Understanding Currencies and Exchange Rates

Supply and demand influence how much a currency is worth. Learn how exchange rates affect producers and consumers.

Have you ever wondered why every country doesn’t just use the same currency? Wouldn’t life be easier if we didn’t have to waste time exchanging bills or calculating conversion in our heads when we travel? Well, the majority of countries have their own currency for a reason, and it’s a simple one: most countries have unique economic situations and want to make monetary decisions based on their specific interests and needs. To understand what those decisions are, it’s important to understand why currencies have different values and how these values shift over time.

Different currencies are worth different amounts.

A Snickers bar might cost you a dollar in the United States, but in Indonesia it could cost you over 14,000 rupiah. Does that mean a chocolate bar is 14,000 times as expensive in Indonesia as it is in the United States? Well, no—if you convert rupiah into U.S. dollars, it actually costs roughly the same.

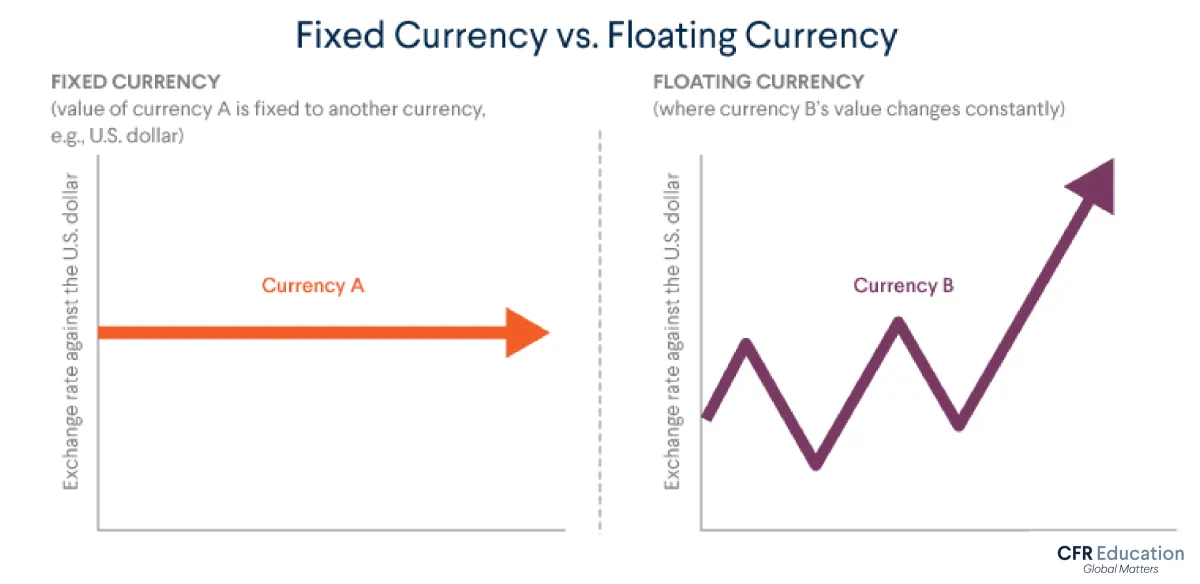

So who decides how much a currency is worth? For a handful of countries, it’s pretty straightforward: these countries pick a commonly used currency, usually the U.S. dollar or the euro, and “peg” their own currency’s exchange rate to this currency. For example, Belize’s central bank decided its currency would be worth one-half of a U.S. dollar. Such currencies are called fixed or pegged. Countries usually peg their currencies to maintain stability for investors, who don’t want to worry about fluctuations in the currency’s value. If a currency’s value drops, for example, the value of the investment would drop as well.

But most exchange rates aren’t fixed—they’re “floating,” meaning their values constantly change depending on various economic factors. As of June 2023, one U.S. dollar is the equivalent of about eighty-two Indian rupees. Twelve years ago, a dollar was worth fifty rupees. And a little over forty years ago, you only needed eight rupees to get one dollar. Over time, the value of the rupee has depreciated, or gone down, making it worth less. Sometimes a currency that depreciates is described as getting weaker because you can buy less foreign currency with it. On the flip side, the Israeli new shekel was worth just nineteen U.S. cents in 2003, but its value has grown over time, trading in for twenty-seven cents in June 2023, a 42 percent increase. Over this time period, the shekel got stronger or more valuable; in other words, the currency appreciated.

Appreciation = getting stronger = worth more = higher value

Depreciation = getting weaker = worth less = lower value

Changes in the value of a currency are influenced by supply and demand.

Currencies are bought and sold, just like other goods are. These transactions mainly take place in foreign exchange markets, marketplaces for trading currencies. Currencies increase in value when lots of people want to buy them (meaning there is high demand for those currencies), and they decrease in value when fewer people want to buy them (i.e., the demand is low). And if a large amount of a currency is lying around in the market (i.e., supply), its value will go down, just like its value would go up if there were not much of it in the market. As you will see below, supply and demand of a currency can change based on several factors, including a country’s attractiveness to investors, commodity prices, and inflation.

A country’s attractiveness to investors can affect what its currency is worth.

Stable countries are considered to be attractive destinations for investments. The more that people want to invest in a country, the more that country’s currency will appreciate or be worth. This is because investors from other countries need to use that country’s currency in order to invest. For example, a French person who wants to invest in the South Korean stock market needs the South Korean won to do so. This demand for won drives up its value.

The opposite is also true: unstable countries do not attract investors. When investors are uncertain about a country’s future, the demand for its currency typically falls. This happened in the United Kingdom after the Brexit referendum in the summer of 2016. Investors didn’t know how the decision to leave the European Union would affect the British economy and were thus unwilling to invest in the country; this led to the devaluation of the British pound sterling.

Another factor that affects demand for a currency is the price of certain commodities, such as oil.

Oil exports make up a large percentage of the Canadian economy. So if a foreign oil company wants to buy oil in Canada, it needs to exchange its foreign currency for Canadian dollars. If oil prices rise, the company will need to exchange more of its currency for Canadian dollars, driving up the demand for the Canadian dollar and thus its value. Similarly, falling oil prices mean foreign oil companies need to spend less of their currency to buy the same amount of oil. This reduces the demand for Canadian dollars and pushes its value down.

Inflation can also affect a currency’s value.

Inflation means higher prices and generally lower purchasing power for a country’s currency. If a country experiences inflation, the prices of its exports increase, making them less attractive to foreigners. Inflation can also decrease domestic demand for domestic goods, leading a country’s importers to exchange their currency for foreign ones in order to buy cheaper goods from abroad. These two effects—reduced foreign demand and increased supply in the market—both work to push a currency’s value down.

A little bit of inflation—say, prices rising by 1 or 2 percent per year—is normal and the sign of a healthy economy. But hyperinflation, an extreme form of inflation in which prices increase out of control, can drastically weaken a country’s currency. Between 2008 and 2009, Zimbabwe experienced hyperinflation after the government overprinted money, in large part to pay off the massive debt that it had accumulated trying to stave off a domestic food shortage. This led to soaring prices and inflation rates of over 100 billion percent.

There are winners and losers when the value of a currency changes.

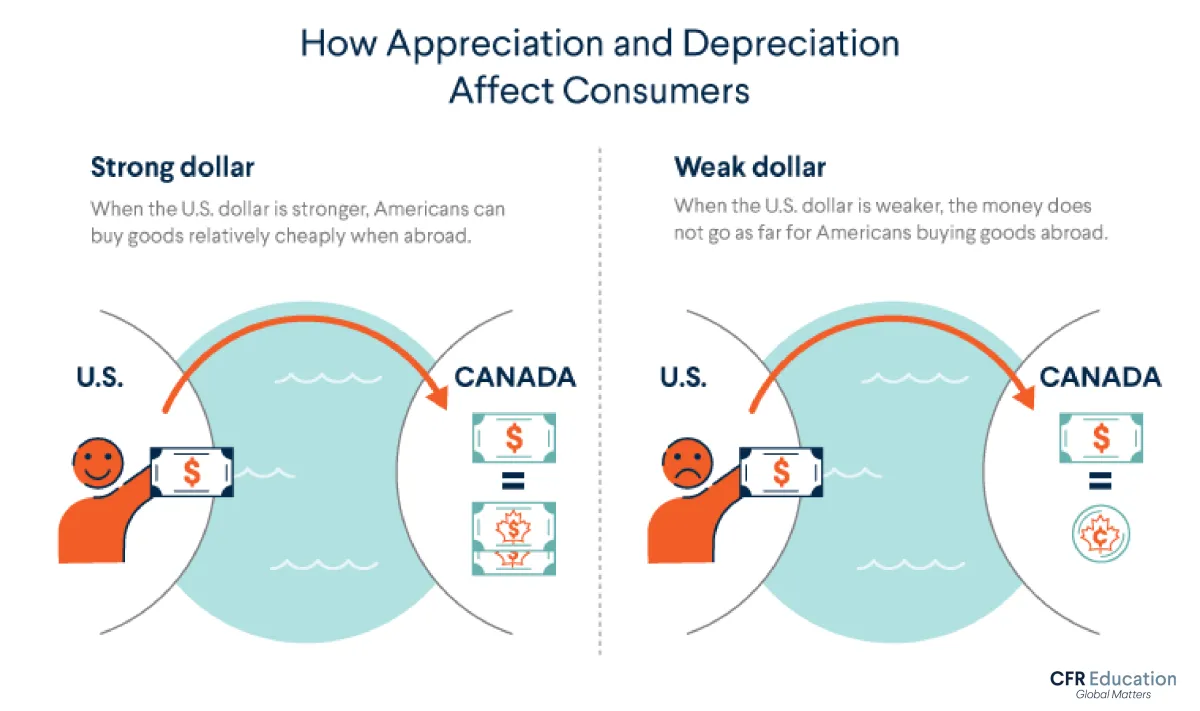

It’s a give-and-take between producers and consumers. If you’re a producer, you want people to buy your goods, so a cheaper currency that makes your goods more attractive abroad is beneficial. But if you’re a consumer who wants to get the most bang for your buck, it’s better for your currency to be strong. (U.S. residents traveling abroad also win with a stronger dollar.)

For some countries, it’s important that a specific group wins. For example, Japan’s economy thrives on exports, so a weaker currency benefits it by making its goods cheaper for consumers abroad. Most Americans like buying cheap goods. Having a strong dollar makes foreign goods less expensive.

Most of the time, market forces like consumer demand determine the value of a currency. But there are exceptions.

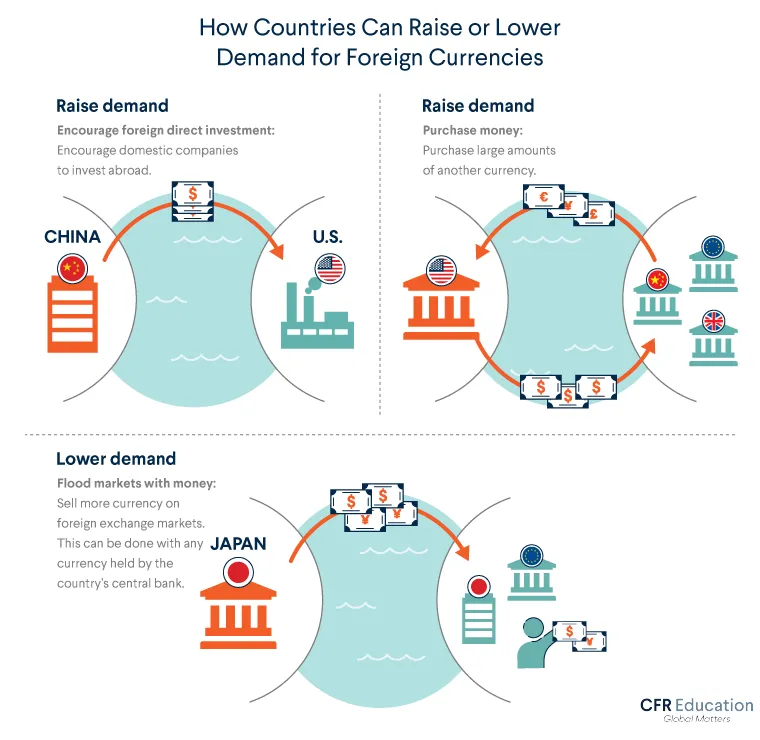

Some countries have been accused of manipulating their currencies, usually to make them weaker so their exports seem cheaper and their manufacturers benefit. How do they do this?

It all goes back to affecting currency supply and demand. Here are some tactics:

- Countries can encourage domestic companies to make foreign direct investment. Foreign investment in a country raises the demand for that country’s currency, as investors need the domestic currency to hire workers and build infrastructure in that country or to make cash investments there.

- Countries can also purchase large amounts of another country’s money. For example, countries can buy U.S. Treasury securities, which are U.S. government debt. These countries need U.S. dollars to buy those securities. As more countries seek to buy U.S. Treasury securities, the demand for the U.S. dollar goes up (in turn reducing the supply of the currency in the market and raising the value of U.S. dollars).

- Countries can flood foreign exchange markets with their own currency (or currencies their central banks hold), reducing the demand for the currency and making it worth less.

So, what would a world with one currency look like?

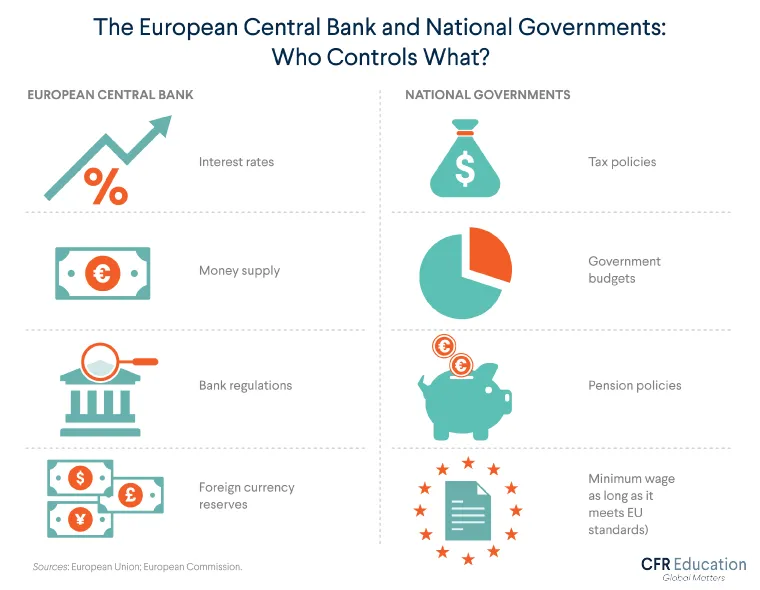

Most countries have their own currency, but there are some exceptions. Most notably, the euro is a currency shared by twenty European countries. Having a shared currency makes it easier for citizens of the eurozone, the area that makes up these twenty countries, to travel and invest across borders and compare prices without having to convert numbers. This helps everyone. For small European countries, a single currency boosts investment; for big European countries, it creates easily accessible markets. Over 340 million people use the currency every day.

But those benefits come with challenges. Eurozone countries hand over control of their monetary policy to the European Central Bank, which is made up of representatives from each country. That means member countries can’t react to their unique economic conditions, such as differences in labor productivity. The success of the eurozone also requires a lot of trust: member countries need to feel confident that the European Central Bank will make decisions that benefit each of them. Similarly, if one member country faces an economic crisis, as Greece did in 2009, its effects will spread to the rest of the eurozone.

Because of these risks, it is unlikely that a common currency like the euro will be replicated elsewhere. For now, most of us who want to travel abroad or invest in other countries will be exchanging money—and paying attention to the changing values of currency.