Daylight Saving Time

Senate Sergeant at Arms Charles Higgins turns forward the Ohio Clock for the first Daylight Saving Time, while Senators William Calder (NY), William Saulsbury, Jr. (DE), and Joseph T. Robinson (AR) look on in the Capitol building in Washington, D.C. in 1918.

Source: Library of Congress

Developed during World War I to conserve energy and free up more daylight hours for battle, daylight saving time (DST) was meant to be a temporary fix, though essays dating back decades argued for its implementation; in 1794, Benjamin Franklin made the case in financial (candle cost-savings), productivity (longer workdays), and moral (a remedy for laziness) terms. Although most of the world repealed DST when the first World War ended, World War II led to its quick re-adoption and popularization as a long-term solution. The year-round DST we observe in the United States was introduced in the winter of 1973 amidst a global energy crisis.

Vegetarian Sausage

Women serve food from a mobile lunch kitchen in Berlin in 1916 during World War I. The sign reads: “Warm lunch. Supplied by the Association of the Berlin People’s Kitchen 1866.”

Source: Library of Congress

Before World War I, these modern grocery store staples didn’t exist. Created in sausage-loving Germany during the war as a cheap way to add protein to meals amidst frequent food shortages, vegetarian sausages were the brainchild of Cologne’s then-mayor Konrad Adenauer. His Kölner Wurst or “Cologne sausage” used soya, flour, corn, barley, and ground rice and were infamously bland. The meat substitutes available today have made big gains in texture and taste but rely on many of the same ingredients from Adenauer’s original recipe.

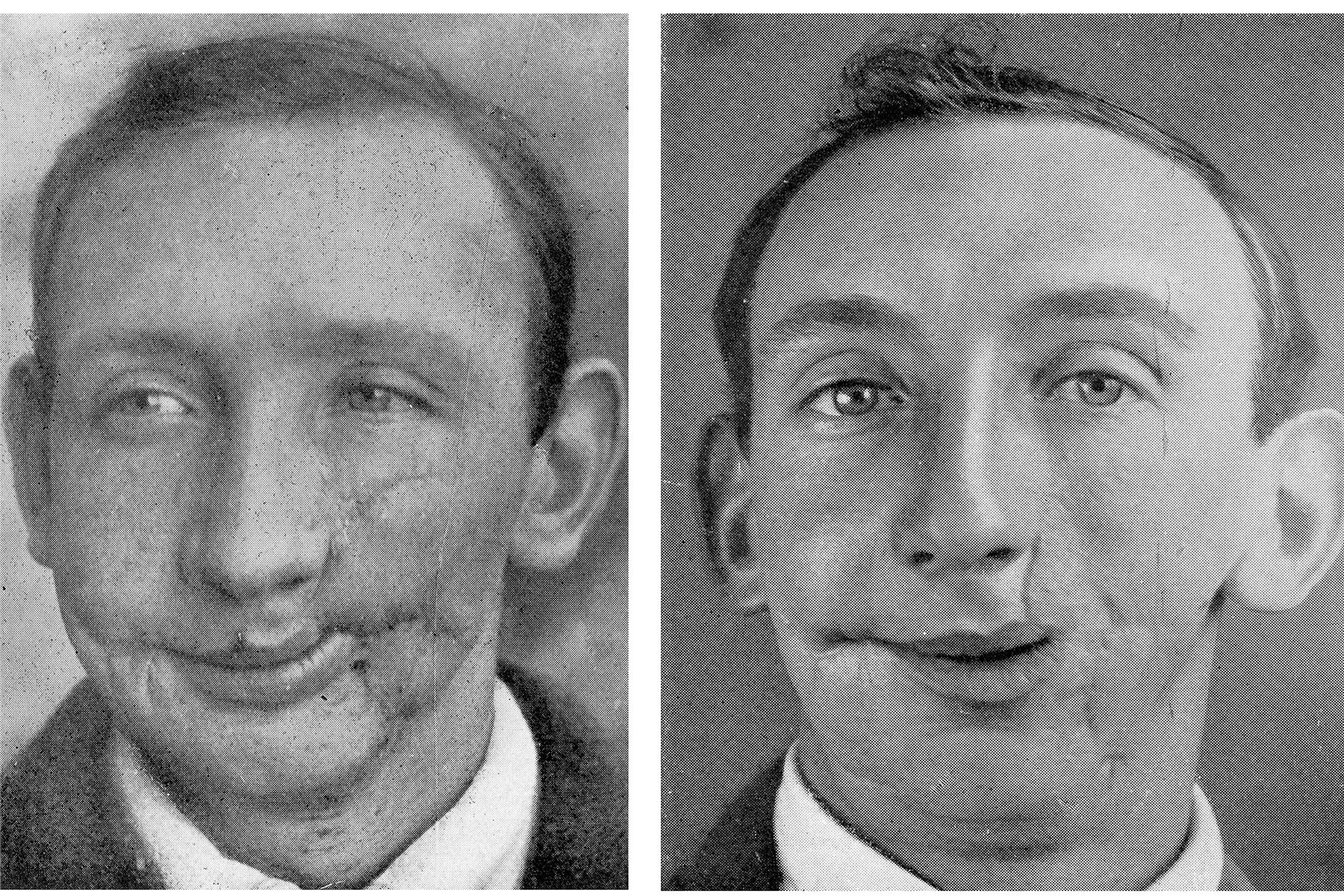

Plastic Surgery

Photographs document the facial reconstruction of a soldier whose cheek was extensively wounded during the Battle of the Somme.

Source: Science & Society Picture Library via Getty Images

Before World War I, people who experienced disfiguring wounds had limited options to choose from. However, as the number and magnitude of facial disfigurations skyrocketed among soldiers fighting in the First World War, the medical community worked quickly to invent reconstruction procedures. Dr. Harold Gillies is credited with the idea to use patients’ own facial tissue to decrease the chance of transplant rejection, leading to rapid innovation in the field of plastic surgery capabilities spanning from successful skin grafts to the first sex reassignment surgeries.

Everyday Words and Phrases

A close-up of a 1945 Webster dictionary.

Source: Benoit Daoust/Shutterstock.

Next time you “ace” a test, unexpected news leaves you “shell shocked,” or that highly anticipated movie turns out to be a “dud,” you’re using language directly handed down from wartime. From World War I, English gained words like “lousy,” which transformed from an adjective to describe lice infestations to mean weary, and “trench coat,” which transitioned from battlefield necessity to universal fashion statement. World War II added household brands Spam (a mashup of “spiced” and “ham”) and Jeep (from the initials GP, which described its wartime roots as a general purpose vehicle). The global entanglement also created a melting pot of cultural ideas and terms. For example, describing something comfortable or privileged as “cushy,” is a direct contribution to the English language from Indian troops who fought alongside the British in World War I.

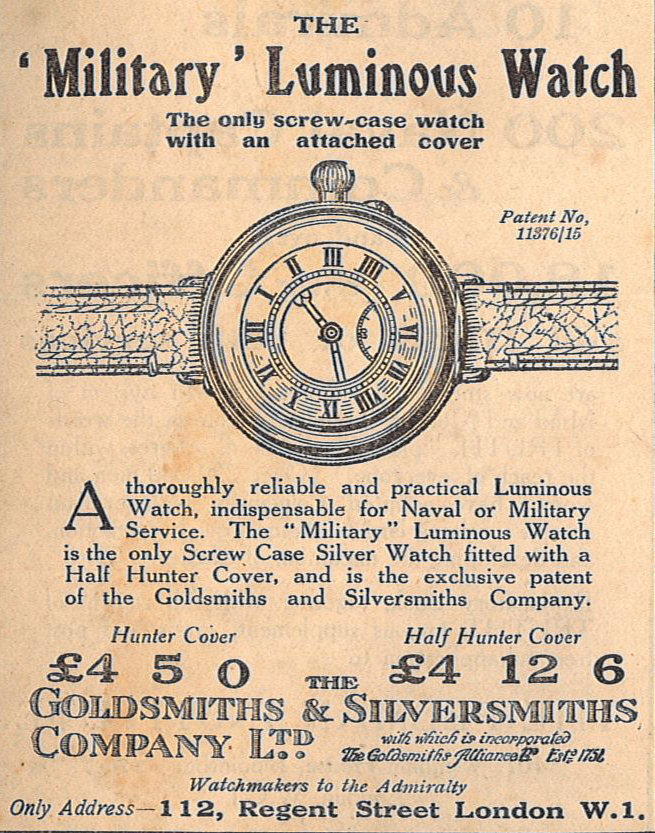

Wristwatches

An advertisement from 1918 for a wristwatch.

Source: Signalling by Capt. E.J. Solano (1918)

Before we could check the time with the phones in our pockets, most people had to dig out their pocket watch to accomplish this essential task. That proved to be quite inconvenient for soldiers in the trenches, who were also operating without church bells and factory whistles to orient themselves in time. Wristwatches, the obvious solution to this problem, were seen as feminine accessories before World War I, a perception that changed rapidly as they became a crucial part of soldiers’ gear. The phrase “synchronize your watches” came to symbolize their importance on the battlefield where fighting had to be precisely scheduled and timing was a vital tool for communication and survival.

Newsreels

A group of cameramen filming an event in June 1916.

Source: Topical Press Agency via Getty Images

The advent of the twenty-four-hour news cycle stems from one of the earliest forms of broadcast: newsreels. Without televisions, cell phones, or social media, people would line up at movie theaters to watch hour-long loops of news and entertainment features. Early video cameras were bulky, so newsreels rarely included war reporting at the start of World War I, instead covering parades, sports events, and cultural moments like royal weddings. Yet as the war progressed and the public hungered for updates, newsreels began to include footage from the conflict, including unprecedented imagery for the time—the launch of military ships, civilians fleeing their villages, prisoners of war, cratered battlefields—that led to a new awareness about wartime destruction.