Iraq’s Invasion of Kuwait

Hundreds of displaced refugees fleeing Kuwait stand in long lines for food and water from relief workers on the Iraqi-Jordanian border on September 1, 1990, shortly after the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq.

Source: Peter Turnley/Corbis via Getty Images

What happened: In August 1990, Iraq—in steep debt and seeking to add Kuwait’s substantial oil reserves to its ledger—invaded Kuwait after accusing it of overproducing and stealing oil. Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein went on to annex Kuwait, as the country’s emir fled.

Click the down button or swipe up to see how the world responded.

Iraqi soldiers surrender to the Allied forces in Kuwait during the Persian Gulf War on February 24, 1991.

Source: Jacques Langevin/Sygma via Getty Images.

The response: On August 8, 1990, then U.S. President George H.W. Bush said in a televised address: “The acquisition of territory by force is unacceptable.” The UN Security Council imposed sanctions against Iraq and later gave the country a deadline of January 15, 1991, to withdraw from Kuwait, which Saddam ignored. A U.S.-led coalition commenced a UN-approved air and ground campaign against Iraqi forces. At the end of February 1991, Bush announced that Kuwait had been “liberated.” In this case, a clear violation of sovereignty was met with a UN-backed international military response.

Killing of Osama Bin Laden

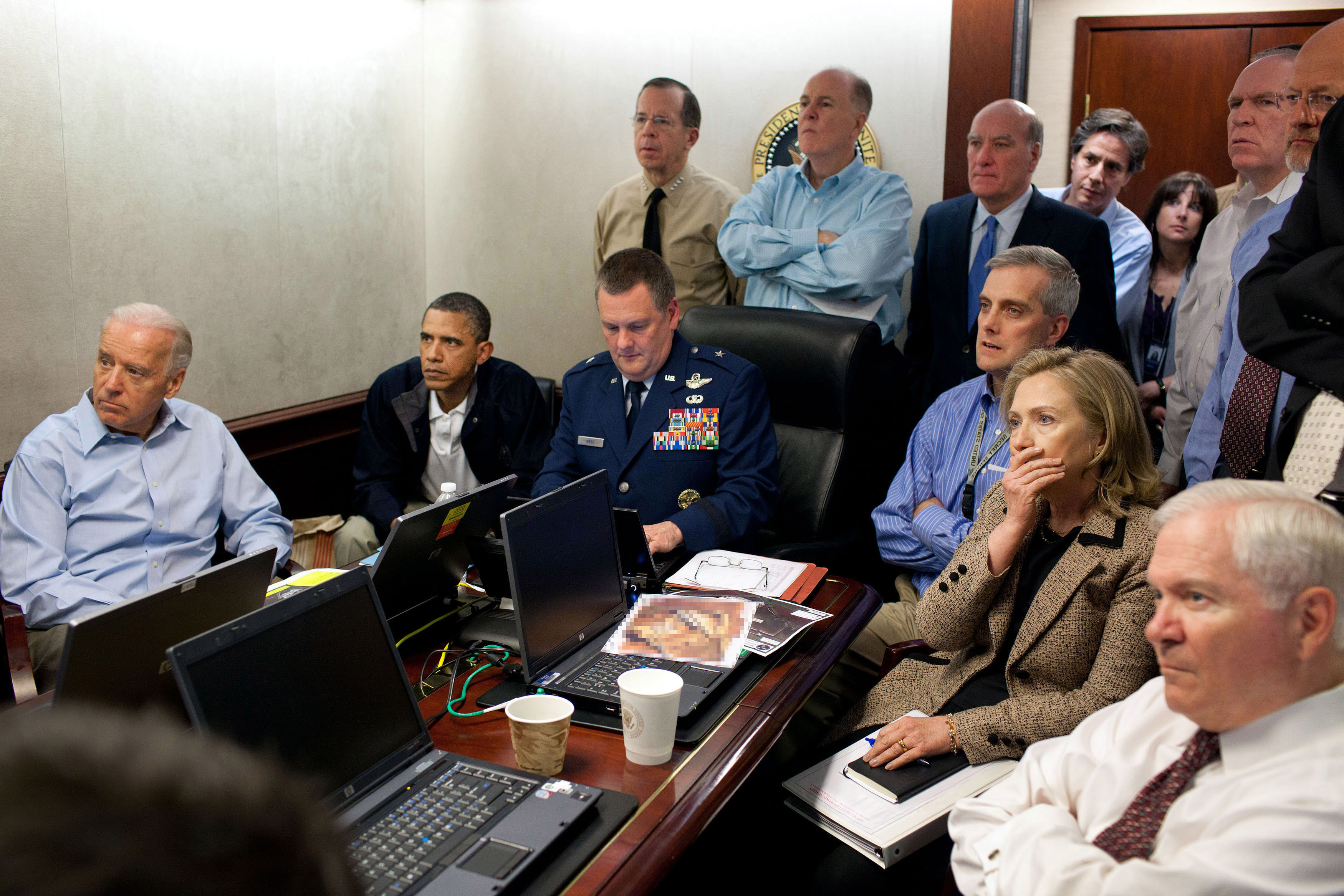

U.S. President Barack Obama (second left) and Vice President Joe Biden (left), along with members of the national security team, receive an update on the mission against Osama bin Laden in the Situation Room of the White House on May 1, 2011.

Source: Pete Souza/White House via Reuters

What happened: The United States’ global war on terror began in the aftermath of the devastating attacks of September 11, 2001. Soon thereafter, Congress passed a wide-ranging resolution that authorized military force against anyone involved in the attacks. For years, Osama Bin Laden—the leader of al-Qaeda, the terrorist group that executed the attack—remained hidden. But in May 2011, a team of U.S. Navy SEALs raided a compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, and killed Bin Laden.

Click the down button or swipe up to see how the world responded.

Pakistani protesters shout anti-US slogans during a protest on the third anniversary of the death of slain Al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, in Multan on May 2, 2014.

Source: Shahid Saeed Mirza/AFP via Getty Images

The response: Pakistan’s foreign ministry labeled the raid “an unauthorized unilateral action” and warned countries against taking similar steps. Its army issued a statement saying future actions infringing on Pakistan’s sovereignty would cause the country to reconsider its cooperation with the United States. While the Pakistani Foreign Secretary Salman Bashir questioned the legality of the move, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder argued the killing was in “national self-defense” and lawful. Instead of countering with military force or sanctions, the Pakistani government kept its response in the realm of politics and diplomacy.

Annexation of Crimea

Soldiers, believed to be Russian, ride on military armoured personnel carriers on a road near the Crimean port city of Sevastopol on March 10, 2014.

Source: Baz Ratner/Reuters

What happened: As Ukraine forged closer ties to the European Union and experienced democratic protests in February 2014, Russian troops invaded Crimea, a region in Ukraine with historic ties to Russia. Russia formally annexed Crimea after the territory voted in a disputed referendum to join Russia. Western powers called the process illegal.

Click the down button or swipe up to see how the world responded.

A wide view of the Security Council during its vote on a draft resolution that declared the planned referendum on independence for Ukraine's Crimea region illegal and urged countries not to recognise the results on March 15, 2014.

Source: Eskinder Debebe/United Nations

The response: In March 2014, the UN General Assembly voted overwhelmingly to nullify the validity of the Crimea referendum. The European Union and the United States announced economic and political sanctions against Russia for what was viewed as a clear violation of Ukrainian sovereignty. While the United States has armed the Ukrainian military, it has refrained from a direct military intervention. Russia has not withdrawn from Crimea, and more than ten thousand people have died in the ongoing conflict between Russian-backed separatist forces and the Ukrainian military.

2016 U.S. Presidential Election

Former Acting Attorney General Sally Yates, along with former Director of National Intelligence James Clapper, testifies about potential Russian interference in the presidential election before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., on May 8, 2017.

Source: Aaron P. Bernstein/Reuters

What happened: In the run-up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, John Podesta, campaign chair for the Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton, clicked on an email asking him to reset his password. What Podesta didn’t know was that the email was part of a coordinated, Russia-backed cyber campaign meant to interfere with the 2016 election. Hackers used Podesta’s credentials to gain access to the Democratic National Committee networks, leak emails, and spread disinformation across the internet in support of the Republican nominee Donald J. Trump.

Click the down button or swipe up to see how the world responded.

U.S. President Barack Obama participates in his last news conference of the year at the White House in Washington, D.C., on December 16, 2016. Obama said he had confronted Russian leader Vladimir Putin in person over allegations of Russian hacking when they met ahead of the U.S. election.

Source: Carlos Barria/Reuters

The response: While still in office in 2016, then President Barack Obama threw nearly three dozen Russian intelligence agents out of the United States and announced sanctions against several people and entities, including two Russian intelligence groups. Sanctions for election interference have continued under the Trump administration, with new restrictions added in September 2018 over attempted meddling in that year’s midterm elections. Though international laws on cyberspace behavior are sparse, interference in another country’s elections can be considered a threat to sovereignty.

North Korea WannaCry Cyberattack

Tom Bossert, homeland security adviser to President Donald Trump, and Jeanette Manfra, assistant secretary at Homeland Security's Office of Cybersecurity and Communications, arrive to hold a briefing where they blamed North Korea for unleashing the so-called WannaCry cyber attack at the White House in Washington, D.C., on December 19, 2017.

Source: Kevin Lamarque/Reuters

What happened: In 2017, a malicious piece of software called WannaCry infected hundreds of thousands of computers worldwide, locking governments, hospitals, and big companies such as FedEx and Renault out of information on their machines and holding it for ransom. The cyberattack, which was attributed to North Korea, hit Britain particularly hard, costing the country’s health-care provider, the National Health Service (NHS), tens of millions of dollars.

Click the down button or swipe up to see how the world responded.

First Assistant U.S. Attorney Tracy Wilkison announces charges against a North Korean national in a range of cyberattacks on September 6, 2018 in Los Angeles, California.

Source: Mario Tama/Getty Images

The response: In 2018, the U.S. Department of Justice announced criminal charges against an alleged member of the North Korean–backed hacking group accused of creating the ransomware. Park Jin-hyok and the Lazarus Group were also targeted with sanctions. Meanwhile, Britain declared that it had the capacity to carry out a retaliatory cyberattack but said that doing so would risk tit-for-tat escalation. Experts have argued that the attack violated sovereignty as it caused damage and interfered with a system under the British government’s authority.