What Are Market-Based Solutions for Mitigating Climate Change?

Learn how policymakers can design incentives to motivate climate action.

For decades, scientists have argued that the world needs to transition away from planet-warming fossil fuels toward cleaner sources of energy like solar. And for decades, scientists have known how to generate electricity from the sun’s rays.

So why has solar power only really taken off in the past fifteen years?

The full story is complex, but one of the biggest factors has been simple dollars and cents. For a long time, solar power was enormously expensive to produce. However, in recent years, engineering and manufacturing breakthroughs have dramatically reduced the price. Unsurprisingly, as prices fell, more and more people began adopting this increasingly cheap source of energy. For context, solar went from being nearly triple the cost of an equivalent coal plant to just a third of the price between 2009 and 2019.

Governments, businesses, and individuals will often make decisions that are best for their bottom lines. As such, governments with goals like reducing heat-trapping pollution can design policies that make clean sources of energy more affordable than historically cheaper fossil fuels.

This learning resource breaks down three such market-based solutions in the policymaker’s toolkit: taxes, subsidies, and cap-and-trade schemes.

How taxes can help stop climate change

Policymakers can raise the price of fossil fuels to make clean energy more financially appealing. In other words, governments can tax oil, natural gas, and coal.

Governments use taxes all the time—not just to collect revenue but also to influence individual decision-making. For example, lawmakers place taxes on products like alcohol, tobacco, and sugary soda. The taxes increase the price of the products, so people consume less of them. That generates tax revenue for the government and decreases the social and health costs the product causes. For example, if people drink less alcohol, because it is taxed, they themselves are healthier and less likely to make poor decisions that harm other people.

A similar effort could be applied to curb greenhouse gas emissions through what’s known as a carbon tax. Policymakers justify carbon taxes by arguing that businesses and individuals do not pay enough for the carbon they emit. Factory owners, for instance, pay to operate their plants, but they generally do not pay for the expensive climate consequences of blasting tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. A carbon tax would have a factory owner pay for the full societal cost of those operations. The added cost would likely be passed on to the consumer.

Under that model, companies would pay a certain amount in taxes for every ton of carbon dioxide emitted. That figure is also known as the social cost of carbon (SCC). Such an arrangement creates a strong financial incentive for companies and individuals to switch to electric vehicles, renewable energy, and other low-carbon technologies to avoid paying the higher costs from the carbon tax.

The idea might sound straightforward in practice but determining the proper amount for such a tax can prove challenging—and highly political. You can easily imagine how a climate-conscious politician would argue for a higher SCC, whereas an industry-friendly politician might push for a lower SCC.

Carbon taxes have upsides and downsides. Let’s start by exploring some of the benefits: Economists argue that carbon taxes are the most efficient way to encourage companies to reduce their emissions. If policymakers can determine the proper SCC, then they would be taxing businesses at the exact cost they impose on society. Taxes also raise revenue for governments that they can return to the public, spend on climate action, or use for other national priorities.

However, critics of carbon taxes point to the following issues:

- Price-setting challenges: Scientists and economists often disagree over the proper level of the SCC. If set too high, carbon taxes risk suppressing economic growth and productivity. If set too low, carbon taxes can be ineffective in dissuading carbon emissions.

- No emissions cap: If a policymaker’s top priority is to cap carbon dioxide emissions at a certain maximum level, then a carbon tax may not be the best option. That’s because businesses are free to continue emitting as much as they want, so long as they accept the added costs.

- Cost burdens: Consumers generally do not like large price increases, particularly when it comes to gasoline. So, a carbon tax high enough to be effective could risk being pretty unpopular among the public. Also, experts are concerned [PDF] that a carbon tax would be regressive, creating a larger burden for poorer people than for rich people.

To date, thirty-nine countries and subnational entities (states, provinces, or cities) have implemented carbon taxes. Those countries, including Argentina, Canada, France, and South Africa, account for more than 5 percent of the world’s emissions.

In the United States, however, carbon taxes have long remained elusive. Recent presidential administrations have differed widely over SCC figures. President Barack Obama’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) set the SCC around $50 per ton of carbon dioxide. President Donald Trump knocked that figure down to between $1 and $7, arguing that the EPA should focus on damages solely within the United States, not around the world, and that the agency should place less weight on harm to future generations. The Joe Biden administration disagreed with that argument and later raised the SCC to $190, following new scientific analysis and updated guidance from the National Academy of Sciences.

Although the United States does not have a true carbon tax, it has introduced a similar policy in recent years. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act provided the authority to create the nation’s first tax on methane. Methane is a super-potent greenhouse gas with up to eighty times the planet-warming effects of carbon dioxide during the first couple decades after it is emitted.

How subsidies can reduce emissions

If taxes can be said to penalize undesirable behavior like emitting greenhouse gases, subsidies are their opposite. Subsidies provide financial incentives for desirable behavior. They can include giving businesses and individuals money directly or finding other ways to lower the costs of emissions-reducing actions.

Much like taxes, subsidies have benefits and drawbacks. Some upsides include the following:

- Lower cost burdens: Subsidies make certain emissions-reducing behavior cheaper; therefore, they are perceived as more politically popular than taxing behavior that raises emissions. Even though the economic costs would theoretically be the same, policymakers can feel politically safer using subsidies instead of taxes.

- Boost innovation: Subsidies can provide funding for new industries with innovative ideas that otherwise wouldn’t succeed with private funding alone. Ideally, government funding helps new ventures get off the ground. Eventually, those ventures would be able to operate independently without government support.

But, of course, there are downsides too: subsidies often come in the form of tax breaks. That means they lead to lost revenue that governments could have otherwise spent on any number of national priorities. Subsidies also risk promoting less-worthy technology or behaviors while inadvertently stifling more innovative efforts. Government officials won’t make a perfect decision about which technology to support every time.

The Inflation Reduction Act offered hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies to companies that took climate-friendly actions. Such actions included producing renewable energy, deploying battery storage technologies, and installing carbon capture [PDF] and storage systems. The landmark legislation marked the United States’ largest-ever investment in addressing climate change. The act pledged around $370 billion over the course of ten years.

The United States is by no means alone in taking those kinds of steps. Germany’s Energiewende (energy transformation) is a government-funded initiative to transition the economy away from nuclear and fossil-fuel energy to renewable sources. The initiative uses a combination of regulation, carbon pricing, and subsidies to renewable power. China, too, is a global leader in subsidies. It offers hundreds of millions of dollars in assistance to renewable energy production each year. Such government support has led to world-leading capacity in solar panel and electric vehicle production.

Clean energy is not alone in benefiting from subsidies. In 2022, governments around the world subsidized fossil fuels to the tune of $7 trillion. Experts argue that climate progress can be achieved by rolling back such subsidies. Analysts at the International Monetary Fund estimate that eliminating global fossil-fuel subsidies altogether “would prevent 1.6 million premature deaths annually, raise government revenues by $4.4 trillion, and put emissions on track toward reaching global warming targets.”

How cap-and-trade systems work

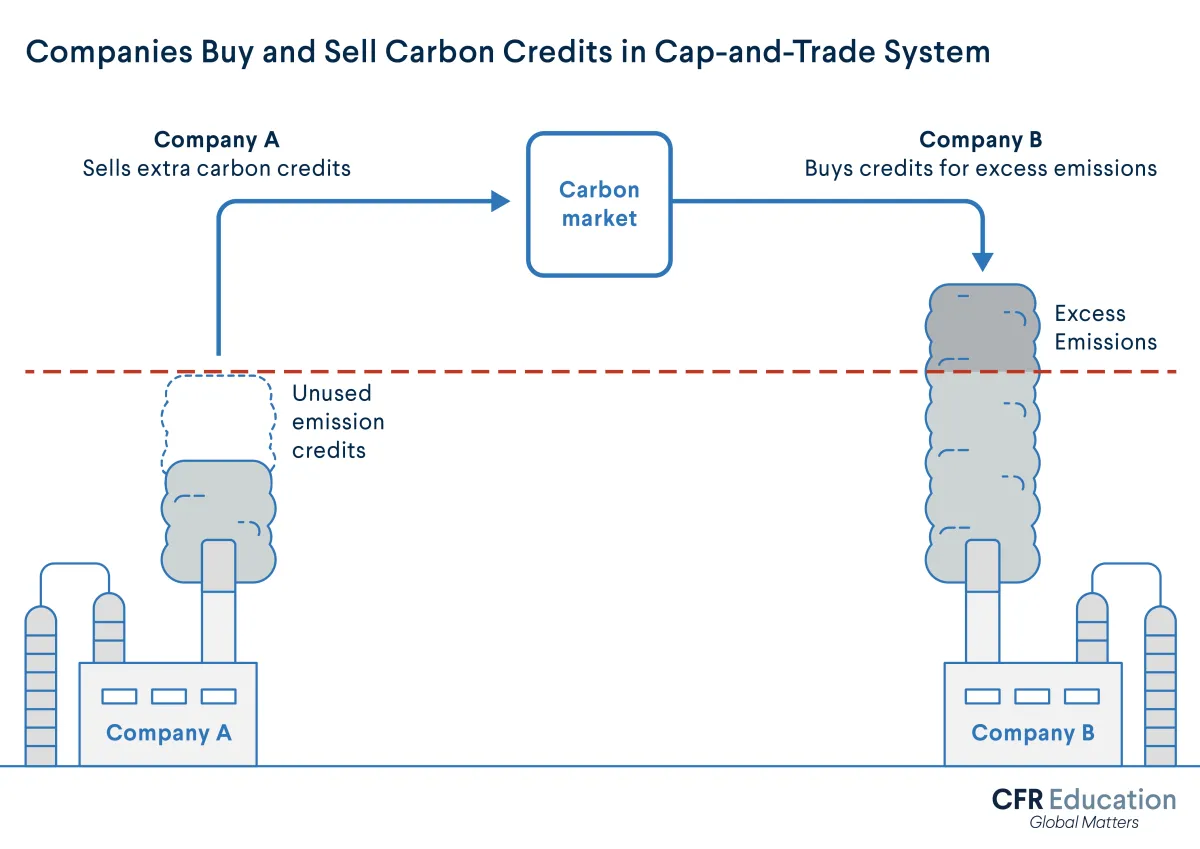

Under cap-and-trade systems, governments determine a maximum level (cap) for carbon emissions. Companies are then given credits that cover the amount of carbon they are allowed to emit each year. If companies emit less than their allotted total, or if they receive extra credits by removing carbon from the atmosphere, they can sell (trade) their excess credits to other companies in a carbon market for extra profit. If they emit more, they have to buy credits, creating a financial penalty for emitting.

Many cap-and-trade schemes are designed to reduce the number of carbon credits in circulation over time. That drives down economy-wide emissions without imposing specific limits on any individual company or industry.

The main benefit of cap and trade is quantity certainty. Cap-and-trade systems allow policymakers to place a firm ceiling on carbon dioxide emissions, making for an effective policy when a government has a clear emissions target.

Meanwhile, downsides include price uncertainty and logistical challenges. Although cap-and-trade systems provide more certainty on the quantity of emissions, the potential price of the credits is less clear. If demand for emissions-producing activities is higher than expected, the prices for credits and costs for producers and consumers will increase by more than expected. Furthermore, establishing carbon markets to trade and monitor carbon credits can prove challenging. Without proper enforcement—which, itself, can be highly expensive—fraud can run rampant in under-regulated carbon markets.

Today, scores of countries, states, provinces, and cities have functional carbon markets. Those markets cover around a quarter of the world’s emissions. In the United States, ten states participate in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, a cap-and-trade program for the power sector.

Ultimately, market-based policies are meant to change people’s decision-making to incorporate the external costs and benefits of their actions. When individuals or businesses emit greenhouse gases, they create an external cost for society in the form of climate change. So, increasing the cost of that behavior via taxes and cap-and-trade systems should make them less likely to decide on those harmful actions.

Conversely, when individuals or businesses decide to reduce their emissions, they create an external benefit for society by reducing climate change. Increasing the benefits (or lowering the costs) of those actions with subsidies can make people more likely to take those beneficial actions.

And those market-based solutions are not mutually exclusive. Policymakers can use all three—taxes, subsidies, and cap-and-trade systems—to lower emissions and help stop climate change.