantage of the lack of WTO regulations governing certain issues. For example, it was found to have undervalued its currency by 30 percent for years after joining the WTO, which made Chinese exports cheaper—but there is no WTO provision on currency manipulation, which makes tackling this issue more difficult for China’s trading partners.

Is China changing its ways? Short answer: No

When found guilty of WTO rule violations, China has taken steps to rectify its behavior (more than can be said for the United States and the European Union, which have both ignored rulings). But, as it is responding to complaints, China has simultaneously announced plans to ramp up some policies that the United States finds fault with, such as state subsidies.

Why would China want to change the ways it works within the WTO? The country has reaped enormous benefits since joining: it now has an economy almost one hundred times larger than it was in 1978, and its middle class is growing. It has increased its international involvement without conforming to the playbook of a Western, democratic world order, and it is becoming a leader in its own right.

Even if China was less influential, the WTO would unlikely be able to rein it in. The WTO’s relevance is waning, stemming from the fact that its rules have not been updated in more than twenty-five years. China has learned, quickly and effectively, how to navigate the rules so the global economy works for it, not against it.