U.S. Foreign Policy: Sub-Saharan Africa

The United States’ relationship with sub-Saharan Africa dates back to the transatlantic slave trade era, even before the country’s independence.

The United States’ relationship with sub-Saharan Africa dates back to the transatlantic slave trade era, even before the country’s independence. But for centuries thereafter, diplomatic relations between the two remained limited until a wave of sub-Saharan African countries gained their independence following World War II. With the advent of the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union jockeyed to bring the newly independent countries within their respective spheres of influence. After the 9/11 attacks, U.S. priorities in the region shifted from fighting communism to combating terrorists, many of whom had freely operated in parts of the region. Today, another cornerstone of U.S. policy toward the region is humanitarian aid, notably the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which provides resources to treat HIV/AIDS.

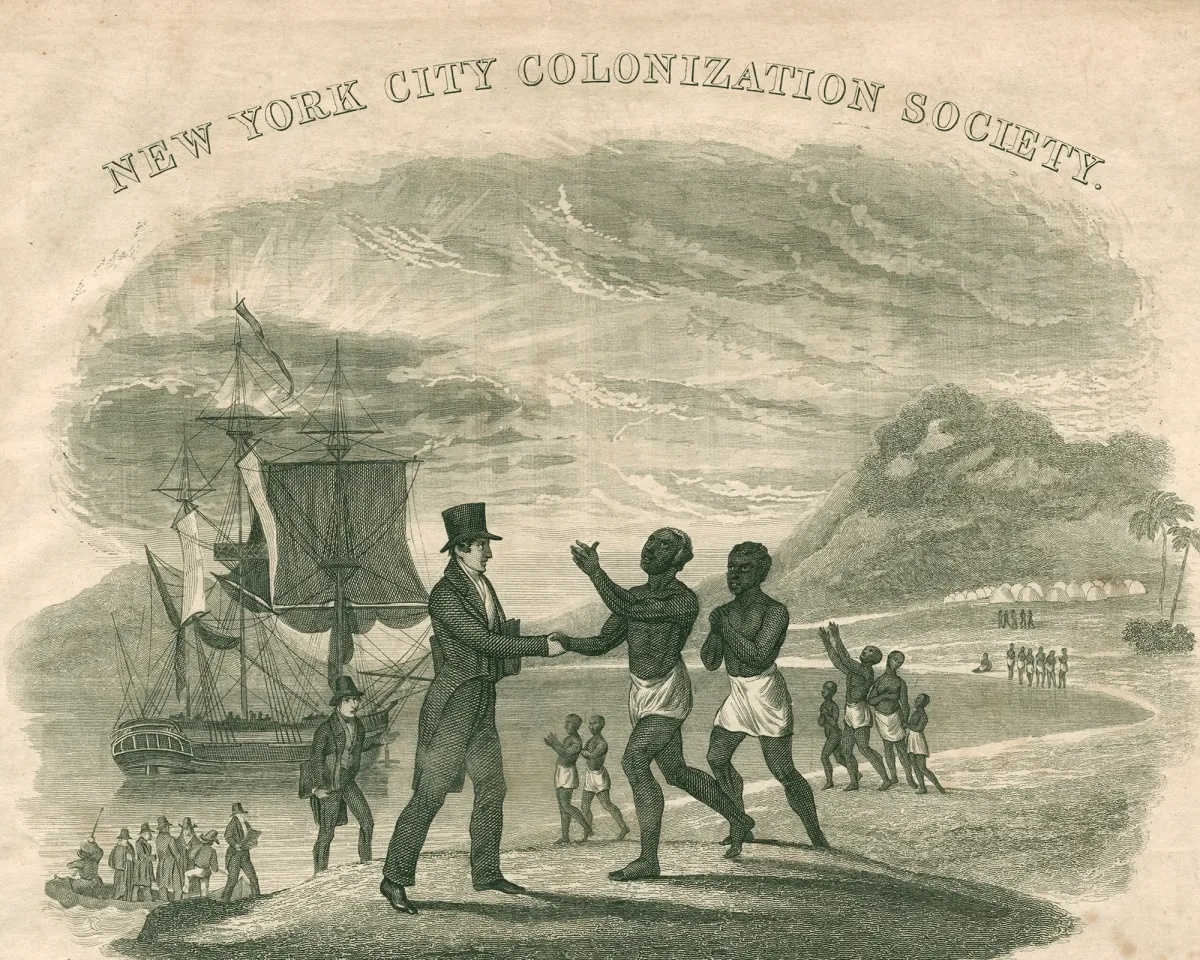

U.S. Leaders Establish African Colony for Freed Slaves

The United States had been linked to sub-Saharan Africa since the colonies began importing African slaves across the Atlantic. As is often the case, domestic and foreign policy overlapped when it came to the issue of slavery. In the early nineteenth century, many white segregationists and some free Black Americans felt that African Americans had no place in the United States, so a group of white Americans (including a few slave owners) founded the American Colonization Society (ACS) in 1817 to establish a colony in West Africa where emancipated slaves could resettle. Some abolitionist leaders like Frederick Douglass protested the plan to remove African Americans from the United States, but in 1821 the ACS founded the colony of Liberia, where fifteen thousand freed slaves settled until around the American Civil War. In 1847, Liberia declared independence with a constitution similar to that of the United States, and the two countries have remained close.

Cold War Rivalries Play Out Across Region

For most of the twentieth century, sub-Saharan Africa ranked low on the list of priorities for U.S. policymakers, but this changed as the Cold War intensified and African nations gained independence. Viewing the region as one more arena to contain Soviet influence, the United States looked to the leaders of Africa’s newly independent countries to join their fight against communism. In particular, the United States feared that communism could have a domino effect in the central and southern parts of the region and this fear led to an era of intervention and proxy wars fought by both the United States and the Soviet Union. In many cases, these Cold War alliances continued after the Soviet threat retreated: eight successive U.S. administrations continued to support the Democratic Republic of Congo’s pro-West leader Mobutu Sese Seko despite the corruption and human rights violations that defined his time in power.

United States Finds Flawed Ally in Apartheid South Africa

South Africa presented a special challenge for U.S. policymakers during the Cold War. On the one hand, the government of South Africa strongly opposed communism. On the other hand, its institutionalized racial segregation, called apartheid, was at odds with the democratic and human rights values that the United States supported. The United States pursued policies that never quite rose to full support for nor full condemnation of the country’s apartheid government. Complicating the relationship further was the fact that South Africa had developed a secret nuclear weapons program. As the Cold War thawed in the 1980s and South Africa began to feel the international isolation caused by apartheid, president F.W. de Klerk took an unprecedented step: he dismantled his country’s nuclear program, the first time in history a country has voluntarily given up its nuclear weapons.

United States Questions Involvement in Africa After Black Hawk Down

After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the United States shifted its priorities in the region from fighting communism to promoting democracy and stability through humanitarian efforts. But intervening in the region’s civil conflicts to provide humanitarian aid turned out to be a complicated and sometimes dangerous endeavor. During a severe food shortage in Somalia in the early 1990s, the United States sent food aid, only to have it stolen by local warlords embroiled in a civil war. The United States deployed its military to support its aid deliveries, but Somali militants shot down two U.S. helicopters on October 3, 1993. Eighteen Americans and more than five hundred Somalis died in what is known as the Battle of Mogadishu or Black Hawk Down. Televised images of Somalis dragging the bodies of U.S. soldiers through the streets of Mogadishu prompted public outcry at home and made subsequent administrations wary of intervening in African conflicts.

Terrorism Draws U.S. Back to Region

After a period of withdrawal from the U.S. military, a series of terrorist attacks refocused U.S. attention back to the region. The first attack occurred in 1998, when the terrorist group al-Qaeda, led by Osama bin Laden, claimed responsibility for two bombings on the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania that left 224 people dead, twelve of whom were Americans. Though occurring on U.S. soil and not in sub-Saharan Africa, the 9/11 attacks resulted in renewed U.S. interest in the region, because groups related to al-Qaeda, like the self-proclaimed Islamic State and al-Shabab, operated freely in the region. To address this threat, the George W. Bush administration created the U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM), which covers all African countries except Egypt. The number of troops on the ground quietly grew under the Trump administration to ninety-six operations active in more than twenty countries. Aiming to limit the influence of Islamist militant groups in the region, the United States trains and supports troops from several countries, and uses private military contractors to combat terrorists operating out of sub-Saharan Africa.

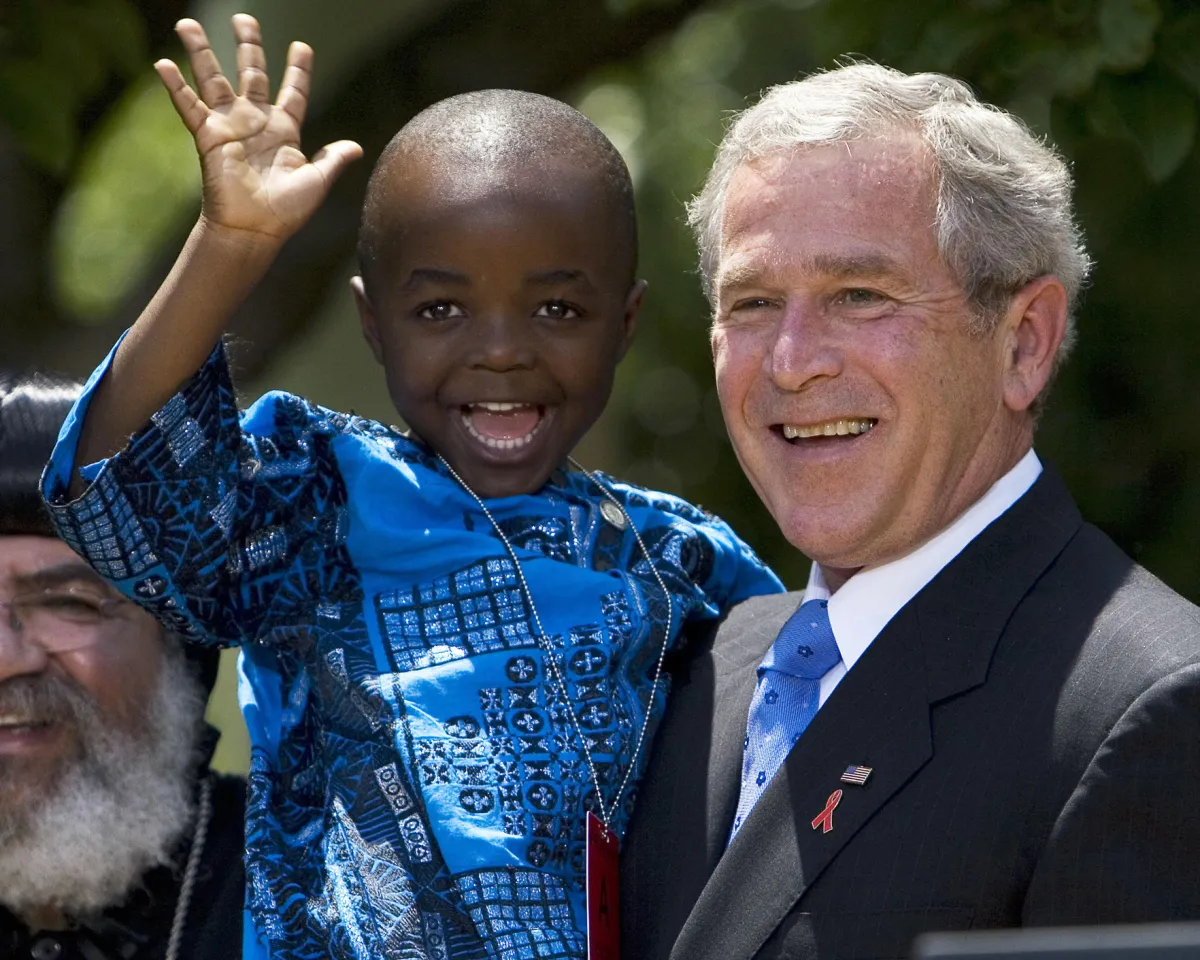

Bush Administration Increases Health Aid

In addition to a new military focus in the region, the George W. Bush Administration brought a renewed interest in global health spending in sub-Saharan Africa, which shoulders most of the world’s health challenges. In 2003, President Bush founded the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), implemented by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), which deploys financial, technical, and material assistance to countries in Africa and around the world. Hailed by many academics and government officials as a success, PEPFAR has provided HIV/AIDS treatment to roughly fourteen million people across the region, saving millions of lives and helping to combat the epidemic. Another independent USAID agency known as the Millennium Challenge Corporation focuses on long-term economic growth, and works with a handful of countries in the region.