How to Protect Against Extreme Weather

Climate change is making extreme weather more frequent and intense. What can governments do to protect their populations?

Climate change is driving up the danger from extreme weather events. Hurricanes and other storms, wildfires, and droughts are increasing in severity, with devastating consequences for communities across the globe. Heavy rainfall and flooding displaced over half a million people in southern Brazil in May 2024, and Australian bushfires in 2019 and 2020 burned more than seventy-two thousand square miles of land. In the United States, the five years from 2020 to 2024 were the most destructive on record, with 115 separate weather events that caused more than $1 billion in damage.

As global warming increases, the toll of extreme weather events will worsen. But certain adaptations can reduce their risk. These include better forecasting technologies, improved disaster-response systems, and infrastructure improvements.

This learning resource explores climate change’s severe weather repercussions and what governments and communities can do to adapt.

How climate change worsens extreme weather

For decades, climate scientists have predicted that rising greenhouse gas emissions would intensify many types of extreme weather. In recent years, researchers working in a field known as attribution science have increasingly been able to observe that happening.

Attribution scientists use statistical analysis to link weather events directly to rising greenhouse gas emissions. One of the main strategies involves looking at historical climate data to determine how likely a specific event, such as a hurricane, is to occur the way it did. The scientists then simulate a world in which humans have not emitted greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, in order to determine the likelihood that the same event would occur in a world without climate change. Comparing outcomes in the real world to a simulated model allows them to determine whether humans made a certain event more likely to happen, more severe, or both.

Let’s take a closer look at how climate change affects certain weather events:

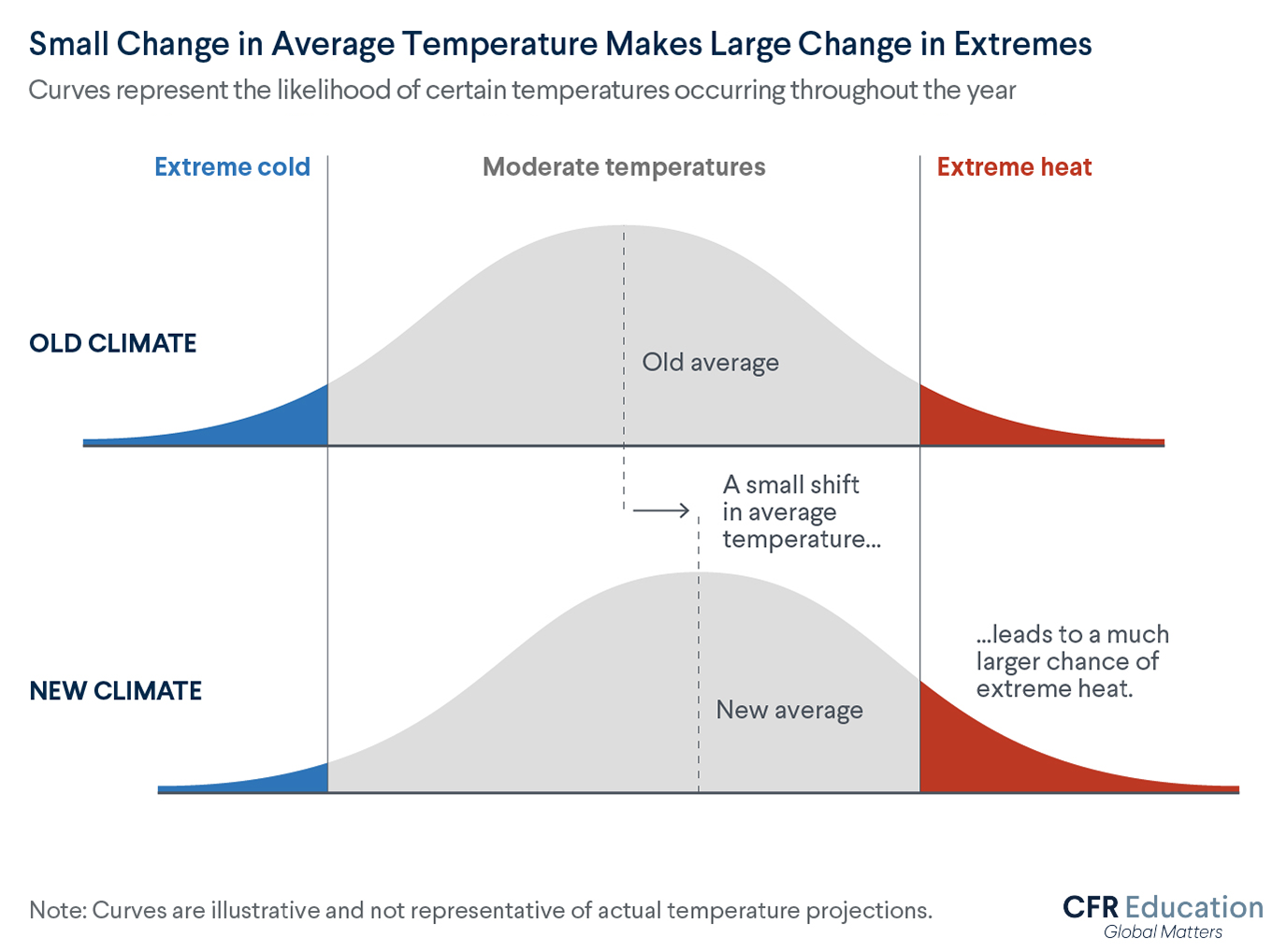

Heat waves: Even a small increase in global average temperatures can cause heat waves— periods of extreme heat—to become more likely and reach new extremes. In 2019, for example, researchers found that a deadly heat wave in France had been made 1.5°C to 3°C hotter and up to ten times more likely because of climate change.

Precipitation: Higher temperatures from climate change can cause more water to evaporate, while also allowing the air to retain more moisture. In many areas around the world, that results in heavier rain or snowfall. Extreme precipitation events can cause devastating flooding. In 2022, for instance, Pakistan experienced extreme rainfall from monsoons. The resulting floods killed 1,500 people, displacing 30 million more, and causing billions of dollars’ worth of damage to crops. One study found that climate change had made rainfall in Pakistan up to 75 percent more intense.

Hurricanes and extreme storms: The increased evaporation and moisture retention that accompanies warmer temperatures also enables storm systems, including hurricanes, to pull in more moisture and intensify. Rising sea levels caused by melting arctic ice also make storm surges higher, leading to more coastal flooding during storms. Those factors contribute to increasingly deadly hurricanes. Hurricane Harvey, for example, pummeled Houston with up to forty inches of rain in August 2017. Attribution studies have determined that climate change made such heavy rainfall three times more likely to occur.

Droughts: While climate change causes more frequent and intense rainfall in some areas, it contributes to worse droughts in others. Increased evaporation and moisture retention in the air can allow more moisture to transfer from the soil to the air. Changing weather patterns can also mean that some areas receive less precipitation than they used to. All of that contributes to drier conditions, covering larger areas, for longer periods. Droughts can have catastrophic consequences. In East Africa, for example, a total of six rainy seasons have failed since October 2020, causing the worst drought in more than forty years. Millions of people were pushed into hunger by ruined crops and dead livestock. When rainfall finally arrived in 2023, it compounded the crisis. The dry soil couldn’t adequately absorb the heavy rains, leading to deadly flash floods. Climate researchers concluded that climate change makes such droughts at least twice as likely.

Wildfires: Warmer temperatures and drought conditions, both strengthened by climate change, are also fueling an increase in the extent, severity, and sometimes frequency of wildfires worldwide. In the United States, for example, the ten largest wildfires by acreage have all occurred within the last twenty years. Those years have also been the warmest on record. The risk is not limited to the United States, however: Australia’s deadly wildfire season from 2019 to 2020 burned nearly one hundred thousand square miles. The fires also killed or displaced nearly three billion animals, pushing some species to the brink of extinction. Climate change raised the risk of those fires by at least 30 percent.

The global increase in extreme weather, climate, and water events has caused hundreds of thousands of deaths and hindered socioeconomic development. According to the research group World Weather Attribution, more than half a million people [PDF] have been killed by climate change–worsened disasters since 2004. Beyond threatening lives, such weather is also costly. Between 2014 and 2023, climate-related severe weather events caused an estimated $2 trillion in damage around the world. As climate change heightens the threat of extreme weather, those harms are expected to increase. By 2050, climate change could cause an additional 14.5 million deaths. Accordingly, governments around the world have sought ways to increase resiliency and preparedness in the face of worsening climate disasters.

How to safeguard against extreme weather

Forecasting: Accurately predicting extreme weather events has the potential to save lives. With enough advance warning, communities can better prepare to handle an extreme weather event or evacuate areas to get people out of harm’s way.

The power of weather forecasting has multiplied over the past several decades. Traditional weather forecast models are now faster and more accurate than ever before. In the 1970s, for example, a forty-eight-hour forecast for predicting a hurricane’s path over the Atlantic Ocean had a margin of error between two hundred and four hundred nautical miles. Now, that error has been reduced to just fifty miles. These improvements have created tangible benefits. Improvements made within U.S. forecasting infrastructure since 2007 are estimated to have reduced the total cost by 19 percent—which equals billions of dollars per hurricane.

Advances in forecasting technology continue to help communities better prepare for climate change. Artificial intelligence (AI) programs, for example, are increasingly informing forecasting methods. AI models can incorporate vast amounts of data and identify patterns that traditional forecasting models could overlook. They can also generate forecasts faster and cheaper than some traditional methods.

However, despite advances in forecasting technology, many countries, especially low-income ones, still have underdeveloped forecasting abilities. In fact, a seven-day forecast in a rich country can be more accurate than a twenty-four-hour one in a poorer country. Lack of forecasting coverage is also a problem. About one-third of the world’s population lacks access to adequate early-warning systems. Many live in developing countries and island nations particularly prone to extreme weather’s effects. Some agencies from wealthier countries and the United Nations are helping other regions and countries develop their forecasting capacities. For example, the U.S. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration runs a yearly program in which meteorologists from African, South American, and other tropical countries can visit and learn with the U.S. weather service. Still, forecasting deficiencies continue to hinder disaster preparedness around the world.

Response: When extreme weather events occur, a community's ability to respond effectively can mean the difference between life and death. Disaster response involves search and rescue efforts, as well as the provision of food, water, and medical attention to those who need it. It also necessitates restoring critical infrastructure like roads, power, and water, and evacuating communities from unsafe areas.

Effective disaster response requires trained personnel and resources. It also demands efficient communication and coordination of local, state, and federal efforts. As climate change worsens, response systems can boost their readiness by developing and improving action plans for extreme weather events. They can train first responders and improve lines of communication across organizations and agencies that participate in response efforts.

New or improved technologies can also strengthen disaster response. For example, modular bridges can help quickly restore damaged roadways, and satellite internet services or wireless mesh networks can repair communication networks.

One crucial obstacle remains, however. Effective disaster response needs funding, which governments can be hesitant to provide. In the United States, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has had to temporarily pause ongoing relief efforts ten times since 2001 due to funding shortages. As climate change continues and disasters become more frequent, response systems risk being stretched to their limits.

Adaptation Infrastructure: Communities can reduce the demands of emergency response resources by improving their resiliency. That means investing in resilient infrastructure, such as seawalls to safeguard against flood damage, cooling centers to offer shelter against heat waves, and mandates that require new buildings be made to withstand stronger winds.

Additionally, nature-based solutions like restoring wetlands and mangroves can provide natural buffers against storm surges and flooding. They also help to protect local biodiversity. Investments in green roofs and urban tree planting can help cities mitigate urban heat and improve air quality. Many such nature-based solutions are also far more cost-effective, achieving an area’s adaptation goals at a fraction of the cost of building new infrastructure.

Such infrastructure upgrades can be prohibitively expensive, especially for many low-income countries. However, compared to the costs of disaster response, an ounce of prevention is often worth a pound of cure. The World Bank estimates that every dollar invested in resilient infrastructure saves low- and middle- income countries four dollars in avoided damages.

Relocation: As climate change worsens, some areas could simply become impossible to safely inhabit. In low-lying coastal areas or dry, fire-prone regions, some residents are already facing the difficult decision of whether to permanently relocate. As climate change worsens, policymakers will increasingly need to decide whether to adopt policies that encourage or even mandate relocation from some areas.

In cases where extreme weather events make certain areas uninhabitable, relocation becomes a necessary, albeit challenging, option.

Managed retreat, the process of moving communities out of harm’s way, is often considered a last resort due to its financial, social, and emotional costs. However, as climate change continues to intensify catastrophic weather events, that last resort could become unavoidable in some places. Governments can facilitate the process by offering buyouts for properties in high-risk zones, funding the development of new housing, and ensuring that relocated communities have access to employment opportunities, schools, and health care.

However, relocation is not without its challenges. Many people are reluctant to leave their homes due to cultural ties, economic constraints, or skepticism about the risks. Additionally, poorly planned relocations can lead to social and economic disruptions, particularly for already marginalized populations.

None of those adaptation strategies are easy, and all require significant investment. However, even if countries successfully reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and meet the goals laid out in the Paris Agreement, climate change–worsened weather will continue to take a toll around the world. With improved technology and infrastructure, coordinated response efforts, and—if need be—planned relocation, communities can better protect themselves from the worst effects of climate change.