What Is Fascism?

In this free resource, learn how Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler rose to power and the lessons their political journeys hold for today.

Over the past few years, people have thrown around the term "fascism" pretty loosely. It has been used to criticize any number of issues—proposed environmental regulations aimed at curbing greenhouse gas emissions, stay-at-home orders during a global pandemic, and even legislation limiting the size of sodas.

But usage of the term extends to issues far more serious than Big Gulps. Authoritarian leaders in various countries have been labeled fascists by critics in recent years. The term has even sparked intense debate in the United States. In the run-up to the 2024 presidential election, proponents of both major party candidates, and even the candidates themselves, have characterized their rivals as fascists.

The term fascism is used broadly today, but it has very specific origins rooted in a history of highly divisive and highly destructive European political movements. These movements arose in the era between World Wars I and II and fundamentally changed the political nature of the European continent.

So what exactly does fascism mean? Where does this political ideology come from? And to what extent do leaders today display fascist tendencies? This resource explores those three questions by diving into the history of the world’s most notorious fascist leaders: Benito Mussolini of Italy and Adolf Hitler of Germany.

What does fascism mean?

Many experts agree that fascism is a mass political movement that emphasizes extreme nationalism, militarism, and the supremacy of the nation over the individual. This model of government stands in contrast to liberal democracies that support individual rights, competitive elections, and political dissent.

In many ways, fascist regimes are revolutionary in nature. They advocate for the overthrow of existing systems of government and the persecution of political enemies. However, such regimes are also highly conservative in their championing of traditional values.

And although fascist leaders typically claim to support the everyman, in reality, their regimes often align with powerful business interests.

Let’s unpack a few of these hallmark characteristics of fascist leaders and their movements:

Fascist Leaders

Swipe through to learn more about 6 fascists and their movements.

Extreme nationalism: Fascist leaders believe in the supremacy of certain groups of people based on characteristics such as race, religion, ethnicity, and nationality. Hitler and his Nazi Party, for instance, advanced the idea of Aryan (essentially white Germanic Christian) racial superiority. The most extreme example of this ethnocentric nationalism manifested in the Holocaust. During the Third Reich, the Nazis executed a state-sponsored and systematic campaign of murder and persecution against those deemed inferior. At least eleven million people were killed, including six million European Jews and five million gay people, Roma people, and people with disabilities, among others.

Cult of personality: Fascist regimes cultivate images of their leaders as great figures to be loved and admired. This cult of personality is often perpetuated through mass media and propaganda. In Italy, Mussolini’s photograph hung in the walls of classrooms while his political party encouraged all good citizens to purchase a Mussolini-themed calendar each year. To maintain this powerful image, Mussolini prohibited journalists from reporting on his age or health issues. He often went as far as to take photographs posing with a lion or riding a horse to project his power. Mussolini, or Il Duce (Italian for “the leader”), took on a mythical status. The Pope chalked up Il Duce’s survival of assassination attempts to divine intervention, adding to Mussolini’s mystique.

Popular mobilization: Although both authoritarian and fascist governments are anti-democratic, leave little room for dissent, and strive to centralize power, the two types of regimes are not the same. Authoritarian governments want their populations to remain passive and demobilized. On the other hand, fascist regimes seek to energize public participation in society through government-organized channels. Both Mussolini and Hitler, for instance, drew massive crowds in rallies intended to stir up enthusiasm for the country, the party, and the leader.

How did fascists come to power?

Mussolini and Hitler rose to power swiftly, but their countries’ transformations from constitutional government to fascist regime did not take place overnight. Rather, the two countries experienced a similar pattern of liberal decay. First, fascist parties gained a foothold in government through initially democratic means. However, over time, the party consolidated power, and ultimately secured their dictatorship.

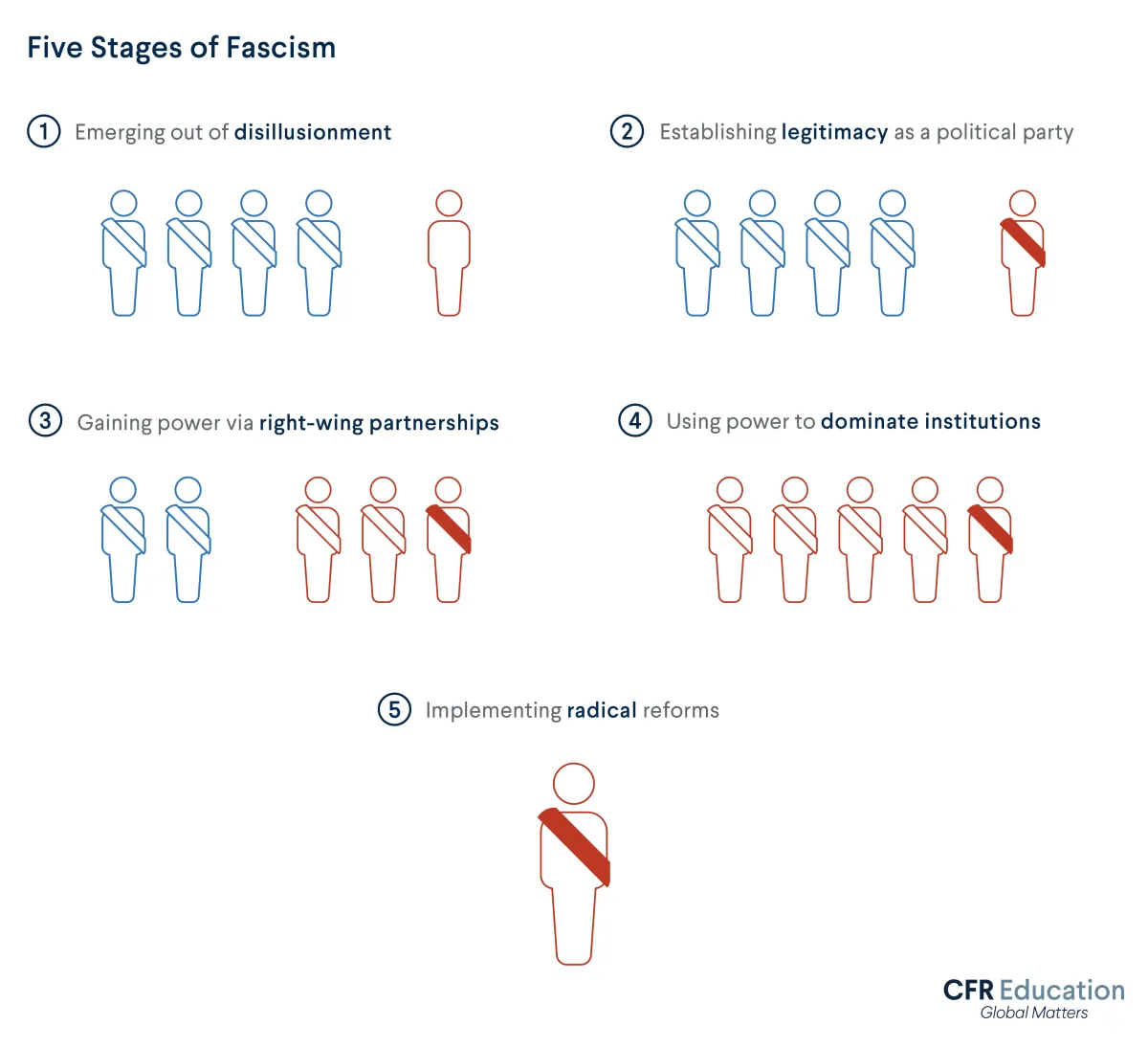

In this section, we’ll walk through the five stages of fascism—a framework coined by fascism scholar Robert Paxton. This framework illustrates the similar steps through which individuals like Mussolini and Hitler came to power.

Stage one: Emerging out of disillusionment

Mussolini and Hitler rose to prominence in the aftermath of World War I. The respective politicians capitalized on the political and economic fallout of the Great War by inflaming popular dissatisfaction with the countries' leaders.

Hitler pointed to the harsh and humiliating terms of the Treaty of Versailles as a means to drum up popular support. The treaty forced Germany to accept blame for World War I, give up 13 percent of its European territory and overseas colonies, limit the size of its army and navy, and pay reparations (financial damages) to the war’s winners. In the aftermath of the Great War, Germany was left in economic despair, international embarrassment, and political instability. Hitler would gain followers by promising to tear up the Treaty of Versailles and restore the country’s honor.

Meanwhile, the economic crisis that followed World War I further eroded public confidence in the existing political establishment. In the immediate aftermath of the war, Germany suffered hyperinflation—a situation in which prices skyrocketed so quickly that German currency lost much of its value. Moreover, Italy experienced a two-year period of mass strikes and factory occupations, with millions unemployed.

Stage two: Establishing legitimacy as a political party

Fascist leaders capitalized on popular disillusionment to source their political power. Mussolini and Hitler created their own political parties to challenge the ruling establishment through the ballot box and, often, violence in the streets.

In 1919, Mussolini created Italy’s Fascist Party, which was unabashedly pro-Italian nationalism and anti-socialism. The group attracted fervent followers who organized armed militias known as the squadrisiti (or “Blackshirts” per their uniforms). These fascist militants often skirmished with Italian socialists in the streets.

Germany’s Nazi Party (originally founded as the National Socialist German Workers’ Party) also emerged in the aftermath of the war, in 1920. With many Germans shocked by the country’s defeat in World War I, the Nazis pushed a narrative that argued Germany could have won the war if not for unrest at home. This myth falsely accused Jewish people and left-wing activists of undermining the country’s war effort. The Nazis also blamed Germany’s new democratic government for abandoning the conflict and accepting harsh peace terms from the Allied Powers. Propelled by this vision, the Nazis went from winning 3 percent of the vote in the 1928 parliamentary elections to 44 percent in 1933. They were also supported by their own paramilitary group known as the Sturmabteilung (or “Brownshirts”). This militant army—like the squadristi—clashed with the party’s rivals.

Stage three: Gaining power via right-wing partnerships

Interwar Europe primarily featured two political groups: conservatives and socialists. A third option—fascists—would gain power by partnering with conservatives, who advocated for traditional values, including nationalism and law and order. Conservatives recognized that fascists wanted to overthrow the political establishment; however, the two groups found common cause over their shared hatred and fear of socialists. Communist regimes were gaining influence across Europe after first coming to power in Russia in 1917 and were seen as an existential threat to conservative values.

In Italy, conservatives combined forces with Mussolini’s Fascist Party to form a governing majority in parliament following elections in 1921. Meanwhile, in Germany, the country’s conservative leaders allied with the Nazis. Both conservative parties believed a fascist coalition would be a short-term compromise to prevent socialists from taking power. After the Nazis won the largest share of votes in 1932, the country’s president appointed Hitler chancellor of Germany. Even still, conservatives expected to control government affairs while taking advantage of Hitler’s charisma. That expectation, of course, would turn out to be a miscalculation.

Stage four: Using power to dominate institutions

Upon rising to power, Fascist parties attempted to consolidate political authority.

Mussolini’s Fascist Party won elections in 1921 as part of a coalition. The following year, the Italian king appointed Mussolini prime minister after a mass fascist demonstration known as the March on Rome. As the Fascist Party gained more power, many feared civil war if Mussolini were denied power. The Fascists, however, did not seize absolute authority, as traditional institutions like the Catholic Church still retained a certain degree of independence.

The Nazis, on the other hand, took total control over government and society. Hitler removed all non-Nazis from government shortly after becoming chancellor in 1933. He would go on to pass laws stripping Jews of citizenship and expelling anti-Nazi professors from universities. To further consolidate Nazi control, Hitler banned rival political parties and enabled himself to rule by decree (meaning he could single-handedly—and without oversight—create future laws). Germany became a one-party country: the Nazis claimed to have won more than 90 percent of the vote in unfree and unfair elections in November 1933. After1938, Germany ceased holding elections altogether.

Stage five: Implementing radical reforms

With near-total or absolute control over society, fascist leaders exercised their power in increasingly radical ways.

Mussolini’s Italy carried out violent colonial campaigns across Africa. In Libya, colonial troops employed chemical weapons against local resistance movements and imprisoned their members in concentration camps. And in 1935, Italy invaded Abyssinia (now Ethiopia), where virulent racism led to mass instances of rape and the indiscriminate killing of hundreds of thousands of people. Mussolini’s regime did not carry out the same scale of ethnic violence at home. However, his government proclaimed white, Christian Italians to be descendants of the Aryan race and banned Black and Jewish people from marrying them.

Hitler’s Nazi Germany remains the only example of full radicalization of a fascist movement. As Germany’s absolute ruler, or führer, Hitler destroyed all political opposition; ordered the genocide of millions; invaded countries across Europe; and, in partnership with Mussolini, launched World War II—the deadliest conflict in human history. Even seventy-five years after Hitler’s death, his rise to power and Germany’s fall from democracy into fascism serve as frightening reminders. If racism and extremism are left to fester in politics, no liberal democracy is safe.

Does fascism exist today?

Most scholars understand fascism as a phenomenon that existed between World Wars I and II, with Mussolini and Hitler as its primary exponents. But that doesn’t mean that the characteristics of fascism can never reappear. Leaders and political groups can still try to replicate the fascist playbook to consolidate power.

Even if a group or movement does not progress through all five stages of fascism, it can still exhibit similar elements. This is increasingly apparent at a time of global democratic backsliding, in which democracies are under attack. However, democracy is not being besieged by foreign invaders but by domestic leaders who are weakening their countries’ institutions that protect political freedoms and civil liberties.

Against this backdrop, it's imperative to understand the stages of fascism. So long as democracy remains under attack, it is crucial that we can identify the conditions that once enabled the rise of such destructive regimes.